Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

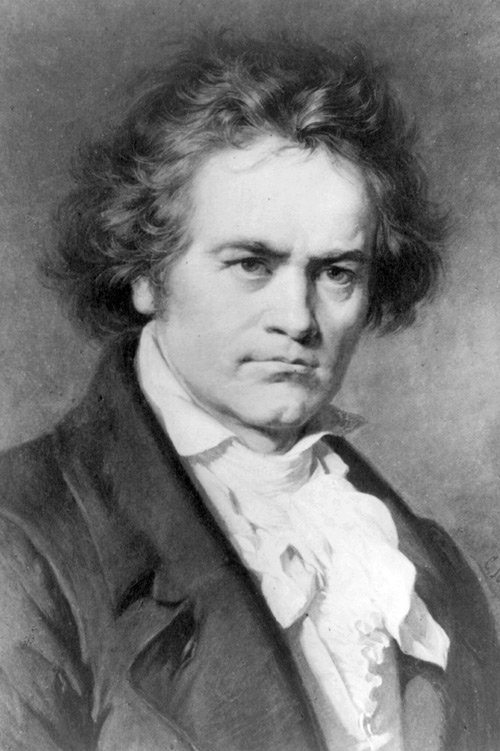

This Week in Classical Music: December 11, 2023. Beethoven and Berlioz. On December 16th we’ll celebrate Ludwig van Beethoven’s 253rd anniversary. As we thought of it, we remembered what happened on this date three years ago when the world was supposed to celebrate a monumental date, Beethoven’s 250th. It didn’t happen, as our musical organizations couldn’t bring themselves to honor a white male composer – that was the year of Critical Race Theory run amok, DEI ruling the world, and sanity running for cover On the website Music Theory’s White Racial Frace, Philip Ewell, a black musicologist, published an article titled “Beethoven Was an Above Average Composer – Let’s Leave It at That” which contained a sentence: “But Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is no more a masterwork than Esperanza Spalding’s 12 Little Spells.” Alex Ross, our most important public music critic, felt compelled to respond to this nonsense with an article of his own, publishing “Black Scholars Confront White Supremacy in Classical Music” in the New Yorker magazine. The article's subtitle was: “The field must acknowledge a history of systemic racism while also giving new weight to Black composers, musicians, and listeners.” In the New York Times, Anthony Tomassini, the chief classical music critic who is no longer with the newspaper, wrote an article about the harm of the blind, behind-the-curtain orchestral auditions. Those were widely accepted a quarter century ago to avoid any racial or gender biases, but Tomassini argued that it hinders the racial diversification of our orchestras: “The audition process should take into account race, gender and other factors.” We wonder if he still thinks that way, or was that just intellectual cowardice, an attempt to cover his hide: after all, for decades he was toiling in a field that purportedly turned out to be racist through and through, and in all these years it never occurred to him to assess it in racial terms. All of this was just three years ago. This major burst of insanity seems to be behind us and hopefully will dissipate completely, sooner rather than later. Do we need to add a disclaimer that we are totally against any racial and gender discrimination, whether in music or any other cultural or social sphere? We hope not.

remembered what happened on this date three years ago when the world was supposed to celebrate a monumental date, Beethoven’s 250th. It didn’t happen, as our musical organizations couldn’t bring themselves to honor a white male composer – that was the year of Critical Race Theory run amok, DEI ruling the world, and sanity running for cover On the website Music Theory’s White Racial Frace, Philip Ewell, a black musicologist, published an article titled “Beethoven Was an Above Average Composer – Let’s Leave It at That” which contained a sentence: “But Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is no more a masterwork than Esperanza Spalding’s 12 Little Spells.” Alex Ross, our most important public music critic, felt compelled to respond to this nonsense with an article of his own, publishing “Black Scholars Confront White Supremacy in Classical Music” in the New Yorker magazine. The article's subtitle was: “The field must acknowledge a history of systemic racism while also giving new weight to Black composers, musicians, and listeners.” In the New York Times, Anthony Tomassini, the chief classical music critic who is no longer with the newspaper, wrote an article about the harm of the blind, behind-the-curtain orchestral auditions. Those were widely accepted a quarter century ago to avoid any racial or gender biases, but Tomassini argued that it hinders the racial diversification of our orchestras: “The audition process should take into account race, gender and other factors.” We wonder if he still thinks that way, or was that just intellectual cowardice, an attempt to cover his hide: after all, for decades he was toiling in a field that purportedly turned out to be racist through and through, and in all these years it never occurred to him to assess it in racial terms. All of this was just three years ago. This major burst of insanity seems to be behind us and hopefully will dissipate completely, sooner rather than later. Do we need to add a disclaimer that we are totally against any racial and gender discrimination, whether in music or any other cultural or social sphere? We hope not.

Back to Beethoven. We looked up our library, and it turns out that while we have most of Beethoven’s piano sonatas, we don’t have the sonata no. 19, a short and misnumbered piece, easy enough to be well known to practically all young pianists. Beethoven composed it sometime in 1797, about the same time as his sonatas nos. 3 and 4, but it wasn’t published till 1805 and thus acquired its late opus and number. Here it is, performed by Alfred Brendel in a 1992 recording.

sometime in 1797, about the same time as his sonatas nos. 3 and 4, but it wasn’t published till 1805 and thus acquired its late opus and number. Here it is, performed by Alfred Brendel in a 1992 recording.

Also, on this day 220 years ago Hector Berlioz was born in La Côte-Saint-André, a small town halfway between Lyon and Grenoble. Berlioz was one of the greatest composers France ever produced, and a very unusual one at that: he didn’t follow any established schools and didn’t leave any behind. We’ve written about Berlioz many times, and he requires a separate entry, so for now, here is his symphony cum viola concerto Harold in Italy (parts 1, Harold in the mountains,2, March of the pilgrims, 3, Serenade of an Abruzzo mountaineer, and 4, Orgy of bandits). The great violinist Yehudi Menuhin is playing the viola, with Sir Colin Davis conducting the Philharmonia Orchestra. Permalink

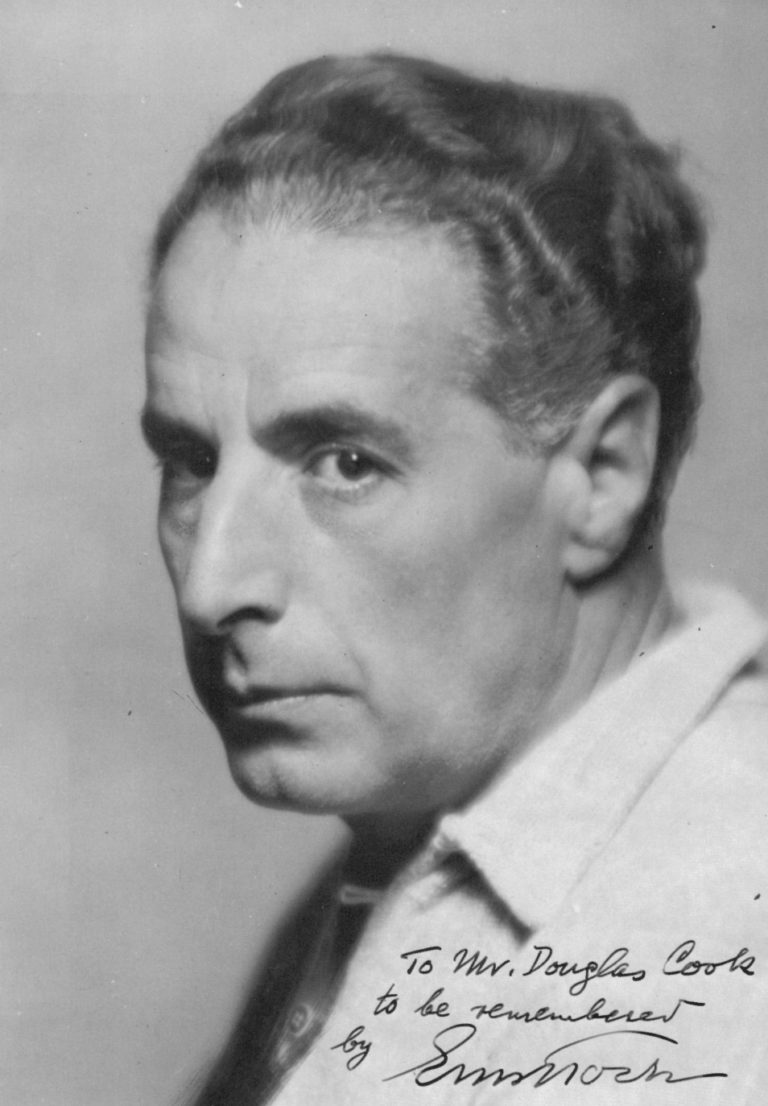

This Week in Classical Music: December 4, 2023. Ernst Toch and more. Erns Toch, the Jewish-Austrian composer, was born on December 7th of 1887 in Leopoldstadt, a poor, mostly Jewish area in Vienna. Toch was one of a group of Austrian and German composers whose lives were upended by the rise of Nazism (Arnold Schoenberg, Franz Schreker, Karl Weigl, Egon Wellesz, Hans Gál, Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Berthold Goldschmidt, all Jewish, mostly forgotten except of course for Schoenberg, all talented if to a different degree, had their lives broken in 1933). One thing we find interesting is the ease with which they moved from Austria to Germany. These were two very different empires, one, declining, ruled by the peace-seeking Emperor Franz Joseph from Vienna, another – very much on the ascent, economically, politically and militarily, ruled by the arrogant and insecure Keiser Wilhelm II. But musicians thought nothing of moving from one country to another, from Vienna to Berlin and back, conducting in Hamburg or Leipzig one year and then returning to Austria, teaching at Berlin’s Hochschule für Musik and then at Universität für Musik in Vienna. And they didn’t need permission to work as long as positions were available. Musically, the pre-WWI Austria and Germany were one space, even more so than they are now.

Jewish area in Vienna. Toch was one of a group of Austrian and German composers whose lives were upended by the rise of Nazism (Arnold Schoenberg, Franz Schreker, Karl Weigl, Egon Wellesz, Hans Gál, Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Berthold Goldschmidt, all Jewish, mostly forgotten except of course for Schoenberg, all talented if to a different degree, had their lives broken in 1933). One thing we find interesting is the ease with which they moved from Austria to Germany. These were two very different empires, one, declining, ruled by the peace-seeking Emperor Franz Joseph from Vienna, another – very much on the ascent, economically, politically and militarily, ruled by the arrogant and insecure Keiser Wilhelm II. But musicians thought nothing of moving from one country to another, from Vienna to Berlin and back, conducting in Hamburg or Leipzig one year and then returning to Austria, teaching at Berlin’s Hochschule für Musik and then at Universität für Musik in Vienna. And they didn’t need permission to work as long as positions were available. Musically, the pre-WWI Austria and Germany were one space, even more so than they are now.

Toch was at his most productive in the 1920s, when he wrote the Concerto for Cello and Chamber Orchestra, Bunte Suite, two short operas, many chamber pieces and piano music. Here’s Bunte Suite, whose sophisticated humor reminds us of the music of another Austrian composer, Ernst Krenek. The Suite is performed by the Karajan Academy of the Berliner Philharmoniker, Cornelius Meister conducting. You can read about Toch’s life after Hitler assumed power in last year’s post.

Jean Sibelius was also born this week, on December 8th of 1865. We have to admit that we’re not big fans of the Finnish composer, but his one-movement Symphony no. 7, is a masterpiece. Even though it’s his shortest, about 23 minutes long depending on performance, it took Sibelius 10 years (from 1914 to 1924) to complete. During that time, he managed to complete two more symphonies, nos. 5 and 6. Here’s the Seventh, performed by the Berlin Philharmonic under the direction of Herbert von Karajan.

While Sibelius may not be one of our favorites, Olivier Messiaen, born on December 10th of 1908, clearly is. We’ve written about him on several occasions and will get back to the great French master soon. Also this week: Henryk Górecki, a Polish composer whose minimalist symphonies became very popular with audiences worldwide, born on December 6th of 1933, and César Franck, the composer of one of the best violin sonatas, on December 10th of 1822. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: November 27, 2023. Maria Callas. We’re a bit early, but next Sunday is the 100th anniversary of Maria Callas, La Divina, as she was known worldwide: she was born on December 2nd of 1923. It feels very strange that’s already been a century since her birth, as her presence is felt as strongly today as on the day she died in 1977: her instantly recognizable voice could be heard on classical music radio stations, on streaming services, on YouTube and (still) on CDs. The means have changed – back then it was LPs that people were buying and listening to – but she’s as adored as ever. Her Casta Diva alone has been heard on YouTube about 35 million times. Callas was so closely associated with Italian opera – Bellini, Donizetti, Verdi, Puccini – that she seemed Italian, but in fact was American, of Greek descent. She married an Italian, Giovanni Battista Meneghini, and, while they were married used his name with her own as Maria Meneghini Callas. She moved to Greece in 1940 and studied voice at the Athen Conservatory. There, she sang in the opera for the first time, appearing as Tosca in 1942. She returned to the US in 1945 but soon left for Italy. Tulio Serafin, the famous conductor who coached generations of singers, became her mentor. In 1947, at the Arena of Verona, he conducted Callas in her first Italian role, as La Gioconda in Ponchielli’s eponymous opera. Her appearance was tremendously successful and brought her career to a different level. During that time she often sang in the rarely produced bel canto operas, mostly because she was the only one who could sing these very difficult roles. She was exceptional as Donizetti’s Anna Boleyn, as Imogene and Norma in Bellini’s Il Pirata and Norma, Lucia in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, Lady Macbeth and Violetta in Verdi's Macbeth and Traviata, and, of course, as Tosca. For three years she sang in smaller theaters, then, in 1950, she appeared, as Aida in La Scala. Even though her relationship with the management was troubled, in the 1950s La Scala became Callas’s home. Neither did Callas have a rapport with Rudolph Bing, the manager of the Met, where she premiered only in 1956. She had a reputation as a temperamental diva, but many of her colleagues thought that it was her exactness that made her difficult to work with. Later in the 1950s, she started experiencing problems with her voice, which may have contributed to her sometimes-erratic behavior. Some think that it was the loss of weight that affected her voice; in the early 1950s Callas was rather heavy, but then went on a diet and lost about 80 pounds. By the late 1950s, her vibrato was too heavy, sometimes the voice was forced and one could hear pronounced harshness, even though other performances were still excellent. Overall, Callas sang at the top of her form for just 10 years but what glorious years they were! Even her detractors, and there are some, recognize that the interpretations of the roles she sang were incomparable, it’s her voice that some people have problems with. We think that at its peak her voice was uniquely beautiful, and she created exceptional operatic characters that in other interpretations seem dull. Even the often mediocre music (and Italian operas are full of it) sounded exciting when she sang. There are none even close to La Divina on the opera stage today, and we don’t expect to hear anybody of that rank anytime soon.Permalink

was born on December 2nd of 1923. It feels very strange that’s already been a century since her birth, as her presence is felt as strongly today as on the day she died in 1977: her instantly recognizable voice could be heard on classical music radio stations, on streaming services, on YouTube and (still) on CDs. The means have changed – back then it was LPs that people were buying and listening to – but she’s as adored as ever. Her Casta Diva alone has been heard on YouTube about 35 million times. Callas was so closely associated with Italian opera – Bellini, Donizetti, Verdi, Puccini – that she seemed Italian, but in fact was American, of Greek descent. She married an Italian, Giovanni Battista Meneghini, and, while they were married used his name with her own as Maria Meneghini Callas. She moved to Greece in 1940 and studied voice at the Athen Conservatory. There, she sang in the opera for the first time, appearing as Tosca in 1942. She returned to the US in 1945 but soon left for Italy. Tulio Serafin, the famous conductor who coached generations of singers, became her mentor. In 1947, at the Arena of Verona, he conducted Callas in her first Italian role, as La Gioconda in Ponchielli’s eponymous opera. Her appearance was tremendously successful and brought her career to a different level. During that time she often sang in the rarely produced bel canto operas, mostly because she was the only one who could sing these very difficult roles. She was exceptional as Donizetti’s Anna Boleyn, as Imogene and Norma in Bellini’s Il Pirata and Norma, Lucia in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, Lady Macbeth and Violetta in Verdi's Macbeth and Traviata, and, of course, as Tosca. For three years she sang in smaller theaters, then, in 1950, she appeared, as Aida in La Scala. Even though her relationship with the management was troubled, in the 1950s La Scala became Callas’s home. Neither did Callas have a rapport with Rudolph Bing, the manager of the Met, where she premiered only in 1956. She had a reputation as a temperamental diva, but many of her colleagues thought that it was her exactness that made her difficult to work with. Later in the 1950s, she started experiencing problems with her voice, which may have contributed to her sometimes-erratic behavior. Some think that it was the loss of weight that affected her voice; in the early 1950s Callas was rather heavy, but then went on a diet and lost about 80 pounds. By the late 1950s, her vibrato was too heavy, sometimes the voice was forced and one could hear pronounced harshness, even though other performances were still excellent. Overall, Callas sang at the top of her form for just 10 years but what glorious years they were! Even her detractors, and there are some, recognize that the interpretations of the roles she sang were incomparable, it’s her voice that some people have problems with. We think that at its peak her voice was uniquely beautiful, and she created exceptional operatic characters that in other interpretations seem dull. Even the often mediocre music (and Italian operas are full of it) sounded exciting when she sang. There are none even close to La Divina on the opera stage today, and we don’t expect to hear anybody of that rank anytime soon.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: November 20, 2023. The Spaniards and a bit of Genealogy. Three Spanish composers were born this week: Manuel de Falla, on November 23rd of 1876, Francisco Tárrega, on November 21st of 1852, and Joaquin Rodrigo, on November 21st of 1901. Falla is probably the most important of the three – some might say the most important Spanish composer of the 20th century – although Tárrega was also instrumental in advancing Spanish classical music, which prior to the arrival of Tárrega and his friends Albéniz and Granados had been stagnant for many decades, practically since the death of Padre Antonio Soler in 1783. (It’s interesting to note that the Spanish missed out almost completely on symphonic music). Falla’s most interesting works were composed for the stage: the drama La Vida Breve, ballets El Amor Brujo and Three-Cornered Hat, the zarzuela (a Spanish genre that incorporates arias, songs, spoken word, and dance) Los Amores de la Inés. A fine pianist, he also composed many pieces for the piano, Andalusian Fantasy among them. Tárrega’s preferred instrument was the guitar: he was a virtuoso player, and he also composed mostly for the instrument. (Tárrega had a unique guitar with a very big sound, made by one Antonio Torres, a famous luthier). Here’s one of his best-known pieces, Recuerdos de la Alhambra (Memories of the Alhambra), performed by Sharon Isbin.

1901. Falla is probably the most important of the three – some might say the most important Spanish composer of the 20th century – although Tárrega was also instrumental in advancing Spanish classical music, which prior to the arrival of Tárrega and his friends Albéniz and Granados had been stagnant for many decades, practically since the death of Padre Antonio Soler in 1783. (It’s interesting to note that the Spanish missed out almost completely on symphonic music). Falla’s most interesting works were composed for the stage: the drama La Vida Breve, ballets El Amor Brujo and Three-Cornered Hat, the zarzuela (a Spanish genre that incorporates arias, songs, spoken word, and dance) Los Amores de la Inés. A fine pianist, he also composed many pieces for the piano, Andalusian Fantasy among them. Tárrega’s preferred instrument was the guitar: he was a virtuoso player, and he also composed mostly for the instrument. (Tárrega had a unique guitar with a very big sound, made by one Antonio Torres, a famous luthier). Here’s one of his best-known pieces, Recuerdos de la Alhambra (Memories of the Alhambra), performed by Sharon Isbin.

Rodrigo also wrote mostly for the guitar: his most famous piece is Concierto de Aranjuez, from 1939, for the guitar and orchestra. Here’s the concerto’s first movement; John Williams is the soloist; Daniel Barenboim leads the English Chamber Orchestra. The recording is almost fifty years old, from 1974, but still sounds very good.

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, Johann Sebastian’s eldest son and a wonderful composer in his own right, was born on November 22nd of 1710. Here’s our entry about Wilhelm Friedemann from some years ago. We sympathize with Friedemann: he was brooding, mostly unhappy, and quite unlucky, but he wrote music that we find superior to that of his much more famous brother, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. And here’s an interesting historical tidbit: one of Wilhelm Friedemann’s harpsichord pupils was young Sara Itzig, daughter of Daniel Itzig, a Jewish banker of Frederick II the Great of Prussia. Daniel, one of the few Jews with full Prussian citizenship, had 13 children; Sara was born in 1761. She was a brilliant keyboardist and commissioned and premiered several pieces by Wilhelm Friedeman and CPE Bach. Sara married Salomon Levy in 1783 and had an important salon in Berlin. One of her sisters, Bella Itzig, married Levin Jakob Salomon; they had a son, Jakob Salomon, who upon converting to Christianity, took the name Bartholdy. His daughter Lea married Abraham Mendelssohn, son of the famous Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn. Lea and Abraham had two children, Felix and Fanny Mendelssohn; their full name was Mendelssohn Bartholdy. Sara had a big influence on the musical education of her grandnephew Felix. Bella gave a manuscript of Johann Sebastian Bach’s St Matthew Passion to her grandson in 1824; Felix conducted the first 19th-century revival of the Passion in 1829. So, there’s a line, quite convoluted but fascinating, going from the Bach family to Felix (and Fanny) Mendelssohn. The Itzigs were a remarkable family: in addition to all the connections above, two other sisters, Fanny and Cecilie Itzig, were patrons of Mozart. Maybe we’ll get to that someday.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: November 13, 2023. Transitioning. Not in the sense of Classical Connect’s gender identity, but as a state of mind, which being in Rome largely is. CC is back in the US, but already missing Rome.

Papa Mozart (Leopold) was born this week, in 1719. He was a minor composer and music teacher but is remembered as the father of his genius son, whose career he managed (or exploited, as some would say) for many years.

as some would say) for many years.

Johann Nepomuk Hummel was born on November 14th of 1778 in Pressburg (now Bratislava). When he was eight, the family moved to Vienna. Like Mozart, he was a child prodigy: according to his father, he could read music at the age of four, and at the age of five he could play the piano and the violin very well. In 1786, Hummel was offered music lessons by none other than Mozart, who also housed him for two years, all free of charge. Even though Mozart was 22 years older than the boy, they played billiards and spent time together. At the age of nine Hummel performed one of Mozart’s piano concertos. Very much like Leopold Mozart, Hummel’s father took his child on a European tour. They ended up in London and stayed there for four years, Hummel taking lessons from Muzio Clementi. In 1791, Haydn, who knew the young Hummel from his visits to Mozart’s house in Vienna, was also staying in London; he dedicated a piano sonata to the boy, who performed it in public to great success. The French Revolution, the Terror and the subsequent wars changed the Hummels’s plans, and in 1793 they returned to Vienna. There Hummel continued taking music lessons, with Antonio Salieri and Joseph Haydn. One of Haydn’s pupils was Beethoven; the young men became friends. Hummel played at Beethoven’s memorial concert in 1827, and there he met Franz Schubert, who later dedicated his last three piano sonatas (some of the greatest piano music ever written) to Hummel.

In 1804 Hummel succeeded Haydn as the Kapellmeister to Nikolaus II, Prince Esterházy in Eisenstadt. He stayed there for seven years, returning to Vienna in 1811. After successfully touring Europe with his singer-wife and working in Stuttgart, Hummel settled in Weimar, being offered the position of the Kapellmeister at the Grand Duke’s court. He arrived there in 1819 and stayed for the rest of his life (Hummel died in 1837), making numerous touring trips in the meantime. He became friends with Goethe and turned the city into a major music center. At the court theater, he staged and conducted new operas by Weber, Rossini, Auber, Meyerbeer, Halévy, and Bellini. He also established one of the first pension plans for retired musicians, sometimes playing benefit concerts to replenish the funds. In 1832, Goethe died, Hummel’s health was failing, and he semi-retired, formally retaining his position of the Kapellmeister. Hummel died five years later.

During his lifetime, Hummel was one of the most celebrated pianists in the world and a very popular composer. He was also an important cultural figure, a music entrepreneur, and a famous, sought-after, and very expensive piano teacher. As a composer, he was a transitional figure between the Classical style and Romanticism. Even though he heavily influenced many composers of his time, Chopin and Schumann among them, nowadays Hummel’s music is mostly forgotten. He wrote operas, sacred music, many orchestral pieces, concertos, chamber music, and of course numerous piano pieces. Very little of it is still performed. Here’s Hummel’s Piano Sonata no. 4, Op.38. It’s played by the Korean pianist Hae-Won Chang.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: November 6, 2023. Rome, II. Classical Connect is still in Rome. On Saturday we went to a Santa Cecilia concert with Antonio Pappano conducting the Accademia's Orchestra and Igor Levit playing Beethoven's Third Piano Concerto. But we'd like to start with a decidedly non-musical detail. The Santa Cecilia Hall, inaugurated in 2002, was designed by the famous Italian architect, Renzo Piano. Many of Piano's pieces are airy and light, but not this one. It has little ambiance, despite the use of wood, and looks uninviting. The seating, which follows that of the Berliner Philharmonie, is placed all around the orchestra in shallow layers. We're not sure about the acoustics of the hall, as this was our first visit and we've never heard the Accademia Orchestra live, so it's not clear if the numerous imbalances (shrill winds, for example) are the orchestra's fault or the hall's.

But the most fascinating part of the hall's design is the men's bathroom. It has no urinals, only cabins. Men stand in line, not sure which cabin is empty, and enter one that's just vacated. When things get tough, they go around knocking on doors. The question is, were the urinals eliminated as a gesture of support for some feminist causes, or was Signor Piano not aware of how most men's toilets are usually (and efficiently) constructed?

But let’s get back to music. The program consisted of Cherubini’s Anacréon overture, Beethoven's Third Piano Concerto, Sibelius’s En Saga, and Richard Strauss’s Till Eulenspiegel.

Pappano’s entrance was accompanied by thunderous applause. The wind’s first entrance in the Cherubini was not a happy event. Things got better as they moved along, but even though Beethoven rated Cherubini highly, it’s little surprise that his music is played rarely these days.

Beethoven's Third Piano Concerto was a very different story. Igor Levit was superb. His technique seems to have improved since the last time we heard him in Chicago, and his command of the piece was total, even if one may disagree with some of his tempi. The performance was greeted ecstatically, and he played, exquisitely, an encore, Brahms’s Intermezzo in A major, Op. 118.

After the intermission, Pappano presented Sibelius with a speech and made the audience sing a tune from what was to follow. That was much more entertaining than the En Saga itself. The choice of the final piece, Till Eulenspiegel, would seem rather unusual, as the winds are not this orchestra's strong suit, but it went well, better than one might have expected judging by the three previous pieces.

If you add a hair-raising ride in a Roman taxi to the concert and back, this was, overall, quite an exhilarating event.Permalink