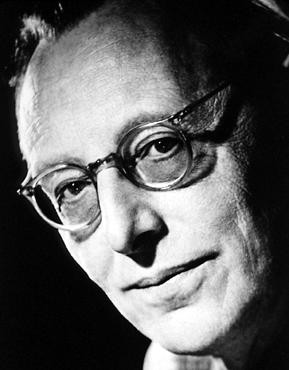

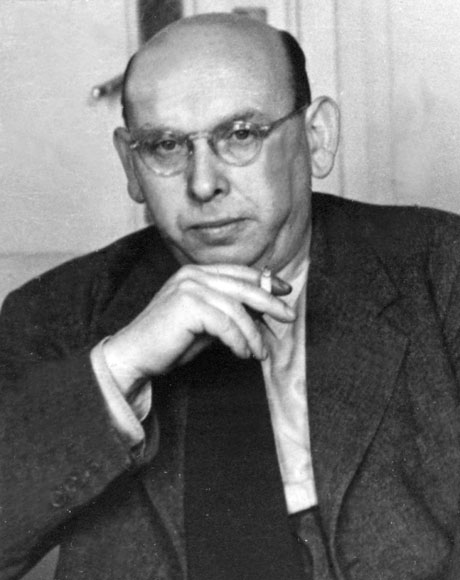

This Week in Classical Music: July 10, 2023.Hanns Eislerand Carl Orff. Carl Orff was born on this day in 1895.Hanns Eisler’s anniversary was three days ago, he was born in 1898.Last week we promised to write about these two composers: close contemporaries, they lived through the dreadful 12 years of Nazi rule.It’s interesting how differently their lives turned out.In a way, some of it was inevitable, given the antisemitism of the Nazi ideology: Eisler’s father was Jewish while Orff was a Bavarian whose father was an officer in the German Imperial Army.Still, many personal choices lead to their very different paths.(While this is the first time we’re writing about Hanns Eisler, we posted a detailed entry on Orff four years ago, you can read it here).Both Orff and Eisler served during the Great War, both were wounded (Orff severely, barely surviving).After the war, Orff moved to Munich, while Eisler returned to Vienna where he became Arnold Schoenberg’s student; five years later Eisler moved back to Germany and settled in Berlin.The cities, Berlin and Munich, were musical centers of Germany, though Berlin at the time was an epicenter of experimentation, while Munich’s musical establishment was more conservative.During the early years of the Weimar Republic, Orff and Eisler were adventuresome composers, though Eisler more so: he was the first of Schoenberg’s students to write music in the 12-tone system, while Orff was more inspired by Stravinsky.Both were profoundly influenced by the playwright and Marxist firebrand Bertolt Brecht, again Eisler more so than Orff – he maintained a relationship with Brech for the rest of his life, in Germany, then in the US, and later in the GDR.

In the mid-1920s their paths started to diverge: Orff got interested in musical education and in the music of early Italian opera composers, especially Monteverdi.Eisler in the meantime was turning more and more political.Here’s one of the songs from Eisler’s cycle Zeitungsausschnitt or Newspaper Clippings.It’s called Kriegslied eines Kindes (War Song of a Child).The soprano Anna Prohaska is accompanied by Eric Schneider.And here’s another wonderful song from the same cycle, Mariechen.This short “clipping” is performed by Irmgard Arnold (soprano) and Andre Asriel (piano).Also during those last years of the Weimer, Eisler wrote music to several of Brecht’s plays.Sometime around 1931, Eisler composed a then-famous (or in our opinion, infamous) song Solidaritätslied (Song of Solidarity) for the German Communist Party with the lyrics by Brecht.For all we know, with very little change in the lyrics it could’ve been a Nazi march, but as is, it was tremendously popular with the German Left before the Nazis took over.Here it is; Hannes Wader, a popular West German singer and a member of the German Communist Party, performs it to an appreciative audience sometime around 1977.

Things changed dramatically with the Nazi’s rise to power in 1933. Orff felt quite comfortable with the new regime, even though he never joined the Nazi party.In 1937 he composed his most famous work, Carmina Burana, a cantata based on the German Latin-language poems from the 11th-12th centuries.It became very popular in Germany and, after some hesitation, was embraced by the Nazi regime.It’s not clear why would the Nazi ideologues accepted this piece and its rather salty lyrics, but they did.But so did many liberal opponents of the regime, clearly there was no “fascist message” in the music itself.Unfortunately, Orff compromised himself on other occasions. For example, when the Nazis decided that Mendelssohn’s music to Midsummer Night’s Dream was no longer acceptable, because of its Jewish provenance, he answered their call and agreed to write a replacement.Here’s a scene from Ein Sommernachtstraum called Mondaufgang (Moonrise).The Academy of the Munich Radio Orchestra is conducted by Christian von Gehren.Our feeling is that were it performed more widely these days it would become very popular (as is, its story makes it a rather politically incorrect piece).

Eisler’s life after 1933 couldn’t have been more different.We’ll continue with it next week.

Eisler and Orff, 2023

This Week in Classical Music: July 10, 2023. Hanns Eisler and Carl Orff. Carl Orff was born on this day in 1895. Hanns Eisler’s anniversary was three days ago, he was born in 1898. Last week we promised to write about these two composers: close contemporaries, they lived through the dreadful 12 years of Nazi rule. It’s interesting how differently their lives turned out. In a way, some of it was inevitable, given the antisemitism of the Nazi ideology: Eisler’s father was Jewish while Orff was a Bavarian whose father was an officer in the German Imperial Army. Still, many personal choices lead to their very different paths. (While this is the first time we’re writing about Hanns Eisler, we posted a detailed entry on Orff four years ago, you can read it here). Both Orff and Eisler served during the Great War, both were wounded (Orff severely, barely surviving). After the war, Orff moved to Munich, while Eisler returned to Vienna where he became Arnold Schoenberg’s student; five years later Eisler moved back to Germany and settled in Berlin. The cities, Berlin and Munich, were musical centers of Germany, though Berlin at the time was an epicenter of experimentation, while Munich’s musical establishment was more conservative.

Last week we promised to write about these two composers: close contemporaries, they lived through the dreadful 12 years of Nazi rule. It’s interesting how differently their lives turned out. In a way, some of it was inevitable, given the antisemitism of the Nazi ideology: Eisler’s father was Jewish while Orff was a Bavarian whose father was an officer in the German Imperial Army. Still, many personal choices lead to their very different paths. (While this is the first time we’re writing about Hanns Eisler, we posted a detailed entry on Orff four years ago, you can read it here). Both Orff and Eisler served during the Great War, both were wounded (Orff severely, barely surviving). After the war, Orff moved to Munich, while Eisler returned to Vienna where he became Arnold Schoenberg’s student; five years later Eisler moved back to Germany and settled in Berlin. The cities, Berlin and Munich, were musical centers of Germany, though Berlin at the time was an epicenter of experimentation, while Munich’s musical establishment was more conservative.  During the early years of the Weimar Republic, Orff and Eisler were adventuresome composers, though Eisler more so: he was the first of Schoenberg’s students to write music in the 12-tone system, while Orff was more inspired by Stravinsky. Both were profoundly influenced by the playwright and Marxist firebrand Bertolt Brecht, again Eisler more so than Orff – he maintained a relationship with Brech for the rest of his life, in Germany, then in the US, and later in the GDR.

During the early years of the Weimar Republic, Orff and Eisler were adventuresome composers, though Eisler more so: he was the first of Schoenberg’s students to write music in the 12-tone system, while Orff was more inspired by Stravinsky. Both were profoundly influenced by the playwright and Marxist firebrand Bertolt Brecht, again Eisler more so than Orff – he maintained a relationship with Brech for the rest of his life, in Germany, then in the US, and later in the GDR.

In the mid-1920s their paths started to diverge: Orff got interested in musical education and in the music of early Italian opera composers, especially Monteverdi. Eisler in the meantime was turning more and more political. Here’s one of the songs from Eisler’s cycle Zeitungsausschnitt or Newspaper Clippings. It’s called Kriegslied eines Kindes (War Song of a Child). The soprano Anna Prohaska is accompanied by Eric Schneider. And here’s another wonderful song from the same cycle, Mariechen. This short “clipping” is performed by Irmgard Arnold (soprano) and Andre Asriel (piano). Also during those last years of the Weimer, Eisler wrote music to several of Brecht’s plays. Sometime around 1931, Eisler composed a then-famous (or in our opinion, infamous) song Solidaritätslied (Song of Solidarity) for the German Communist Party with the lyrics by Brecht. For all we know, with very little change in the lyrics it could’ve been a Nazi march, but as is, it was tremendously popular with the German Left before the Nazis took over. Here it is; Hannes Wader, a popular West German singer and a member of the German Communist Party, performs it to an appreciative audience sometime around 1977.

Things changed dramatically with the Nazi’s rise to power in 1933. Orff felt quite comfortable with the new regime, even though he never joined the Nazi party. In 1937 he composed his most famous work, Carmina Burana, a cantata based on the German Latin-language poems from the 11th-12th centuries. It became very popular in Germany and, after some hesitation, was embraced by the Nazi regime. It’s not clear why would the Nazi ideologues accepted this piece and its rather salty lyrics, but they did. But so did many liberal opponents of the regime, clearly there was no “fascist message” in the music itself. Unfortunately, Orff compromised himself on other occasions. For example, when the Nazis decided that Mendelssohn’s music to Midsummer Night’s Dream was no longer acceptable, because of its Jewish provenance, he answered their call and agreed to write a replacement. Here’s a scene from Ein Sommernachtstraum called Mondaufgang (Moonrise). The Academy of the Munich Radio Orchestra is conducted by Christian von Gehren. Our feeling is that were it performed more widely these days it would become very popular (as is, its story makes it a rather politically incorrect piece).

Eisler’s life after 1933 couldn’t have been more different. We’ll continue with it next week.