April 3, 2018.Haydn, Pogorelich.We’d like to come back to Joseph Haydn, whom we mentioned, rather perfunctorily, last week.As we were looking for a sample of Richter’s recording of a Haydn sonata (Richter made several and played Haydn often) we came across one made by Ivo Pogorelich in 1991.It was a recording of a wonderful Piano Sonata no. 30 in D major, Hoboken XVI:19, composed in 1767.Pogorelich, born in Belgrade, is one of the most unusual pianists of his generation.His career began with a scandal: in 1980 the jury of the Chopin International Competition eliminated him after the second round.Martha Argerich resigned in protest (she was not the only one to object, so did Nikita Magaloff and Paul Badura-Skoda, although they didn’t quit).The publicity generated by the Warsaw scandal helped Pogorelich’s career.While some of his interpretations were eccentric, they were not outlandish, on top of which he had a flawless technique.In 1981 Pogorelich was invited to the Carnegie Hall (he played there many times; his 1992 performance of Balakirev’s Islamey became legendary).That same year, 1981, he debuted in London, and a year later he was signed by Deutsche Grammophon.Pogorelich had studied in the Soviet Union since 1976; the year of the Chopin Competition he married his teacher, Alisa Kezheradze, 21 years his senior. Little is known about Kezheradze.When she met Pogorelich, she was married to a Soviet functionary, living in a large apartment in the center of Moscow.She taught piano at the Music department of the Pedagogic Institute (Vladimir Genis, a Russian-German composer and pianist who studied there, remembers Kezheradze as “the only bright spot in that theater of the absurd, … striking, slim, of indeterminate age, with a face of a Georgian princess.”

She also worked with several Conservatory students.One of them was the young Mikhail Pletnev, whom Kezheradze prepared for the 1978 Tchaikovsky Competition after the death of Pletnev’s professor, Yakov Flier, six months earlier.Pletnev went on to win the competition.By then Kezheradze had already divorced her first husband.Her and Ivos’ marriage application was first rejected, but later the authorities relented, allowing them to marry and emigrate.Kezheradze and Pogorelich moved to Europe where they lived together till her death of liver cancer in 1996.Pogorelich, devastated by the loss, practically abandoned the concert stage. When, some years later, he resumed his public career, the eccentricities of his earlier years developed into interpretations that were often incomprehensible.He took the tempos so slow that the whole musical structure fell apart (for example, his recording of Chopin’s Nocturne op. 48, no. 1 takes an insane but mesmerizing nine minutes and ten seconds.Arthur Rubinstein plays it, stately, in a 5:47).He’d play either pianissimo or fortissimo, with strange accents.Anthony Tommasini of the New York Time finished his 2006 review of a Carnegie Hall concert thusly: "Here is an immense talent gone tragically astray. What went wrong?"It’s impossible to answer this question, but there are many of Pogorelich’s recordings that could be enjoyed today.The Hob. XVI:19 is one of them.Every one of Haydn’s musical ideas is brilliantly enunciated, every line is clear, the sound is beautiful, everything is balanced – a great performance overall.Listen to it here.

Haydn and Pogorelich

April 3, 2018. Haydn, Pogorelich. We’d like to come back to Joseph Haydn, whom we mentioned, rather perfunctorily, last week. As we were looking for a sample of Richter’s recording of a Haydn sonata (Richter made several and played Haydn often) we came across one made by Ivo Pogorelich in 1991. It was a recording of a wonderful Piano Sonata no. 30 in D major, Hoboken XVI:19, composed in 1767. Pogorelich, born in Belgrade, is one of the most unusual pianists of his generation. His career began with a scandal: in 1980 the jury of the Chopin International Competition eliminated him after the second round. Martha Argerich resigned in protest (she was not the only one to object, so did Nikita Magaloff and Paul Badura-Skoda, although they didn’t quit). The publicity generated by the Warsaw scandal helped Pogorelich’s career. While some of his interpretations were eccentric, they were not outlandish, on top of which he had a flawless technique. In 1981 Pogorelich was invited to the Carnegie Hall (he played there many times; his 1992 performance of Balakirev’s Islamey became legendary). That same year, 1981, he debuted in London, and a year later he was signed by Deutsche Grammophon. Pogorelich had studied in the Soviet Union since 1976; the year of the Chopin Competition he married his teacher, Alisa Kezheradze, 21 years his senior. Little is known about Kezheradze. When she met Pogorelich, she was married to a Soviet functionary, living in a large apartment in the center of Moscow. She taught piano at the Music department of the Pedagogic Institute (Vladimir Genis, a Russian-German composer and pianist who studied there, remembers Kezheradze as “the only bright spot in that theater of the absurd, … striking, slim, of indeterminate age, with a face of a Georgian princess.”

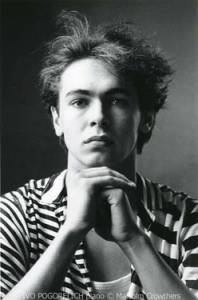

Pogorelich in 1991. It was a recording of a wonderful Piano Sonata no. 30 in D major, Hoboken XVI:19, composed in 1767. Pogorelich, born in Belgrade, is one of the most unusual pianists of his generation. His career began with a scandal: in 1980 the jury of the Chopin International Competition eliminated him after the second round. Martha Argerich resigned in protest (she was not the only one to object, so did Nikita Magaloff and Paul Badura-Skoda, although they didn’t quit). The publicity generated by the Warsaw scandal helped Pogorelich’s career. While some of his interpretations were eccentric, they were not outlandish, on top of which he had a flawless technique. In 1981 Pogorelich was invited to the Carnegie Hall (he played there many times; his 1992 performance of Balakirev’s Islamey became legendary). That same year, 1981, he debuted in London, and a year later he was signed by Deutsche Grammophon. Pogorelich had studied in the Soviet Union since 1976; the year of the Chopin Competition he married his teacher, Alisa Kezheradze, 21 years his senior. Little is known about Kezheradze. When she met Pogorelich, she was married to a Soviet functionary, living in a large apartment in the center of Moscow. She taught piano at the Music department of the Pedagogic Institute (Vladimir Genis, a Russian-German composer and pianist who studied there, remembers Kezheradze as “the only bright spot in that theater of the absurd, … striking, slim, of indeterminate age, with a face of a Georgian princess.”

She also worked with several Conservatory students. One of them was the young Mikhail Pletnev, whom Kezheradze prepared for the 1978 Tchaikovsky Competition after the death of Pletnev’s professor, Yakov Flier, six months earlier. Pletnev went on to win the competition. By then Kezheradze had already divorced her first husband. Her and Ivos’ marriage application was first rejected, but later the authorities relented, allowing them to marry and emigrate. Kezheradze and Pogorelich moved to Europe where they lived together till her death of liver cancer in 1996. Pogorelich, devastated by the loss, practically abandoned the concert stage. When, some years later, he resumed his public career, the eccentricities of his earlier years developed into interpretations that were often incomprehensible. He took the tempos so slow that the whole musical structure fell apart (for example, his recording of Chopin’s Nocturne op. 48, no. 1 takes an insane but mesmerizing nine minutes and ten seconds. Arthur Rubinstein plays it, stately, in a 5:47). He’d play either pianissimo or fortissimo, with strange accents. Anthony Tommasini of the New York Time finished his 2006 review of a Carnegie Hall concert thusly: "Here is an immense talent gone tragically astray. What went wrong?" It’s impossible to answer this question, but there are many of Pogorelich’s recordings that could be enjoyed today. The Hob. XVI:19 is one of them. Every one of Haydn’s musical ideas is brilliantly enunciated, every line is clear, the sound is beautiful, everything is balanced – a great performance overall. Listen to it here.