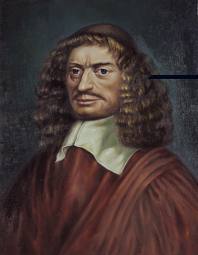

This Week in Classical Music: June 21, 2021.A Wrong Portrait.Some years ago we published an entry about an interesting early-Baroque Italian composer Giacomo Carissimi.We decided to include his portrait, as we often do when we write about a composer or a performer, so we searched the web and came up with the portrait you see to theleft.It was used on many sites, some quite established, for example, France Musique, a French national public music channel.Then some time ago we received an email from one of our listeners, who told us that the portrait is not of Carissimi at all.That was surprising, so we decided to research the matter.Sure enough, almost immediately we came across an old article by the musicologist Gloria Rose called A Portrait Called Carissimi.In this article Rose wrote about the origins of the portrait: it could be found at the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris as the frontispiece to a manuscript containing numerous works by Carissimi.Moreover, this is the only surviving portrait of the composer: while Giuseppe Ottavio Pitoni, a composer and music theorist who lived in Rome in the first half of the 18th century, made references to another portrait of Carissimi, but that one is lost.Somehow Ms. Rose felt uneasy about the portrait on the manuscript, mostly because the inscription below it was scraped off and the name of Giacomo Carissimi written in.She also learned that the painter of the portrait, the Dutchman Wallerant Vaillant, had never been to Italy, while Carissimi never left it.All these doubts pushed Ms. Rose to investigate the portrait further. To make a long story short, in the end she found out that the portrait was not of Carissimi, but of one Alexander Morus (his last name sometimes is spelled as More).Morus, whose father was Scottish, was a Protestant preacher born in 1616 in Castres, France.He died in 1670 in Paris.Morus taught at a Huguenot college in Castres, then moved to Geneva where he became a professor of the Greek language, and later lived in Amsterdam, where he was a professor of theology at Amsterdam University.It was during those years that Vaillant painted his portrait, and this portrait was well known at the time.Why a scribe preparing a manuscript of Carissimi would use a wrong portrait is not clear.Here’s what Ms. Rose writes about this matter: “This scribe must have thought that his manuscript would look more impressive if it contained a portrait of the composer. Equally, he must have known that this portrait was not a portrait of the composer. Carissimi (I605-74) and More (1616-70) would have been near the same age at the time. But it was surely an act of boldness, to say the least, to take the portrait of a French Protestant theologian.”

A brief note on Gloria Rose.She was born in 1933, received her Ph.D. from Yale and taught at the University of Pittsburgh.Her research dealt with 17th-century Italian music, particularly Carissimi’s chamber cantata.She was married to Robert Donington, a British musicologist and a specialist in early music.Ms. Rose died in 1974, at just 40 years old.

Wrong Portrait

This Week in Classical Music: June 21, 2021. A Wrong Portrait. Some years ago we published an entry about an interesting early-Baroque Italian composer Giacomo Carissimi. We decided to include his portrait, as we often do when we write about a composer or a performer, so we searched the web and came up with the portrait you see to theleft. It was used on many sites, some quite established, for example, France Musique, a French national public music channel. Then some time ago we received an email from one of our listeners, who told us that the portrait is not of Carissimi at all. That was surprising, so we decided to research the matter. Sure enough, almost immediately we came across an old article by the musicologist Gloria Rose called A Portrait Called Carissimi. In this article Rose wrote about the origins of the portrait: it could be found at the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris as the frontispiece to a manuscript containing numerous works by Carissimi. Moreover, this is the only surviving portrait of the composer: while Giuseppe Ottavio Pitoni, a composer and music theorist who lived in Rome in the first half of the 18th century, made references to another portrait of Carissimi, but that one is lost. Somehow Ms. Rose felt uneasy about the portrait on the manuscript, mostly because the inscription below it was scraped off and the name of Giacomo Carissimi written in. She also learned that the painter of the portrait, the Dutchman Wallerant Vaillant, had never been to Italy, while Carissimi never left it. All these doubts pushed Ms. Rose to investigate the portrait further. To make a long story short, in the end she found out that the portrait was not of Carissimi, but of one Alexander Morus (his last name sometimes is spelled as More). Morus, whose father was Scottish, was a Protestant preacher born in 1616 in Castres, France. He died in 1670 in Paris. Morus taught at a Huguenot college in Castres, then moved to Geneva where he became a professor of the Greek language, and later lived in Amsterdam, where he was a professor of theology at Amsterdam University. It was during those years that Vaillant painted his portrait, and this portrait was well known at the time. Why a scribe preparing a manuscript of Carissimi would use a wrong portrait is not clear. Here’s what Ms. Rose writes about this matter: “This scribe must have thought that his manuscript would look more impressive if it contained a portrait of the composer. Equally, he must have known that this portrait was not a portrait of the composer. Carissimi (I605-74) and More (1616-70) would have been near the same age at the time. But it was surely an act of boldness, to say the least, to take the portrait of a French Protestant theologian.”

decided to include his portrait, as we often do when we write about a composer or a performer, so we searched the web and came up with the portrait you see to theleft. It was used on many sites, some quite established, for example, France Musique, a French national public music channel. Then some time ago we received an email from one of our listeners, who told us that the portrait is not of Carissimi at all. That was surprising, so we decided to research the matter. Sure enough, almost immediately we came across an old article by the musicologist Gloria Rose called A Portrait Called Carissimi. In this article Rose wrote about the origins of the portrait: it could be found at the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris as the frontispiece to a manuscript containing numerous works by Carissimi. Moreover, this is the only surviving portrait of the composer: while Giuseppe Ottavio Pitoni, a composer and music theorist who lived in Rome in the first half of the 18th century, made references to another portrait of Carissimi, but that one is lost. Somehow Ms. Rose felt uneasy about the portrait on the manuscript, mostly because the inscription below it was scraped off and the name of Giacomo Carissimi written in. She also learned that the painter of the portrait, the Dutchman Wallerant Vaillant, had never been to Italy, while Carissimi never left it. All these doubts pushed Ms. Rose to investigate the portrait further. To make a long story short, in the end she found out that the portrait was not of Carissimi, but of one Alexander Morus (his last name sometimes is spelled as More). Morus, whose father was Scottish, was a Protestant preacher born in 1616 in Castres, France. He died in 1670 in Paris. Morus taught at a Huguenot college in Castres, then moved to Geneva where he became a professor of the Greek language, and later lived in Amsterdam, where he was a professor of theology at Amsterdam University. It was during those years that Vaillant painted his portrait, and this portrait was well known at the time. Why a scribe preparing a manuscript of Carissimi would use a wrong portrait is not clear. Here’s what Ms. Rose writes about this matter: “This scribe must have thought that his manuscript would look more impressive if it contained a portrait of the composer. Equally, he must have known that this portrait was not a portrait of the composer. Carissimi (I605-74) and More (1616-70) would have been near the same age at the time. But it was surely an act of boldness, to say the least, to take the portrait of a French Protestant theologian.”

A brief note on Gloria Rose. She was born in 1933, received her Ph.D. from Yale and taught at the University of Pittsburgh. Her research dealt with 17th-century Italian music, particularly Carissimi’s chamber cantata. She was married to Robert Donington, a British musicologist and a specialist in early music. Ms. Rose died in 1974, at just 40 years old.