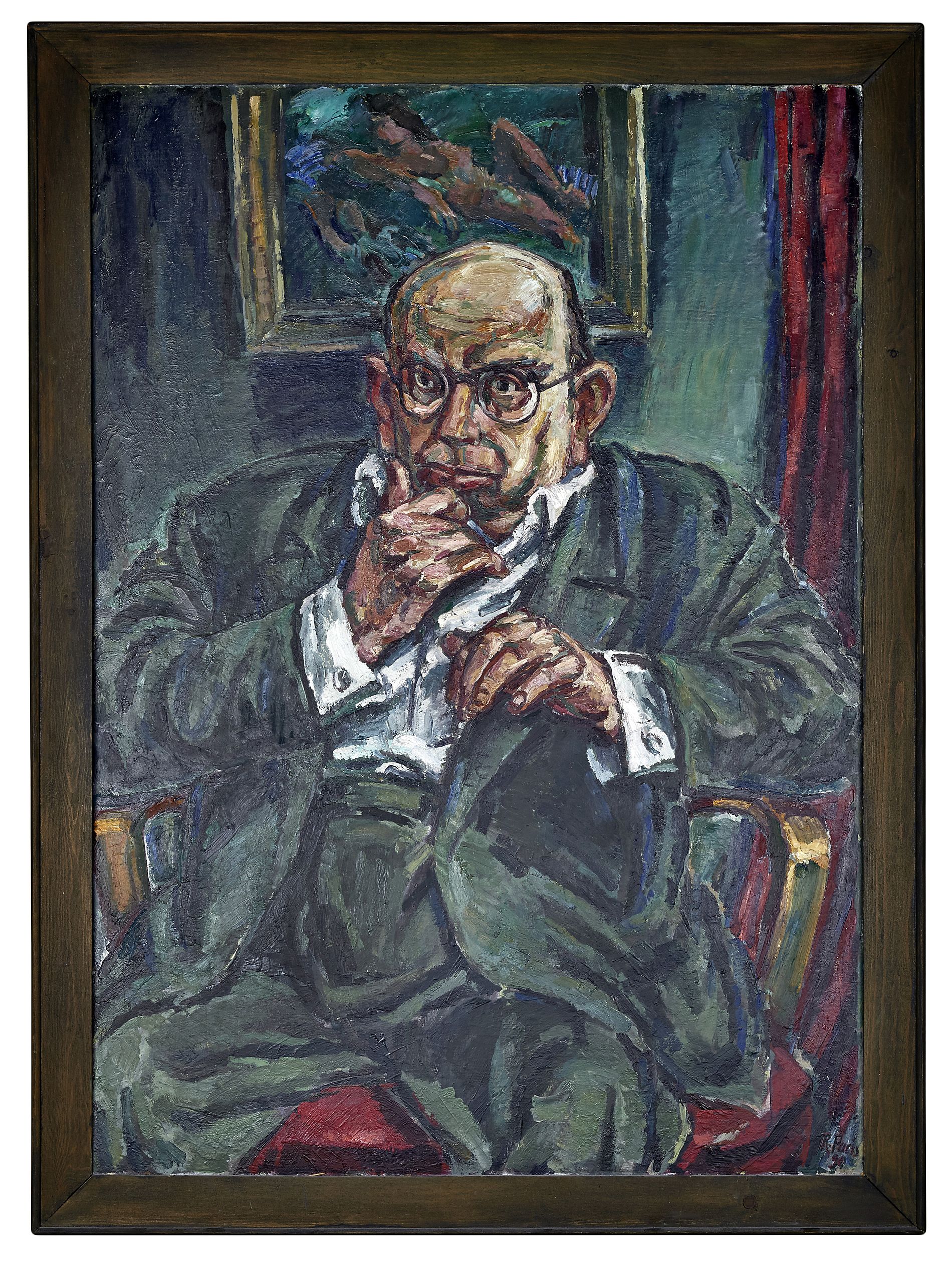

This Week in Classical Music: July 17, 2023.Hanns Eislerand Carl Orff, Part II. We’ll continue with the story of the lives of two German composers, both talented, born at about the same time, but whose lives took very different turns during the Nazi era.Carl Orff became one of the Nazi establishment’s favorite composers; his Carmina Burana (1937) and Catulli Carmina (finished in 1943) were performed across Germany.Hanns Eisler, on the other hand, had it much harder.In 1933 his music was banned (as were the works of his friend Bertolt Brecht).Both emigrated the same year; Brecht settled in Denmark, while Eisler became peripatetic: he went to the US on a speech tour, then Vienna, France, Moscow, Mexico and Denmark.In some of these places he worked on film scores; while in Denmark he collaborated with Brecht, writing music for one of his plays.He visited Spain during the Civil War where he went to the front lines.During one of his subsequent visits to the US he taught composition at the New School for Social Research in New York.In 1940 he received a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation and moved to New York, and two years later to southern California where there was already a large German émigré community.Brecht moved there too (in 1941), and again Eisler joined him in writing music to Galileo and other plays.He also collaborated with the philosopher and musicologist Theodor Adorno, one of the many German emigres living in “Weimar on the Pacific,” on a book about music in films.And Eisler wasn’t just writing, he was also composing music for films, and many of them, thus making a decent living.

It all came to an end when Eisler, Brecht, and several other Hollywood personalities were brought before the Congress’ Committee on Un-American Activities.He was accused, among other things, of being a brother of a “communist spy” Gerhart Eisler, and was labeled "the Karl Marx of music" (his brother Gerhart very likely was a spy as for many years he worked for the Comintern as a liaison – not that this somehow excuses the actions of the HUAC).Eisler’s case became an international cause célèbre, and many artists came to his defense, Charlie Chaplin, Thomas Mann, Albert Einstein, Pablo Picasso, and Henri Matisse among them.Eisler was expelled from the US in 1948.He returned to Vienna but soon after moved to East Berlin, then the capital of the German Democratic Republic.There he wrote a song which became the national anthem of the GDR.He became a professor at the Berlin Hochschule für Musik and a member of the Academy of Arts.And while he was feted and living in a “workers’ paradise” consistent with his doctrinaire political beliefs, the reality of GDR wasn’t easy even for him.In 1953 he decided to write an opera about Faustus, but the libretto was criticized as “formalistic” – that was Eisler’s last attempt to write an opera.One big positive was that his good friend Brecht was also living in Berlin, and they continued to collaborate on many of his plays (Eisler’s brother Gerhart was also there: he escaped the US in 1948, moved to East Germany, and became a senior executive in the governing Socialist Unity Party).But in 1956 Brecht died and that scarred Eisler for the rest of his life.He continued to compose, mostly songs but also what he called Angewandte Musik (applied music)” music for film and plays.Eisler died in East Berlin in 1962.

We’ll finish our story and listen to some music by Orff and Eisner next week.

Orff and Eisler, part II, 2023

This Week in Classical Music: July 17, 2023. Hanns Eisler and Carl Orff, Part II. We’ll continue with the story of the lives of two German composers, both talented, born at about the same time, but whose lives took very different turns during the Nazi era. Carl Orff became one of the Nazi establishment’s favorite composers; his Carmina Burana (1937) and Catulli Carmina (finished in 1943) were performed across Germany. Hanns Eisler, on the other hand, had it much harder. In 1933 his music was banned (as were the works of his friend Bertolt Brecht). Both emigrated the same year; Brecht settled in Denmark, while Eisler became peripatetic: he went to the US on a speech tour, then Vienna, France, Moscow, Mexico and Denmark. In some of these places he worked on film scores; while in Denmark he collaborated with Brecht, writing music for one of his plays. He visited Spain during the Civil War where he went to the front lines. During one of his subsequent visits to the US he taught composition at the New School for Social Research in New York. In 1940 he received a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation and moved to New York, and two years later to southern California where there was already a large German émigré community. Brecht moved there too (in 1941), and again Eisler joined him in writing music to Galileo and other plays. He also collaborated with the philosopher and musicologist Theodor Adorno, one of the many German emigres living in “Weimar on the Pacific,” on a book about music in films. And Eisler wasn’t just writing, he was also composing music for films, and many of them, thus making a decent living.

same time, but whose lives took very different turns during the Nazi era. Carl Orff became one of the Nazi establishment’s favorite composers; his Carmina Burana (1937) and Catulli Carmina (finished in 1943) were performed across Germany. Hanns Eisler, on the other hand, had it much harder. In 1933 his music was banned (as were the works of his friend Bertolt Brecht). Both emigrated the same year; Brecht settled in Denmark, while Eisler became peripatetic: he went to the US on a speech tour, then Vienna, France, Moscow, Mexico and Denmark. In some of these places he worked on film scores; while in Denmark he collaborated with Brecht, writing music for one of his plays. He visited Spain during the Civil War where he went to the front lines. During one of his subsequent visits to the US he taught composition at the New School for Social Research in New York. In 1940 he received a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation and moved to New York, and two years later to southern California where there was already a large German émigré community. Brecht moved there too (in 1941), and again Eisler joined him in writing music to Galileo and other plays. He also collaborated with the philosopher and musicologist Theodor Adorno, one of the many German emigres living in “Weimar on the Pacific,” on a book about music in films. And Eisler wasn’t just writing, he was also composing music for films, and many of them, thus making a decent living.

It all came to an end when Eisler, Brecht, and several other Hollywood personalities were brought before the Congress’ Committee on Un-American Activities. He was accused, among other things, of being a brother of a “communist spy” Gerhart Eisler, and was labeled "the Karl Marx of music" (his brother Gerhart very likely was a spy as for many years he worked for the Comintern as a liaison – not that this somehow excuses the actions of the HUAC). Eisler’s case became an international cause célèbre, and many artists came to his defense, Charlie Chaplin, Thomas Mann, Albert Einstein, Pablo Picasso, and Henri Matisse among them. Eisler was expelled from the US in 1948. He returned to Vienna but soon after moved to East Berlin, then the capital of the German Democratic Republic. There he wrote a song which became the national anthem of the GDR. He became a professor at the Berlin Hochschule für Musik and a member of the Academy of Arts. And while he was feted and living in a “workers’ paradise” consistent with his doctrinaire political beliefs, the reality of GDR wasn’t easy even for him. In 1953 he decided to write an opera about Faustus, but the libretto was criticized as “formalistic” – that was Eisler’s last attempt to write an opera. One big positive was that his good friend Brecht was also living in Berlin, and they continued to collaborate on many of his plays (Eisler’s brother Gerhart was also there: he escaped the US in 1948, moved to East Germany, and became a senior executive in the governing Socialist Unity Party). But in 1956 Brecht died and that scarred Eisler for the rest of his life. He continued to compose, mostly songs but also what he called Angewandte Musik (applied music)” music for film and plays. Eisler died in East Berlin in 1962.

We’ll finish our story and listen to some music by Orff and Eisner next week.