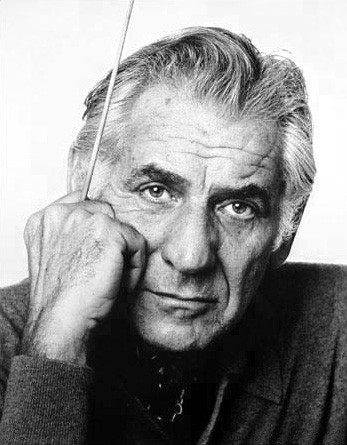

August 20, 2018.Bernstein 100.August 25th will mark the 100th birthday of Leonard Bernstein, American composer, conductor, pianist and music educator.Musical America has been celebrating this event for the past 12 months, and for good reason: Bernstein’s influence on American culture cannot be overestimated.He was one of the most important American composers of the 20th century; his tenure as the music director of New York Philharmonic was probably the most significant in the orchestra’s history.He wrote wonderful musicals, such as Candide and West Side Story, the latter being made world famous when he adapted it to the film (everybody remembers the tunes but it’s worth listening to it again – for all its simplicity it’s amazingly sophisticated music).And of course, his long series of Young People’s Concerts remain one of the great examples of music education: he didn’t condescend to kids, didn’t try to dumb-down the approach (in his very first concert in 1958 he played a piece by Anton Webern) but shared with them his love and understanding of music in his own, communicative and contagiously enthusiastic way.Bernstein was a Renaissance figure, and much was written about him, especially in preparation to the centenary.We’ll address one small aspect of his creative work: the (re)introduction of the music of Mahler into the American culture.Mahler is so ubiquitous these days that it’s hard to imagine that up to the late 1950s his music was rarely heard in concerts.

It’s not quite true that Mahler wasn’t performed at all.Bruno Walter, Mahler’s assistant and friend, programmed his music into some concerts and made several recordings, including Das Lied von der Erde with Kathleen Ferrier and Julius Patzak.

Willem Mengelberg, the Dutch conductor who met Mahler in 1902 and championed his music for the following forty years, did much to promote Mahler’s music in Europe (unfortunately, he was also a Nazi supporter, which didn’t help his legacy).Some years later, John Barbirolli started playing Mahler regularly in Britain.But of the two leading conductors of the 20th century, Arturo Toscanini and Wilhelm Furtwängler, the former never programmed Mahler’s music at all and the latter made just one recording, that ofSongs of a Wayfarerwith Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau.Mahler’s art was at the periphery of the “musical consciousness” and it was Bernstein who moved it firmly into the center, where it has remained ever since.Mahler’s centenary in 1960 was a pivotal moment: celebrating his music Bernstein initiating a yearlong festival.Soon after, in the early 1960s, he recorded all nine symphonies and the Adagio from the unfinished 10th with the New York Philharmonic.Shortly before his death in 1990 he recorded the whole cycle again.In the 1970s, all symphonies were recorded on video; eight symphonies were performed with the Vienna Philharmonic, the Second Symphony was recorded with the London Symphony and Das Lied von der Erde – with the Israel Philharmonic.

In 1960 Bernstein dedicated one of the Young People’s Concerts to Mahler; he called it “Who is Gustav Mahler?”Addressing his audience of children, many as young as eight, he talked about the special affinity he felt toward Mahler: he and Mahler were both composers and conductors, both didn’t have enough time to compose.He talked about the child’s perception of the world that, according to him constitutes the core of Mahler’s music; how his music combined the devastating pessimism with the eternal optimism.Hard to imagine that in our day somebody would talk to kids in these grownup terms.And he played Mahler’s music: from the Second symphony, and from the Fourth, and excerpts from Das Lied von der Erde.He finished that incredible concert with the performance of the last movement of the Symphony no. 4.Here it is, recorded with the same musicians who played for the kids, the New York Philharmonic, and also recorded in 1960.

Bernstein 100 - 2018

August 20, 2018. Bernstein 100. August 25th will mark the 100th birthday of Leonard Bernstein, American composer, conductor, pianist and music educator. Musical America has been celebrating this event for the past 12 months, and for good reason: Bernstein’s influence on American culture cannot be overestimated. He was one of the most important American composers of the 20th century; his tenure as the music director of New York Philharmonic was probably the most significant in the orchestra’s history. He wrote wonderful musicals, such as Candide and West Side Story, the latter being made world famous when he adapted it to the film (everybody remembers the tunes but it’s worth listening to it again – for all its simplicity it’s amazingly sophisticated music). And of course, his long series of Young People’s Concerts remain one of the great examples of music education: he didn’t condescend to kids, didn’t try to dumb-down the approach (in his very first concert in 1958 he played a piece by Anton Webern) but shared with them his love and understanding of music in his own, communicative and contagiously enthusiastic way. Bernstein was a Renaissance figure, and much was written about him, especially in preparation to the centenary. We’ll address one small aspect of his creative work: the (re)introduction of the music of Mahler into the American culture. Mahler is so ubiquitous these days that it’s hard to imagine that up to the late 1950s his music was rarely heard in concerts.

composers of the 20th century; his tenure as the music director of New York Philharmonic was probably the most significant in the orchestra’s history. He wrote wonderful musicals, such as Candide and West Side Story, the latter being made world famous when he adapted it to the film (everybody remembers the tunes but it’s worth listening to it again – for all its simplicity it’s amazingly sophisticated music). And of course, his long series of Young People’s Concerts remain one of the great examples of music education: he didn’t condescend to kids, didn’t try to dumb-down the approach (in his very first concert in 1958 he played a piece by Anton Webern) but shared with them his love and understanding of music in his own, communicative and contagiously enthusiastic way. Bernstein was a Renaissance figure, and much was written about him, especially in preparation to the centenary. We’ll address one small aspect of his creative work: the (re)introduction of the music of Mahler into the American culture. Mahler is so ubiquitous these days that it’s hard to imagine that up to the late 1950s his music was rarely heard in concerts.

It’s not quite true that Mahler wasn’t performed at all. Bruno Walter, Mahler’s assistant and friend, programmed his music into some concerts and made several recordings, including Das Lied von der Erde with Kathleen Ferrier and Julius Patzak.

Willem Mengelberg, the Dutch conductor who met Mahler in 1902 and championed his music for the following forty years, did much to promote Mahler’s music in Europe (unfortunately, he was also a Nazi supporter, which didn’t help his legacy). Some years later, John Barbirolli started playing Mahler regularly in Britain. But of the two leading conductors of the 20th century, Arturo Toscanini and Wilhelm Furtwängler, the former never programmed Mahler’s music at all and the latter made just one recording, that of Songs of a Wayfarer with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. Mahler’s art was at the periphery of the “musical consciousness” and it was Bernstein who moved it firmly into the center, where it has remained ever since. Mahler’s centenary in 1960 was a pivotal moment: celebrating his music Bernstein initiating a yearlong festival. Soon after, in the early 1960s, he recorded all nine symphonies and the Adagio from the unfinished 10th with the New York Philharmonic. Shortly before his death in 1990 he recorded the whole cycle again. In the 1970s, all symphonies were recorded on video; eight symphonies were performed with the Vienna Philharmonic, the Second Symphony was recorded with the London Symphony and Das Lied von der Erde – with the Israel Philharmonic.

In 1960 Bernstein dedicated one of the Young People’s Concerts to Mahler; he called it “Who is Gustav Mahler?” Addressing his audience of children, many as young as eight, he talked about the special affinity he felt toward Mahler: he and Mahler were both composers and conductors, both didn’t have enough time to compose. He talked about the child’s perception of the world that, according to him constitutes the core of Mahler’s music; how his music combined the devastating pessimism with the eternal optimism. Hard to imagine that in our day somebody would talk to kids in these grownup terms. And he played Mahler’s music: from the Second symphony, and from the Fourth, and excerpts from Das Lied von der Erde. He finished that incredible concert with the performance of the last movement of the Symphony no. 4. Here it is, recorded with the same musicians who played for the kids, the New York Philharmonic, and also recorded in 1960.