Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

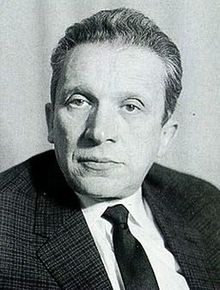

January 6, 2016. Pierre Boulez, the great French composer and conductor, died last night in Baden-Baden, Germany. He was 90. Boulez burst on the European music scene in the aftermath of WWII as one of the leading composers of the Darmstadt School. In 1970 he founded IRCAM and in 1976, Ensemble InterContemporain. He started conducting in the 1960s and in 1971 was made the music director of the New York Philharmonic and the BBC Symphony Orchestra in London. Later he lead the Chicago Symphony and worked with the Concertgebouw and the Berlin Philharmonic. Even though his own musical sensibilities were very different, he became one of the greatest interpreters of the music of Mahler. Boulez wrote and talked about music more intelligently than most of the professional critics. We mourn the passing of this extraordinary figure.

January 4, 2016. Giuseppe Sammartini. Giuseppe Sammartini, not to be confused with his younger brother Giovanni Battista Sammartini, was born on January 6th of 1695 in Milan. Their father, Alexis Saint-Martin, a Frenchman, was an oboist, and he taught the instrument to his children. Both brothers became professional oboists playing in different professional orchestras, including that of the newly-opened Teatro Regio Ducal (this grand opera house burned down in 1776 and was replaced, in 1778, with the Nuovo Regio Ducal Teatro alla Scala, which we now know simply as Teatro alla Scala). Johann Joachim Quantz, a famous flutist and composer, considered Giuseppe the best oboe player in Italy. Sammartini probably also played the flute and the recorder: most oboists of the time played those instruments and Sammartini composed a large number of pieces for these instruments. One of his first compositions, an Oboe Concerto, was published in Amsterdam in 1717. In 1727 Sammartini moved to Brussels and then to London, where he was recognized as a supreme master of the oboe. He remained in England for the rest of his life. He became friendly with the composer Maurice Greene and played solos in the operas of Handel and Bononcini. In 1736 Sammartini accepted a lucrative position as a music teacher to the wife and the children of the Prince of Wales. He remained in this position till his death in 1750.

professional oboists playing in different professional orchestras, including that of the newly-opened Teatro Regio Ducal (this grand opera house burned down in 1776 and was replaced, in 1778, with the Nuovo Regio Ducal Teatro alla Scala, which we now know simply as Teatro alla Scala). Johann Joachim Quantz, a famous flutist and composer, considered Giuseppe the best oboe player in Italy. Sammartini probably also played the flute and the recorder: most oboists of the time played those instruments and Sammartini composed a large number of pieces for these instruments. One of his first compositions, an Oboe Concerto, was published in Amsterdam in 1717. In 1727 Sammartini moved to Brussels and then to London, where he was recognized as a supreme master of the oboe. He remained in England for the rest of his life. He became friendly with the composer Maurice Greene and played solos in the operas of Handel and Bononcini. In 1736 Sammartini accepted a lucrative position as a music teacher to the wife and the children of the Prince of Wales. He remained in this position till his death in 1750.

Sammartini, praised as “the greatest oboist that the world has ever known,” was said to have had a remarkable tone, which had the qualities of the human voice. He was also an influential teacher and helped to create the English oboe school. These days, though, he’s mostly remembered as a fine composer. During his lifetime he was known as a composer of chamber music, especially of flute sonatas and trios. Most of his concertos were published posthumously, but they are the ones that are most popular these days. Here’s his Concerto for the Recorder in F Major. It’s performed by Pamela Thorby, recorder, and the ensemble Sonnerie, Monica Huggett conducting. Sammartini wrote four keyboard concertos; here’s one of them, in A Major. Donatella Bianchi is on the harpsichord, ensemble I Musici Ambrosiani is conducted by Paolo Suppa, conductor. Finally, an Oboe Concerto, in this case, no. 12 in C Major, here. Franscesco Quaranta is playing oboe, also with I Musici Ambrosiani and Paolo Suppa.

Among many other birthdays this week are that of Francis Poulenc, who was born on January 7th of 1899 and Alexander Scriabin, born on January 6th of 1872. Here’s Scriabin’s Piano Sonata no. 10, his last piano sonata. It was composed in 1913, two years before the composer’s death. It’s performed by the American pianist Kathy Kim.Permalink

December 28, 2015. Still in the Christmas mood. So much great music has been written for Christmas that we decided to continue our celebration for a little longer. Last week, when we wrote about Giovanni Gabrieli, we mentioned one of his students, Heinrich Schütz. Schütz was 24 when he went to Venice. Half a century later, in 1660, at the advanced age of 75 he composed Weihnachtshistorie, The Christmas Story. By then he was an eminent composer, the “chief Kapellmeister” at the court of the Elector of Saxony. The Christmas Story is set to the text from the Gospels of Luke and Matthew as translated by Martin Luther. You can hear it in the performance by the Westfalische Kantorei under the direction of Wilhelm Ehmann.

Christmas Story. By then he was an eminent composer, the “chief Kapellmeister” at the court of the Elector of Saxony. The Christmas Story is set to the text from the Gospels of Luke and Matthew as translated by Martin Luther. You can hear it in the performance by the Westfalische Kantorei under the direction of Wilhelm Ehmann.

About 30 years later, around 1690, Arcangelo Corelli composed Twelve Concerti Grossi, his opus 6 (it wasn’t published till 1714). The set was commissioned by Corelli’s then new patron, Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni. Concerto number 8 had an inscription, Fatto per la notte di Natale (Made for the night of Christmas) and became known as the “Christmas Concerto.” It’s performed here, in a somewhat old-fashioned manner, by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Herbert von Karajan conducting. Corelli had many pupils, one of them – Pietro Locatelli, composer and violinist. In 1721 Locatelli, then 26, also composed a set of 12 Concerti Grossi, and called the eighth “Christmas Concerto.” The last section of Corelli’s concert is marked as Largo. Pastorale ad libitum (that is, “at one’s pleasure”); the last section of Locatelli’s – Pastorale (Largo Andante). Not terribly original but lovely, it’s performed here by I Musici.

Let’s return to Germany. Here’s a wonderful hymn, Es ist ein' Ros' entsprungen, which Michael Praetorius included in his first published work, Musae Sioniae (The Muses of Zion) in 1609. The traditional translation of the hymn is “Lo, How a Rose E'er Blooming.” Even though Luther was strongly against the Catholic Marian cult, many of the older Catholic songs made it into the Lutheran liturgy, and Es ist ein' Ros' entsprungen is one of them: the text makes clear that the rosebud is “Mary, the pure.” The crystalline Monteverdi Choir is the performer. 125 years later, Johann Sebastian Bach wrote (and, to some extent, compiled) the great Christmas Oratorio. Consisting of six parts, the music was to be performed on Christmas and two following days, and also on New Year’s Day (the day of the circumcision of Jesus) and on the first Sunday of the new year. Here’s Sinfonia, the introductory part to the Second day service. John Elliot Gardiner conducts the English Baroque Soloists. The Adoration of the Magi, above, is by Domenico Ghirlandaio. It was painted around 1485.

Permalink

December 21, 2015. Giovanni Gabrieli. Several times a year we celebrate composers whose birth dates (and sometimes birth years) remain unknown to us. Giovanni Gabrieli is one of them and it seems quite appropriate to celebrate him this time of the year, as we approach Christmas: Gabrieli was mostly a composer of sacred music. Giovanni was a born in Venice, sometime between 1554 and 1557. His family came from the Alpine area of Carnia, north of Venice. Giovanni was probably brought up by his uncle, Andrea Gabrieli, who was probably his first music teacher. And as his uncle did some years earlier, the young Giovanni traveled to Munich, to the court of the Duke Albert V of Bavaria, to study with the great Orlando di Lasso. He returned to Venice in 1584, and a year later became the organist at the Basilica of San Marco; for several months he shared these responsibilities with Andrea, until Andrea’s death on August 30th of that year. That same year he received another prestigious post, as organist to the Scuola Grande di S Rocco, one of the most important confraternities in Venice. Tintoretto was still working on his famous canvases, decorating the building when Gabrieli assumed his post.

Giovanni traveled to Munich, to the court of the Duke Albert V of Bavaria, to study with the great Orlando di Lasso. He returned to Venice in 1584, and a year later became the organist at the Basilica of San Marco; for several months he shared these responsibilities with Andrea, until Andrea’s death on August 30th of that year. That same year he received another prestigious post, as organist to the Scuola Grande di S Rocco, one of the most important confraternities in Venice. Tintoretto was still working on his famous canvases, decorating the building when Gabrieli assumed his post.

Upon Andrea’s death, Giovanni edited and published a volume of his work; to this volume he also added some of his own compositions. Giovanni’s first major collection of original music, called Sacrae symphoniae, was only published in 1597. Some, if not most, of the pieces in the collection represent music composed for the Scuola. The publication was clearly very successful, as just one year later, in 1598, it was reprinted in Nuremberg. Here’s Sonata Pian'e Forte from the collection, performed by the brass section of the Bavarian State Opera, Zubin Mehta conducting. As Giovanni’s music became famous, pupils started coming from Italy and Europe, many of them sent from Germany. Among them was Heinrich Schütz, who came in 1609 and stayed till Gabrieli’s death. Through Schütz, and other Germans, we can connect Gabrieli with the German baroque tradition and Johann Sebastian Bach.

Gabrieli, like his uncle Andrea and Adrian Willaert before him, wrote much music in the Venetian “polychoral” style. This style has an unusual history: unlike practically anything else in music, its existence was a direct result of the architectural peculiarities of the main cathedral of Venice, the San Marco. San Marco’s shape differs from all other large Italian churches. Instead of having a long, wide nave, it’s built as an equal-armed cross, having the length and the width of about the same size. Additional smaller chapels in both the nave and the transept further complicate the structure. As there is not enough space for one large choir, there are two, on the opposite sides of the church. As a result, the sound echoes throughout the building with the delays forming very unusual effects. Gabrieli wrote a large number of choral and brass pieces that took advantage of these effects. Here’s a great example, Canzon à 12 in Echo. It’s performed by the brass sections of three great orchestras, the Philadelphia, the Cleveland, and the Chicago.

PermalinkDecember 14, 2015. Beethoven! This week we celebrate Ludwig van Beethoven’s 245th birthday. Beethoven was baptized on December 17th of 1770, so it’s often assumed that he was born the previous day, on December 16th. We usually celebrate his birthday by focusing on different periods of his life during which he wrote some of his piano sonatas: last year, for example, we finished with the Piano sonata no. 4, which was published in 1797. This time we’ll change tracks a bit and present a longer article on his two symphonies, no 3, the famous Eroica, and no. 4. We’ll continue the traversal of Beethoven’s piano sonatas later on. You can hear Eroica in the performance by the Berlin Philharmonic under the direction of Herbert von Karajan in the 1984 recording here, and Symphony no. 4, in the live recording made by Carlos Kleiber with the Bavarian State Orchestra in 1982, here. ♫

Eroica in the performance by the Berlin Philharmonic under the direction of Herbert von Karajan in the 1984 recording here, and Symphony no. 4, in the live recording made by Carlos Kleiber with the Bavarian State Orchestra in 1982, here. ♫

Symphony No. 3. With the closing measures of the Symphony No. 2 in D major, Beethoven embarked down the “new road” he announced in a letter to Krumpholz in 1802: “I am not satisfied with my works up to the present time. From today I mean to take a new road.” While this turning point—this new artistic direction—can be seen in the Violin Sonatas, op. 30 or the Piano Sonatas, op. 31, it is most striking apparent in the comparison of the Second Symphony to its successor, the Eroica. Premonitions of Beethoven’s mature style surfaced at times in the first two symphonies—most noticeably in the Minuet of the First and the Finale of the Second. However, the Third Symphony is pure Beethoven as he is so beloved today.

Beethoven began working on the Symphony No. 3 in E-flat shortly after the Second and was occupied with it until early 1804, with much of the actual composition beginning during the summer of 1803. By the spring of 1804, a fair copy of the score had been made, which was openly displayed on Beethoven’s desk. On the outside page written at the very top was the name “Buonaparte,” and at the bottom, “Luigi van Beethoven.” The first suggestion of a symphony in honor of Napoleon Buonaparte had likely been made to Beethoven as early as 1798. At this time, Napoleon was known as a great statesman and a champion of freedom, and had not yet transformed, in his fall from glory, into the tyrant that waged war across Europe. The French Revolution had certainly influenced Beethoven, quite possibly through Bonn’s proximity to France. Indeed, his very character embodied its ideals. Once in Vienna, he was a contradiction to all the expectations of musicians of that day. Besides refusing to enter the service of any of the nobility, he asserted his independence with manners that were off-putting even to his friends and a lack of etiquette or respect towards his professed superiors. He took what was his by right and refused to see them as favors. This freedom of spirit is certainly evident in the earlier symphonies but the Third is its undeniable embodiment. Napoleon had become the quintessence of the French Revolution’s ideals, and it is quite nature that Beethoven should admire him.

However, Beethoven had no knowledge of the changes taking place in Napoleon. On May 2, 1804, the Senate passed a motion asking Napoleon to take the title of Emperor. Later that month, on the 18th, he assumed the title. When the news finally reached Vienna, Ferdinand Ries delivered it to Beethoven. “After all, then, he is nothing but an ordinary mortal! He will trample all the rights of men under foot, to indulge his ambition, and become a greater tyrant than any one,” was the reply that erupted from the composer. In his fury, Beethoven grabbed the score of his new symphony, tore the title page, and threw it on the ground. For seventeen years, Beethoven never mentioned the connection between the work and Napoleon until, on hearing news of Emperor’s death, he replied, “I have already composed the proper music for that catastrophe”—an obvious reference to the Funeral March which forms the symphony’s second movement. On the copy of Beethoven’s score preserved today, one can visibly see the hatred with which Beethoven scratched out Napoleon’s name from the title page. (Continue reading here).Permalink

Weinberg was born in 1919 in Warsaw and fled to the Soviet Union at the outbreak of t WWII when the Germans attacked Poland (his parents and sister perished during the Holocaust). Weinberg wrote twenty-two symphonies and more than 20 quartets, but his music was practically ignored in the Soviet Union, even though many considered him the third most important composer in the country after Prokofiev and Shostakovich. That changed somewhat with the revival of his opera “The Passenger.” The opera tells a story of a German couple on a cruise. The woman seems to recognize a fellow passenger and in a moment of shock, reveals to her husband that she worked as a guard in a concentration camp where the other passenger was an inmate. The harrowing story of the life in the camp is recounted on a lower deck of the ship. A Polish play by Zofia Posmysz, herself a concentration camp survivor, which served as the basis for the opera libretto, was also used by the talented Polish director Andrzej Munk for the screenplay of his 1963 film, “Passenger.” Weinberg’s opera was scheduled for a premiere in 1968 in the Bolshoi Theater but was canceled by the Soviet authorities at the last moment. The first concert performance took place in 2006 in Moscow; the opera was then properly staged in Europe in 2010 and in the US in 2014 (it had its very successful Chicago premier at the Lyric Opera earlier this year). Here’s Weinberg’s instrumental piece, his piano sonata no. 3, op. 31. It’s performed by Murray McLachlan.

Weinberg was born in 1919 in Warsaw and fled to the Soviet Union at the outbreak of t WWII when the Germans attacked Poland (his parents and sister perished during the Holocaust). Weinberg wrote twenty-two symphonies and more than 20 quartets, but his music was practically ignored in the Soviet Union, even though many considered him the third most important composer in the country after Prokofiev and Shostakovich. That changed somewhat with the revival of his opera “The Passenger.” The opera tells a story of a German couple on a cruise. The woman seems to recognize a fellow passenger and in a moment of shock, reveals to her husband that she worked as a guard in a concentration camp where the other passenger was an inmate. The harrowing story of the life in the camp is recounted on a lower deck of the ship. A Polish play by Zofia Posmysz, herself a concentration camp survivor, which served as the basis for the opera libretto, was also used by the talented Polish director Andrzej Munk for the screenplay of his 1963 film, “Passenger.” Weinberg’s opera was scheduled for a premiere in 1968 in the Bolshoi Theater but was canceled by the Soviet authorities at the last moment. The first concert performance took place in 2006 in Moscow; the opera was then properly staged in Europe in 2010 and in the US in 2014 (it had its very successful Chicago premier at the Lyric Opera earlier this year). Here’s Weinberg’s instrumental piece, his piano sonata no. 3, op. 31. It’s performed by Murray McLachlan.

December 7, 2015. This is another unusually bountiful week. Monday the 7th is the birthday of Pietro Mascagni, the composer of Cavalleria Rusticana, one of the two greatest verismo operas. Mascagni was born in 1863 and wrote Cavalleria in 1890. It was premiered earlier than Verdi’s Falstaff, which was staged in 1893. Hard to imagine that Mascagni died in August of 1945: as wonderful as it is, his music belonged to a bygone era. Another Italian, Bernardo Pasquini, one of the most important keyboard composers of the late 17th – early 18th century, was also born on this day, in 1637. Here’s his delightful “Toccata del cucco“ (the Cuckoo toccata), which Ottorino Respighi used practically verbatim in his orchestral suite Gli Uccelli (The Birds). Here, though, it’s played the way Pasquini intended, on a harpsichord. It’s performed by Lorenzo Ghielmi. The following day (the 8th) we have four anniversaries with all four composers coming from the different countries: Jean Sibelius, the great Finnish composer who was born in 1865. Manuel Ponce, probably the best known Mexican composer (Ponce was born in 1882), a very interesting Czech composer Bohuslav Martinu, who was born in 1890, and finally, Mieczyslaw Weinberg, a Soviet composer of Polish-Jewish descent (he was known in the Soviet Union as Moisey Weinberg).

What we had so far is plenty already, but there are more anniversaries this week: the Spanish composer Joaquin Turina was born on the 9th, in 1882; César Franck – on the 10th of December, in 1822. The same day is the birthday of one of our favorite composers, Olivier Messiaen. Another Frenchman of immense talent, Hector Berlioz was born on December 11th of 1803. And finally, on the same day in 1908 Elliott Carter was born in Manhattan. Carter died in 2012, one month short of his 104th birthday. He wrote his last composition three months earlier. Carter is a seminal American composer and we’ll dedicate an entry to him alone sometime later. Right now, though, here’s his String Quartet No.5. It’s a difficult piece but very much worth the effort. It’s performed live by the Pacifica Quartet.Permalink