This Week in Classical Music: September 12, 2022.Schoenberg, Part I, the Early Years.Arnold Schoenberg, one of the most consequential composers of the 20th century, was born on September 13th in 1874.It has been some time since we last attempted to write about him, and clearly, it’s impossible to describe the life and music of such a complex figure in one entry.We’ll try to sketch part of it here and will continue at a later date.

Schoenberg was born in Leopoldstadt, a heavily Jewish district of Vienna.His family was lower middle class, the father a shoe-shopkeeper, the mother a piano teacher.Musically, Schoenberg was mostly self-taught: he learned to play the cello himself, and the only lessons he took were from Alexander von Zemlinsky, a friend in whose amateur orchestra Schoenberg played, while working full time as a bank clerk.Even though Zemlinksy was by then an established composer, writing in a late-Romantic style, it’s not clear how much help he provided to his student: Zemlinksy said that they mostly exchanged scores and commented on each other’s work.In 1897 Schoenberg’s quartet, edited according to Zemlinksy’s suggestions, was performed in Vienna and was well received.The following piece, the string sextet Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night), submitted by Schoenberg in 1899, was rejected by the Vienna Music Society and premiered only three years later.The piece was tonal but heavily chromatic and wondering away from the home key (you can listen to it here, played by the young students of the Steans Institute).The performance created a scandal, which would become a constant in practically all premieres of Schoenberg’s work from that point on.In the meantime, he was earning a living conducting choral societies and orchestrating operettas, a popular entertainment in Germany and Austria-Hungary.He was also composing and in 1901 completed a large cantata, Gurre-Lieder.That same year he married Zemlinsky’s sister Mathilde; later that year the couple moved to Berlin.For a while Schoenberg worked as the music director of Überbrettl, a fashionable cabaret frequented by the literati and musicians. That job ended a year later but in a lucky break, Schoenberg met Richard Strauss and showed him two pieces, Gurre-Lieder and the new symphonic poem Pelleas und Melisande.Strauss was impressed and helped Schoenberg to obtain a stipend at the Stern Conservatory, a prestigious private school which is now part of Berlin University of the Arts.He returned to Vienna in 1903.

In Vienna Schoenberg joined Zemlinky in teaching several private music classes.Some of the attendees were students of one Guido Adler.Adler is now half-forgotten, but his role in the Austro-German music world is interesting.Adler, Jewish, like Schoenberg and Zemlinksy (and Mahler), was Mahler’s friend and Bruckner’s pupil at the Vienna Conservatory.Adler practically created musicology as the scientific field we know today.He taught at the University of Vienna and the German University of Prague. One of his students wasAnton Webern, who joined Schoenberg’s class.Another young composer,Alban Bergsoon also joined the group.The relationship between Schoenberg and his two students, Webern and Berg, is legendary, and became central in Schoenberg’s life, as of course it was for the younger composers.

Private teaching and composing weren’t bringing much money, so, to get some funding, Schoenberg, together with Zemlinsky, managed to create a music society.Moreover, they succeeded in appointing Mahler their honorary president (Mahler had heard Verklärte Nacht a year earlier and was very impressed).The society survived for one year only but managed to present, among other piece of new music, Schoenberg’s Pelleas und Melisande.Here it is, in the performance by the Staatskapelle Berlin, Daniel Barenboim conducting.

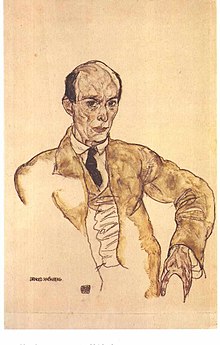

Arnold Schoenberg, part I, 2022

This Week in Classical Music: September 12, 2022. Schoenberg, Part I, the Early Years. Arnold Schoenberg, one of the most consequential composers of the 20th century, was born on September 13th in 1874. It has been some time since we last attempted to write about him, and clearly, it’s impossible to describe the life and music of such a complex figure in one entry. We’ll try to sketch part of it here and will continue at a later date.

September 13th in 1874. It has been some time since we last attempted to write about him, and clearly, it’s impossible to describe the life and music of such a complex figure in one entry. We’ll try to sketch part of it here and will continue at a later date.

Schoenberg was born in Leopoldstadt, a heavily Jewish district of Vienna. His family was lower middle class, the father a shoe-shopkeeper, the mother a piano teacher. Musically, Schoenberg was mostly self-taught: he learned to play the cello himself, and the only lessons he took were from Alexander von Zemlinsky, a friend in whose amateur orchestra Schoenberg played, while working full time as a bank clerk. Even though Zemlinksy was by then an established composer, writing in a late-Romantic style, it’s not clear how much help he provided to his student: Zemlinksy said that they mostly exchanged scores and commented on each other’s work. In 1897 Schoenberg’s quartet, edited according to Zemlinksy’s suggestions, was performed in Vienna and was well received. The following piece, the string sextet Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night), submitted by Schoenberg in 1899, was rejected by the Vienna Music Society and premiered only three years later. The piece was tonal but heavily chromatic and wondering away from the home key (you can listen to it here, played by the young students of the Steans Institute). The performance created a scandal, which would become a constant in practically all premieres of Schoenberg’s work from that point on. In the meantime, he was earning a living conducting choral societies and orchestrating operettas, a popular entertainment in Germany and Austria-Hungary. He was also composing and in 1901 completed a large cantata, Gurre-Lieder. That same year he married Zemlinsky’s sister Mathilde; later that year the couple moved to Berlin. For a while Schoenberg worked as the music director of Überbrettl, a fashionable cabaret frequented by the literati and musicians. That job ended a year later but in a lucky break, Schoenberg met Richard Strauss and showed him two pieces, Gurre-Lieder and the new symphonic poem Pelleas und Melisande. Strauss was impressed and helped Schoenberg to obtain a stipend at the Stern Conservatory, a prestigious private school which is now part of Berlin University of the Arts. He returned to Vienna in 1903.

In Vienna Schoenberg joined Zemlinky in teaching several private music classes. Some of the attendees were students of one Guido Adler. Adler is now half-forgotten, but his role in the Austro-German music world is interesting. Adler, Jewish, like Schoenberg and Zemlinksy (and Mahler), was Mahler’s friend and Bruckner’s pupil at the Vienna Conservatory. Adler practically created musicology as the scientific field we know today. He taught at the University of Vienna and the German University of Prague. One of his students was Anton Webern, who joined Schoenberg’s class. Another young composer, Alban Berg soon also joined the group. The relationship between Schoenberg and his two students, Webern and Berg, is legendary, and became central in Schoenberg’s life, as of course it was for the younger composers.

Private teaching and composing weren’t bringing much money, so, to get some funding, Schoenberg, together with Zemlinsky, managed to create a music society. Moreover, they succeeded in appointing Mahler their honorary president (Mahler had heard Verklärte Nacht a year earlier and was very impressed). The society survived for one year only but managed to present, among other piece of new music, Schoenberg’s Pelleas und Melisande. Here it is, in the performance by the Staatskapelle Berlin, Daniel Barenboim conducting.