Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: March 14, 2022. Telemann. Just two weeks ago we complained that it’s difficult to find good music by Antonio Vivaldi other than the overexposed Four Seasons. Vivaldi wrote more than 500 concertos, some of them brilliant (clearly Johann Sebastian Bach thought so, as he transcribed a number of them) but many quite mediocre. The situation with Telemann is even more difficult. Georg Philipp Telemann, who was born on March 14th of 1681 in Magdeburg, was one of the most prolific composers in the history of Western music. He wrote more than 3000 compositions, including 1700 cantatas, of which 1400 are extant. Of course, much of the music was recycled, but Bach did the same on many occasions. How does one go through 1400 cantatas? How many of them have not been performed in the last 100 years? This problem confounds us every time we write about Telemann, and we addressed it directly a couple years ago. Though Telemann was very influential and highly regarded in the 18th century, his fame faded in the 19th, especially when musicologists like Spitta and Schweitzer started unfairly comparing him to Bach, even though during Telemann’s lifetime, and in the following decades, his music was favorably compared to that of Bach and Handel’s. Here is one of Telemann’s cantata’s, Du aber Daniel, gehe hin (Go thy way, Daniel). It is performed by the ensemble Cantus Cölln under the direction of Konrad Junghänel. We find the whole cantata very beautiful, the soprano aria Brecht, ihr müden Augenlieder especially so (it’s sung by Johanna Koslowsky).

Vivaldi wrote more than 500 concertos, some of them brilliant (clearly Johann Sebastian Bach thought so, as he transcribed a number of them) but many quite mediocre. The situation with Telemann is even more difficult. Georg Philipp Telemann, who was born on March 14th of 1681 in Magdeburg, was one of the most prolific composers in the history of Western music. He wrote more than 3000 compositions, including 1700 cantatas, of which 1400 are extant. Of course, much of the music was recycled, but Bach did the same on many occasions. How does one go through 1400 cantatas? How many of them have not been performed in the last 100 years? This problem confounds us every time we write about Telemann, and we addressed it directly a couple years ago. Though Telemann was very influential and highly regarded in the 18th century, his fame faded in the 19th, especially when musicologists like Spitta and Schweitzer started unfairly comparing him to Bach, even though during Telemann’s lifetime, and in the following decades, his music was favorably compared to that of Bach and Handel’s. Here is one of Telemann’s cantata’s, Du aber Daniel, gehe hin (Go thy way, Daniel). It is performed by the ensemble Cantus Cölln under the direction of Konrad Junghänel. We find the whole cantata very beautiful, the soprano aria Brecht, ihr müden Augenlieder especially so (it’s sung by Johanna Koslowsky).

A brief note on two recent concerts. Daniil Trifonov played last week in Chicago. That he is a pianist of huge talent becomes apparent almost immediately. He played a devilishly difficult, dense Szymanowski’s piano sonata no. 3, which seems to be influenced both by Schoenberg in his late tonal phase and Debussy. In Trifonov’s interpretation it became live, floating and very pianistic. Debussy (Pour le Piano) followed and then Prokofiev’s Sarcasms. Ukraine is on our mind: both the Polish Szymanowski and the Russian Prokofiev were born there. The second half of the concert was taken by Brahm’s enormous and somewhat unwieldy 3rd piano sonata. Brahms was just 20 when he wrote it and clearly it’s not his greatest composition but somehow Trifonov made it interesting to listen to. Trifonov is one of the most remarkable pianists on stage today and the concert was exhilarating. As one could’ve guessed, it has not been reviewed in the Chicago Tribune. The good news is that there were many young people in the audience.

A very different concert series took place several days later when Herbert Blomstedt came to town. Blomstedt is 94 and looks his age; he suffers from arthritis and walks slowly. Blomstedt conducted the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in three concerts, with Mozart’s Piano Concerto no. 17 in the first half and Bruckner’s Fourth Symphony in the second. Martin Helmchen was the soloist in the Mozart, and he played well (we’d love to hear him in a recital); Blomstedt held everything together. But of course, the important part came later. The Fourth Symphony is one of Bruckner’s more popular pieces, it’s the one with the famous Scherzo for the third movement. There were some issues in the brass section (is it still the best in the world?) but those were minor. Blomstedt, with his small gestures, managed to propel the symphony forward, despite its many stops, turns and repetitions. All climaxes were thrilling and overall it was a marvelous performance. The score book rested in front of Blomstedt on the stand, its red cover visible. It was never opened: Blomstedt conducted the whole 70-minute symphony from memory. The man is 94! The ovation was long, Blomstedt brought up different sections of the orchestra, all greeted with great applause. At the end Blomstedt patted the score, indicating that it’s Bruckner who should be applauded. How very true. Once again, there were many young people in the hall. Is there still hope for classical music?Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: March 7, 2022. War in Ukraine. We find it very difficult to write about music amidst the barbaric aggression of Russia against Ukraine. Putin’s unprovoked war against a country of 40 million is a watershed moment in European history: there hasn’t been a war of this scale since the fall of the Nazis. Putin clearly is a war criminal: his forces bombard civilian areas, schools, kindergartens, and we hope that, like Slobodan Milošević of Serbia, he will end up at the International Criminal Court in the Hague. The war is a humanitarian catastrophe, and Western response was swift and unified, with sanctions against Russia and aide to Ukraine. Music administrators around the world also got into the game, firing Valery Gergiev, Anna Netrebko and Denis Matsuyev from main stages and theaters of Europe and America after they refused to sign letters condemning Putin’s invasion. While we find these artists’ support of Putin and his regime reprehensible, we are somewhat ambivalent about what seems like a mob action against them. On the one hand we’re glad to see Gergiev gone (we also happen to think that he is overrated as conductor). But Gergiev has been close to Putin for decades. Why didn’t we see any action when Putin illegally annexed Ukrainian Crimea, with Gergiev’s full-throated support? Putin has committed war crimes before: he was the main enabler of Syria’s dictator Assad, and it was his, Putin’s, warplanes that bombed hospitals in Aleppo. Why wasn’t Gergiev fired back then? Is it because Syrian lives matter less than Ukrainian? As for Netrebko, she did support Putin’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine, but it seems that her main fault is that Putin likes her a lot. Netrebko was not the only one who supported Putin back in 2014: more than five hundred (!) Russian cultural luminaries signed a letter in support of the annexation of Crimea, the famous violist Yuri Bashmet and violinist Vladimir Spivakov among them. Since the current war had started, Spivakov and several other signed a meek letter against it, but not Bashmet. Will all “unrepented” musicians be banned from playing in the West? As we noted above, we don’t have a strong opinion about actions against Putin’s artists but find several things troubling. Is it OK to require political loyalty (or, in this case, disloyalty) statements from artists? Why do we treat artist differently, and in a seemingly arbitrary way? Of course, these questions have been asked before, when ardent Hitler’s supporters and Nazi party members Herbert von Karajan and Karl Böhm were quickly denazified and then accepted in the West while clearly not as culpable Wilhelm Furtwängler was not. All this pales compared to the war catastrophe and Putin’s evil, but the question of artists, politics and ethics are important and we’ll have to deal with them in years to come.

war against a country of 40 million is a watershed moment in European history: there hasn’t been a war of this scale since the fall of the Nazis. Putin clearly is a war criminal: his forces bombard civilian areas, schools, kindergartens, and we hope that, like Slobodan Milošević of Serbia, he will end up at the International Criminal Court in the Hague. The war is a humanitarian catastrophe, and Western response was swift and unified, with sanctions against Russia and aide to Ukraine. Music administrators around the world also got into the game, firing Valery Gergiev, Anna Netrebko and Denis Matsuyev from main stages and theaters of Europe and America after they refused to sign letters condemning Putin’s invasion. While we find these artists’ support of Putin and his regime reprehensible, we are somewhat ambivalent about what seems like a mob action against them. On the one hand we’re glad to see Gergiev gone (we also happen to think that he is overrated as conductor). But Gergiev has been close to Putin for decades. Why didn’t we see any action when Putin illegally annexed Ukrainian Crimea, with Gergiev’s full-throated support? Putin has committed war crimes before: he was the main enabler of Syria’s dictator Assad, and it was his, Putin’s, warplanes that bombed hospitals in Aleppo. Why wasn’t Gergiev fired back then? Is it because Syrian lives matter less than Ukrainian? As for Netrebko, she did support Putin’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine, but it seems that her main fault is that Putin likes her a lot. Netrebko was not the only one who supported Putin back in 2014: more than five hundred (!) Russian cultural luminaries signed a letter in support of the annexation of Crimea, the famous violist Yuri Bashmet and violinist Vladimir Spivakov among them. Since the current war had started, Spivakov and several other signed a meek letter against it, but not Bashmet. Will all “unrepented” musicians be banned from playing in the West? As we noted above, we don’t have a strong opinion about actions against Putin’s artists but find several things troubling. Is it OK to require political loyalty (or, in this case, disloyalty) statements from artists? Why do we treat artist differently, and in a seemingly arbitrary way? Of course, these questions have been asked before, when ardent Hitler’s supporters and Nazi party members Herbert von Karajan and Karl Böhm were quickly denazified and then accepted in the West while clearly not as culpable Wilhelm Furtwängler was not. All this pales compared to the war catastrophe and Putin’s evil, but the question of artists, politics and ethics are important and we’ll have to deal with them in years to come.

Several great composers were born this week, among them Maurice Ravel, Arthur Honegger and Hugo Wolf. We’ll get back to them at a later date.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: February 28, 2022. Chopin and Vivaldi. The great Polish composer Frédéric Chopin was born this week, on March 1st of 1810. His works form the core of the classical piano repertoire and have been performed continuously from the moment they were premiered, often by Chopin himself. Musical tastes change in waves, one composer comes to the fore and then recedes only to come back decades later. These days it feels like the music of Chopin with all its full-blooded romanticism is, if not in nadir, then clearly in descent: the time of Arthur Rubinstein, Vladimir Horowitz or the young Maurizio Pollini has passed. But as it has never left the concert stage (and never will), it still has its champions. One of them is a 26-year-old Canadian pianist Jan Lisiecki. He is of the Polish descent and that may have influenced his musical tastes, as in addition to playing a lot of Chopin he promotes the music of Paderewski. Lisiecki clearly feels an affinity with the country of his ancestors, he performs there often and had his first CD issued by the Polish Fryderyk Chopin Institute. He’s one of the very few pianists these days who can build a whole program around the music of Chopin. Recently, he brought one such program to Chicago. It was quite unusual: he played all twelve Etudes, op. 10, but not straight, as they are usually performed, but mixing them with eleven Nocturnes, six Etudes and six Nocturnes in the first half, and six Etudes and five Nocturnes after the intermission. It was an excellent concert: even if one may quibble with some interpretations, Lisiecki clearly has a vision of how this music should be played, he has great technique, wonderful touch and singing tone. Orchestra Hall, the venue where he performed, was full, an unusual occurrence in these Covid days, and, what’s important is that there were many young people in the audience. Lisiecki seems to have a following, and that he’s tall, slim and good looking, reminding one of the young Van Cliburn, clearly doesn’t hurt. There was another matter about this concert worth mentioning: it hasn’t been reviewed by either one of Chicago’s main newspapers. These days it’s not surprising: Chicago Tribune, the home to Claudia Cassidy, and the newspaper that published John von Rhein’s reviews for 40 years, doesn’t even have a music critic on its staff that could credibly write about classical concerts. Kyle MacMillan, whose reviews the Chicago Tribune publishes from time to time, is a free-lance writer. Chicago Sun Times is no different. This attests to the current sorry state of classical music in our society.

of the classical piano repertoire and have been performed continuously from the moment they were premiered, often by Chopin himself. Musical tastes change in waves, one composer comes to the fore and then recedes only to come back decades later. These days it feels like the music of Chopin with all its full-blooded romanticism is, if not in nadir, then clearly in descent: the time of Arthur Rubinstein, Vladimir Horowitz or the young Maurizio Pollini has passed. But as it has never left the concert stage (and never will), it still has its champions. One of them is a 26-year-old Canadian pianist Jan Lisiecki. He is of the Polish descent and that may have influenced his musical tastes, as in addition to playing a lot of Chopin he promotes the music of Paderewski. Lisiecki clearly feels an affinity with the country of his ancestors, he performs there often and had his first CD issued by the Polish Fryderyk Chopin Institute. He’s one of the very few pianists these days who can build a whole program around the music of Chopin. Recently, he brought one such program to Chicago. It was quite unusual: he played all twelve Etudes, op. 10, but not straight, as they are usually performed, but mixing them with eleven Nocturnes, six Etudes and six Nocturnes in the first half, and six Etudes and five Nocturnes after the intermission. It was an excellent concert: even if one may quibble with some interpretations, Lisiecki clearly has a vision of how this music should be played, he has great technique, wonderful touch and singing tone. Orchestra Hall, the venue where he performed, was full, an unusual occurrence in these Covid days, and, what’s important is that there were many young people in the audience. Lisiecki seems to have a following, and that he’s tall, slim and good looking, reminding one of the young Van Cliburn, clearly doesn’t hurt. There was another matter about this concert worth mentioning: it hasn’t been reviewed by either one of Chicago’s main newspapers. These days it’s not surprising: Chicago Tribune, the home to Claudia Cassidy, and the newspaper that published John von Rhein’s reviews for 40 years, doesn’t even have a music critic on its staff that could credibly write about classical concerts. Kyle MacMillan, whose reviews the Chicago Tribune publishes from time to time, is a free-lance writer. Chicago Sun Times is no different. This attests to the current sorry state of classical music in our society.

Antonio Vivaldi was born March 4th of 1678 in Venice. We are on a quest to find great pieces by Vivaldi that are not the Four Seasons. Here’s one of our discoveries, the Intorduzioni, the motets for solo voice, choir and orchestra. There are eight of them altogether, and Canta in Prato, RV 636 is one of them. It consists of three parts, about six minutes of music in total. The English soprano Margaret Marshall is the solo. English Chamber Orchestra and John Alldis Choir are conducted by Vittorio Negri (here).Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: February 21, 2022. Handel and more. George Frideric Handel, one of the greatest composers of the Baroque era, was born on February 23rd of 1685. Interestingly, till about the second half of the 20th century, he was known mostly for his several orchestral works and oratorios, Messiah being the most famous. In reality, Handel was the greatest opera composer of the era and had written music in all genres of the time, including instrumental, chamber and vocal. His reputation is still lower outside of the English-speaking world, where it is on par with Bach’s. We’ve written about Handel many times, here, for example two years ago, with his opera Rodelinda being the focus, and here, about his early years in London. Handel was a fascinating figure, worldly and sophisticated; he was also a virtuoso performer on the keyboard and the violin and wrote for both instruments. Here, for example, is the keyboard Suite in D minor HWV436, it comes from the mid-1720s. It’s performed by the German pianist Ragna Schirmer.

Interestingly, till about the second half of the 20th century, he was known mostly for his several orchestral works and oratorios, Messiah being the most famous. In reality, Handel was the greatest opera composer of the era and had written music in all genres of the time, including instrumental, chamber and vocal. His reputation is still lower outside of the English-speaking world, where it is on par with Bach’s. We’ve written about Handel many times, here, for example two years ago, with his opera Rodelinda being the focus, and here, about his early years in London. Handel was a fascinating figure, worldly and sophisticated; he was also a virtuoso performer on the keyboard and the violin and wrote for both instruments. Here, for example, is the keyboard Suite in D minor HWV436, it comes from the mid-1720s. It’s performed by the German pianist Ragna Schirmer.

Five pianists have anniversaries this week, four of them were Russian-born but none spent their life in Russia: Benno Moiseiwitsch, a British pianist, was born in Odessa, then in the Russian Empire into a Jewish family, on February 22nd of 1890; then three day later is the anniversary of another Brit, this time a “real” one but also Jewish, Dame Myra Hess. Nikita Magaloff, of Russian-Georgian descent who spent much of his life in Switzerland, was born in Saint-Petersburg on February 21st of 1912. Lazar Berman, another Russian (also Jewish), was born on the 26th the month in 1930 in Leningrad (now St.-Petersburg) and, finally, yet another Russian-born pianist, Arcadi Volodos (no, this one is not Jewish) was born on February 24th of 1972, also in Leningrad; these days Volodos lives in Spain. None of these pianists were very interested in the music of Handel, the only example we could find of one of them playing his music is an old, scratchy but interesting recording made in 1937 by the famous Hungarian violinist Joseph Szigeti who was accompanied by Nikita Magaloff. It is Handel’s Violin Sonata in D Major, HWV371, composed later in Handel’s life in 1750 (here).

We also celebrate another Soviet-born musician, a violinist. Gidon Kremer will turn 75 on the 27th, he was born on that day in 1947 in Riga, Latvia. Latvia, now independent, was then part of the Soviet Union; Kremer studied at the Moscow Conservatory with David Oistrakh, became a laureate of several major competitions, and then won the Tchaikovsky Competition in 1970. In 1980 Kremer emigrated from the Soviet Union and settled in Germany. In 1997 Kremer founded a chamber orchestra called Kremerata Baltica. Even though Kramer’s repertoire is very broad (he’s a big promoter of contemporary music), as far as we know he hasn’t recorded a single violin sonata of Handel. So instead we’ll hear Kremer playing a violin sonata by Handel’s contemporary, Johann Sebastian Bach. Here’s Bach Violin Sonata No.3 in C major BWV 1005, written in 1720. The recording was made in 1981.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: February 14, 2022. Kurtág and more. This week brings a bevy of musical talents from several centuries, from Michael Praetoriuswho was born in 1571, probably on February 15th (although some musicologist think he might have been born on September 28th of that year) toFrancesco Cavalli, who was born on this day in 1602, to Arcangelo Corelli, born half a century later, on February 17th of 1653, and then, skipping several well-known names, to the Hungarian composer . It was Kurtág’s name that caught our eye: in five days he will turn 96! But of course it’s not the longevity that makes him special (after all, Elliott Carter lived much longer, to the age of 103): Kurtág is one of the most interesting composers of the 20th century. Here’s an interesting question to ponder: in 100 years, assuming that classical music survives that long as a genre, who would be more popular, Corelli or Kurtág? We think that Kurtág is a much more original composer, but will music lovers internalize and accept the complexities of his music (obviously this is not the case yet). As long as we ventured into the shaky grounds of comparisons, we might as well say that we think that Cavalli was more interesting than Corelli, except for the genre of the early Baroque opera in which he had worked and which is rarely presented these days.

probably on February 15th (although some musicologist think he might have been born on September 28th of that year) toFrancesco Cavalli, who was born on this day in 1602, to Arcangelo Corelli, born half a century later, on February 17th of 1653, and then, skipping several well-known names, to the Hungarian composer . It was Kurtág’s name that caught our eye: in five days he will turn 96! But of course it’s not the longevity that makes him special (after all, Elliott Carter lived much longer, to the age of 103): Kurtág is one of the most interesting composers of the 20th century. Here’s an interesting question to ponder: in 100 years, assuming that classical music survives that long as a genre, who would be more popular, Corelli or Kurtág? We think that Kurtág is a much more original composer, but will music lovers internalize and accept the complexities of his music (obviously this is not the case yet). As long as we ventured into the shaky grounds of comparisons, we might as well say that we think that Cavalli was more interesting than Corelli, except for the genre of the early Baroque opera in which he had worked and which is rarely presented these days.

György Kurtág (his first name is pronounced closer to Dyerd rather than George) was born on February 19th of 1926 in Lugoj, Banat. These days most of the historical Banat lies in Romania, but prior to 1918 Banat was part of the Austro-Hungarian empire; many inhabitants were Hungarian speakers. It also had a large Jewish population; Kurtág is half-Jewish. He spoke Hungarian at home and Romanian at school. As a child, he studied the piano on and off, first with his mother, then with professional teachers. After WWII, in 1946, the 20-year old Kurtág moved to Budapest and continued taking piano lessons, eventually entering the Franz Liszt Music Academy. There he met György Ligeti and they became friends for life. After the Hungarian revolution of 1956, Kurtág moved to Paris. There he studied with Olivier Messiaen and Darius Milhaud. He returned to Hungary in 1959 and stayed there for the duration of the Communist regime – the only Hungarian composer of international renown to do so (Ligeti, for example, fled to Vienna right after the failed revolution and stayed in the West for the rest of his life). At that time Kurtág became influential as a teacher. Surprisingly, he didn’t teach composition but rather interpretation: the pianists Zoltán Kocsis and András Schiff, and the first Takács String Quartet were among his pupils. Kurtág resumed traveling only after the fall of communism in 1989, moving first to Berlin (he was the composer in residence for the Berlin Philharmonic in the mid-90s), then Vienna, the Netherlands and Paris, where he worked with Boulez’s Ensemble Intercontemporain. In 2002, the Kurtágs settled in Bordeaux but in 2015 he and his wife live returned to Budapest (Kurtág’s wife Márta, a pianist, died in 2019).

In addition to Kurtág’s music already in our library, we have two more pieces to illustrate Kurtág’s art. First, a very simple and short piano piece titled ... feuilles mortes ... It’s performed by the Armenian pianist Hayk Melikyan (here). And here is a much more complex …concertante… for violin, viola and orchestra, written in 2003. It’s performed by Hiromi Kikuchi, violin, Ken Hakii, viola and the BBC Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Jukka-Pekka Saraste.Permalink

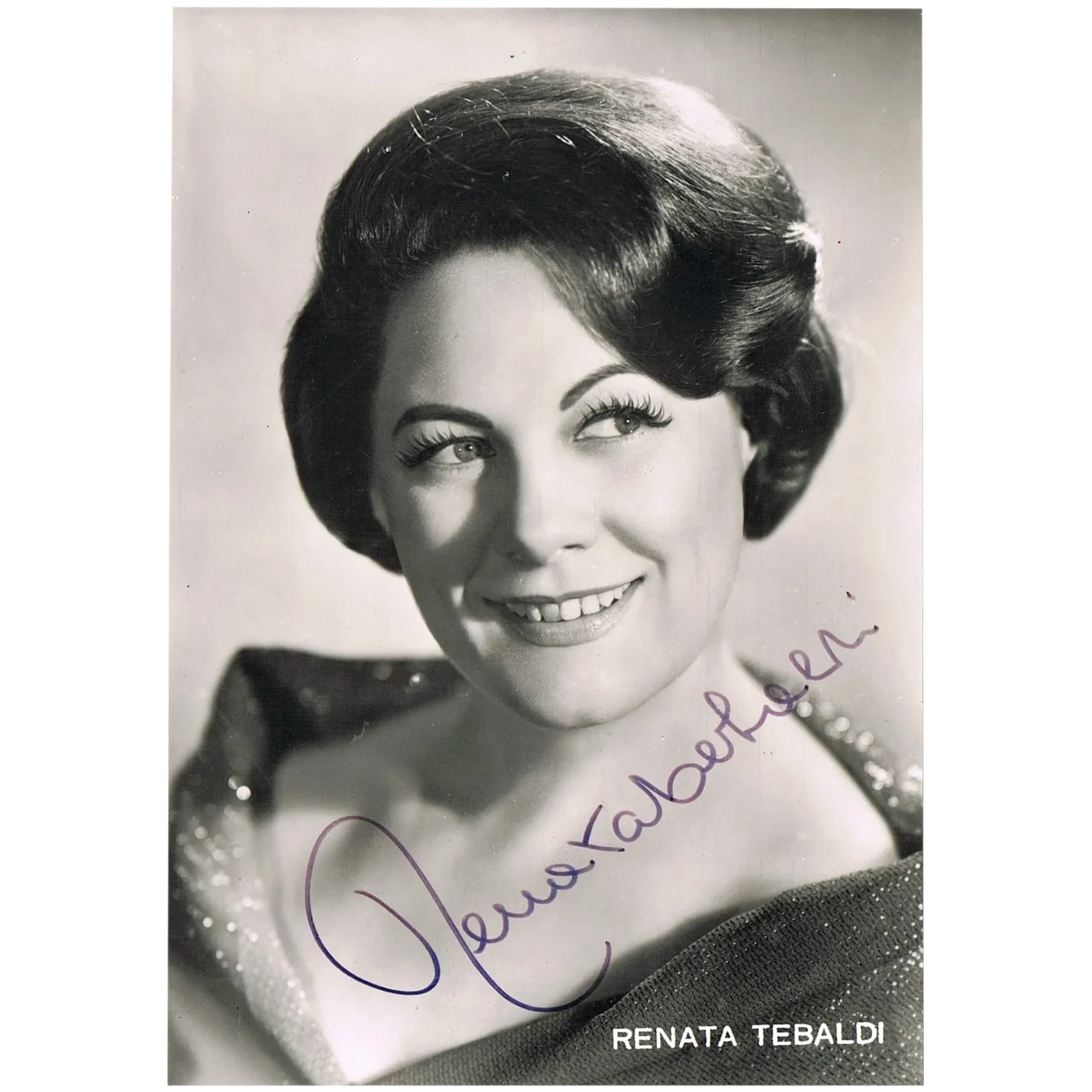

This Week in Classical Music: February 7, 2022. Renata Tebaldi. Last week we missed a very important anniversary: Renata Tebaldi was born 100 years ago! Tebaldi had one of the most beautiful voices of the century, which Toscanini called “the voice of an angel.” She was a rival of Maria Callas, who was a year younger than Tebaldi – it’s hard to imagine that two sopranos of such talent were singing contemporaneously, although Callas’s career was much shorter. It’s difficult to argue that Tebaldi’s voice was more “classical” and in many ways better, although Callas’s had an amazing emotional quality which Tebadli’s interpretations sometimes lacked. Their voices also had somewhat different timbre and range: Callas was a dramatic soprano capable of singing coloratura parties, she was especially good in the bel canto repertoire, while Tebaldi was a lyric soprano at her best in the verismo operas. They shared some roles, Tosca being one of them. Opera lovers will be forever divided between those two divas while adoring them both.

beautiful voices of the century, which Toscanini called “the voice of an angel.” She was a rival of Maria Callas, who was a year younger than Tebaldi – it’s hard to imagine that two sopranos of such talent were singing contemporaneously, although Callas’s career was much shorter. It’s difficult to argue that Tebaldi’s voice was more “classical” and in many ways better, although Callas’s had an amazing emotional quality which Tebadli’s interpretations sometimes lacked. Their voices also had somewhat different timbre and range: Callas was a dramatic soprano capable of singing coloratura parties, she was especially good in the bel canto repertoire, while Tebaldi was a lyric soprano at her best in the verismo operas. They shared some roles, Tosca being one of them. Opera lovers will be forever divided between those two divas while adoring them both.

Tebaldi was born in Pesaro on February 1st of 1922. In 1946 she took part in the opening concert at the war damaged La Scala. The conductor that evening was Arturo Toscanini, and both he and the public loved Tebaldi’s voice. She became a regular at La Scala in the post-war era. In 1950 she sang for the first time at the Covent Garden; the same year she made her debut at the San Francisco opera and then in Chicago. In 1955 she came to New York; she would appear at the Met for the following 20 years. Tebaldi performed till 1976.

As so often is the case with great artists, it’s difficult to select a recording to illustrate their art. Mimi in La Bohème was one of Tebadli’s great roles. Here she is in Si. Mi chiamano Mimi, from the 1959 recording. The Orchestra of Santa Cecilia is conducted by Tullio Serafin. And here is a scene from another opera in which Tebaldi excelled: Pace, pace mio Dio, from Verdi’s La Forza del Destino. This recording was made in 1958 in concert; Leonard Bernstein conducts The New York Philharmonic.

This week and the previous one were rich on singers’ anniversaries: last week we could’ve also celebrated Jussi Björling’s birthday, who was born on February 5th of 1911; this week there are two greats: the soprano Hildegard Behrens who excelled in the German repertoire, from Mozart to Wagner and Berg, and the incomparable Leontyne Price. Behrens was born on February 9th of 1937 and Price – on February 10th of 1927, so she will be celebrating her 95th birthday. Price deserves a full entry, which will be forthcoming. In the meantime, you may be interested to compare Pace, mio dio sung by Tebaldi, above, with Price’s 1984 recording, here.Permalink