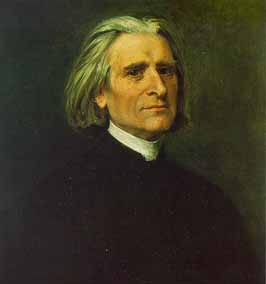

October 20, 2014.Franz Liszt.We’re marking the 113th birthday anniversary of the great Hungarian composer.Liszt was born on October 22nd of 1811 in a small village of Doborján (after the First World War that part of western Hungary was given to Austria; the town is now called Raiding).He grew up to become the greatest pianist of his time (and some believe of all time) and one of the most important composers of the 19th century.To celebrate, we‘re publishing an article by Joseph DuBose on the first of the three Années de pèlerinage piano suites,Première année: Suisse.We illustrate each piece (there are nine altogether in Première année) with performances by two young English pianists, Ashley Wass and Sodi Braide, both recorded in concerts, and two great Lisztians, the Cuban-American Jorge Bolet (1914 – 1990) and the Russian pianist Lazar Berman (1930 – 2005).The article follows. ♫

In early June 1835, Franz Liszt traveled from Paris to Switzerland. There, in Geneva, he met his mistress, Marie d’Agoult, who had recently left her husband and family for him. Over the next four years, they lived and journeyed throughout Switzerland and Italy. Inspired by the wondrous scenery of Switzerland and the rich cultural heritage of Italy, Liszt composed during these years a suite of piano pieces entitled Album d’un voyageur, a title which he likely adapted from that of a letter from George Sand: Lettre d’un voyageur. The suite was later published in 1842, after his relationship with d’Agoult had ended and he had returned to the life a touring virtuoso. However, Album would prove to be only the genesis of a much more significant collection of pieces. Between 1848 and 1854, Liszt revised several of its constituent pieces to form the first volume (Première année: Suisse) of his Années de pèlerinage (Years of Pilgrimage)—indeed, only two emerged relatively unaltered. Besides being personal reflections of Liszt’s travels, the pieces that ultimately became part of Première année were imbued with a keen sense of the Romantic literature of his time. The title of Années de pèlerinage itself is a certain reference to Goethe’s famous novel Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahr, but mostly significantly, its sequel Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahr, which in is first French translation was translated as “Years of Wanderings.” Furthermore, each piece was headed by quotations from Schiller, Byron, and Senancour, leading figures of the burgeoning Romantic Movement. The final result, Première Année: Suisse, was published in 1855. (Continue reading here.)

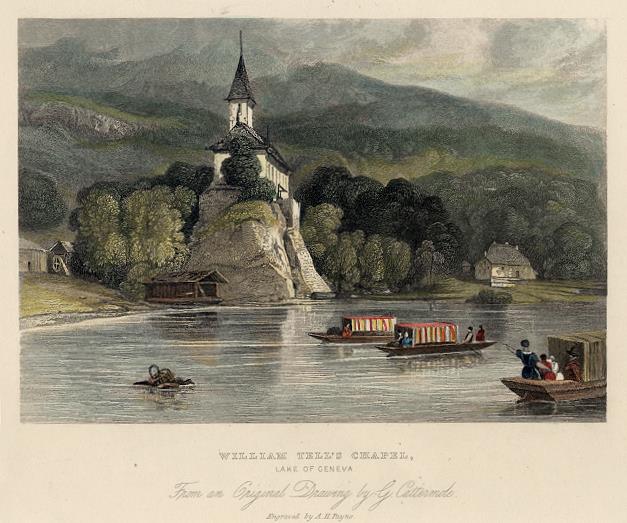

Opening Première Année is La Chapelle de Guillaume Tell (William Tell’s Chapel), here, is a bold and dramatic depiction of the legendary Swiss huntsman. The chapel itself from which the piece takes its name is on Lake Lucerne, and according to local tradition on the spot where Tell escaped from the bailiff Gessler. It is believed to have been constructed in 1388. However, the oldest recorded mention of the chapel is from the 16th century, when it became a popular place of pilgrimage. The current chapel was built in 1879, some forty years after Liszt’s visit. While his musical reflection of the visit is even prefaced with a line taken from Schiller’s play Wilhelm Tell (“All for one – one for all”), it nevertheless transcends the story of William Tell and embodies the universal conflict of man against tyranny. It opens defiantly with a bold choral subject in C major. In the central episode, “horn” calls ring out against a backdrop of dramatic tremolandi until the heroic struggle for freedom breaks forth in crisp dotted rhythms and a surging bass line beneath augmented sixth harmonies. Majestic, open fifths and a sweeping scale then announce the triumphant return of the choral subject, now embellished with harp-like chords. During the coda, the rising-third figure which had announced the first statement of the choral, returns intermixed with joyous horn calls. From a distant piano, the music grows into an exultant plagal cadence, embellished with resounding fanfares.

The second piece, Au Lac de Wallenstadt (“On Lake Walen”), here, Liszt headed with a quote taken from Lord Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage: “Thy contrasted lake / With the wild world I dwell in is a thing / Which warns me, with its stillness, to forsake / Earth's troubled waters for a purer spring.” The serene and picturesque lake in the Swiss Alps is here depicted by the rippling arpeggios of the accompaniment. Above, a peaceful melody of a simple construction sings out, and whose initial leaps upward of a perfect fifth and then a fourth instantly capture the vast calm of the lake and Byron’s “purer spring.” The rippling accompaniment remains a constant as the melody undergoes a modest development in E major and then an embellished reprise in the tonic of A-flat major. In the final bars, wide-spaced, harp-like chords replace the arpeggios while broken chords descending out of the upper register of the instrument bring the piece to a quiet and serene close.

Similar in character is the Pastorale, here, which along with the later Eglogue is one of two of the nine pieces of Première année not to reference a specific programmatic element, nor does it bare a literary quotation at its head. A fleeting Vivace, the piece alternates between two contrasting sections. The first is a lively melody in E major that proceeds mostly in sixths and thirds against bucolic, skipping fifths in the bass; the second is an even more vigorous ostinato-like subject in B major over drone fifths. Both section are repeated, with the second undergoing a slight embellishment. The dizzying figure of the latter subject swirls about the mediant, outlining a dominant harmony atop the tonic pedal in the bass, until it eventually exhausts itself of all energy by the time it closes on the tonic note.

One of the most popular pieces of Première année,Au bord d’un source (Beside a Spring) here, is also one of the more technically challenging. The picturesque scene of the piece is described in the quote taken from Schiller which Liszt chose to preface the piece: “In the whispering coolness begins young nature’s play.” As in Au Lac de Wallenstadt, the sound of water is here again imitated in the undercurrent of sixteenth notes that accompany the principal theme itself. An interesting feature of the accompaniment is the nearly ubiquitous seconds that its forms with the notes of the theme, which are later resolved as its characteristic pattern of broken chords unfolds. Furthermore, while the right hand manages these two contrasting lines, the left adds a further degree of technical difficulty with staccato notes that require it at times to leap over the active right hand. The piece is sectioned off into varied statements of the theme, creating the semblance of a quasi-variation form, and which are separated by brief, florid measures of passagework. Despite the technical demands made upon the performer during the successive variations, perhaps the most challenging is passing it all off in the calm, effortless manner required by the piece’s imagery. One of the pieces revised from his earlier Album d’un voyageur, Liszt produced a third version of Au bord d’un source in 1863 for one of his piano students, which replaced its serene ending with a virtuosic coda.

Turning to the key of C minor, Orage (Storm), here, unleashes upon the pastoral scenes of the previous four pieces all the raging fury of a mighty tempest. Prefacing the piece is a quote from Lord Byron, also taken from Child Harold’s Pilgrimage: “But where of ye, O tempests! is the goal? / Are ye like those within the human breast? / Or do ye find, at length, like eagles, some high nest?” Discords and vigorous passagework in octaves sets the stage for the Presto furioso principal theme, whose principal characteristic is a dramatic outlining of an augmented chord before resolving upwards to the tonic. After two statements, the theme is then played out across a sort of miniature sonata form, in which Liszt makes clever use of texture and harmony to depict the wild, raging storm. Thunder can be heard in both the furious accompaniment of octaves against the theme itself, and in the low-voiced discords that appear throughout the piece, which often include tritones, minor or major ninths, or even more bitter seconds. The howling wind is heard in the parallel first inversion chords that mark the beginning of the “development,” while lightening can easily be imagined in the brittle octaves or crisp chords heard in the upper register. A lengthy cadenza, dwelling on the opening gesture of the theme, precedes the theme’s full reprise. Briefly, the storm seems to lull as the music becomes quieter and eventually begins to dissipate in a passage of bare octaves. However, the tempest resumes, and a sweeping passage of scales doubled across four octaves brings the piece to its tempestuous close.

The sixth and longest piece of Première Année—it’s centerpiece, so to speak—is Vallée d’Obermann (The Valley of Obermann), here. The Valley, however, is not a real location is Switzerland, but a place invented by Senancour in which the protagonist Obermann, of his novel of the same name, finds solace from his weary life. Three quotes preface the work. Two are taken from Senancour’s novel of which one is Obermann’s defining question, “What do I want? Who am I? What do I ask of nature?” The other is once again from Byron: “Could I embody and unbosom now / That which is most within me,--could I wreak / My thoughts upon expression, and thus throw / Soul--heart--mind--passions--feelings--strong or weak-- / All that I would have sought, and all I seek, / Bear, know, feel--and yet breathe--into one word, / And that one word were Lightning, I would speak; / But as it is, I live and die unheard, / With a most voiceless thought, sheathing it as a sword." With the selection of the fictitious Valley of Obermann as subject matter, Liszt momentarily abandons the travelogue of his journey through Switzerland to embrace the purely metaphysical. The lugubrious tone of the work unfolds in the opening measures with a descending, syncopated figure, which becomes its principal motif, set against a poignant ninth chord. A more lyrical melody appears following the doleful introduction, yet its mood is no more the brighter as diminished triads in the accompaniment and appoggiaturas in the melody result in distressing diminished octaves. Following the close of the first section of the piece in E minor, the syncopated descending third becomes the main focus of the ensuing development. First transformed into a bittersweet melody in C major, it later reemerges in a tense Recitativo, and continues into an equally tumultuous section of dramatic tremolandi and terse, isolated thunderings in the bass. After a quasi-cadenza closes the development, the theme of the earlier C major section reappears in E major and forms the final section of the piece. Building into a florid climax of sweeping scales and brilliant, repeated chords, the joyful mood which struggles to emerge is suddenly undermined by the pull of the minor mode as the principal motif appears again in the bass. Managing to reach a brilliant tonic arpeggio, sounding much like a triumphant conclusion, a poignant and bitter fortissimo statement of the motif, brings the piece to an uneasy close.

Églogue (Eclogue), here, again takes its literary inspiration from Byron: “The morn is up again, the dewy morn, / With breath all incense, and with cheek all bloom, / Laughing the clouds away with playful scorn, / And living as if earth contained no tomb!" The gaiety of morning and liveliness of nature is here depicted in the rustic theme presented in the middle of the texture between a pedal point on the dominant in the highest voice and another on the tonic in the bass; then later in the playful motif of eighth notes that emerges out of chords of almost religious sanctity. After a repetition of the theme in the dominant, a new melody emerges over an accompaniment of eighth notes that wind their way around the submediant of A-flat major, and leads into a jocose passage in which its opening figure is playfully repeated in alternating loud and soft statements. This theme becomes the focus of much of the piece’s middle section, yet is intermixed with reminders of the opening melody. As the piece nears its end, Liszt unexpectedly sidesteps into A major before the pastoral scene fades away into a quiet close.

The penultimate piece of the suite, Le Mal du Pays (Homesickness), here, like the earlier Pastorale, lacks a literary reference. It begins with a doleful E minor melody twice statement in a lonely monophonic manner. Following the announcement of this melody is a quasi-fantasia section, which with various rhythms and melodic figurations alternates almost entirely between tonic and dominant harmonies. After coming to a half close in E minor and a lengthy pause of poignant silence, a new melody, just as melancholy as the previous, emerges in G-sharp minor. A brief moment of tenderness in the major mode, however, begins the melody’s second half, but soon after returns to the minor in which it ends. Liszt then repeats the early introduction and fantasia, now transposed in G minor. Following the pattern already established, the earlier G-sharp minor section now reappears in the key of B minor. The theme of this section, however, besides being somewhat varied, is also greatly expanded in an agitato section of severe loneliness and longing. Liszt ultimately reaches a warm restatement of the melody in E major. However, the closing measures returns to the minor mode. A last statement of the monophonic tune of the opening, now presented in the bass beneath alternating tonic and augmented sixth harmonies ends the piece with painful resignation.

The final piece, Les Cloches de Genève (The Bells of Geneva), here, was composed by Liszt in celebration of the birth of his and d’Agoult’s eldest daughter, who was born in the Swiss city. Prefaced by yet another quote from Byron (“I live not in myself, but I become / Portion of that around me”), this beautiful nocturne opens with imitations of bells in the triadic figurations that first appear by themselves in the introduction, then later accompany the lyrical Quasi allegretto melody. Between statements of the theme, Liszt interjects a remarkable passage imitating deep bell tones. Much of the piece, however, is contained within the beautiful Cantabile con moto section. Abandoning the compound meter of the opening and adopting a simple duple meter, the cantabile melody sings out above an accompaniment of descending arpeggios, pausing occasionally to break forth into brief, florid cadenzas. The music builds in affection until reaching a fortissimo statement marked con somma passione (“with great passion”). Culminating in sweeping arpeggios that span much of the keyboard, the music recedes into the quiet imitations of bells with which the piece opened, bringing the first volume of Années de pèlerinage to a peaceful close.

Franz Liszt, 2014

October 20, 2014. Franz Liszt. We’re marking the 113th birthday anniversary of the great Hungarian composer. Liszt was born on October 22nd of 1811 in a small village of Doborján (after the First World War that part of western Hungary was given to Austria; the town is now called Raiding). He grew up to become the greatest pianist of his time (and some believe of all time) and one of the most important composers of the 19th century. To celebrate, we‘re publishing an article by Joseph DuBose on the first of the three Années de pèlerinage piano suites, Première année: Suisse. We illustrate each piece (there are nine altogether in Première année) with performances by two young English pianists, Ashley Wass and Sodi Braide, both recorded in concerts, and two great Lisztians, the Cuban-American Jorge Bolet (1914 – 1990) and the Russian pianist Lazar Berman (1930 – 2005). The article follows. ♫

Raiding). He grew up to become the greatest pianist of his time (and some believe of all time) and one of the most important composers of the 19th century. To celebrate, we‘re publishing an article by Joseph DuBose on the first of the three Années de pèlerinage piano suites, Première année: Suisse. We illustrate each piece (there are nine altogether in Première année) with performances by two young English pianists, Ashley Wass and Sodi Braide, both recorded in concerts, and two great Lisztians, the Cuban-American Jorge Bolet (1914 – 1990) and the Russian pianist Lazar Berman (1930 – 2005). The article follows. ♫

In early June 1835, Franz Liszt traveled from Paris to Switzerland. There, in Geneva, he met his mistress, Marie d’Agoult, who had recently left her husband and family for him. Over the next four years, they lived and journeyed throughout Switzerland and Italy. Inspired by the wondrous scenery of Switzerland and the rich cultural heritage of Italy, Liszt composed during these years a suite of piano pieces entitled Album d’un voyageur, a title which he likely adapted from that of a letter from George Sand: Lettre d’un voyageur. The suite was later published in 1842, after his relationship with d’Agoult had ended and he had returned to the life a touring virtuoso. However, Album would prove to be only the genesis of a much more significant collection of pieces. Between 1848 and 1854, Liszt revised several of its constituent pieces to form the first volume (Première année: Suisse) of his Années de pèlerinage (Years of Pilgrimage)—indeed, only two emerged relatively unaltered. Besides being personal reflections of Liszt’s travels, the pieces that ultimately became part of Première année were imbued with a keen sense of the Romantic literature of his time. The title of Années de pèlerinage itself is a certain reference to Goethe’s famous novel Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahr, but mostly significantly, its sequel Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahr, which in is first French translation was translated as “Years of Wanderings.” Furthermore, each piece was headed by quotations from Schiller, Byron, and Senancour, leading figures of the burgeoning Romantic Movement. The final result, Première Année: Suisse, was published in 1855. (Continue reading here.)

Opening Première Année is La Chapelle de Guillaume Tell (William Tell’s Chapel), here, is a bold and dramatic depiction of the legendary Swiss huntsman. The chapel itself from which the piece takes its name is on Lake Lucerne, and according to local tradition on the spot where Tell escaped from the bailiff Gessler. It is believed to have been constructed in 1388. However, the oldest recorded mention of the chapel is from the 16th century, when it became a popular place of pilgrimage. The current chapel was built in 1879, some forty years after Liszt’s visit. While his musical reflection of the visit is even prefaced with a line taken from Schiller’s play Wilhelm Tell (“All for one – one for all”), it nevertheless transcends the story of William Tell and embodies the universal conflict of man against tyranny. It opens defiantly with a bold choral subject in C major. In the central episode, “horn” calls ring out against a backdrop of dramatic tremolandi until the heroic struggle for freedom breaks forth in crisp dotted rhythms and a surging bass line beneath augmented sixth harmonies. Majestic, open fifths and a sweeping scale then announce the triumphant return of the choral subject, now embellished with harp-like chords. During the coda, the rising-third figure which had announced the first statement of the choral, returns intermixed with joyous horn calls. From a distant piano, the music grows into an exultant plagal cadence, embellished with resounding fanfares.

name is on Lake Lucerne, and according to local tradition on the spot where Tell escaped from the bailiff Gessler. It is believed to have been constructed in 1388. However, the oldest recorded mention of the chapel is from the 16th century, when it became a popular place of pilgrimage. The current chapel was built in 1879, some forty years after Liszt’s visit. While his musical reflection of the visit is even prefaced with a line taken from Schiller’s play Wilhelm Tell (“All for one – one for all”), it nevertheless transcends the story of William Tell and embodies the universal conflict of man against tyranny. It opens defiantly with a bold choral subject in C major. In the central episode, “horn” calls ring out against a backdrop of dramatic tremolandi until the heroic struggle for freedom breaks forth in crisp dotted rhythms and a surging bass line beneath augmented sixth harmonies. Majestic, open fifths and a sweeping scale then announce the triumphant return of the choral subject, now embellished with harp-like chords. During the coda, the rising-third figure which had announced the first statement of the choral, returns intermixed with joyous horn calls. From a distant piano, the music grows into an exultant plagal cadence, embellished with resounding fanfares.

The second piece, Au Lac de Wallenstadt (“On Lake Walen”), here, Liszt headed with a quote taken from Lord Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage: “Thy contrasted lake / With the wild world I dwell in is a thing / Which warns me, with its stillness, to forsake / Earth's troubled waters for a purer spring.” The serene and picturesque lake in the Swiss Alps is here depicted by the rippling arpeggios of the accompaniment. Above, a peaceful melody of a simple construction sings out, and whose initial leaps upward of a perfect fifth and then a fourth instantly capture the vast calm of the lake and Byron’s “purer spring.” The rippling accompaniment remains a constant as the melody undergoes a modest development in E major and then an embellished reprise in the tonic of A-flat major. In the final bars, wide-spaced, harp-like chords replace the arpeggios while broken chords descending out of the upper register of the instrument bring the piece to a quiet and serene close.

a thing / Which warns me, with its stillness, to forsake / Earth's troubled waters for a purer spring.” The serene and picturesque lake in the Swiss Alps is here depicted by the rippling arpeggios of the accompaniment. Above, a peaceful melody of a simple construction sings out, and whose initial leaps upward of a perfect fifth and then a fourth instantly capture the vast calm of the lake and Byron’s “purer spring.” The rippling accompaniment remains a constant as the melody undergoes a modest development in E major and then an embellished reprise in the tonic of A-flat major. In the final bars, wide-spaced, harp-like chords replace the arpeggios while broken chords descending out of the upper register of the instrument bring the piece to a quiet and serene close.

Similar in character is the Pastorale, here, which along with the later Eglogue is one of two of the nine pieces of Première année not to reference a specific programmatic element, nor does it bare a literary quotation at its head. A fleeting Vivace, the piece alternates between two contrasting sections. The first is a lively melody in E major that proceeds mostly in sixths and thirds against bucolic, skipping fifths in the bass; the second is an even more vigorous ostinato-like subject in B major over drone fifths. Both section are repeated, with the second undergoing a slight embellishment. The dizzying figure of the latter subject swirls about the mediant, outlining a dominant harmony atop the tonic pedal in the bass, until it eventually exhausts itself of all energy by the time it closes on the tonic note.

One of the most popular pieces of Première année, Au bord d’un source (Beside a Spring) here, is also one of the more technically challenging. The picturesque scene of the piece is described in the quote taken from Schiller which Liszt chose to preface the piece: “In the whispering coolness begins young nature’s play.” As in Au Lac de Wallenstadt, the sound of water is here again imitated in the undercurrent of sixteenth notes that accompany the principal theme itself. An interesting feature of the accompaniment is the nearly ubiquitous seconds that its forms with the notes of the theme, which are later resolved as its characteristic pattern of broken chords unfolds. Furthermore, while the right hand manages these two contrasting lines, the left adds a further degree of technical difficulty with staccato notes that require it at times to leap over the active right hand. The piece is sectioned off into varied statements of the theme, creating the semblance of a quasi-variation form, and which are separated by brief, florid measures of passagework. Despite the technical demands made upon the performer during the successive variations, perhaps the most challenging is passing it all off in the calm, effortless manner required by the piece’s imagery. One of the pieces revised from his earlier Album d’un voyageur, Liszt produced a third version of Au bord d’un source in 1863 for one of his piano students, which replaced its serene ending with a virtuosic coda.

Turning to the key of C minor, Orage (Storm), here, unleashes upon the pastoral scenes of the previous four pieces all the raging fury of a mighty tempest. Prefacing the piece is a quote from Lord Byron, also taken from Child Harold’s Pilgrimage: “But where of ye, O tempests! is the goal? / Are ye like those within the human breast? / Or do ye find, at length, like eagles, some high nest?” Discords and vigorous passagework in octaves sets the stage for the Presto furioso principal theme, whose principal characteristic is a dramatic outlining of an augmented chord before resolving upwards to the tonic. After two statements, the theme is then played out across a sort of miniature sonata form, in which Liszt makes clever use of texture and harmony to depict the wild, raging storm. Thunder can be heard in both the furious accompaniment of octaves against the theme itself, and in the low-voiced discords that appear throughout the piece, which often include tritones, minor or major ninths, or even more bitter seconds. The howling wind is heard in the parallel first inversion chords that mark the beginning of the “development,” while lightening can easily be imagined in the brittle octaves or crisp chords heard in the upper register. A lengthy cadenza, dwelling on the opening gesture of the theme, precedes the theme’s full reprise. Briefly, the storm seems to lull as the music becomes quieter and eventually begins to dissipate in a passage of bare octaves. However, the tempest resumes, and a sweeping passage of scales doubled across four octaves brings the piece to its tempestuous close.

The sixth and longest piece of Première Année—it’s centerpiece, so to speak—is Vallée d’Obermann (The Valley of Obermann), here. The Valley, however, is not a real location is Switzerland, but a place.jpg) invented by Senancour in which the protagonist Obermann, of his novel of the same name, finds solace from his weary life. Three quotes preface the work. Two are taken from Senancour’s novel of which one is Obermann’s defining question, “What do I want? Who am I? What do I ask of nature?” The other is once again from Byron: “Could I embody and unbosom now / That which is most within me,--could I wreak / My thoughts upon expression, and thus throw / Soul--heart--mind--passions--feelings--strong or weak-- / All that I would have sought, and all I seek, / Bear, know, feel--and yet breathe--into one word, / And that one word were Lightning, I would speak; / But as it is, I live and die unheard, / With a most voiceless thought, sheathing it as a sword." With the selection of the fictitious Valley of Obermann as subject matter, Liszt momentarily abandons the travelogue of his journey through Switzerland to embrace the purely metaphysical. The lugubrious tone of the work unfolds in the opening measures with a descending, syncopated figure, which becomes its principal motif, set against a poignant ninth chord. A more lyrical melody appears following the doleful introduction, yet its mood is no more the brighter as diminished triads in the accompaniment and appoggiaturas in the melody result in distressing diminished octaves. Following the close of the first section of the piece in E minor, the syncopated descending third becomes the main focus of the ensuing development. First transformed into a bittersweet melody in C major, it later reemerges in a tense Recitativo, and continues into an equally tumultuous section of dramatic tremolandi and terse, isolated thunderings in the bass. After a quasi-cadenza closes the development, the theme of the earlier C major section reappears in E major and forms the final section of the piece. Building into a florid climax of sweeping scales and brilliant, repeated chords, the joyful mood which struggles to emerge is suddenly undermined by the pull of the minor mode as the principal motif appears again in the bass. Managing to reach a brilliant tonic arpeggio, sounding much like a triumphant conclusion, a poignant and bitter fortissimo statement of the motif, brings the piece to an uneasy close.

invented by Senancour in which the protagonist Obermann, of his novel of the same name, finds solace from his weary life. Three quotes preface the work. Two are taken from Senancour’s novel of which one is Obermann’s defining question, “What do I want? Who am I? What do I ask of nature?” The other is once again from Byron: “Could I embody and unbosom now / That which is most within me,--could I wreak / My thoughts upon expression, and thus throw / Soul--heart--mind--passions--feelings--strong or weak-- / All that I would have sought, and all I seek, / Bear, know, feel--and yet breathe--into one word, / And that one word were Lightning, I would speak; / But as it is, I live and die unheard, / With a most voiceless thought, sheathing it as a sword." With the selection of the fictitious Valley of Obermann as subject matter, Liszt momentarily abandons the travelogue of his journey through Switzerland to embrace the purely metaphysical. The lugubrious tone of the work unfolds in the opening measures with a descending, syncopated figure, which becomes its principal motif, set against a poignant ninth chord. A more lyrical melody appears following the doleful introduction, yet its mood is no more the brighter as diminished triads in the accompaniment and appoggiaturas in the melody result in distressing diminished octaves. Following the close of the first section of the piece in E minor, the syncopated descending third becomes the main focus of the ensuing development. First transformed into a bittersweet melody in C major, it later reemerges in a tense Recitativo, and continues into an equally tumultuous section of dramatic tremolandi and terse, isolated thunderings in the bass. After a quasi-cadenza closes the development, the theme of the earlier C major section reappears in E major and forms the final section of the piece. Building into a florid climax of sweeping scales and brilliant, repeated chords, the joyful mood which struggles to emerge is suddenly undermined by the pull of the minor mode as the principal motif appears again in the bass. Managing to reach a brilliant tonic arpeggio, sounding much like a triumphant conclusion, a poignant and bitter fortissimo statement of the motif, brings the piece to an uneasy close.

Églogue (Eclogue), here, again takes its literary inspiration from Byron: “The morn is up again, the dewy morn, / With breath all incense, and with cheek all bloom, / Laughing the clouds away with playful scorn, / And living as if earth contained no tomb!" The gaiety of morning and liveliness of nature is here depicted in the rustic theme presented in the middle of the texture between a pedal point on the dominant in the highest voice and another on the tonic in the bass; then later in the playful motif of eighth notes that emerges out of chords of almost religious sanctity. After a repetition of the theme in the dominant, a new melody emerges over an accompaniment of eighth notes that wind their way around the submediant of A-flat major, and leads into a jocose passage in which its opening figure is playfully repeated in alternating loud and soft statements. This theme becomes the focus of much of the piece’s middle section, yet is intermixed with reminders of the opening melody. As the piece nears its end, Liszt unexpectedly sidesteps into A major before the pastoral scene fades away into a quiet close.

The penultimate piece of the suite, Le Mal du Pays (Homesickness), here, like the earlier Pastorale, lacks a literary reference. It begins with a doleful E minor melody twice statement in a lonely monophonic manner. Following the announcement of this melody is a quasi-fantasia section, which with various rhythms and melodic figurations alternates almost entirely between tonic and dominant harmonies. After coming to a half close in E minor and a lengthy pause of poignant silence, a new melody, just as melancholy as the previous, emerges in G-sharp minor. A brief moment of tenderness in the major mode, however, begins the melody’s second half, but soon after returns to the minor in which it ends. Liszt then repeats the early introduction and fantasia, now transposed in G minor. Following the pattern already established, the earlier G-sharp minor section now reappears in the key of B minor. The theme of this section, however, besides being somewhat varied, is also greatly expanded in an agitato section of severe loneliness and longing. Liszt ultimately reaches a warm restatement of the melody in E major. However, the closing measures returns to the minor mode. A last statement of the monophonic tune of the opening, now presented in the bass beneath alternating tonic and augmented sixth harmonies ends the piece with painful resignation.

The final piece, Les Cloches de Genève (The Bells of Geneva), here, was composed by Liszt in celebration of the birth of his and d’Agoult’s eldest daughter, who was born in the Swiss city. Prefaced by yet another quote from Byron (“I live not in myself, but I become / Portion of that around me”), this beautiful nocturne opens with imitations of bells in the triadic figurations that first appear by themselves in the introduction, then later accompany the lyrical Quasi allegretto melody. Between statements of the theme, Liszt interjects a remarkable passage imitating deep bell tones. Much of the piece, however, is contained within the beautiful Cantabile con moto section. Abandoning the compound meter of the opening and adopting a simple duple meter, the cantabile melody sings out above an accompaniment of descending arpeggios, pausing occasionally to break forth into brief, florid cadenzas. The music builds in affection until reaching a fortissimo statement marked con somma passione (“with great passion”). Culminating in sweeping arpeggios that span much of the keyboard, the music recedes into the quiet imitations of bells with which the piece opened, bringing the first volume of Années de pèlerinage to a peaceful close.

yet another quote from Byron (“I live not in myself, but I become / Portion of that around me”), this beautiful nocturne opens with imitations of bells in the triadic figurations that first appear by themselves in the introduction, then later accompany the lyrical Quasi allegretto melody. Between statements of the theme, Liszt interjects a remarkable passage imitating deep bell tones. Much of the piece, however, is contained within the beautiful Cantabile con moto section. Abandoning the compound meter of the opening and adopting a simple duple meter, the cantabile melody sings out above an accompaniment of descending arpeggios, pausing occasionally to break forth into brief, florid cadenzas. The music builds in affection until reaching a fortissimo statement marked con somma passione (“with great passion”). Culminating in sweeping arpeggios that span much of the keyboard, the music recedes into the quiet imitations of bells with which the piece opened, bringing the first volume of Années de pèlerinage to a peaceful close.