Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

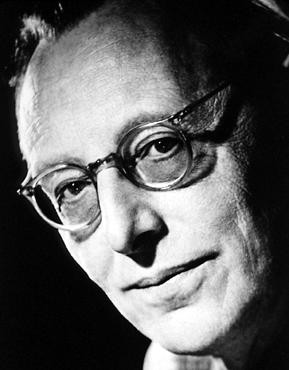

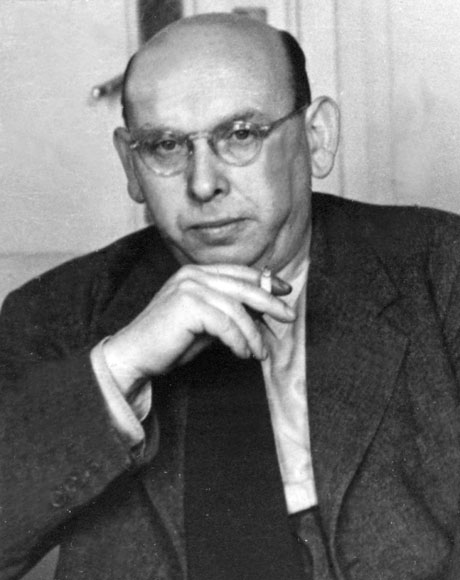

This Week in Classical Music: July 10, 2023. Hanns Eisler and Carl Orff. Carl Orff was born on this day in 1895. Hanns Eisler’s anniversary was three days ago, he was born in 1898. Last week we promised to write about these two composers: close contemporaries, they lived through the dreadful 12 years of Nazi rule. It’s interesting how differently their lives turned out. In a way, some of it was inevitable, given the antisemitism of the Nazi ideology: Eisler’s father was Jewish while Orff was a Bavarian whose father was an officer in the German Imperial Army. Still, many personal choices lead to their very different paths. (While this is the first time we’re writing about Hanns Eisler, we posted a detailed entry on Orff four years ago, you can read it here). Both Orff and Eisler served during the Great War, both were wounded (Orff severely, barely surviving). After the war, Orff moved to Munich, while Eisler returned to Vienna where he became Arnold Schoenberg’s student; five years later Eisler moved back to Germany and settled in Berlin. The cities, Berlin and Munich, were musical centers of Germany, though Berlin at the time was an epicenter of experimentation, while Munich’s musical establishment was more conservative.

Last week we promised to write about these two composers: close contemporaries, they lived through the dreadful 12 years of Nazi rule. It’s interesting how differently their lives turned out. In a way, some of it was inevitable, given the antisemitism of the Nazi ideology: Eisler’s father was Jewish while Orff was a Bavarian whose father was an officer in the German Imperial Army. Still, many personal choices lead to their very different paths. (While this is the first time we’re writing about Hanns Eisler, we posted a detailed entry on Orff four years ago, you can read it here). Both Orff and Eisler served during the Great War, both were wounded (Orff severely, barely surviving). After the war, Orff moved to Munich, while Eisler returned to Vienna where he became Arnold Schoenberg’s student; five years later Eisler moved back to Germany and settled in Berlin. The cities, Berlin and Munich, were musical centers of Germany, though Berlin at the time was an epicenter of experimentation, while Munich’s musical establishment was more conservative.  During the early years of the Weimar Republic, Orff and Eisler were adventuresome composers, though Eisler more so: he was the first of Schoenberg’s students to write music in the 12-tone system, while Orff was more inspired by Stravinsky. Both were profoundly influenced by the playwright and Marxist firebrand Bertolt Brecht, again Eisler more so than Orff – he maintained a relationship with Brech for the rest of his life, in Germany, then in the US, and later in the GDR.

During the early years of the Weimar Republic, Orff and Eisler were adventuresome composers, though Eisler more so: he was the first of Schoenberg’s students to write music in the 12-tone system, while Orff was more inspired by Stravinsky. Both were profoundly influenced by the playwright and Marxist firebrand Bertolt Brecht, again Eisler more so than Orff – he maintained a relationship with Brech for the rest of his life, in Germany, then in the US, and later in the GDR.

In the mid-1920s their paths started to diverge: Orff got interested in musical education and in the music of early Italian opera composers, especially Monteverdi. Eisler in the meantime was turning more and more political. Here’s one of the songs from Eisler’s cycle Zeitungsausschnitt or Newspaper Clippings. It’s called Kriegslied eines Kindes (War Song of a Child). The soprano Anna Prohaska is accompanied by Eric Schneider. And here’s another wonderful song from the same cycle, Mariechen. This short “clipping” is performed by Irmgard Arnold (soprano) and Andre Asriel (piano). Also during those last years of the Weimer, Eisler wrote music to several of Brecht’s plays. Sometime around 1931, Eisler composed a then-famous (or in our opinion, infamous) song Solidaritätslied (Song of Solidarity) for the German Communist Party with the lyrics by Brecht. For all we know, with very little change in the lyrics it could’ve been a Nazi march, but as is, it was tremendously popular with the German Left before the Nazis took over. Here it is; Hannes Wader, a popular West German singer and a member of the German Communist Party, performs it to an appreciative audience sometime around 1977.

Things changed dramatically with the Nazi’s rise to power in 1933. Orff felt quite comfortable with the new regime, even though he never joined the Nazi party. In 1937 he composed his most famous work, Carmina Burana, a cantata based on the German Latin-language poems from the 11th-12th centuries. It became very popular in Germany and, after some hesitation, was embraced by the Nazi regime. It’s not clear why would the Nazi ideologues accepted this piece and its rather salty lyrics, but they did. But so did many liberal opponents of the regime, clearly there was no “fascist message” in the music itself. Unfortunately, Orff compromised himself on other occasions. For example, when the Nazis decided that Mendelssohn’s music to Midsummer Night’s Dream was no longer acceptable, because of its Jewish provenance, he answered their call and agreed to write a replacement. Here’s a scene from Ein Sommernachtstraum called Mondaufgang (Moonrise). The Academy of the Munich Radio Orchestra is conducted by Christian von Gehren. Our feeling is that were it performed more widely these days it would become very popular (as is, its story makes it a rather politically incorrect piece).

Eisler’s life after 1933 couldn’t have been more different. We’ll continue with it next week.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: July 3, 2023. Mahler and more. Gustav Mahler was born on July 7th of 1860. With all the ebbs and flows in classical music tastes, he remains at the very top, acknowledged as one of the greatest European composers, beloved both by the regular listeners, judging by the number of “views” his symphonies receive on YouTube, and by music critics, based on their very subjectively compiled “best” lists. Here’s the finale (the fifth movement, Im Tempo des Scherzos) of his Symphony no. 2, Resurrection. The London Symphony Orchestra is conducted by Georg Solti. The Second Symphony was written between 1888 and 1894, while Mahler was moving from one city to another as an itinerant opera conductor. In 1888 he resigned from the Leipzig opera and went to Budapest, assuming the directorship of the Royal Hungarian Opera. He stayed there, rather unhappily, till 1891, when he was sacked, though by that time he was already negotiating a contract with the Stadttheater Hamburg, the city’s main opera house. Hired in Hamburg as the chief conductor, he later succeeded Hans von Bülow as director of the city's subscription concerts. It was also during the years in Hamburg that he established the pattern of composing during the summer months, first in Steinbach on Lake Attersee, then in Maiernigg on Lake Worthersee in Carinthia, and later in Toblach in South Tyrol. In Steinbach, the family stayed in an inn, but for his own purposes, Mahler built a tiny one-room house on the lake where he would retire to for hours and compose. It was in this hut that he completed the Second Symphony and wrote most of the Third.

Symphony and wrote most of the Third.

Several interesting composers were born this week, all deserving their own entry. Leoš Janáček, a Czech composer, was born on July 3rd of 1854. Six years older than Mahler, he was born in the same country, Austria-Hungary: Mahler in Kaliště, Bohemia, Janáček in Hukvaldy, Moravia. Bohemia and Moravia are now parts of the Czech Republic but back then were ruled by the Austrian Emperor from Vienna. But of course, this is where the similarities end. Mahler, a Jew, eventually moved to Vienna, and assumed the leadership of the Hofoper, the main opera house of the Empire (in the antisemitic Vienna to get the post he had to convert to Christianity) and composed symphonies with universal appeal (and at times, almost universal rejection). Janáček, on the other hand, became a Czech nationalist, politically supported the independence of Czechia and is considered, together with Dvořák and Smetana, one of the most important Czech composers. One of Janáček’s best-known works is the opera Jenůfa, completed in 1902. Here’s the finale, with Gabriela Beňačková in the title role. In this 1992 live recording, James Conlon conducts the Metropolitan Opera orchestra.

Ottorino Respighi, one of the most important Italian composers of the early 20th century, was born on July 9th of 1879 in Rome. Some years ago, we wrote an entry about him, you can read it here. Also, an interesting composer with a fascinating biography, Hanns Eisler was born on July 6th of 1898. We’ll write about him next week, together with his contemporary and compatriot, Carl Orff.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: June 26, 2023. Jiří Benda Jiří Antonin Benda, who is better known by his Germanized name, Georg Anton Benda, came from an illustrious family of Bohemian musicians. His father, his mother’s family and four of his siblings were musicians. Jiří was born in Staré Benátky (now Benátky nad Jizerou), a village about 25 miles from Prague on June 30th of 1722. His older brother Franz (František) became a famous violinist and found employment with the Prussian Crown Prince Frederick who later became the King of Prussia Frederick II, known as the Great. In 1743 Franz helped his family move to Prussia where Jiříjoined his brother, the Kapellmeister, in the court orchestra. In 1750 Georg, as was by then his name, became Kapellmeister at the court of Duke Friedrich III of Saxe-Gotha. There he started composing cantatas and Italian operas. After several years at the court, the Duke allowed Benda to go to Italy and even provided him with the money for the trip. In Venice Benda met the famous opera composer Johann Adolph Hasse. He also visited Bologna, Florence and Rome, where he was introduced to the modern operas of Gluck, Galuppi and others. Upon returning from Italy in 1767, Benda composed several intermezzi (short comic operas) and one of a regular length. An important event happened in 1774: a famous theatrical troupe arrived in Gotha, and Abel Seyler, the director, commissioned Brenda a “melodrama,” a staged dramatic work somewhat similar to opera but with the text being spoken rather than sung. His first melodrama, Ariadne auf Naxos, was very successful. The second melodrama, Medea, followed shortly after. Benda then composed several operas, Romeo und Julie among them. He left Gotha in 1778 to live in Hamburg and Vienna, but after failing to receive important court appointments, he returned to Gotha a year later. He retired soon after and lived on a small pension in the village of Köstritz nearby but traveled once in a while, even going to Paris to stage Ariadne at the theater Comédie-Italienne. Benda died in Köstritz on November 6th of 1795.

Bohemian musicians. His father, his mother’s family and four of his siblings were musicians. Jiří was born in Staré Benátky (now Benátky nad Jizerou), a village about 25 miles from Prague on June 30th of 1722. His older brother Franz (František) became a famous violinist and found employment with the Prussian Crown Prince Frederick who later became the King of Prussia Frederick II, known as the Great. In 1743 Franz helped his family move to Prussia where Jiříjoined his brother, the Kapellmeister, in the court orchestra. In 1750 Georg, as was by then his name, became Kapellmeister at the court of Duke Friedrich III of Saxe-Gotha. There he started composing cantatas and Italian operas. After several years at the court, the Duke allowed Benda to go to Italy and even provided him with the money for the trip. In Venice Benda met the famous opera composer Johann Adolph Hasse. He also visited Bologna, Florence and Rome, where he was introduced to the modern operas of Gluck, Galuppi and others. Upon returning from Italy in 1767, Benda composed several intermezzi (short comic operas) and one of a regular length. An important event happened in 1774: a famous theatrical troupe arrived in Gotha, and Abel Seyler, the director, commissioned Brenda a “melodrama,” a staged dramatic work somewhat similar to opera but with the text being spoken rather than sung. His first melodrama, Ariadne auf Naxos, was very successful. The second melodrama, Medea, followed shortly after. Benda then composed several operas, Romeo und Julie among them. He left Gotha in 1778 to live in Hamburg and Vienna, but after failing to receive important court appointments, he returned to Gotha a year later. He retired soon after and lived on a small pension in the village of Köstritz nearby but traveled once in a while, even going to Paris to stage Ariadne at the theater Comédie-Italienne. Benda died in Köstritz on November 6th of 1795.

As far as we can tell, Ariadne auf Naxos and Medea are the best pieces of music Benda has written. Mozart enjoyed Benda’s melodramas and in a letter to his father called them “very excellent,” adding “I like those two works of his so much that I carry them about with me.” The problem with them as a genre is that it doesn’t really work. Melodramas consist of short bursts of music, usually no longer than a minute, often of very high quality, interspersed with spoken text. The text breaks down the music’s development ark, and the text begs for a melody. No wonder it didn’t take long foropera to completely replaced the melodrama. Still, we think it’s very much worth a try. Here’s Ariadne auf Naxos. Some of the music is quite Mozartean – no wonder Wolfgang liked it. The Prague Chamber Orchestra is conducted by Christian Benda, the composer’s descendant. Ariadne is about 40 minutes long; if you want a shorter sample, even if the music is not on the same level, here’s a scene from Romeo und Julie. Michael Schneider leads La Stagione Frankfurt and the soloists in a four-minute excerpt from Act III of the opera.

Also, June 26th is the birthday of one of our favorite conductors, Claudio Abbado. He was born 90 years ago in Milan.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: June 19, 2023. Mid-18th Century Music, Watts, and two Conductors. Johann Stamitz, a Bohemian composer and the founder of the so-called Mannheim school, which, with its sudden crescendos and diminuendos, became very popular in the middle of the 18th century, was born on June 18th of 1717. The mid-18th century was a bit short on major talent unless you count Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach who was about three years older than Stamitz (we’re not big fans of CPE Bach but we understand that many people are). Johann Sebastian Bach died in 1750, George Frideric Handel – in 1759, but their music had went out of vogue many years earlier. Domenico Scarlatti, born like the previous two in 1685, was living in Madrid and by then mostly engaged in copying and editing his numerous sonatas; in any event, his output wasn’t well known outside of Spain. In 1750 Joseph Haydn was only 18, so of the living composers there were Telemann, who was getting old and not as productive as in his prodigious youth, and minor stars like Johann Friedrich Fasch and Johann Joachim Quantz. The opera was faring better: Rameau still reigned on the music scene in Paris, and Christoph Willibald Gluck, born the same years as CPE Bach, while not yet on the level of Orfeo ed Euridice, was dispatching operas at the rate of a couple a year. The world had yet to wait for Haydn to develop and for Mozart to appear.

school, which, with its sudden crescendos and diminuendos, became very popular in the middle of the 18th century, was born on June 18th of 1717. The mid-18th century was a bit short on major talent unless you count Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach who was about three years older than Stamitz (we’re not big fans of CPE Bach but we understand that many people are). Johann Sebastian Bach died in 1750, George Frideric Handel – in 1759, but their music had went out of vogue many years earlier. Domenico Scarlatti, born like the previous two in 1685, was living in Madrid and by then mostly engaged in copying and editing his numerous sonatas; in any event, his output wasn’t well known outside of Spain. In 1750 Joseph Haydn was only 18, so of the living composers there were Telemann, who was getting old and not as productive as in his prodigious youth, and minor stars like Johann Friedrich Fasch and Johann Joachim Quantz. The opera was faring better: Rameau still reigned on the music scene in Paris, and Christoph Willibald Gluck, born the same years as CPE Bach, while not yet on the level of Orfeo ed Euridice, was dispatching operas at the rate of a couple a year. The world had yet to wait for Haydn to develop and for Mozart to appear.

Let’s hear one of Johann Stamitz’s symphonies, this one in A major, the so-called “Mannheim no. 2”. Taras Demchyshyn conducts what seems to be mostly the Ukrainian Hibiki Strings ensemble of Japan.

The American composer André Watts was born on June 20th of 1946 in Nuremberg. Watts’s mother was Hungarian and his father – an African-American NCO serving in Germany. Watts spent his childhood in different American military posts in Europe. He started his musical lessons studying the violin and later switched to the piano. At around nine, Watts went to the US and enrolled at the Philadelphia Musical Academy. His breakthrough came in 1963 when he played Liszt’s First Piano Concerto with the New York Philharmonic under the direction of Leonard Bernstein. He later studied with Leon Fleisher at the Peabody Conservatory. From an early age, Watts had a prodigious technique, and his musicianship grew with experience (and studies with Fleisher). His repertoire, while mostly Romantic, was broad. For many years he taught at the Jacobs School of Music of Indiana University. Here’s the 1963 recording of Liszt’s Piano Concerto no. 1 with the NYPO and Leonard Bernstein.

Two conductors were born this week, Hermann Scherchen on June 21st of 1891 in Berlin, and James Levine, on June 23rd of 1943 in Cincinnati. Scherchen was one of the more adventuresome German conductors: he promoted the music of Schoenberg, Berg, and Hindemith after WWI, and conducted Mahler’s symphonies when very few did so. After WWII he was active at Darmstadt and championed the music of Dallapiccola, Henze, and other young composers. He was the first to conduct parts of Schoenberg’s Moses and Aaron.

James Levine was probably the most talented conductor to ever lead the Metropolitan Opera. His place in the musical history of the US would’ve been very different were it not for a sex scandal that broke out in 2017. We’ll dedicate an entry to him shortly.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: June 12, 2023. Maher’s 9th at the CSO. Jakub Hrůša, a Czech conductor, came to Chicago to perform one work, Mahler’s Ninth, his last completed symphony. Any performance of this work by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra is an event, and so was the concert this past Thursday. The CSO doesn’t play the Ninth often: the last performance at the Symphony Center was five years ago, under the direction of Esa-Pekka Salonen, a wonderful Finnish conductor and the current San Francisco Symphony music director. But we vividly remember it being played in December of 1995 when Pierre Boulez led the orchestra in a profound reading. Boulez and the CSO then recorded it at Medinah Temple and received a Grammy for it. Those were the times when Grammys were worth something. By the way, Riccardo Muti, the outgoing Music Director, has never conducted this symphony, or, as far as we know, any other of Mahler’s, except for his youthful no. 1.

Any performance of this work by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra is an event, and so was the concert this past Thursday. The CSO doesn’t play the Ninth often: the last performance at the Symphony Center was five years ago, under the direction of Esa-Pekka Salonen, a wonderful Finnish conductor and the current San Francisco Symphony music director. But we vividly remember it being played in December of 1995 when Pierre Boulez led the orchestra in a profound reading. Boulez and the CSO then recorded it at Medinah Temple and received a Grammy for it. Those were the times when Grammys were worth something. By the way, Riccardo Muti, the outgoing Music Director, has never conducted this symphony, or, as far as we know, any other of Mahler’s, except for his youthful no. 1.

Jakub Hrůša is 41 years old and somewhat of a late-rising star. After conducting several orchestras in his native Czech Republic for several years, in 2016 he was made the chief conductor of the Bamberg Symphony, one of Germany’s better orchestras. The following year he was appointed as one of two principal guest conductors of the Philharmonia Orchestra, London. In 2021 he was made the principal guest conductor of the Orchestra of the Accademia di Santa Cecilia in Rome. Hrůša’s big break came in 2022, when he was appointed the music director designate of the Royal Opera House (the Covent Garden), with the formal appointment as Music Director coming in 2025.

orchestras in his native Czech Republic for several years, in 2016 he was made the chief conductor of the Bamberg Symphony, one of Germany’s better orchestras. The following year he was appointed as one of two principal guest conductors of the Philharmonia Orchestra, London. In 2021 he was made the principal guest conductor of the Orchestra of the Accademia di Santa Cecilia in Rome. Hrůša’s big break came in 2022, when he was appointed the music director designate of the Royal Opera House (the Covent Garden), with the formal appointment as Music Director coming in 2025.

But what about the performance in Chicago? We want to preface our brief assessment with this: we think that no performance by a major orchestra can be bad these days (this was not the case 40 years ago). What we mean is that Mahler’s music contains so much material, both at any given moment and in temporal relation to each other, that even if certain episodes are not done very well, there’s still an enormous amount of substance to overwhelm the listener. For example, under Hrůša’s baton, the opening bars and the first “breathing theme” of the first movement (Andante Comodo) sounded a bit disjointed – maybe nerves and the fact that it was the first of three performances, but it didn’t matter much as things settled down quickly and proceeded wonderfully. The second movement, a series of rustic dances, and the third, Rondo-Burleske, were nervy, sardonic, and at times violent, altogether very well played. We have some qualms with the magnificent final Adagio marked Sehr langsam und noch zurückhaltend (very slowly and reserved). Everything was in place, but somehow not revelatory. This was good, but “good” is not exactly what one expects from this music: Boulez’s finale broke one’s heart. Maybe it’s his younger age and Hrůša will eventually go deeper. The public rewarded the conductor and the musicians with prolonged and enthusiastic applause. The gracious Hrůša went around the orchestra, thanking all the principal players, and then patted the score, indicating the most important element of the proceedings. We thought that to be a very proper gesture: even though the orchestra’s playing was excellent and Hrůša’s interpretation fine, it was Mahler’s genius that made the evening so memorable.

A couple of extraneous points. The Orchestra Hall was full, which is great, considering that Hrůša isn’t that well known in Chicago. As expected, no reviews were published in the major newspapers. Larry Johnson published a nice one in his Chicago Classical Review. And, despite some quibbles, we would be happy if Jakub Hrůša became Muti’s successor.Permalink

The great German Romantic composer Robert Schumann was born on June 8th of 1810, Richard Strauss – on June 11th of 1864. Several other names among the composers born this week: Tomaso Albinoni, once thought of as an equal to Corelli and Vivaldi, on Jun 8th of 1671. Carl Nielsen, Denmark’s by far most famous composer, on June 9th of 1865. The Soviet-Armenian Aram Khachaturian, whose ballets Spartacus and Gayane are still regularly staged in Russia, was born in Tiflis, now Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, on June 6th of 1903 (in those years Tiflis boasted a large Armenian community). Erwin Schulhoff, the Jewish composer, was born in Prague into a German-speaking family on June 18th of 1894. His fate was tragic: his 1941 desperate attempt to escape to the Soviet Union failed; he was

The great German Romantic composer Robert Schumann was born on June 8th of 1810, Richard Strauss – on June 11th of 1864. Several other names among the composers born this week: Tomaso Albinoni, once thought of as an equal to Corelli and Vivaldi, on Jun 8th of 1671. Carl Nielsen, Denmark’s by far most famous composer, on June 9th of 1865. The Soviet-Armenian Aram Khachaturian, whose ballets Spartacus and Gayane are still regularly staged in Russia, was born in Tiflis, now Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, on June 6th of 1903 (in those years Tiflis boasted a large Armenian community). Erwin Schulhoff, the Jewish composer, was born in Prague into a German-speaking family on June 18th of 1894. His fate was tragic: his 1941 desperate attempt to escape to the Soviet Union failed; he was arrested, imprisoned in Bavaria, and died there of tuberculosis in 1942. Schulhoff went through many phases in his life and composed in many styles; his musical progression is quite unique: he started composing atonal pieces, then moved to the Dada, then Romantic, and then, finally (and incredibly) the Social Realism. A couple of years ago we promised to dedicate an entry to him but we’re still not there yet. In the meantime, here is Schulhoff’s Piano Concerto no. 2 (concerto with a chamber orchestra). The pianist is Dominic Cheli; RVC Ensemble is conducted by James Conlon.

arrested, imprisoned in Bavaria, and died there of tuberculosis in 1942. Schulhoff went through many phases in his life and composed in many styles; his musical progression is quite unique: he started composing atonal pieces, then moved to the Dada, then Romantic, and then, finally (and incredibly) the Social Realism. A couple of years ago we promised to dedicate an entry to him but we’re still not there yet. In the meantime, here is Schulhoff’s Piano Concerto no. 2 (concerto with a chamber orchestra). The pianist is Dominic Cheli; RVC Ensemble is conducted by James Conlon.

This Week in Classical Music: June 5, 2023. Schumann and much more. First thing, today is Martha Argerich’s 82nd birthday. Happy Birthday, Martha!

Then there are two conductors, Klaus Tennstedt and George Szell. Szell, born on June 7th of 1897, is considered one of the greatest conductors of the 20th century. We published an entry about him a couple of years ago. Klaus Tennstedt was born on June 6th of 1926 in Merseburg, in the eastern part of Germany which, after WWII, became the GDR. He studied at the Leipzig Conservatory and, in 1958, became the director of the Dresden opera. Tennstedt emigrated from East Germany in 1971. First, he settled in Sweden, where he conducted the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra but a year later moved to West Germany. Tennstedt guest-conducted all major US orchestras and many in Europe, including the Berlin Philharmonic and the Concertgebouw. He was closely associated with two London orchestras, the London Symphony, and London Philharmonic. He became the principal conductor of the latter in 1987. Tennstedt’s interpretations of the music of Mahler were highly acclaimed. Here is the majestic Finale of Mahler’s Symphony no. 3 with the London Philharmonic.

And let’s not forget about Gaetano Berenstadt, a favorite alto-castrato of George Frideric Handel. He was born in Florence on June 6th of 1687. His parents were German, serving at the court of the Duke of Tuscany. Berenstadt first appeared in London in 1717, singing in the operas by Handel, Scarlatti and Ariosti. He then moved to Germany and back to Italy, returning to London in 1722 to join Handel’s Royal Academy of Music. He sang in several of Handel’s operas, including Giulio Cesare, Flavio, and Ottone. Berenstadt returned to Italy for good in 1726; he sang in Rome and Florence for another six years. In bad health for the last few years, he died in Florence at the age of 47.Permalink