May 18, 2015.Wagner’s Tannhäuser.Richard Wagner was born on May 22nd of 1813.Somehow, this date seems incongruous: was he really just three years younger than Chopin and Schumann?Those are geniuses firmly established in the Pantheon of classical music, while people still argue about Wagner.His music and his writings still can create controversies, as we’ll see in a minute.Wagner was living in Paris when he completed his third and fourth operas, Rienzi and The Flying Dutchman.He approached Giacomo Meyerbeer, a German-Jewish composer who was living in Paris and asked for advice on the staging of Rienzi.Wagner’s letters to Meyerbeer sound almost obsequious, which is worth noticing, considering the events that followed.In the previous decade Meyerbeer had conquered Paris with his own operas, Robert le Diable in particular.Even though he had lived in Paris for many years, Meyerbeer still maintained connections in Germany, which he used to help Wagner, in Dresden with Rienzi and in Berlin with The Flying Dutchman.In 1842 Rienzi was accepted at the Dresden Court Theater and Wagner moved there right away.The opera was premiered in October of that year and proved to be a success, Wagner’s first.A couple years later he was appointed the conductor at the Court Theater.Wagner, whom Meyerbeer not only helped at a critical moment of Wagner’s life, but who also deeply influenced him by his operas, eventually became Meyerbeer’s biggest enemy.He wrote several pamphlets against Meyerbeer, all of them deeply anti-Semitic in nature.But that was to come later.While still in Dresden, Wagner wrote Tannhäuser, an opera on his own libretto, derived from German legends about a 13th-century German minnesinger Henrich Tannhäuser and a certain song contest.Long, convoluted, and at times incoherent, it tells a story of the poet and singer Tannhäuser who lives in the realm of Venus, the goddess of love, surrounded by young beautiful women.After some sexual shenanigans he decides that he’s had enough and returns to real life in Wartburg.There, the local count holds a song contest.Tannhäuser’s love song is considered too profane and he’s banished from Wartburg and ordered to visit the Pope.More fantastic events take place, involving Tannhäuser, his love interest Elisabeth, and his friend Wolfram, with Venus making an appearance and the Pope’s staff flowering at the very end of the opera.None of it makes much sense, but the juxtaposition of Venus and the church, of lust, love and faith gives directors ample opportunity to excersize their fantazy.Modern productions set Tannhäuser in different eras and some use a good doze of nudity and profanity. One such production, rather mild by European standards, was recently created in the Russian city of Novosibirsk.What followed was a rather typical Russian story.The hierarchs of the local Orthodox church rose in protest, and so did the more conservative members of the local society.Demonstrations were staged, accusations were hurled in the media, the courts got involved.And even though some members of the Russian artistic community tried (rather meekly, it has to be said) to defend the production, the minister of culture moved in and sacked the director.Truly, modern Russia is more bizarre than any of Wagner’s librettos.

All of this doesn’t really matter: the music of Tannhäuser is great, and gets better as the opera evolves.The third act is magnificent.Here’s an excerpt, with the great German baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, the orchestra of Staatsoper Berlin, Franz Konwitschny conducting.

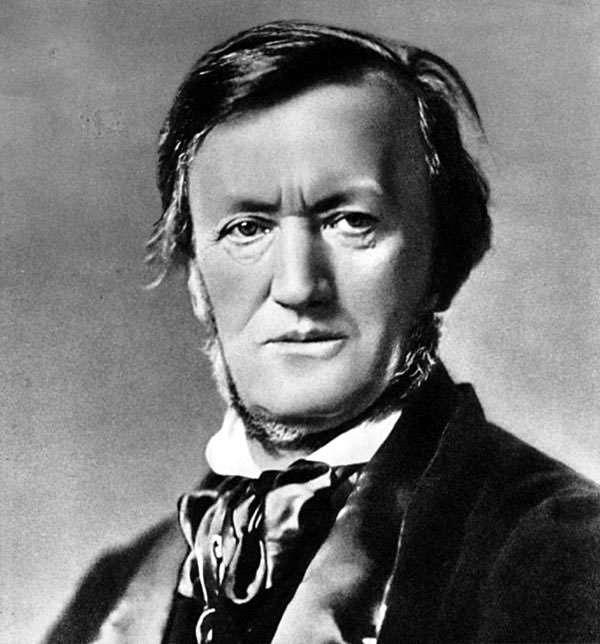

Wagner 2015

May 18, 2015. Wagner’s Tannhäuser. Richard Wagner was born on May 22nd of 1813. Somehow, this date seems incongruous: was he really just three years younger than Chopin and Schumann? Those are geniuses firmly established in the Pantheon of classical music, while people still argue about Wagner. His music and his writings still can create controversies, as we’ll see in a minute. Wagner was living in Paris when he completed his third and fourth operas, Rienzi and The Flying Dutchman. He approached Giacomo Meyerbeer, a German-Jewish composer who was living in Paris and asked for advice on the staging of Rienzi. Wagner’s letters to Meyerbeer sound almost obsequious, which is worth noticing, considering the events that followed. In the previous decade Meyerbeer had conquered Paris with his own operas, Robert le Diable in particular. Even though he had lived in Paris for many years, Meyerbeer still maintained connections in Germany, which he used to help Wagner, in Dresden with Rienzi and in Berlin with The Flying Dutchman. In 1842 Rienzi was accepted at the Dresden Court Theater and Wagner moved there right away. The opera was premiered in October of that year and proved to be a success, Wagner’s first. A couple years later he was appointed the conductor at the Court Theater. Wagner, whom Meyerbeer not only helped at a critical moment of Wagner’s life, but who also deeply influenced him by his operas, eventually became Meyerbeer’s biggest enemy. He wrote several pamphlets against Meyerbeer, all of them deeply anti-Semitic in nature. But that was to come later. While still in Dresden, Wagner wrote Tannhäuser, an opera on his own libretto, derived from German legends about a 13th-century German minnesinger Henrich Tannhäuser and a certain song contest. Long, convoluted, and at times incoherent, it tells a story of the poet and singer Tannhäuser who lives in the realm of Venus, the goddess of love, surrounded by young beautiful women. After some sexual shenanigans he decides that he’s had enough and returns to real life in Wartburg. There, the local count holds a song contest. Tannhäuser’s love song is considered too profane and he’s banished from Wartburg and ordered to visit the Pope. More fantastic events take place, involving Tannhäuser, his love interest Elisabeth, and his friend Wolfram, with Venus making an appearance and the Pope’s staff flowering at the very end of the opera. None of it makes much sense, but the juxtaposition of Venus and the church, of lust, love and faith gives directors ample opportunity to excersize their fantazy. Modern productions set Tannhäuser in different eras and some use a good doze of nudity and profanity. One such production, rather mild by European standards, was recently created in the Russian city of Novosibirsk. What followed was a rather typical Russian story. The hierarchs of the local Orthodox church rose in protest, and so did the more conservative members of the local society. Demonstrations were staged, accusations were hurled in the media, the courts got involved. And even though some members of the Russian artistic community tried (rather meekly, it has to be said) to defend the production, the minister of culture moved in and sacked the director. Truly, modern Russia is more bizarre than any of Wagner’s librettos.

when he completed his third and fourth operas, Rienzi and The Flying Dutchman. He approached Giacomo Meyerbeer, a German-Jewish composer who was living in Paris and asked for advice on the staging of Rienzi. Wagner’s letters to Meyerbeer sound almost obsequious, which is worth noticing, considering the events that followed. In the previous decade Meyerbeer had conquered Paris with his own operas, Robert le Diable in particular. Even though he had lived in Paris for many years, Meyerbeer still maintained connections in Germany, which he used to help Wagner, in Dresden with Rienzi and in Berlin with The Flying Dutchman. In 1842 Rienzi was accepted at the Dresden Court Theater and Wagner moved there right away. The opera was premiered in October of that year and proved to be a success, Wagner’s first. A couple years later he was appointed the conductor at the Court Theater. Wagner, whom Meyerbeer not only helped at a critical moment of Wagner’s life, but who also deeply influenced him by his operas, eventually became Meyerbeer’s biggest enemy. He wrote several pamphlets against Meyerbeer, all of them deeply anti-Semitic in nature. But that was to come later. While still in Dresden, Wagner wrote Tannhäuser, an opera on his own libretto, derived from German legends about a 13th-century German minnesinger Henrich Tannhäuser and a certain song contest. Long, convoluted, and at times incoherent, it tells a story of the poet and singer Tannhäuser who lives in the realm of Venus, the goddess of love, surrounded by young beautiful women. After some sexual shenanigans he decides that he’s had enough and returns to real life in Wartburg. There, the local count holds a song contest. Tannhäuser’s love song is considered too profane and he’s banished from Wartburg and ordered to visit the Pope. More fantastic events take place, involving Tannhäuser, his love interest Elisabeth, and his friend Wolfram, with Venus making an appearance and the Pope’s staff flowering at the very end of the opera. None of it makes much sense, but the juxtaposition of Venus and the church, of lust, love and faith gives directors ample opportunity to excersize their fantazy. Modern productions set Tannhäuser in different eras and some use a good doze of nudity and profanity. One such production, rather mild by European standards, was recently created in the Russian city of Novosibirsk. What followed was a rather typical Russian story. The hierarchs of the local Orthodox church rose in protest, and so did the more conservative members of the local society. Demonstrations were staged, accusations were hurled in the media, the courts got involved. And even though some members of the Russian artistic community tried (rather meekly, it has to be said) to defend the production, the minister of culture moved in and sacked the director. Truly, modern Russia is more bizarre than any of Wagner’s librettos.

All of this doesn’t really matter: the music of Tannhäuser is great, and gets better as the opera evolves. The third act is magnificent. Here’s an excerpt, with the great German baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, the orchestra of Staatsoper Berlin, Franz Konwitschny conducting.