November 24, 2014.Alfred Schnittke.We have to admit to having a problem with the term “Soviet,” as in “Soviet composer.”There is just so much negativity associated with the term, with all the totalitarian connotations and the evil that was perpetrated under its name during a large part of the 20th century.But what would you call a composer born on November 24th of 1934 in a city on river Volga, who then moved to Moscow, studied and later taught at the Moscow Conservatory, and was for a while a member of the Soviet Composer’s Union?On the other hand, what would you call a composer whose music was so non-conformist and “anti-Soviet” that it was banned by the same Composer’s Union?The life of Alfred Schnittke, one of the most interesting composers of the last half of the 20th century, was very unusual.He was born into a German-Jewish family.His Jewish father Harry was born in Frankfurt but brought to the Soviet Union in 1927 by his parents who, like so many Western intellectuals at that time, went to Russia to build a new, just society.Most of them perished in the Gulag, but not the Schnittkes.Harry became a well-known German translator and a journalist.During the Great Patriotic War, as WWII was called in the Soviet Union, Harry worked as a wartime correspondent.Once the war was over, he was stationed in Soviet-occupied Vienna to work in a newspaper established by the Soviet authorities.Harry brought his family with him, including the 12-year-old Alfred.It was in Vienna, the city of Mozart and Haydn, Beethoven and Schubert, Bruckner and Mahler, that Alfred started his musical education.Even though the family stayed in Vienna for just two years, the exposure to the Austrian-German tradition deeply influenced young Schnittke.They returned to the Soviet Union in 1948 and settled in the suburbs of Moscow.Alfred attended a music school and in 1953 entered the Moscow Conservatory, studying composition with Evgeny Golubev, a pupil of Myaskovsky, and eventually doing graduate work.In 1962 he assumed an assistant teaching position at the Conservatory but earned his living writing film scores.His relationship with the Soviet musical establishment was difficult from the beginning.Some of his work was banned and most of it rarely performed.He became officially accepted only in the late 1980s, during Gorbachev’s Perestroika.

Schnittke was a very prolific composer, writing several operas, 10 symphonies, four violin concertos, several piano concertos, and many chamber and instrumental pieces.His early music was deeply influenced by Shostakovich, but eventually Schnittke evolved into a highly original composer.In 1971 he wrote an essay titled “Polystylistic Tendencies in Modern Music.”In it Schnittke pointed to composers he called “polystylistic,” who mixed and matched various styles into a coherent composition; those, in Schnittke’s opinion, included Luciano Berio, Edison Denisov, Krzysztof Penderecki and other.But it was Schnittke himself who became a major proponent of this style.

In 1985 Schnittke suffered a terrible stroke (doctors believed they had lost him several times) but recovered and continued composing, though his style became more introverted.In 1990 Schnittke left Russia and settled in Hamburg.He had another stroke in 1995, which paralyzed him; after that he stopped composing.Schnittke died in Hamburg on August 5th, 1998.His body was returned to Moscow and buried with state honors.

We have a number of Schnittke’s works in our library.Here’s his "polystylistic" and very representative piece from 1977 called Concerto Grosso No. 1.It’s performed by the dedicatees of the piece, the violinists Gidon Kremer and his then wife Tatiana Grindenko and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, Heinrich Schiff conducting.

Jean-Baptiste Lully, the father of French Baroque, was born on 28th of November 1632.We’ll commemorate his birthday at a later date.

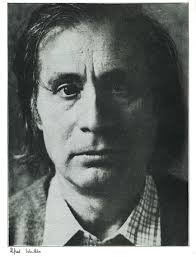

Alfred Schnittke 2014

November 24, 2014. Alfred Schnittke. We have to admit to having a problem with the term “Soviet,” as in “Soviet composer.” There is just so much negativity associated with the term, with all the totalitarian connotations and the evil that was perpetrated under its name during a large part of the 20th century. But what would you call a composer born on November 24th of 1934 in a city on river Volga, who then moved to Moscow, studied and later taught at the Moscow Conservatory, and was for a while a member of the Soviet Composer’s Union? On the other hand, what would you call a composer whose music was so non-conformist and “anti-Soviet” that it was banned by the same Composer’s Union? The life of Alfred Schnittke, one of the most interesting composers of the last half of the 20th century, was very unusual. He was born into a German-Jewish family. His Jewish father Harry was born in Frankfurt but brought to the Soviet Union in 1927 by his parents who, like so many Western intellectuals at that time, went to Russia to build a new, just society. Most of them perished in the Gulag, but not the Schnittkes. Harry became a well-known German translator and a journalist. During the Great Patriotic War, as WWII was called in the Soviet Union, Harry worked as a wartime correspondent. Once the war was over, he was stationed in Soviet-occupied Vienna to work in a newspaper established by the Soviet authorities. Harry brought his family with him, including the 12-year-old Alfred. It was in Vienna, the city of Mozart and Haydn, Beethoven and Schubert, Bruckner and Mahler, that Alfred started his musical education. Even though the family stayed in Vienna for just two years, the exposure to the Austrian-German tradition deeply influenced young Schnittke. They returned to the Soviet Union in 1948 and settled in the suburbs of Moscow. Alfred attended a music school and in 1953 entered the Moscow Conservatory, studying composition with Evgeny Golubev, a pupil of Myaskovsky, and eventually doing graduate work. In 1962 he assumed an assistant teaching position at the Conservatory but earned his living writing film scores. His relationship with the Soviet musical establishment was difficult from the beginning. Some of his work was banned and most of it rarely performed. He became officially accepted only in the late 1980s, during Gorbachev’s Perestroika.

the 20th century. But what would you call a composer born on November 24th of 1934 in a city on river Volga, who then moved to Moscow, studied and later taught at the Moscow Conservatory, and was for a while a member of the Soviet Composer’s Union? On the other hand, what would you call a composer whose music was so non-conformist and “anti-Soviet” that it was banned by the same Composer’s Union? The life of Alfred Schnittke, one of the most interesting composers of the last half of the 20th century, was very unusual. He was born into a German-Jewish family. His Jewish father Harry was born in Frankfurt but brought to the Soviet Union in 1927 by his parents who, like so many Western intellectuals at that time, went to Russia to build a new, just society. Most of them perished in the Gulag, but not the Schnittkes. Harry became a well-known German translator and a journalist. During the Great Patriotic War, as WWII was called in the Soviet Union, Harry worked as a wartime correspondent. Once the war was over, he was stationed in Soviet-occupied Vienna to work in a newspaper established by the Soviet authorities. Harry brought his family with him, including the 12-year-old Alfred. It was in Vienna, the city of Mozart and Haydn, Beethoven and Schubert, Bruckner and Mahler, that Alfred started his musical education. Even though the family stayed in Vienna for just two years, the exposure to the Austrian-German tradition deeply influenced young Schnittke. They returned to the Soviet Union in 1948 and settled in the suburbs of Moscow. Alfred attended a music school and in 1953 entered the Moscow Conservatory, studying composition with Evgeny Golubev, a pupil of Myaskovsky, and eventually doing graduate work. In 1962 he assumed an assistant teaching position at the Conservatory but earned his living writing film scores. His relationship with the Soviet musical establishment was difficult from the beginning. Some of his work was banned and most of it rarely performed. He became officially accepted only in the late 1980s, during Gorbachev’s Perestroika.

Schnittke was a very prolific composer, writing several operas, 10 symphonies, four violin concertos, several piano concertos, and many chamber and instrumental pieces. His early music was deeply influenced by Shostakovich, but eventually Schnittke evolved into a highly original composer. In 1971 he wrote an essay titled “Polystylistic Tendencies in Modern Music.” In it Schnittke pointed to composers he called “polystylistic,” who mixed and matched various styles into a coherent composition; those, in Schnittke’s opinion, included Luciano Berio, Edison Denisov, Krzysztof Penderecki and other. But it was Schnittke himself who became a major proponent of this style.

In 1985 Schnittke suffered a terrible stroke (doctors believed they had lost him several times) but recovered and continued composing, though his style became more introverted. In 1990 Schnittke left Russia and settled in Hamburg. He had another stroke in 1995, which paralyzed him; after that he stopped composing. Schnittke died in Hamburg on August 5th, 1998. His body was returned to Moscow and buried with state honors.

We have a number of Schnittke’s works in our library. Here’s his "polystylistic" and very representative piece from 1977 called Concerto Grosso No. 1. It’s performed by the dedicatees of the piece, the violinists Gidon Kremer and his then wife Tatiana Grindenko and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, Heinrich Schiff conducting.

Jean-Baptiste Lully, the father of French Baroque, was born on 28th of November 1632. We’ll commemorate his birthday at a later date.