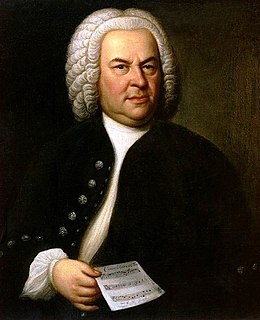

March 19, 2018.Bach and Richter.In two days we’ll celebrate Johann Sebastian Bach’s 333rd birthday.We’ve written about Bach’s early years in Leipzig (here and here), the years that were dedicated to his work as the Kantor at Tomasschule, the school of the St. Thomas church, wherehe also served as the choir director.All along Bach was the music director of two other important churches in the city, St. Nicholas church (Nikolaikirche) and Paulinerkirche, the University church.His duties included writing music for Sunday services, and in the early Leipzig years he produced an astonishing number of cantatas, more than 300 altogether, of which 200 plus are extant.He also wrote several Passions, of which the St. John’s and St. Matthew survive.By the year 1729 the accumulated volume of compositions was such that he could allow himself to either perform the old music, or reuse pre-existing material, creating what is called “parody” cantatas.(The old and rather unusual musical term “parody,” or imitation, has nothing to do with humor.“Parody mass,” for example, was one of the major types of Renaissance mass where the composer used – and acknowledged – the borrowed material.The intellectual property rules were very vague in those days).By the year 1729, Bach’s creative forces shifted away from church music to secular music. One impetus was Collegium Musicum, of which Bach was appointed the director in 1729.Collegium Musicum was created by Telemann in 1702 as an association of professional musicians and students for the purpose of producing regular public concerts.During the winter the concerts were given at Café Zimmermann, one of the largest coffee houses in Leipzig (the building was constructed in 1715; it was destroyed during the Allied air raid in 1943).Bach’s Coffee Cantata, BWV 211, was probably premiered at Zimmermann’s.Several of Bach’s keyboard and violin concertos were written for Collegium Musicum.It’s quite likely that Wilhelm Friedemann and Carl Philipp Emanuel, two of Bach’s sons, performed with the Collegium.

Bach also continued writing keyboard pieces.Those were published in four books called Clavier-Übung, or keyboard exercise.The first volume, published in 1731, contained six partitas for harpsichord, the second, in 1735 – two pieces, the Italian Concerto BWV 971 and Overture in the French style, BWV 831.You can hear the Italian Concerto here, and the Overture – here.Both are performed by Sviatoslav Richter; the recordings were made in 1991, when Richter was 76.

One of the greatest pianists of the 20th century, Sviatoslav Richter was born on March 20th of 1915 in Zhitomir, Ukraine.His father, Teofil Richter, was a pianist and a German expat, his mother was Russian.The family moved to Odessa in 1921.Even though Teofil taught at the Conservatory, little Sviatoslav studied music mostly on his own.At the age of 15 he started working at the local opera as a rehearsal pianist.Without any further formal education, he auditioned for Heinrich Neuhaus at the Moscow Conservatory in 1937.Neuhaus, who had the strongest class in all of the Conservatory (Emil Gilels and Radu Lupu were his students), accepted him immediately.Richter’s studies didn’t last long, though: he wouldn’t attend the non-music classes, was kicked out after several months and returned to Odessa.Neuhaus, who considered his pupil a genius, insisted that he return.Richter was re-admitted but got his official diploma only in 1947.That didn’t stop him from playing concerts: in 1940 he premiered Prokofiev’s Sixth Piano sonata, then played his first Moscow concert with the orchestra.As Germany attacked Russia in 1941, Sviatoslav’s life, as that of every other Soviet citizen, changed forever.His father, as so many Russian Germans, was arrested and later executed.His mother disappeared and was presumed dead; only many years later would Sviatoslav find out that she eventually made it to Germany.To be continued next week.

Bach and Richter, 2018

March 19, 2018. Bach and Richter. In two days we’ll celebrate Johann Sebastian Bach’s 333rd birthday. We’ve written about Bach’s early years in Leipzig (here and here), the years that were dedicated to his work as the Kantor at Tomasschule, the school of the St. Thomas church, wherehe also served as the choir director. All along Bach was the music director of two other important churches in the city, St. Nicholas church (Nikolaikirche) and Paulinerkirche, the University church. His duties included writing music for Sunday services, and in the early Leipzig years he produced an astonishing number of cantatas, more than 300 altogether, of which 200 plus are extant. He also wrote several Passions, of which the St. John’s and St. Matthew survive. By the year 1729 the accumulated volume of compositions was such that he could allow himself to either perform the old music, or reuse pre-existing material, creating what is called “parody” cantatas. (The old and rather unusual musical term “parody,” or imitation, has nothing to do with humor. “Parody mass,” for example, was one of the major types of Renaissance mass where the composer used – and acknowledged – the borrowed material. The intellectual property rules were very vague in those days). By the year 1729, Bach’s creative forces shifted away from church music to secular music. One impetus was Collegium Musicum, of which Bach was appointed the director in 1729. Collegium Musicum was created by Telemann in 1702 as an association of professional musicians and students for the purpose of producing regular public concerts. During the winter the concerts were given at Café Zimmermann, one of the largest coffee houses in Leipzig (the building was constructed in 1715; it was destroyed during the Allied air raid in 1943). Bach’s Coffee Cantata, BWV 211, was probably premiered at Zimmermann’s. Several of Bach’s keyboard and violin concertos were written for Collegium Musicum. It’s quite likely that Wilhelm Friedemann and Carl Philipp Emanuel, two of Bach’s sons, performed with the Collegium.

important churches in the city, St. Nicholas church (Nikolaikirche) and Paulinerkirche, the University church. His duties included writing music for Sunday services, and in the early Leipzig years he produced an astonishing number of cantatas, more than 300 altogether, of which 200 plus are extant. He also wrote several Passions, of which the St. John’s and St. Matthew survive. By the year 1729 the accumulated volume of compositions was such that he could allow himself to either perform the old music, or reuse pre-existing material, creating what is called “parody” cantatas. (The old and rather unusual musical term “parody,” or imitation, has nothing to do with humor. “Parody mass,” for example, was one of the major types of Renaissance mass where the composer used – and acknowledged – the borrowed material. The intellectual property rules were very vague in those days). By the year 1729, Bach’s creative forces shifted away from church music to secular music. One impetus was Collegium Musicum, of which Bach was appointed the director in 1729. Collegium Musicum was created by Telemann in 1702 as an association of professional musicians and students for the purpose of producing regular public concerts. During the winter the concerts were given at Café Zimmermann, one of the largest coffee houses in Leipzig (the building was constructed in 1715; it was destroyed during the Allied air raid in 1943). Bach’s Coffee Cantata, BWV 211, was probably premiered at Zimmermann’s. Several of Bach’s keyboard and violin concertos were written for Collegium Musicum. It’s quite likely that Wilhelm Friedemann and Carl Philipp Emanuel, two of Bach’s sons, performed with the Collegium.

Bach also continued writing keyboard pieces. Those were published in four books called Clavier-Übung, or keyboard exercise. The first volume, published in 1731, contained six partitas for harpsichord, the second, in 1735 – two pieces, the Italian Concerto BWV 971 and Overture in the French style, BWV 831. You can hear the Italian Concerto here, and the Overture – here. Both are performed by Sviatoslav Richter; the recordings were made in 1991, when Richter was 76.

One of the greatest pianists of the 20th century, Sviatoslav Richter was born on March 20th of 1915 in Zhitomir, Ukraine. His father, Teofil Richter, was a pianist and a German expat, his mother was Russian. The family moved to Odessa in 1921. Even though Teofil taught at the Conservatory, little Sviatoslav studied music mostly on his own. At the age of 15 he started working at the local opera as a rehearsal pianist. Without any further formal education, he auditioned for Heinrich Neuhaus at the Moscow Conservatory in 1937. Neuhaus, who had the strongest class in all of the Conservatory (Emil Gilels and Radu Lupu were his students), accepted him immediately. Richter’s studies didn’t last long, though: he wouldn’t attend the non-music classes, was kicked out after several months and returned to Odessa. Neuhaus, who considered his pupil a genius, insisted that he return. Richter was re-admitted but got his official diploma only in 1947. That didn’t stop him from playing concerts: in 1940 he premiered Prokofiev’s Sixth Piano sonata, then played his first Moscow concert with the orchestra. As Germany attacked Russia in 1941, Sviatoslav’s life, as that of every other Soviet citizen, changed forever. His father, as so many Russian Germans, was arrested and later executed. His mother disappeared and was presumed dead; only many years later would Sviatoslav find out that she eventually made it to Germany. To be continued next week.