Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: October 30, 2023. Rome, I. Classical Connect is in Rome this week, so this entry is short. Rome overwhelms visually: the sites, interiors of churches worthy of museums, and Roman museums, some of the best in the world. And of course, the magical Roman light. Aurally, things are very different: the usual cacophony of crowds and the ever-jammed traffic, the sirens of the police cars and ambulances trying to get through, and awful street musicians, strategically positioned where the largest crowds congregate but also wandering the streets, assailing the dining public with their renditions of the European schlagers of the 1980s.

Historically, Rome has always been one of the greatest musical centers of Europe, and there are dozens of places, from the Vatican to the palaces of the cardinals and nobility, that are linked to major musical events of the past, but sometimes these connections take a different shape, quite literally: the enormous Borghese palace, which is still the major residence of the family (part of the palazzo is occupied by the Spanish embassy) is nicknamed Il Cembalo, and its plan does look like a harpsichord, with the narrowest side facing the Tiber.

In the next couple of days, Antonio Pappano will be conducting the orchestra of the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in a program of Cherubini, Beethoven (Piano Concerto no. 3 with Igor Levit), Sibelius and Strauss’s Till Eulenspiegel. The site classictic.com, which sells tickets online, decided that the composer of the last piece is Johann Strauss.

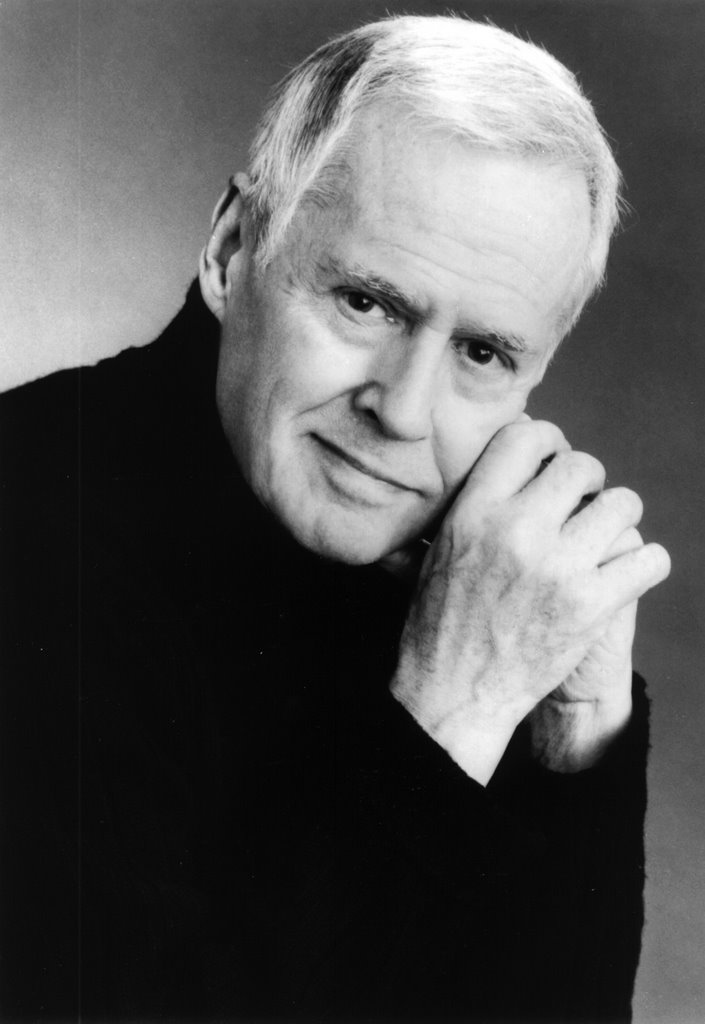

PermalinkThis Week in Classical Music: October 23, 2023. Short notes, II. Today is Ned Rorem’s 100th anniversary. Rorem died last year, just days short of his 99th birthday. He was a wonderful composer of songs and a whimsical writer. He spent almost a decade in France, where for a while he studied with Arthur Honegger (rather than Nadia Boulanger, as many American composers and pianists had done). In 1966 he published a book, Paris Diaries, based on his real diaries, full of gossip, gay stories, and a good read overall. In addition to about 500 art songs, some exceptionally good, he wrote two full-length operas, one of which, Our Town, based on a play by Thornton Wilder, was successfully staged in the US and abroad (he also wrote several smaller, one-act operas). In addition to that he composed three symphonies and a lot of piano music, including two concertos, but none of that music was as successful as his songs. Here is Rorem’s Sonnet. Susan Graham is accompanied by the pianist Malcolm Martineau and Ensemble Oriol.

composer of songs and a whimsical writer. He spent almost a decade in France, where for a while he studied with Arthur Honegger (rather than Nadia Boulanger, as many American composers and pianists had done). In 1966 he published a book, Paris Diaries, based on his real diaries, full of gossip, gay stories, and a good read overall. In addition to about 500 art songs, some exceptionally good, he wrote two full-length operas, one of which, Our Town, based on a play by Thornton Wilder, was successfully staged in the US and abroad (he also wrote several smaller, one-act operas). In addition to that he composed three symphonies and a lot of piano music, including two concertos, but none of that music was as successful as his songs. Here is Rorem’s Sonnet. Susan Graham is accompanied by the pianist Malcolm Martineau and Ensemble Oriol.

If Rorem wrote about 500 art songs, Domenico Scarlatti, who was born on October 26th of 1685, wrote more than 500 piano sonatas. They are mostly short, about as long as Rorem’s songs. Domenico was born in Naples, where his father, the renowned opera composer Alessandro Scarlatti, was working as maestro di capella at the court of the Spanish Viceroy of Naples. Though a thoroughly Italian composer, his link with Spain lasted throughout his life. He moved to Spain in 1729 and lived there for the remaining 25 years of his life.

Another Italian, Luciano Berio, was also born this week, on October 24th of 1925. He was one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. You can read more about him here.

Niccolo Paganini and Georges Bizet both had their anniversaries this week, as did a minor but talented Russian composer of liturgical music, Alexander Gretchaninov. Next year is his 160th anniversary, so we’ll dedicate a post to him.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: October 16, 2023. Short notes. It could’ve been a pretty good week, considering the talent we could celebrate, but the horrendous events of October 7th and their aftermath overwhelmed everything else. So, we’ll go over our list very briefly. The Italian composer Luca Marenzio was born on October 18th, 1553 (or 1554) in Coccaglio, near Brescia. Marenzio was one of the most prolific (and famous) composers of madrigals of the second half of the 16th century. Marenzio was lucky in finding great benefactors. For many years he had served at the court of Cardinal Luigi d’Este, son of Ercole II d'Este, Duke of Modena and Ferrara. After the cardinal’s death, Marenzio found employment with Cardinal Cinzio Aldobrandini, nephew of Pope Clement VIII, and later, with Ferdinando I de' Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany. We can assume that while in Florence, he met the three Florentine composers whose lives we had followed closely in our recent posts – Giulio Caccini, Jacopo Peri, and Emilio de' Cavalieri, but while he inhabited the same intellectual circles as the three, Marenzio never got interested in their ideas about monody and opera. He did, nevertheless, write music for two out of six intermedi to the play La Pellegrina, composed for the wedding of the Grand Duke Ferdinando to Christina of Lorraine in 1589 (Cavalieri oversaw the production and composed one of the intermedi, Caccini composed another one, Peri was both composer and a singer). That same year Marenzio returned to Rome and went on an adventurous trip to Poland, to the court of King Sigismund III Vasa in Warsaw. He stayed in Poland for a year, got seriously ill there, and returned to Rome, where he died in 1599.

aftermath overwhelmed everything else. So, we’ll go over our list very briefly. The Italian composer Luca Marenzio was born on October 18th, 1553 (or 1554) in Coccaglio, near Brescia. Marenzio was one of the most prolific (and famous) composers of madrigals of the second half of the 16th century. Marenzio was lucky in finding great benefactors. For many years he had served at the court of Cardinal Luigi d’Este, son of Ercole II d'Este, Duke of Modena and Ferrara. After the cardinal’s death, Marenzio found employment with Cardinal Cinzio Aldobrandini, nephew of Pope Clement VIII, and later, with Ferdinando I de' Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany. We can assume that while in Florence, he met the three Florentine composers whose lives we had followed closely in our recent posts – Giulio Caccini, Jacopo Peri, and Emilio de' Cavalieri, but while he inhabited the same intellectual circles as the three, Marenzio never got interested in their ideas about monody and opera. He did, nevertheless, write music for two out of six intermedi to the play La Pellegrina, composed for the wedding of the Grand Duke Ferdinando to Christina of Lorraine in 1589 (Cavalieri oversaw the production and composed one of the intermedi, Caccini composed another one, Peri was both composer and a singer). That same year Marenzio returned to Rome and went on an adventurous trip to Poland, to the court of King Sigismund III Vasa in Warsaw. He stayed in Poland for a year, got seriously ill there, and returned to Rome, where he died in 1599.

Franz Liszt was also born this week, on October 22nd of 1811 in a small Hungarian village next to the border with Austria. One interesting snippet about Liszt that we were not aware of till recently: he didn’t speak Hungarian. Two fine Soviet pianists, Emil Gilels and Yakov Flier, both excellent interpreters of Liszt’s music, also have their anniversaries this week: Gilels was born on October 19th, 1916 in Odesa, Flier – on October 21st, 1912 – in a small town of Orekhovo-Zuyevo not far from Moscow.

Baldassare Galuppi and Georg Solti were also born this week, but as with so much else, we’ll leave them for better days.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: October 8, 2023. Verdi, War. Today is the 210th anniversary of Giuseppe Verdi’s birth, but we’re not in the mood to celebrate it: it seems inappropriate with the war raging in Israel and Gaza after the Hamas barbaric terrorist attack. There are many trite sayings about the power of music to heal, to make peace, but they all seem shallow in comparison to the news of civilians being killed in cold blood or the horror of the Israeli kids being abducted by Hamas into Gaza. If anything, throughout history music has been used to make war, from military bands leading troops into battle to Nazis using it in concentration camps. (And no, the Ride of the Valkyries wasn’t used in Vietnam by the US helicopter pilots, it was Francis Ford Coppola’s brilliant invention).

war raging in Israel and Gaza after the Hamas barbaric terrorist attack. There are many trite sayings about the power of music to heal, to make peace, but they all seem shallow in comparison to the news of civilians being killed in cold blood or the horror of the Israeli kids being abducted by Hamas into Gaza. If anything, throughout history music has been used to make war, from military bands leading troops into battle to Nazis using it in concentration camps. (And no, the Ride of the Valkyries wasn’t used in Vietnam by the US helicopter pilots, it was Francis Ford Coppola’s brilliant invention).

We thought of maybe using parts of Verdi’s Requiem or the famous chorus of the Hebrew Slaves, Va', pensiero (Fly, my thoughts), from his opera Nabucco, but that didn’t feel right either. So we’ll leave it at that.

Two great pianists were also born this week, Evgeny Kissin, who’ll turn 52 tomorrow, and Gary Graffman, who will celebrate his 95th birthday on the 14th of October. Both are Jewish; Kissin was born in Russia (then the Soviet Union), Graffman’s parents came from Russia. Hamas, if they could, would like to kill all Jews, no matter where they live. And they would definitely not spare musicians.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: October 2, 2023. Giulio Caccini. During the last couple of months, we’ve published several entries on two subjects: one, the musical transition from the Renaissance to the Baroque and early opera, and another, about some unsavory but talented characters in music. The protagonist of today’s entry falls into both categories. Giulio Caccini was born in Rome on October 8th, 1551. One episode that puts him into the “unsavory” category happened in 1576 when Caccini was in Florence employed by the court of Grand Duke Francesco I de’ Medici. Francesco had a brother, Pietro, who was married to the beautiful Eleonora (Leonora) di Garzia di Toledo. Pietro was known to be gloomy and violent, the marriage was unhappy, and Leonora had several affairs. Caccini, attempting to curry favors from the Duke’s family, spied on Leonora and then denounced her and her lover, Bernardino Antinori, to Pietro. Pietro brought Leonora to Villa Medici at Cafaggiolo, where he strangled her with a dog leash. Leonora was 23. Bernardino Antinori was imprisoned and also killed. The whole story is even more sordid and involves other characters and victims, but though fascinating, it goes even further into Italian history and away from music. One note: if the name of Antinori sounds familiar to wine lovers, it’s not by chance – Bernardino’s family has been making wines since 1385. These days Antinori produce some of the best Chiantis and Super-Tuscans in Italy.

Renaissance to the Baroque and early opera, and another, about some unsavory but talented characters in music. The protagonist of today’s entry falls into both categories. Giulio Caccini was born in Rome on October 8th, 1551. One episode that puts him into the “unsavory” category happened in 1576 when Caccini was in Florence employed by the court of Grand Duke Francesco I de’ Medici. Francesco had a brother, Pietro, who was married to the beautiful Eleonora (Leonora) di Garzia di Toledo. Pietro was known to be gloomy and violent, the marriage was unhappy, and Leonora had several affairs. Caccini, attempting to curry favors from the Duke’s family, spied on Leonora and then denounced her and her lover, Bernardino Antinori, to Pietro. Pietro brought Leonora to Villa Medici at Cafaggiolo, where he strangled her with a dog leash. Leonora was 23. Bernardino Antinori was imprisoned and also killed. The whole story is even more sordid and involves other characters and victims, but though fascinating, it goes even further into Italian history and away from music. One note: if the name of Antinori sounds familiar to wine lovers, it’s not by chance – Bernardino’s family has been making wines since 1385. These days Antinori produce some of the best Chiantis and Super-Tuscans in Italy.

Other episodes are not as gruesome but still attest to Caccini’s character. Two more talented composers worked at the court at the same time, Emilio de' Cavalieri and Jacopo Peri. In 1600, the wedding of Henry IV of France and Maria de' Medici was a very important event. Cavalieri, who oversaw all major festivities of the house of Medici, was expected to direct this one as well. The conniving Caccini had him denied the position, and while Cavalieri did write some of the music, it was Caccini who managed the staging (we described this event here). The disappointed Cavalieri left Florence never to return. As for Peri, the stories are more comical. Upon learning that Peri was writing an opera, Euridice, for the wedding of Maria de' Medici to Henry IV, he rushed to compose his own version using the same libretto and had it published before the first performance of Peri’s work. That wasn’t all; Caccini’s daughter Francesca, a talented singer, was to participate in the performance of Peri’s Euridice. Even though Peri wrote the music for the whole opera, Caccini rewrote the parts performed by Francesca and several other singers under his command, all that just to spite Peri and promote himself. Francesca Caccini, by the way, turned into an excellent composer in her own right. Her opera, La liberazione di Ruggiero dall’isola d’Alcina (The Liberation of Ruggiero from the Island of Alcina) was just staged by the Chicago Haymarket Opera Company (yesterday was the last performance).

composers worked at the court at the same time, Emilio de' Cavalieri and Jacopo Peri. In 1600, the wedding of Henry IV of France and Maria de' Medici was a very important event. Cavalieri, who oversaw all major festivities of the house of Medici, was expected to direct this one as well. The conniving Caccini had him denied the position, and while Cavalieri did write some of the music, it was Caccini who managed the staging (we described this event here). The disappointed Cavalieri left Florence never to return. As for Peri, the stories are more comical. Upon learning that Peri was writing an opera, Euridice, for the wedding of Maria de' Medici to Henry IV, he rushed to compose his own version using the same libretto and had it published before the first performance of Peri’s work. That wasn’t all; Caccini’s daughter Francesca, a talented singer, was to participate in the performance of Peri’s Euridice. Even though Peri wrote the music for the whole opera, Caccini rewrote the parts performed by Francesca and several other singers under his command, all that just to spite Peri and promote himself. Francesca Caccini, by the way, turned into an excellent composer in her own right. Her opera, La liberazione di Ruggiero dall’isola d’Alcina (The Liberation of Ruggiero from the Island of Alcina) was just staged by the Chicago Haymarket Opera Company (yesterday was the last performance).

Even though Caccini wrote three operas, he’s better remembered for his collection of songs called Le nuove musiche (the New Music), published in 1602. Here are two songs from this collection, Amor, io parte and Alme luci beate, but the whole collection is wonderful. In this 1983 recording, the soprano is Montserrat Figueras, the wife of Jordi Savall, who accompanies her on the Viola da Gamba (Figueras died in 2011). Hopkinson Smith is playing the lute.Permalink

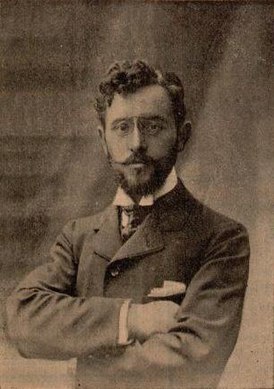

This Week in Classical Music: September 25, 2023. Florent Schmitt. We have to admit that we’re fascinated with the “bad boys” of music. They are invariably “boys,” as there are no “bad girls” in music historiography that we’re aware of. As for the male composers, there are plenty, Richard Wagner being the quintessential one. In the last couple of years, we’ve written about several of them, mostly the Germans in the 20th century, even though they are not the only ones: there were plenty of baddies in the Soviet bloc and, in a very different way, several Italians of the Renaissance. This week it’s Florent Schmitt’s turn, a French composer infamous for shouting “Vive Hitler!” during a concert. (Dmitri Shostakovich was also born this week, and, as talented as he was, he was no angel either, but we’ll return to Shostakovich another time). Schmitt was born on September 28th of 1870 in the town of Meurthe-et-Moselle, Lorraine, the area that was passing from France to Germany and back for centuries – thus the German name. At 17, he entered the conservatory in nearby Nancy, and two years later moved to Paris where he studied composition with Gabriel Fauré and Jules Massenet. While in Paris, Schmitt became friends with Frederick Delius, the English composer of German descent who was then living in Paris. In the 1890s he befriended Ravel and met Debussy.

girls” in music historiography that we’re aware of. As for the male composers, there are plenty, Richard Wagner being the quintessential one. In the last couple of years, we’ve written about several of them, mostly the Germans in the 20th century, even though they are not the only ones: there were plenty of baddies in the Soviet bloc and, in a very different way, several Italians of the Renaissance. This week it’s Florent Schmitt’s turn, a French composer infamous for shouting “Vive Hitler!” during a concert. (Dmitri Shostakovich was also born this week, and, as talented as he was, he was no angel either, but we’ll return to Shostakovich another time). Schmitt was born on September 28th of 1870 in the town of Meurthe-et-Moselle, Lorraine, the area that was passing from France to Germany and back for centuries – thus the German name. At 17, he entered the conservatory in nearby Nancy, and two years later moved to Paris where he studied composition with Gabriel Fauré and Jules Massenet. While in Paris, Schmitt became friends with Frederick Delius, the English composer of German descent who was then living in Paris. In the 1890s he befriended Ravel and met Debussy.

Schmitt tried to get the prestigious Prix de Rome five times, submitting five different compositions every year from 1896 to 1900, when he finally won it with the cantata Sémiramis. He spent three years in Rome and then traveled extensively, visiting Russia and North Africa, among other places. One of his most popular pieces composed during the period after Rome is the Piano Quintet op. 51 (1902-1908). Schmitt dedicated it to Fauré. Here’s the final movement, Animé, performed by the Stanislas Quartet with Christian Ivaldi at the piano. The ballet La tragédie de Salomé was composed during the same period, in 1907. Igor Stravinsky was taken by it; in Grove’s quote, he wrote to Schmitt: “I am only playing French music – yours, Debussy, Ravel’. And later, “I confess that [Salomé] has given me greater joy than any work I have heard in a long time.” In 1910 Schmitt created a concert version of the ballet. Here’s the second part of it (the New Philharmonia Orchestra is conducted by Antonio de Almeida). It’s not surprising that Stravinsky liked it, as it clearly presages parts of Rite of Spring. Another important piece, Psalm XLVII, was written in 1906.

During WWI Schmitt wrote music for military bands but returned to regular composing once the war was over. He also worked as a music critic for the newspaper Le Temps. Schmitt was a nationalist with pronounced sympathies toward the Nazi regime. The episode we referred to at the beginning of this entry happened in November of 1933. During a concert of the music of Kurt Weill, a Jewish composer who had beenrecently forced into exile by the Nazis, he stood up and shouted “Vive Hitler!” According to a witness, he added: “We already have enough bad musicians to have to welcome German Jews.” That makes him not only a Nazi sympathizer but also an antisemite. During the German occupation of France, Schmitt collaborated with the Vichy government and was a member of the Music section of the France-Germany Committee. He visited Germany and in December of 1941 went to Vienna to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Mozart’s death. After the liberation, Schmitt was investigated as a collaborator, but these proceedings were later dropped, although a year-long ban was imposed on performing and publishing his music. Soon after everything was forgotten and in 1952, just seven years after the end of the war, Schmitt was made the Commander of the Legion of Honor. In 1996, the controversial past of this "one of the most fascinating of France's lesser-known classical composers," as he’s often described, came into prominence again, and his name was removed from a school and a concert hall.Permalink