Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

November 5, 2018. Couperin and much more. François Couperin, Couperin le Grand, one of the greatest French composers of the end of the 17th – early 18th century, was born in Paris on November 10th of 1668. The most important French composer between Lully and Rameau, he was featured on these pages many times, for example here. We know him mostly as a composer for the harpsichord and the organ, but Couperin wasn’t confined to keyboard instruments. In 1714 he wrote the three Leçons de ténèbres (literally, Lessons of Darkness), vocal settings for the Tenebrae service, held during the three days preceding Easter. During the traditional Catholic service candles are extinguished, and the service ends in total darkness. The text is from the biblical Lamentations of Jeremiah. Many composers set the Ténèbres to music, especially during the Renaissance era, for example, Palestrina, Thomas Tallis and, famously, Orlando di Lasso. Couperin’s setting is among the best. Here is the third Leçon for two sopranos; it’s performed by Montserrat Figueras and Maria Cristina Kiehr, Jordi Savall conducts Le Concert Des Nation.

November 10th of 1668. The most important French composer between Lully and Rameau, he was featured on these pages many times, for example here. We know him mostly as a composer for the harpsichord and the organ, but Couperin wasn’t confined to keyboard instruments. In 1714 he wrote the three Leçons de ténèbres (literally, Lessons of Darkness), vocal settings for the Tenebrae service, held during the three days preceding Easter. During the traditional Catholic service candles are extinguished, and the service ends in total darkness. The text is from the biblical Lamentations of Jeremiah. Many composers set the Ténèbres to music, especially during the Renaissance era, for example, Palestrina, Thomas Tallis and, famously, Orlando di Lasso. Couperin’s setting is among the best. Here is the third Leçon for two sopranos; it’s performed by Montserrat Figueras and Maria Cristina Kiehr, Jordi Savall conducts Le Concert Des Nation.

Walter Gieseking, a French-German pianist, was also born this week, on November 5th of 1895. Gieseking was born in Lyon; his father was a well-known German doctor. He began playing the piano at the age of four and didn’t receive any formal training till he entered the Hamburg Conservatory at the age of 16. When he was 20, still in Hamburg, he performed a cycle of almost all Beethoven sonatas; it was extremely well received. He then performed several very successful concerts in Berlin; his playing of the music of Debussy and Ravel was especially noted. While some of his compatriots emigrated, Gieseking stayed in Germany during the Nazi period; Vladimir Horowitz and Arthur Rubinstein both accused him of being a Nazi collaborator. After the war, he was practically banned from performing in the US but continued playing in the more forgiving Europe. He eventually was cleared of cultural collaboration and returned to the US. He was known is an outstanding performer of the music of Debussy and Ravel. Here’s the 1953 recording Gieseking made in London of Debussy’s Image, Book I. Gieseking died in London on October 26th of 1956. At the time he was in London, recording the full cycle of Beethoven’s sonatas. He was in the process of recording Sonata no. 15, Op. 28 (“Pastoral”) when he suddenly fell ill. By then, the first three movements had been already recorded; it was never finished. This incomplete recording was issued by HMV.

Ivan Moravec, a wonderful Czech pianist, is not as well known as he probably should be. He was born on November 9th of 1930 and died three years ago, on July 27th of 2015. Moravec studied in Prague and later with Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli in Arezzo. Moravec’s playing wasn’t flashy but probing, highly musical and faithful to the composer’s ideas. He was rightly considered an exquisite performer of Chopin’s music. He was also wonderful in Ravel and Debussy – someday we’ll play his performances parallel to Gieseking’s. Here’s Chopin’s Nocturne, No. 1 In B-flat minor recorded in 1966.Permalink

October 29, 2018. John Dunstaple. Vincenzo Bellini was born this week, on November 3rd of 1801 (here’s the final scene from La Pirata, with Maria Callas and the Philharmonia orchestra conducted by Nicola Rescigno). Also, two wonderful conductors: Eugen Jochum, on November 1st of 1902, and Giuseppe Sinopoli, on November 2nd of 1946. Jochum, one of the most interesting interpreters of the music of Bruckner, was a long-time conductor of the Hamburg Philharmonic, which he directed during the Nazi era (Jochum never joined the Nazi party or any other Nazi organizations). After the war he became the founding music director of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. He also had long-term relationships with the Concertgebouw Orchestra and other major orchestras. Here’s the first movement of Bruckner’s Symphony no. 6. Jochum conducts “his” Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra.

conducted by Nicola Rescigno). Also, two wonderful conductors: Eugen Jochum, on November 1st of 1902, and Giuseppe Sinopoli, on November 2nd of 1946. Jochum, one of the most interesting interpreters of the music of Bruckner, was a long-time conductor of the Hamburg Philharmonic, which he directed during the Nazi era (Jochum never joined the Nazi party or any other Nazi organizations). After the war he became the founding music director of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. He also had long-term relationships with the Concertgebouw Orchestra and other major orchestras. Here’s the first movement of Bruckner’s Symphony no. 6. Jochum conducts “his” Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra.

The Italian conductor Giuseppe Sinopoli was only 54 when he died of a heart attack while conducting Aida at the Deutsche Oper, Berlin. He was best known as an opera conductor, having worked at the Bayreuth, the Metropolitan opera and most opera houses if Europe. He led the Staatskapelle Dresden for almost 10 years. Like Johum, Sinopoli made several interesting recordings of Bruckner; he was also an insightful Mahlerian. Here Sinopoli is conducting the Vienna Philharmonic in Robert Schumann’s Manfred Overture, Op. 115.

We find John Dunstaple’s music irresistible. Duntsaple was born around 1390, about the same time as the famous Burgundian, Guillaume Dufay. In England, Dunstaple was followed by Robert Morton (born around 1430), Walter Lambe (1453), John Taverner (1490), Thomas Tallis (1505), William Byrd (1540), John Dowland, John Bull (both born in 1563), and Orlando Gibbons (1583). These are just the more famous names; the tradition of the Early English Renaissance is quite remarkable. Dunstaple served in the court of John of Lancaster, a son of king Henry IV and a brother of Henry V. John led the British forces in many battles of the Hundred Year War with France (he was the one to capture Joan of Arc). It’s likely that for several years Dunstaple stayed in Normandy, where John was the Governor. From there his music spread over the continent. Considering that a major war was raging in France, that is quite remarkable. Dunstaple’s influence was very significant, especially affecting musicians of the highly developed Burgundian school; the reason was both musical and political, as Burgundy was allied with England in its war against France. The poet Martin Le Franc, a contemporary of Dunstaple, came up with the term La Contenance Angloise, which could be loosely translated as “English manner” and said that it affected the two greatest composers of Burgundy, Guillaume Dufay and Gilles Binchois. Dunstaple probably returned to England after John’s death in 1435; he served in the court of Humphrey of Lancaster, John’s brother. In addition to writing music Dunstaple studied mathematics, astronomy and astrology. He died in 1453. When, during the reign of Henry VIII England became Protestant, many monasteries – the main keepers of musical tradition – were "dissolved" and their libraries ruined. Most of the English manuscripts of Dunstaple’s music were lost. Fortunately, many copies remained in Italy and Germany – evidence of Dunstaple’s international fame. About 50 compositions are currently attributed to him (these attributions are sometimes challenged). Among these are two masses, a number of sections from different masses, and many motets. Here’s Dunstaple’s Quam pulchra es. It’s performed by the Hilliard Ensemble, Paul Hillier conducting. Permalink

October 22, 2018. Liszt, Berio, Bizet, Paganini, Scarlatti. What a wonderful group! All born this week – that’s why they appear together in this entry – but how different, as if to demonstrate to us, yet again, the enormous breadth of the European musical tradition. Here we have Domenico Scarlatti, a great representative of the Baroque clavichord tradition; Niccolò Paganini, a famous violinist and gifted composer, Franz Liszt, a Romantic composer and legendary pianist: he wrote some of the most exquisite music for the piano (a successor to the harpsichord, Scarlatti’s instrument); Georges Bizet, the French opera composer (Scarlatti’s father, Alessandro, who also wrote operas, wouldn’t have recognized the genre); and finally, Luciano Berio, another Italian, and one of the most interesting composers of the second half of the 20th century. We’ve written about all of them before, so we’ll present each of them with a piece of music.

to us, yet again, the enormous breadth of the European musical tradition. Here we have Domenico Scarlatti, a great representative of the Baroque clavichord tradition; Niccolò Paganini, a famous violinist and gifted composer, Franz Liszt, a Romantic composer and legendary pianist: he wrote some of the most exquisite music for the piano (a successor to the harpsichord, Scarlatti’s instrument); Georges Bizet, the French opera composer (Scarlatti’s father, Alessandro, who also wrote operas, wouldn’t have recognized the genre); and finally, Luciano Berio, another Italian, and one of the most interesting composers of the second half of the 20th century. We’ve written about all of them before, so we’ll present each of them with a piece of music.

Domenico Scarlatti was born on October 26th of 1685, a prodigious year that also gave us Johann Sebastian Bach and George Frideric Handel. Scarlatti wrote 555 keyboard sonatas. Here’s one of them Sonata in B minor, K. 27, L. 449, performed by Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli.

While Scarlatti composed mostly for the harpsichord, Niccolò Paganini (born on October 27th of 1782) wrote much of his music for his favorite instrument, the violin. Here’s the devilishly difficult Caprice No. 3 in octave double stops. It’s performed by Augustin Hadelich, a young Italian violinist of German descent, who won a Grammy in 2016.

Franz Liszt, born on October 22nd of 1811, was for the piano what Paganini was for the violin, and more (he really was a much better composer). In 1838, Liszt wrote Grandes études de Paganini, S.140, a set of six etudes after Paganini’s works; five of the etudes are based on Paganini’s Caprises and one, on the themes from his violin concertos. In 1851 Liszt published a revised version, S. 141, which was, while still formidable, not as demanding technically as the almost unplayable original version. The second one is the version that’s usually played in concerts, but Nikolai Petrov, a wonderful Soviet pianist, made a live recording of the first version. Here’s La Chasse,Étude No. 5 in E major.

Georges Bizet was born on October 25th of 1838. He lived just 37 years and didn’t even witness the success of his major opera, Carmen: Bizet died after the first 33 Paris performances, where the public was more scandalized than amused, while the real triumph was achieved when, within the next several years, Carmen went international. Here’s one of the best Carmens of the 20th century, Elena Obraztsova, in the famous Habanera. The Philharmonia Orchestra is conducted by Giuseppe Patané.

Luciano Berio, the youngest of the group by almost a century, was born on October 24th of 1925. Here’s his 1975 composition called Chemins IV, scored for the oboe and 13 string instruments. It’s based on Berio’s earlier 1969 composition, Sequenza VII. Chemins is performed by Heinz Holliger, oboe, and The London Sinfonietta directed by the composer himself.Permalink

October 15, 2018. Gilels and Flier. Last week we were celebrating the life of Monserrat Caballé, and missed the birthday of one of her stage partners, the incomparable Luciano Pavarotti, who was born on October 12th of 1935 in Modena. We mentioned a recording he made in 1984 with Joan Sutherland and Caballé. Here’s the trio from Act I of Bellini’s Norma: Pavarotti is Pollione, Sutherland, who was 58 at the time of the recording, is Norma and Caballé – Adalgisa.

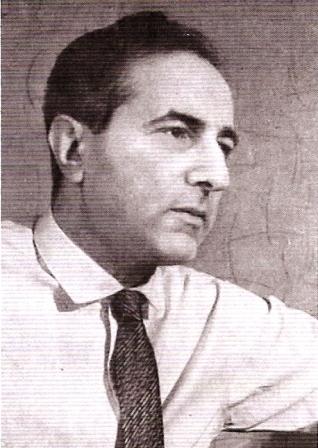

Two great Soviet pianists were also born this week in what was then the Russian Empire: Emil Gilels on October 19th of 1916 and Yakov Flier, on October 21st of 1912. Gilels was born in Odessa (now in Ukraine), Flier – in a small town not far from Moscow. Both were Jewish; with few exception (the rich merchants, the highly educated) Jews were not allowed to live outside of the Pale of Settlement, in the western part of the Empire. How Flier’s parents, a poor family of a watchmaker, managed to live so close to Moscow, isn’t clear.

Gilels, a child prodigy, started his piano studies at the age of five and a half. By the age of 12 he had acquired a considerable repertoire, gave his first recital and was accepted at the Odessa Conservatory. In 1933, at the age of 16, he won the First All-Union Competition of Musicians-Performers. That made him famous and allowed him to perform across the country. In 1935-38 he studied with Heinrich Neuhaus, the famed Moscow Conservatory teacher. By that time Yakov Flier was his main competitor: in 1936 Gilels lost to Flier at the International piano competition in Vienna, where Flier took the first prize, while Gilels took the second, but two years later he had his revenge at the Ysaÿe International Festival in Brussels (after the war this competition would be renamed the Queen Elizabeth): Gilels won and Flier took third place (Moura Lympany came in second). The Second World War put the breakes on Gilels’s international career: he was scheduled to play in the US in 1939 but the tour was canceled. After the war, the great Sviatoslav Richter became his main competitor and eventually overtook him in the Soviet hierarchy, which always needed one person at the top. This had little to do with Gilels’s real achievements: in 1955 he made his US debut, which was highly successful; he played in a trio with Leonid Kogan and Mstislav Rostropovich; he was invited to every major concert hall of Europe. Gilels had a heart attack in 1981 from which he never completely recovered. He died on October 14th of 1985.

Conservatory. In 1933, at the age of 16, he won the First All-Union Competition of Musicians-Performers. That made him famous and allowed him to perform across the country. In 1935-38 he studied with Heinrich Neuhaus, the famed Moscow Conservatory teacher. By that time Yakov Flier was his main competitor: in 1936 Gilels lost to Flier at the International piano competition in Vienna, where Flier took the first prize, while Gilels took the second, but two years later he had his revenge at the Ysaÿe International Festival in Brussels (after the war this competition would be renamed the Queen Elizabeth): Gilels won and Flier took third place (Moura Lympany came in second). The Second World War put the breakes on Gilels’s international career: he was scheduled to play in the US in 1939 but the tour was canceled. After the war, the great Sviatoslav Richter became his main competitor and eventually overtook him in the Soviet hierarchy, which always needed one person at the top. This had little to do with Gilels’s real achievements: in 1955 he made his US debut, which was highly successful; he played in a trio with Leonid Kogan and Mstislav Rostropovich; he was invited to every major concert hall of Europe. Gilels had a heart attack in 1981 from which he never completely recovered. He died on October 14th of 1985.

Yakov Flier was somewhat of a late starter. He studied with the famous Konstantin Igumnov but wasn’t a star at the Conservatory. He graduated in 1934 and only then did his career take off. After several triumphs at international competitions he became as famous as Gilels. His style, though, was very different, more romantic, sometimes verging on exalted, and so was his repertoire, Romantic at the core – Liszt and Chopin were his favorites, together with Rachmaninov (he also played compositions by contemporary Soviet composers, like Prokofiev, Shostakovich and Kabalevsky). Tragically, his career was cut short: around 1945 he developed a problem in his right hand, which progressed; by 1949 he stopped playing recitals. Flier resumed his solo career in 1959-1960; though not as much a virtuoso as before, his playing had by then acquired the depth which he sometimes lacked in his earlier years. Here’s a live recording of Schumann’s Symphonic Etudes Op. 13 made in 1960.

After several triumphs at international competitions he became as famous as Gilels. His style, though, was very different, more romantic, sometimes verging on exalted, and so was his repertoire, Romantic at the core – Liszt and Chopin were his favorites, together with Rachmaninov (he also played compositions by contemporary Soviet composers, like Prokofiev, Shostakovich and Kabalevsky). Tragically, his career was cut short: around 1945 he developed a problem in his right hand, which progressed; by 1949 he stopped playing recitals. Flier resumed his solo career in 1959-1960; though not as much a virtuoso as before, his playing had by then acquired the depth which he sometimes lacked in his earlier years. Here’s a live recording of Schumann’s Symphonic Etudes Op. 13 made in 1960.

A year ago, we wrote two entries about an old photo depicting a group of six young Soviet musicians; Gilels and Flier were among them. You can read them here and here. More on Gilels is here.Permalink

October 8, 2018. Caballé and Verdi. Only three of the 20th century sopranos were ever given affectionate monikers by their adoring fans: “La Divina,” “La Stupenda,” and “La Superba” were indeed the greatest. La Divina – Maria Callas – died years ago, in 1977, she was just 53; La Stupenda – Joan Sutherland – just three years younger than Callas, lived a much longer life, and her singing career was also longer; she died in 2010. We were going to write about Giuseppe Verdi, as his birthday happens to be this week, but on Saturday welearned that La Superba, Monserrat Caballé, had died in Barcelona after a long illness. Caballé was an extraordinary singer. She had a real bel canto technique, a huge vocal diapason that allowed her to sing coloratura arias, and an incomparable repertoire of more than 100 operas. But more than anything else she was known for the purity of her voice and amazing vocal control that allowed her to sustain a long and even pianissimo line.

Stupenda – Joan Sutherland – just three years younger than Callas, lived a much longer life, and her singing career was also longer; she died in 2010. We were going to write about Giuseppe Verdi, as his birthday happens to be this week, but on Saturday welearned that La Superba, Monserrat Caballé, had died in Barcelona after a long illness. Caballé was an extraordinary singer. She had a real bel canto technique, a huge vocal diapason that allowed her to sing coloratura arias, and an incomparable repertoire of more than 100 operas. But more than anything else she was known for the purity of her voice and amazing vocal control that allowed her to sustain a long and even pianissimo line.

Monserrat Caballé was born in Barcelona on April 12th, 1933. She studied at the Barcelona Conservatory and graduated in 1954 with a gold medal. She then moved to Basel, sung in the Basel Opera and then in Bremen. In 1960, she appeared in a small role in La Scala. Her breakthrough came in 1965 when she replaced, on short notice, Marilyn Horne in a New York concert staging of Donizetti’s Lucrezia Borgia. The public didn’t know her, but she earned a 25-minute ovation. That evening launched her to stardom, which stayed with her for the rest of her life. That year, 1965, she made her debut at the Glyndebourne in such diverse roles as Marschallin in Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier and Countess in Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro. Later that year she sung for the first time at the Metropolitan Opera, where she would sing for the next 20 years, appearing on stage 98 times. She went on to conquer every major opera house in the world. She officially premiered at La Scala in 1970, and two years later at London’s Covent Garden and the Lyric Opera in Chicago. In 1974, when La Scala was visiting Moscow, she sung a phenomenal Norma. Bellini’s Norma had a special place in Caballé’s repertoire. She was one of the greatest Normas of all time and recorded it in 1972 with Domingo as Pollione. Twelve years later she made another recording, in which she sung Adalgisa, the role usually sung by a mezzo. In that historic recording, Luciano Pavarotti was Pollione. She partnered with the best tenors of the time, Franco Corelli, Giuseppe Di Stefano and Jose Carreras (and of course with Domingo many times, and Pavarotti).

We mentioned that Caballé had an unusually large repertoire. She sung most of the bel canto roles, the German and French operas, the Spanish zarzuelas, but throughout her career Verdi was in the center. And as we’d still like to celebrate the great Italian, we offer several samples from his operas. Here is D'amor sull'ali rosee, from Il Trovatore. This recording was made in 1974. Orquesta Sinfonica de Barcelona is conducted by Gianfranco Masini. Also in 1974, Caballé recorded Aida. Here’s O Patria mia from Act III. Riccardo Muti leads the New Philharmonia Orchestra. Earlier, in 1968, she recorded this aria from Due Foscari, which isn’t performed very often (RCA Italiana orchestra is under the direction of Antón Guadagno). And finally, from 1971, Ave Maria from Otello. Antón Guadagno again, but this time conducting the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.Permalink

October 1, 2018. CCCC. It’s easy to remember and, if you’re interested in contemporary music, very much worth checking out. CCCC stands for Chicago Center for Contemporary Composition. The recently established organization will present its inaugural season starting with a concert on October 13th by Yarn/Wire performing music by the Japanese composer Misato Mochizuki, Enno Poppe, a German composer and conductor, and two young Chicagoans. Like most of the season’s concerts it will take place at the University of Chicago’s Logan Center for the Arts, 915 E 60th Street.

a concert on October 13th by Yarn/Wire performing music by the Japanese composer Misato Mochizuki, Enno Poppe, a German composer and conductor, and two young Chicagoans. Like most of the season’s concerts it will take place at the University of Chicago’s Logan Center for the Arts, 915 E 60th Street.

The UChicago has a long tradition of presenting new music, beginning with the Contemporary Chamber Players under Ralph Shapey in 1964 and continuing as Contempo in 2002 under Shulamit Ran and in 2015 under Marta Ptaszyńska. CCCC is led by one of the most interesting contemporary American composers Augusta Read Thomas (here, for example, is her Angel Musings, performed by the Orion Ensemble, and here – Aureole, performed by the DePaul University Symphony, Cliff Colnot conducting). A key component of the Center’s performance series is the newly formed Grossman Ensemble which comprises 13 leading contemporary music specialists. Even the selection of the instruments comprising the ensemble is unusual: a flute,oboe, clarinet, saxophone, horn, two sets of percussion, harp, piano plus the Grammy-nominated Spektral Quartet. The ensemble is co-directed by Ms. Thomas and two other young composers, Anthony Cheung, and Sam Pluta, both from the University’s Music department.

University Symphony, Cliff Colnot conducting). A key component of the Center’s performance series is the newly formed Grossman Ensemble which comprises 13 leading contemporary music specialists. Even the selection of the instruments comprising the ensemble is unusual: a flute,oboe, clarinet, saxophone, horn, two sets of percussion, harp, piano plus the Grammy-nominated Spektral Quartet. The ensemble is co-directed by Ms. Thomas and two other young composers, Anthony Cheung, and Sam Pluta, both from the University’s Music department.

Over the course of the season, the Grossman Ensemble will participate in three performances at the Logan Center for the Arts, all with a focus on the process of creating new work. Eight rehearsals will lead up to each performance, enabling composers to write, workshop, and review new works in close collaboration with the ensemble. The public will be invited to attend an open rehearsal before each concert, allowing them unprecedented access to the creative process. In this inaugural season, the Grossman ensemble will workshop and perform 12 world premieres by University of Chicago faculty, students, and guest composers in the concert season.

In addition to the Grossman Ensemble and Yarn/Wire, Tyshawn Sorey, a composer and performer working at the intersection of classical and jazz music, will play with his trio. And on February 5th of 2019 nine UChicago composers will have a unique occasion to be heard in a performance by the Civic Orchestra of Chicago, a training orchestra for the Chicago Symphony: all of them were asked to create new works to be premiered by this outstanding professional ensemble.

Seven more established composers (“established” being a relative term for a contemporary classical composer) have been commissioned to write new works. They include Steve Lehman, who writes jazz and experimental music (his most recent album was called the #1 Jazz Album of the year by NPR Music and the Los Angeles Times); David Rakowski, a two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist and recipient of many international prizes; Carlos Sanchez-Gutierrez, also a multiple prize-winner; composer and soprano Kate Soper, a Pulitzer Prize finalist whose works have been commissioned by many America orchestras; Chen Yi, known for blending Chinese and Western traditions in her music; and Shulamit Ran (here is her For an Actor: Monologue for Clarinet in a virtuosic performance by Alexander Fiterstein (Clarinet).

We strongly encourage our listeners to give this wonderful undertaking a try.Permalink