Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: April 15, 2024. Prokofiev, Menuhin and Pamphili. Classical Connect is still in turmoil, so we’ll be brief. Sergey Prokofiev, one of the most important.jpg) composers of the first half of the 20th century, was born this week. The English-language wiki gives his birth date as April 27th of 1891, the Russian one – as April 23rd, and so does Grove Music. It’s even more confusing because at the end of the 19th century, Russia was still using the “old style” Julian calendar, according to which Prokofiev was born on April 11th (or April 15th). Even the English spelling of his first name differs in different sources: with an “i” at the end in Wiki, but a “y” in Grove and Britannica. None of which matters much; what is important is his undeniable talent as a composer and pianist. Prokofiev left Russia after the Revolution of 1917 but then returned, unexplainably in retrospect, to the Soviet Union in 1936. He wasn’t the only one: dozens of Russian emigres, writers, artists, composers, even the members of the White Guard, returned to their land of birth, driven by nostalgia and Soviet propaganda, many of them to be arrested and killed. Prokofiev was spared, even if for some years his position was tenuous. We’ve written about Prokofiev many times, you can read more, for example, here and here.

composers of the first half of the 20th century, was born this week. The English-language wiki gives his birth date as April 27th of 1891, the Russian one – as April 23rd, and so does Grove Music. It’s even more confusing because at the end of the 19th century, Russia was still using the “old style” Julian calendar, according to which Prokofiev was born on April 11th (or April 15th). Even the English spelling of his first name differs in different sources: with an “i” at the end in Wiki, but a “y” in Grove and Britannica. None of which matters much; what is important is his undeniable talent as a composer and pianist. Prokofiev left Russia after the Revolution of 1917 but then returned, unexplainably in retrospect, to the Soviet Union in 1936. He wasn’t the only one: dozens of Russian emigres, writers, artists, composers, even the members of the White Guard, returned to their land of birth, driven by nostalgia and Soviet propaganda, many of them to be arrested and killed. Prokofiev was spared, even if for some years his position was tenuous. We’ve written about Prokofiev many times, you can read more, for example, here and here.

Yehudi Menuhin, one of the greatest violinists of the 20th century, was born in New York on this day in 1916. And we want to remember Cardinal Benedetto Pamphili, born on April 25th of 1653 in Rome. He was an important patron of arts, especially favoring composers (Handel was one of them), and a fine librettist. You can read about him here.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: April 15, 2024. Marriner, Maderna. Sir Neville Marriner, a great English conductor, was born one hundred years ago today, on April 25th of 1924 in Lincoln, UK. He started as a violinist, played in different orchestras and chamber ensembles, and in 1958 founded the Academy of St Martin in the Fields, the chamber orchestra that became world famous. Among Marriner’s friends and founding members were Iona Brown, who led the orchestra for six years from 1974 to 1980, and Christopher Hogwood, who later founded the Academy of Ancient Music. Marriner and St Marin in the Fields made more recordings than any other ensemble-conductor pair. Their repertoire was very broad, from the mainstay of the baroque and classical music of the 18th century to Mahler, Janáček, Stravinsky, Prokofiev and other composers of the 20th. In the words of Grove Music, Marriner’s performances were “distinguished by clarity, buoyant vitality, crisp ensemble, and technical polish.” Altogether, Marriner made 600 recordings, more than any other conductor except for Karajan. In 1969 Marriner co-founded the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, he served as the music director of the ensemble till 1978. Marriner was active till the very end of his life; he died in London on October 2nd of 2016, at 92.

UK. He started as a violinist, played in different orchestras and chamber ensembles, and in 1958 founded the Academy of St Martin in the Fields, the chamber orchestra that became world famous. Among Marriner’s friends and founding members were Iona Brown, who led the orchestra for six years from 1974 to 1980, and Christopher Hogwood, who later founded the Academy of Ancient Music. Marriner and St Marin in the Fields made more recordings than any other ensemble-conductor pair. Their repertoire was very broad, from the mainstay of the baroque and classical music of the 18th century to Mahler, Janáček, Stravinsky, Prokofiev and other composers of the 20th. In the words of Grove Music, Marriner’s performances were “distinguished by clarity, buoyant vitality, crisp ensemble, and technical polish.” Altogether, Marriner made 600 recordings, more than any other conductor except for Karajan. In 1969 Marriner co-founded the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, he served as the music director of the ensemble till 1978. Marriner was active till the very end of his life; he died in London on October 2nd of 2016, at 92.

Bruno Maderna, one of the most interesting and influential composers of the 20th century, was born in Venice on April 21st of 1920. Here’s our entry from some years ago.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: April 8, 2024. Sol Hurok, Impresario. He was neither a musician nor a composer, but Sol Hurok did for classical music in America more than almost any other person we can think of. Hurok was born Solomon Gurkov on April 9th of 1888 in Zarist Russia and moved to New York in 1906. A natural organizer, he started with left-wing politics in Brooklyn; that didn’t last long as he switched to representing musicians: Efrem Zimbalist and Mischa Elman, the talented violinists who also emigrated from Russia, were among his first clients. He represented the Russian bass Fyodor Chaliapin for several years (he also worked with Nellie Melba and Titta Ruffo). He then turned to dance: Anna Pavlova, Isadora Duncan, and Michel Fokine became his clients, as well as the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. In 1942, he organized one of the first tours of the American Ballet Theatre.

other person we can think of. Hurok was born Solomon Gurkov on April 9th of 1888 in Zarist Russia and moved to New York in 1906. A natural organizer, he started with left-wing politics in Brooklyn; that didn’t last long as he switched to representing musicians: Efrem Zimbalist and Mischa Elman, the talented violinists who also emigrated from Russia, were among his first clients. He represented the Russian bass Fyodor Chaliapin for several years (he also worked with Nellie Melba and Titta Ruffo). He then turned to dance: Anna Pavlova, Isadora Duncan, and Michel Fokine became his clients, as well as the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. In 1942, he organized one of the first tours of the American Ballet Theatre.

Hurok represented Marian Anderson when working with black singers was not a popular undertaking; he helped to organize Anderson’s famous concert at the Lincoln Memorial, which was broadcast nationwide and made her a household name. Among Hurok’s longest associations were those with Arthur Rubinstein and Isaac Stern. The list of Hurok’s clients read as Who-is-Who in American Music: he worked with the cellist Gregor Piatigorsky, violinists Nathan Milstein and Efrem Zimbalist, and later represented the younger stars, Van Cliburn, Jacqueline du Pré, Itzhak Perlman, and Pinchas Zukerman.

For many years Hurok tried to bring Soviet artists to America. It became possible only after Stalin’s death. The pianists Emil Gilels and violinist David Oistrakh came first, in 1955, then, later, such luminaries as Sviatoslav Richter, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Leonid Kogan and Mstislav Rostropovich. Hurok also represented the singers Galina Vishnevskaya and Irina Arkhipova and conductors Kiril Kondrashin and Yevgeny Svetlanov. Some of Hurok’s greatest coups were achieved with the ballet companies: the Bolshoi tour in 1959 was a sensational success, and so was Kirov’s, which Hurok brought in 1961.

Sol Hurok died in New York on March 5th of 1974.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: April 1, 2024. Easter Sunday was yesterday. Here is the first chorus of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, "Kommt, ihr Töchter, helft mir klagen" (Come ye daughters, join my lament). Collegium Vocale Gent is conducted by Philippe Herreweghe.

Two composers (great pianists both) were born on this day: Ferruccio Busoni in 1866 and Sergei Rachmaninov in 1873.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: March 25, 2024. Maurizio Pollini, one of the greatest pianists of the last half century, died two days ago, on March 23rd in Milan at the age of 82. His technique was phenomenal, even though he lost some of it in the last years of his life (he performed almost till the very end of his life and probably should’ve stopped earlier). His Chopin was exquisite (no wonder that he won the eponymous competition in 1960), as was the rest of the standard 19th-century piano repertoire, but he also was incomparable as the interpreter of the music of the Second Viennese School, and even more so as the performer of the contemporary music, much of it written by his friends: Luigi Nono, Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Bruno Maderna, and many other. He will be sorely missed. Speaking of Pierre Boulez: his anniversary is this week as well: he was born on March 26th of 1925.

Also this week: Franz Joseph Haydn, born March 31st of 1732; Carlo Gesualdo – on March 30th of 1556; Johann Adolph Hasse, onMarch 25 of 1699; and one of our favorite composers of the 20th century, Béla Bartók, on March 25th of 1881.Permalink

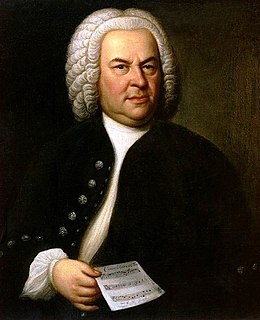

This Week in Classical Music: March 18, 2024. Classical Connect is on a hiatus. Johann Sebastian Bach was born this week, on March 21st of 1685 (old style), in Eisenach. Here is the first part of Bach’s St. John Passion, one of his supreme masterpieces.

Permalink