Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

July 2, 2018. Cluck and Mahler. Christoph Gluck was born on this day in 2014. We wrote about him a year ago, so for now here ’s the chorus Chaste fille de Latone’ from Act 4 of Gluck’s opera Iphigénie en Tauride. Many noted the similarity between this chorus and March of the Priests from Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte (here). This of course is not to compare the genius of the younger composer and the considerable but still limited talents of Christoph Willibald Gluck.

Like the Fifth, the Sixth symphony was composed at Maiernigg, a small village near the resort town of Maria Wörth in Carinthia, in his “composing hut.” Mahler conducted the premier in 1906. The symphony is often subtitled “Tragic”; even though it’s not on the original score, one of the Vienna concerts which Mahler conducted had this sobriquet printed on the program, so clearly, he agreed with it. This is rather paradoxical, considering that it was written when everything seemed to be going well in Mahler’s life, and many real tragedies that befell him were still to come. The symphony consists of four movement: 1. Allegro energico, ma non troppo. Heftig, aber markig (Violent but succinct); 2. Scherzo: Wuchtig (powerful); 3. Andante moderato; and 4. Finale: Sostenuto – Allegro moderato – Allegro energico. That was the sequence of the movement when the score was initially published. Then, while rehearsing, Mahler decided to move around two inner sections, playing the slow Andante moderato first, followed by the Scherzo. Apparently, that’s how he performed it on the premier and that’s how it was performed for a while. Then, in 1919, Alma Mahler sent a telegram to Willem Mengelberg, with "First Scherzo then Andante" in it. Even though Mengelberg had performed the symphony following Mahler’s later order, with the Andante preceding the Scherzo, he obeyed Alma’s direction. This is the order in which most conductors perform the Symphony these days, and this’s how Leonard Bernstein plays it with the Vienna Philharmonic orchestra in the 1989 recording. Here are: Allegro, Scherzo, Andante, Finale.Permalink

June 25, 2018. Claudio Abbado. We may be wrong about Gustave Charpentier, but it seems not a single significant composer was born this week. As for Charpentier, who was born on this day in 1860, he’s known for just one composition, the opera Louise, which was premiered (to great success, we might add) in 1900. One aria is still being performed quite often on the concert scene – Depuis le jour. You can hear it nicely sung by Anna Netrebko. The Prague Philharmonia is conducted by Emmanuel Villaume.

As long as we’re lacking composers with known birth dates, let’s mention one from the older ages. Alessandro Striggio, an Italian, was born around 1536 into an aristocratic Mantuan family. In 1559 he moved to Florence, to the court of Cosimo I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. Apparently, he was close to the Duke, as in 1567 Cosimo sent him on a diplomatic mission to London. Later Striggio traveled to Austria and Bavaria. In 1584 Alfonso II d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, invited Striggio for a short visit. At the time, Ferrara was known as one of the musical centers of Italy (and, by extension, of the world); one of the jewels of the court was a group of virtuoso female singers called concerto di donne. Later, Striggio visited Ferrara several more times. In 1587 he moved back to his native Mantua, were he served at the court of Vincenzo Gonzaga. Striggio died in Mantua of a fever on February 29th of 1592. At the time the 25-year-old Claudio Monteverdi was a viola player at the court. Here’s Striggio’s famous motet Ecce Beatam Lucem. It’s performed by Ensemble Huelgas under the direction of Paul van Nevel.

Beatam Lucem. It’s performed by Ensemble Huelgas under the direction of Paul van Nevel.

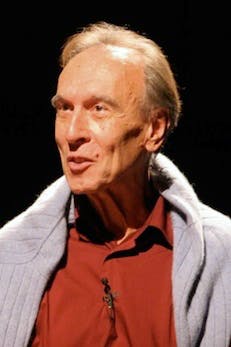

Claudio Abbado, one of the greatest conductors of the “post-Karajan” era, was born in Milan on June 26th of 1933. As a youngster he went to Wilhelm Furtwängler and Arturo Toscanini’s rehearsals (he found Toscanini’s dictatorial manner unpleasant). Abbado attended the Milan Conservatory, where he studied piano and conducting. Upon graduating, he spent some time in Vienna; there he befriended Zubin Mehta and listened to the rehearsals of Bruno Walter and Karajan. He conducted his first public symphony concert in 1958, and one year later he led a performance of Prokofiev’s The Love for Three Oranges. In 1960 he successfully debuted at La Scala (in 1969 he became the theater’s resident conductor). Abbado’s career took off in the 1970s: he was invited to the major opera theaters, such as Covent Garden and the Vienna Staatsoper. In 1984 he became the music director of the Vienna opera. All along he was extensively performing with symphony orchestras, often programming the music of the 20th century. He became the Principal conductor of the London Symphony and the principal guest conductor of the Chicago Symphony. In 1990, upon the death of Herbert von Karajan, the Berlin Philharmonic selected Abbado as its next conductor. In 2000 Abbado had major surgery for stomach cancer, which severely affected his performance schedule. After formally leaving the Berlin Philharmonic in 2002 he continued working with many orchestras, but especially with the European Union Youth Orchestra, which he co-founded in 1978, the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra, which he founded in 1986, and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe.

Abbado’s discography is vast and of extremely high quality, but he was especially well known as a superb interpreter of the music if Mahler. Here he conducts the Vienna Philharmonic. The mezzo is Federica von Stade.Permalink

June 18, 2018. Marcello, Rozhdestvensky, Levine. Benedetto Marcello, a gifted Italian composer of the late Baroque, was born on June 24th of 1686 in Brescia. We’d like to get to his interesting Requiem in the Venetian Manner, but for now we’ll direct you to our earlier entry about Benedetto and his brother Alessandro, as we have more urgent topics.

First, some sad news: Gennady Rozhdestvensky, one of the best Soviet conductors, died on June 16th in Moscow. Rozhdestvensky was born on May 4th of 1931 into a musical family: his father was the noted conductor Nikolai Anosov, his mother – a singer, Natalia Rozhdestvenskaya. Gennady studied the piano with Elena Gnesina and Lev Oborin and, later, conducting with his father. He was only 20 when he found himself on the podium of the Bolshoi conducting Sleeping Beauty. From 1961 to 1974 Rozhdestvensky was the music director of the Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra. He was also the music director of the Bolshoi Theater Orchestra. From 1974 to 1985 he was the music director of the experimental Moscow Chamber Music Theater, where he supervised performances of the old Baroque and Classical operas, and also productions of modern operas rarely if ever heard in Russia, like Stravinsky’s The Rake Progress and Shostakovich’s The Nose. Contemporary composers were of special interest to Rozhdestvensky: he often performed works that, if not banned, then were clearly not favored by the Soviet music establishment: Stravinsky, Poulenc, Orff, and the Soviet nonconformist composers like Edison Denisov, Sofia Gubaidulina and Alfred Schnittke. Rozhdestvensky was also a raconteur: very often, before conducting a piece, he would turn toward the audience and deliver a witty introduction. Nobody else did it back then, which probably was a good thing, as few had his knowledge, sense of humor and storytelling skills. In 1974 Rozhdestvensky was hired as the director of the Stockholm Royal Philharmonic, the first Soviet conductor to lead a European orchestra. Later, he worked with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and the Vienna Symphony. He was invited to conduct many major orchestras: the Berlin Philharmonic, the Royal Concertgebouw, the Chicago Symphony. Among his numerous recordings are all of Shostakovich and Prokofiev’s symphonies and also all of Bruckner’s, in different editions. Gennady Rozhdestvensky is survived by his wife of many years, the pianist Victoria Postnikova.

16th in Moscow. Rozhdestvensky was born on May 4th of 1931 into a musical family: his father was the noted conductor Nikolai Anosov, his mother – a singer, Natalia Rozhdestvenskaya. Gennady studied the piano with Elena Gnesina and Lev Oborin and, later, conducting with his father. He was only 20 when he found himself on the podium of the Bolshoi conducting Sleeping Beauty. From 1961 to 1974 Rozhdestvensky was the music director of the Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra. He was also the music director of the Bolshoi Theater Orchestra. From 1974 to 1985 he was the music director of the experimental Moscow Chamber Music Theater, where he supervised performances of the old Baroque and Classical operas, and also productions of modern operas rarely if ever heard in Russia, like Stravinsky’s The Rake Progress and Shostakovich’s The Nose. Contemporary composers were of special interest to Rozhdestvensky: he often performed works that, if not banned, then were clearly not favored by the Soviet music establishment: Stravinsky, Poulenc, Orff, and the Soviet nonconformist composers like Edison Denisov, Sofia Gubaidulina and Alfred Schnittke. Rozhdestvensky was also a raconteur: very often, before conducting a piece, he would turn toward the audience and deliver a witty introduction. Nobody else did it back then, which probably was a good thing, as few had his knowledge, sense of humor and storytelling skills. In 1974 Rozhdestvensky was hired as the director of the Stockholm Royal Philharmonic, the first Soviet conductor to lead a European orchestra. Later, he worked with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and the Vienna Symphony. He was invited to conduct many major orchestras: the Berlin Philharmonic, the Royal Concertgebouw, the Chicago Symphony. Among his numerous recordings are all of Shostakovich and Prokofiev’s symphonies and also all of Bruckner’s, in different editions. Gennady Rozhdestvensky is survived by his wife of many years, the pianist Victoria Postnikova.

And now another date, that could’ve been joyful but isn’t. On June 23 James Levine, who lead the Metropolitan Orchestra for 40 years, will turn 75. A conductor of enormous talent, two years ago he was credibly accused of sexually abusing his students and younger colleagues. This is terrible, and our perception of his art will never be the same. Levine had a brilliant career, which started with his apprenticeship with George Sell at the Cleveland, whose assistant he soon became. Guest-conducting major orchestras followed, as did a long association with the Chicago Symphony (he was the music director of the Ravinia Festival for 20 years). In 1971, he was invited to conduct the Metropolitan Opera orchestra in Tosca; a year later he was offered the position of Principal conductor and in 1975 became the Music Director. He built the orchestra into a world class ensemble, which, except for the Vienna Philharmonic, has no rivals among opera bands. His 1990 Ring cycle, with

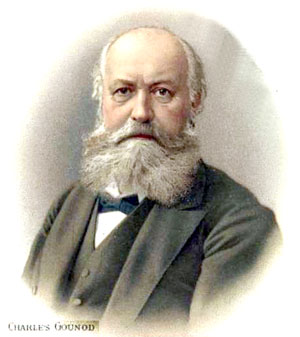

James Morris, Christa Ludwig and Siegfried Jerusalem, telecast on PBS, was a cultural event.All these achievements are now clouded. For a while the Met itself engaged in a Soviet-style rewriting of history, eliminating any mention of Levine on their Our Story page, as was discovered by the NY Times; since then, his name has reappeared. PermalinkJune 11, 2018. Gounod at 200. Charles Gounod was born on June 18th of 1818 in Paris. Though we know him as an opera composer who influenced George Bizet, Jules Massenet and Camille Saint-Saëns, the young Gounod started with writing church music. After graduating from the Paris Conservatory, where he took classes from Fromental Halévy and winning the Prix de Rome, he spent time in Italy studying the music of Palestrina. There he composed a Mass and a Requiem; upon returning to Paris he enrolled in a seminary. In 1848, though, he pivoted and got involved with opera. He was friends with the famous mezzo Pauline Viardot, one of the most respected singers of her time; through her he got a commission from the Paris Opéra. It was quite a coup for an unknown composer. (Viardot lived a long life: she died in 1910 at the age of 88. Very popular, she knew practically “everybody” worth knowing – composers, writers, painters. She had famous lovers, including the Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev, who eventually settled in the Viardo household. Pauline had a sister, Maria Malibran, also a singer and one of the greatest mezzos of the 19th century at that. Malbran’s voice range stretched from contralto to high soprano. She excelled in the operas of Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti. Malibran’s life was much shorter: she fell from a horse and died at the age of 28).

the Paris Conservatory, where he took classes from Fromental Halévy and winning the Prix de Rome, he spent time in Italy studying the music of Palestrina. There he composed a Mass and a Requiem; upon returning to Paris he enrolled in a seminary. In 1848, though, he pivoted and got involved with opera. He was friends with the famous mezzo Pauline Viardot, one of the most respected singers of her time; through her he got a commission from the Paris Opéra. It was quite a coup for an unknown composer. (Viardot lived a long life: she died in 1910 at the age of 88. Very popular, she knew practically “everybody” worth knowing – composers, writers, painters. She had famous lovers, including the Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev, who eventually settled in the Viardo household. Pauline had a sister, Maria Malibran, also a singer and one of the greatest mezzos of the 19th century at that. Malbran’s voice range stretched from contralto to high soprano. She excelled in the operas of Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti. Malibran’s life was much shorter: she fell from a horse and died at the age of 28).

Gounod’ first opera, titled Sapho was premiered in April of 1851. It failed with the public but gained some critical success, enough for the Opéra management to give Gounod another commission, the opera La nonne sanglante (The Bloody Nun). That one was also a failure, even though the libretto was written by the very popular Eugène Scribe. Four years later, in 1858, Gounod wrote a comic opera Le médecin malgré lui (The Doctor in spite of himself) based on a farce by Molière. It was yet another flop. Surprisingly, despite these financial disasters, opera directors were still ready to stage Gounod’s operas. In 1856 Jules Barbier and Michel Carré presented Gounod with a libretto called “Faust.” It was based on Carré's play Faust et Marguerite which in turn was loosely based on Goethe’s Faust, Part I. Léon Carvalho, the director of the Théâtre Lyrique, agreed to produce it. After a significant postponement, Faust was premiered in March of 1859. The opera wasn’t very successful, but neither was it a failure; the Théâtre Lyrique didn’t drop it and eventually the public reaction turned quite positive. After Gounod added a ballet intermission, it was staged at the Opéra to great success, and it eventually became the Paris Opéra’s most popular production. One of the greatest Méphistophélès of all time was the Russian bass Feodor Chapiapin. Here’s a recording of the famous “couplets” (Song of the Golden Calf) from Act I. It was made in 1928-1930. And here’s the finale of a wonderful 1958 recording, with Nicolai Gedda singing Faust, Victoria de los Ángeles as Marguerite and Boris Christoff as Méphistophèles. André Cluytens conducts the Orchester and the Chorus of the Théâtre National de l’Opéra.

In 1866 Gounod wrote one more opera that could be considered successful, Roméo et Juliette. It was very well received at the premiere, but eventually faded. His other operas – after Faust he wrote seven more, not counting Roméo et Juliette – fared much worse. In 1884 he stopped actively composing. Gounod died in 1893; he was given a state funeral which took place at the Church of the Madeleine (“The immense crowd filled the Place de la Madeleine” wrote the New York Times the next day). Adelina Patti, “the finest singer who ever lived” according to Giuseppe Verdi, presented an enormous bouquet at the service. Camille Saint-Saëns played the organ and Gabriel Fauré conducted the orchestra.Permalink

June 4, 2018. Schumann, Albinoni, Argerich, Mravinsky. Robert Schumann, one of the greatest Romantic composers, was born on June 8th of 1810. We celebrate him often, and we’ve published several longer articles about Schumann’s wonderful song cycles, such as Dichterliebe (here and here), and Frauenliebe und -leben (here). So today we’ll just play some of his music. Here’s Schumann’s Kinderszenen, recorded by Martha Argerich in 1983. More about Ms. Argerich below.

Tomaso Albinoni is best remembered today for “Albinoni’s Adagio.” The problem is that at best this music is based on some fragment composed by Albinoni, but it likely has nothing to do with him at all: that is, at least, what Remo Giazotto, an Italian musicologist who “discovered” the piece, was claiming at the end of his life. But this controversy aside, Albinoni, who was born on June 8th of 1671, was a fine, if not necessarily a major, Baroque composer. A Venetian, Albinoni was, unlike so many of his colleagues, quite well-to-do: his father was a wealthy merchant. During his lifetime, Albinoni was known for his operas. He wrote at least 50 of them; Albinoni himself claimed that he composed more than 80. His first opera, Zenobia, was produced in Venice in 1694; his last, Artamene, almost half a century later, in 1741. Most of the scores were lost during the firebombing of Dresden at the end of WWI. Practically none of his operas are staged these days. His oboe concertos, on the other hand, are still very popular. Here, for example, is Albinoni’s Concerto for oboe and strings in D minor Op. 9, no. 2. Ensemble Il Fondamento is directed by the oboe soloist, Paul Dombrecht.

this music is based on some fragment composed by Albinoni, but it likely has nothing to do with him at all: that is, at least, what Remo Giazotto, an Italian musicologist who “discovered” the piece, was claiming at the end of his life. But this controversy aside, Albinoni, who was born on June 8th of 1671, was a fine, if not necessarily a major, Baroque composer. A Venetian, Albinoni was, unlike so many of his colleagues, quite well-to-do: his father was a wealthy merchant. During his lifetime, Albinoni was known for his operas. He wrote at least 50 of them; Albinoni himself claimed that he composed more than 80. His first opera, Zenobia, was produced in Venice in 1694; his last, Artamene, almost half a century later, in 1741. Most of the scores were lost during the firebombing of Dresden at the end of WWI. Practically none of his operas are staged these days. His oboe concertos, on the other hand, are still very popular. Here, for example, is Albinoni’s Concerto for oboe and strings in D minor Op. 9, no. 2. Ensemble Il Fondamento is directed by the oboe soloist, Paul Dombrecht.

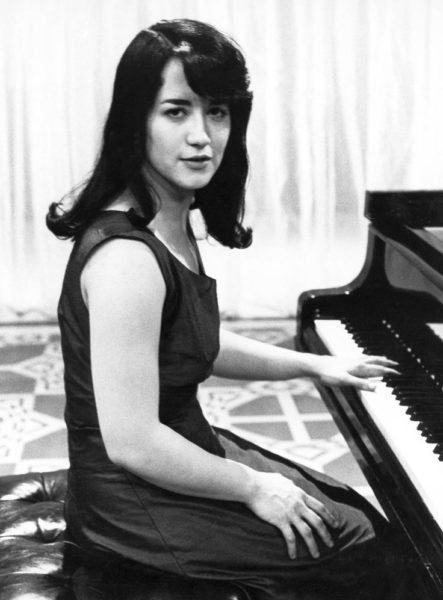

It’s hard to imagine that Martha Argerich will turn 77 tomorrow, she brings so much energy and youth to piano-playing: even though she doesn’t perform often, when she does she generates a thrill like nobody else – read, for example, a review of her October 2017 concert at Carnegie Hall. Argerich (her last name is pronounced Ar-khe-rich in Spanish, although American announcers usually pronounce it with a “g,” not “kh,” and make a mess of the last consonant) was born in Buenos Aires. She’s Catalan Spanish on her father’s side and Russian Jewish on the maternal side. Argerich started playing piano at the age of three and studied music in Buenos Aires till the age of 14, when her family moved to Europe. There among her teachers were Friedrich Gulda, Maria Curcio, Abbey Simon, and Nikita Magaloff. She also took several lessons with Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli. At the age of 16 she won two competitions in a row, the 1957 Geneva Competition and the Feruccio Busoni. In 1965, Argerich won the Chopin competition in Warsaw; her playing there caused a sensation. That year she made her US debut. Very soon she was acknowledged as one of the most exciting pianists of the generation. Her recital career was rather short: since the early 1980s she practically stopped appearing on stage solo, citing “loneliness,” but continued to play chamber music and piano concertos. Argerch often plays with the pianists Nelson Freire, her old friend, and Stephen Kovacevich,her former husband, the violinist Gidon Kremer and the cellist Mischa Maisky. Here’s another example of Martha Argerich’s art: Bach’s English Suite No. 2 BWV 807 in A minor.

thrill like nobody else – read, for example, a review of her October 2017 concert at Carnegie Hall. Argerich (her last name is pronounced Ar-khe-rich in Spanish, although American announcers usually pronounce it with a “g,” not “kh,” and make a mess of the last consonant) was born in Buenos Aires. She’s Catalan Spanish on her father’s side and Russian Jewish on the maternal side. Argerich started playing piano at the age of three and studied music in Buenos Aires till the age of 14, when her family moved to Europe. There among her teachers were Friedrich Gulda, Maria Curcio, Abbey Simon, and Nikita Magaloff. She also took several lessons with Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli. At the age of 16 she won two competitions in a row, the 1957 Geneva Competition and the Feruccio Busoni. In 1965, Argerich won the Chopin competition in Warsaw; her playing there caused a sensation. That year she made her US debut. Very soon she was acknowledged as one of the most exciting pianists of the generation. Her recital career was rather short: since the early 1980s she practically stopped appearing on stage solo, citing “loneliness,” but continued to play chamber music and piano concertos. Argerch often plays with the pianists Nelson Freire, her old friend, and Stephen Kovacevich,her former husband, the violinist Gidon Kremer and the cellist Mischa Maisky. Here’s another example of Martha Argerich’s art: Bach’s English Suite No. 2 BWV 807 in A minor.

Born on June 4th of 1903 in St.-Petersburg, Evgeny Mravinsky was probably the greatest Russian conductor of the 20th century. Last week we played Glinka’s Overture to Ruslan and Lyudmila with Mravinsky conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic. Mravinsky deserves a separate entry, and we’ll write one soon.Permalink

May 28, 2018. Six composer and two pianists. Six composers were born this week: Isaac Albéniz and Erich Wolfgang Korngold on May 29th, the former in 1860, the latter in 1897. Marin Marais, the Frenchman – on May 31st of 1656, Georg Muffat – on June 1st of 1653. We didn’t mention Muffat’s nationality, as it’s hard to determine: he was born to a Scottish father and French mother in the Dutchy of Savoy, which back then was an independent state with Turin as its capital but now is part of France. He studied in Paris for six years and then moved to Alsace, which, formerly part of the Holy Roman Empire, was conquered by the French King Louis XIII in 1639. Even though under the formal control of France, most of Alsace was independent, German-speaking and Lutheran. Later in his life, Muffat lived in Vienna, Prague, Salzburg and Italy. He spent the last 20 years of his life in Passau, Bavaria. We could call Muffat a Savoyard, a Frenchman or even a German, as some encyclopedias do. Here’s his Concerto Grosso in G minor “Dulce Somnium” (Sweet Sleep), written by Muffat in 1701. While in Rome, Muffat studied with Arcangelo Corelli, one of the early developers of the Concerto Grosso form. It was practically unknown in the German lands till Muffat’s time. The performers in this recording are the ensemble Musica Aeterna Bratislava under the direction of Peter Zajíček.

French mother in the Dutchy of Savoy, which back then was an independent state with Turin as its capital but now is part of France. He studied in Paris for six years and then moved to Alsace, which, formerly part of the Holy Roman Empire, was conquered by the French King Louis XIII in 1639. Even though under the formal control of France, most of Alsace was independent, German-speaking and Lutheran. Later in his life, Muffat lived in Vienna, Prague, Salzburg and Italy. He spent the last 20 years of his life in Passau, Bavaria. We could call Muffat a Savoyard, a Frenchman or even a German, as some encyclopedias do. Here’s his Concerto Grosso in G minor “Dulce Somnium” (Sweet Sleep), written by Muffat in 1701. While in Rome, Muffat studied with Arcangelo Corelli, one of the early developers of the Concerto Grosso form. It was practically unknown in the German lands till Muffat’s time. The performers in this recording are the ensemble Musica Aeterna Bratislava under the direction of Peter Zajíček.

Also on June 1st we celebrate the birthday of Mikhail Glinka, the first truly original Russian composer. Glinka was born in 1804; at that time the Russian music scene, quite lively in St-Petersburg, was dominated by the Italians and Italian-influenced composers. Two operas by Glinka, A Life for the Tsar (called Ivan Susanin during the Soviet period) and Ruslan and Lyudmila, changed it all. Here’s the famous Overture to Ruslan and Lyudmila. The Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra is led by its principal conductor of 50 years, Evgeny Mravinsky. And finally, Sir Edward Elgar was born on June 2nd of 1857. As we confessed some years ago, we’re not as much in love with Sir Edward’s music as the British public seems to be. Still, without a doubt Jacqueline du Pré’s performance of Elgar’s Cello concerto is a masterpiece, both in terms of music itself and the interpretation. We’ll write more about it on Elgar’s next birthday.

And now to two pianists. Grigory Ginzburg, a Russian-Soviet-Jewish pianist, was born in Nizhny Novgorod on May 29th of 1904. He studied at the Moscow Conservatory with Alexander Goldenweiser. In 1927 he participated in the First Chopin Piano Competition and received the 4th prize (Lev Oborin was the winner). Ginzburg taught at the Conservatory from the age of 25. His repertory was very 19-century, with many transcriptions and salon pieces, but his musicianship was impeccable. Many consider Ginsburg the last pianist in Liszt’s tradition. Here’s Grigory Ginzburg playing Chopin's Berceuse in a live 1959 recording.

Considered one of the finest pianists of his generation, Zoltán Kocsis, who died of cancer at the age of 64 less than two years ago, was a very different musician. Born on May 30th of 1952 in Budapest, he loved playing music of the 20th century: he recorded all piano works of Béla Bartók. Kocsis was also a conductor, having founded, with Iván Fischer, the Budapest Festival Orchestra. Here’s Bartók’s Piano Sonata (1926), recorded by Kocsis in 1996. Permalink