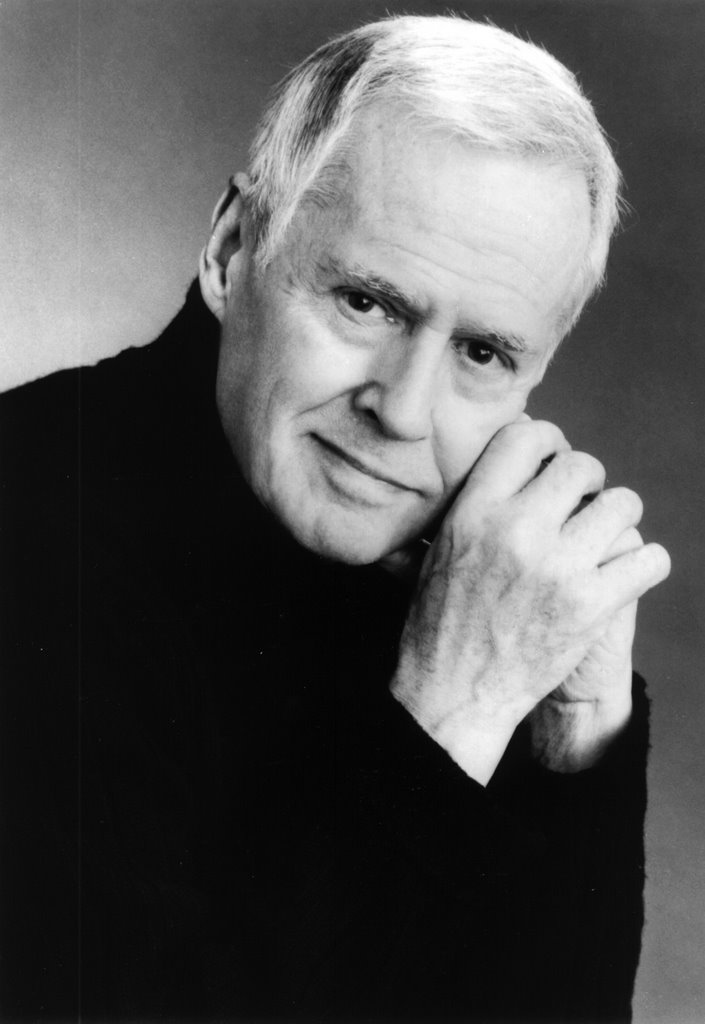

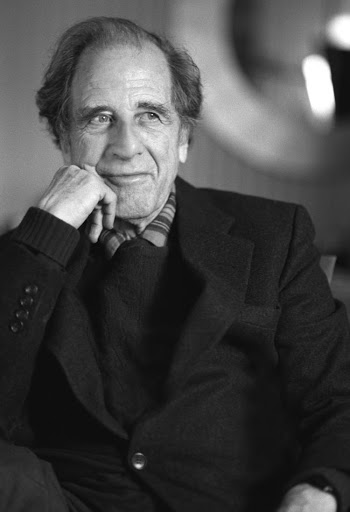

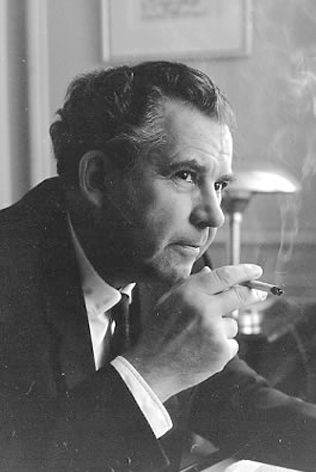

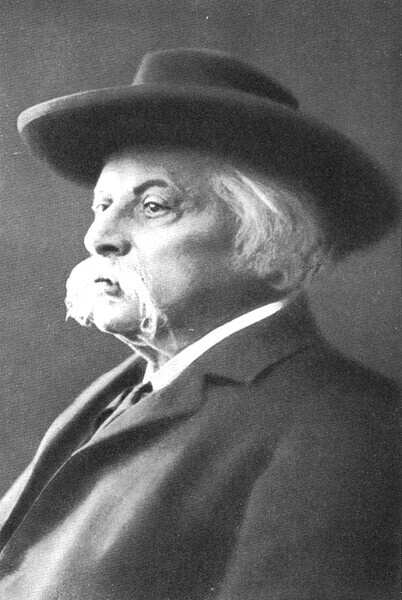

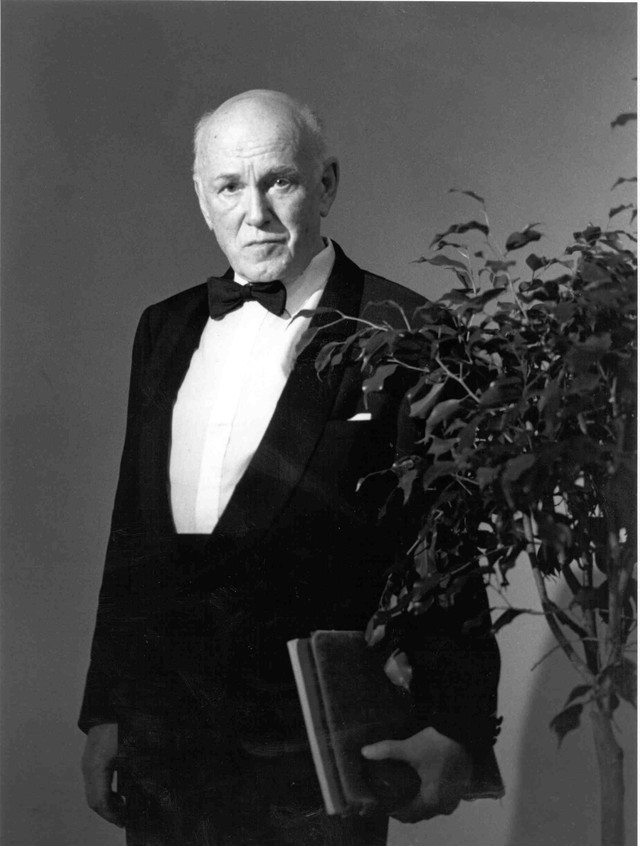

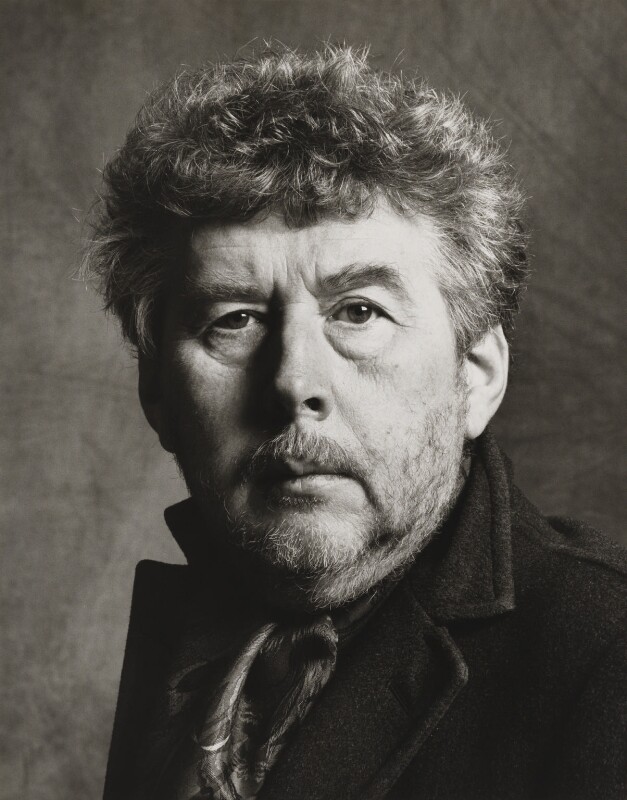

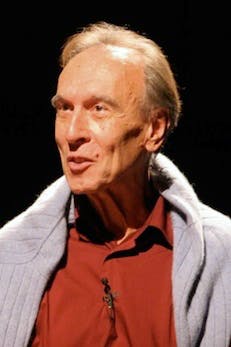

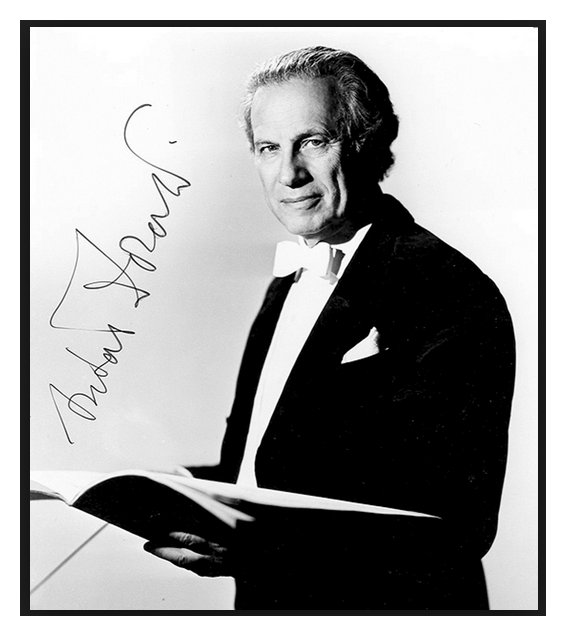

This Week in Classical Music: April 15, 2024. Marriner, Maderna.Sir Neville Marriner, a great English conductor, was born one hundred years ago today, on April 25th of 1924 in Lincoln, UK.He started as a violinist, played in different orchestras and chamber ensembles, and in 1958 founded the Academy of St Martin in the Fields, the chamber orchestra that became world famous.Among Marriner’s friends and founding members were Iona Brown, who led the orchestra for six years from 1974 to 1980, and Christopher Hogwood, who later founded the Academy of Ancient Music.Marriner and St Marin in the Fields made more recordings than any other ensemble-conductor pair. Their repertoire was very broad, from the mainstay of the baroque and classical music of the 18th century to Mahler, Janáček, Stravinsky, Prokofiev and other composers of the 20th.In the words of Grove Music, Marriner’s performances were “distinguished by clarity, buoyant vitality, crisp ensemble, and technical polish.”Altogether, Marriner made 600 recordings, more than any other conductor except for Karajan.In 1969 Marriner co-founded the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, he served as the music director of the ensemble till 1978.Marriner was active till the very end of his life; he died in London on October 2nd of 2016, at 92.

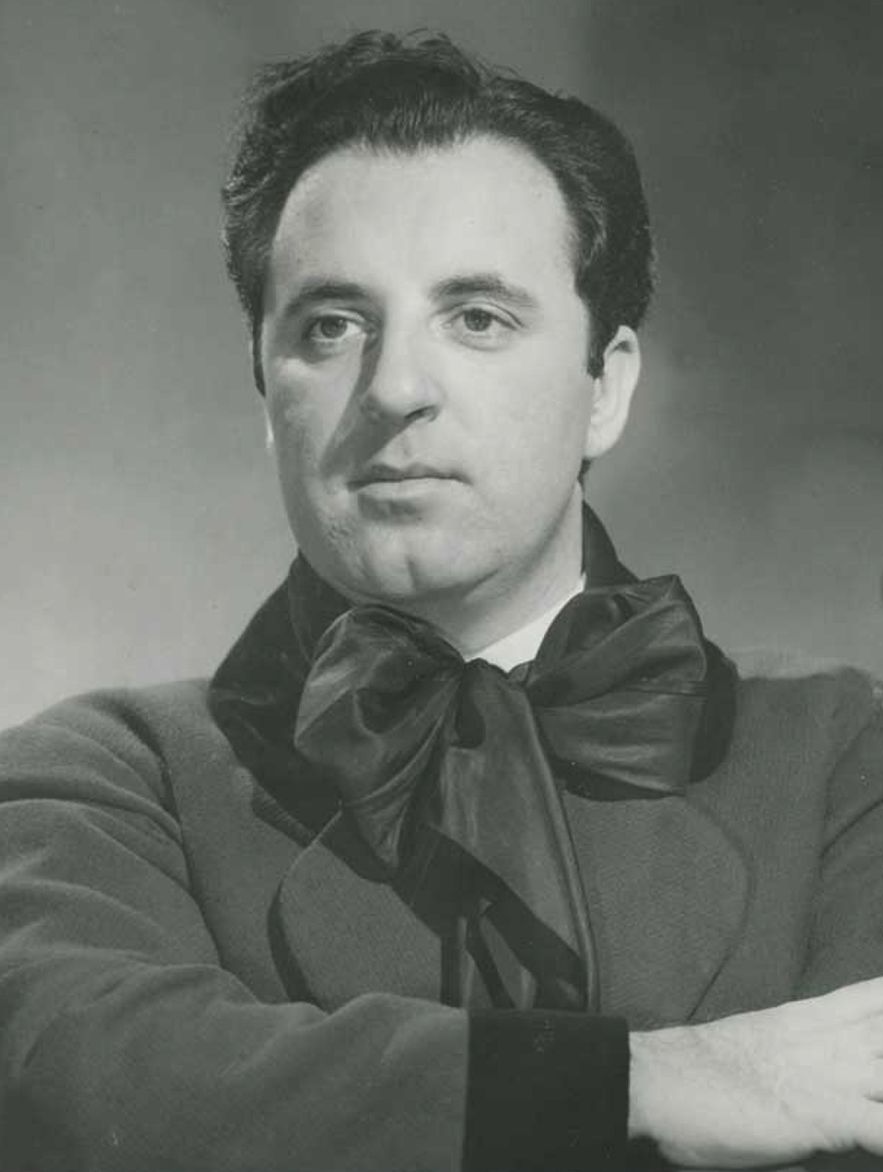

Bruno Maderna, one of the most interesting and influential composers of the 20th century, was born in Venice on April 21st of 1920.Here’s our entry from some years ago.Read more...

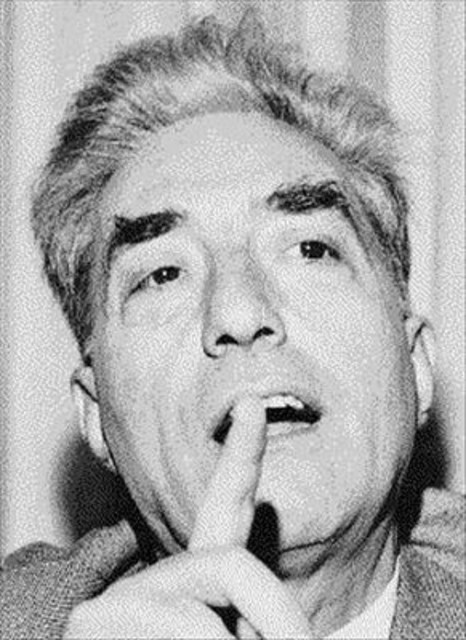

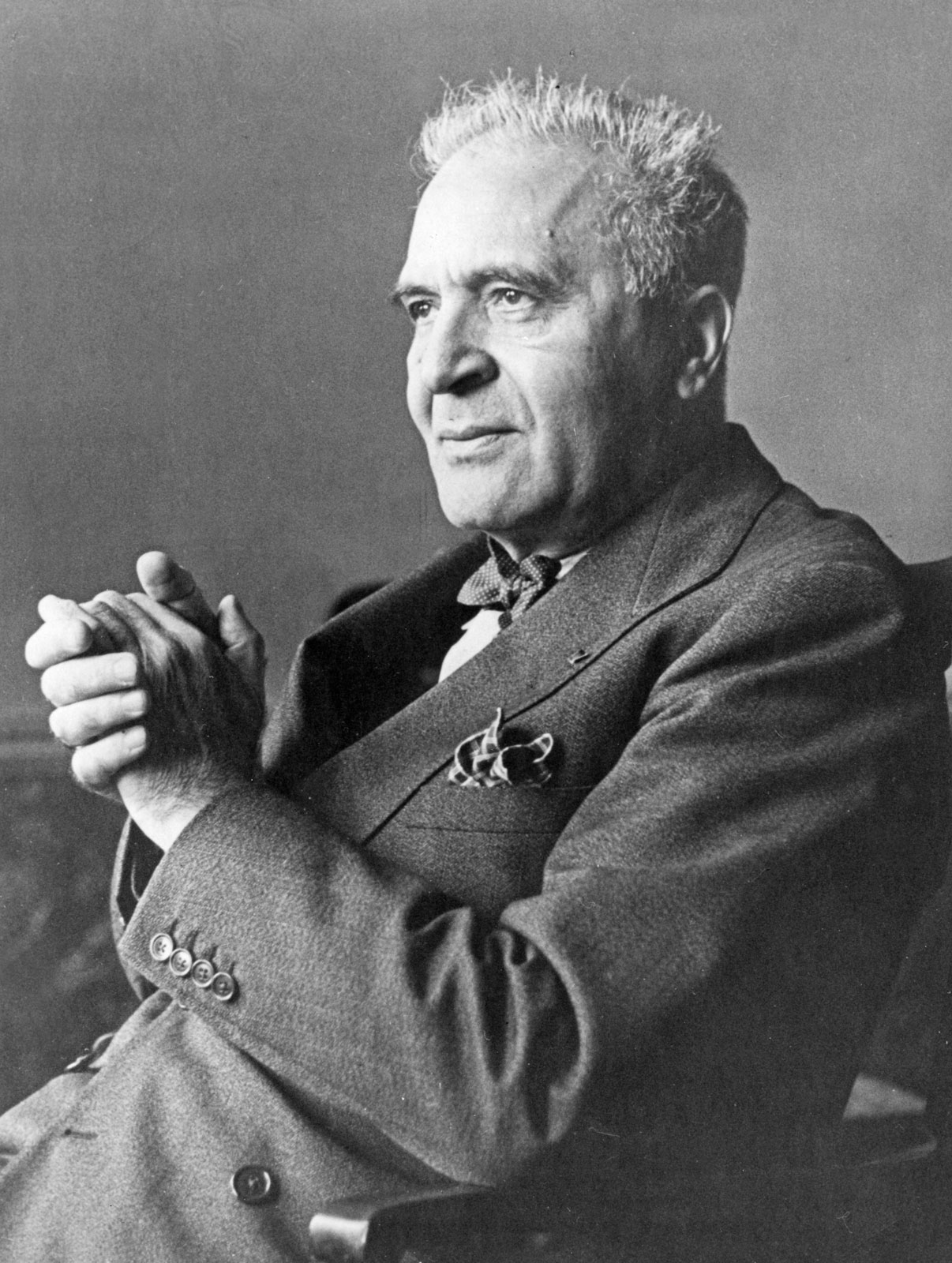

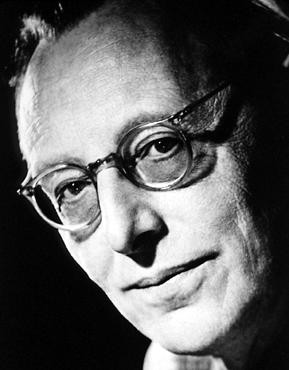

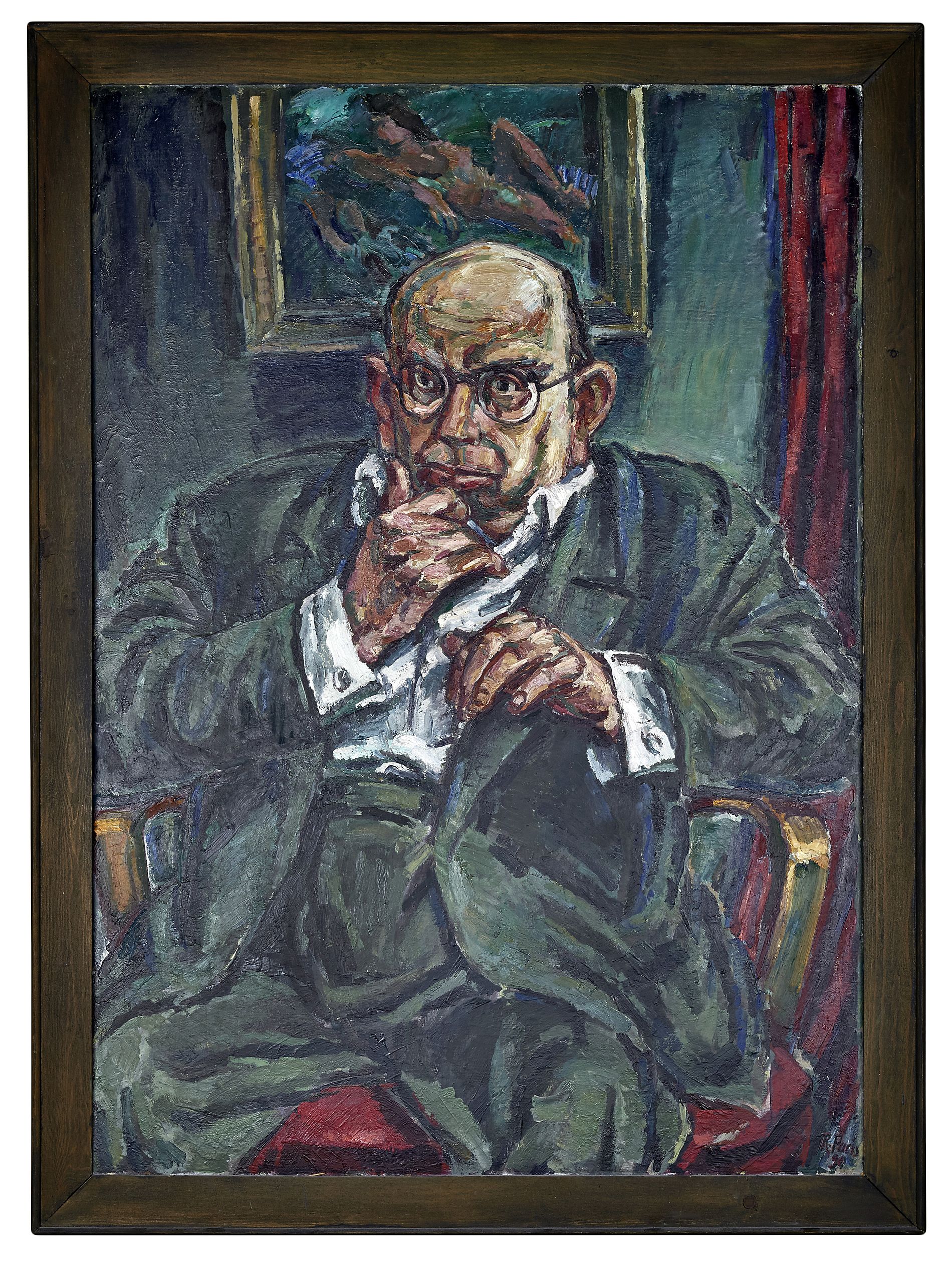

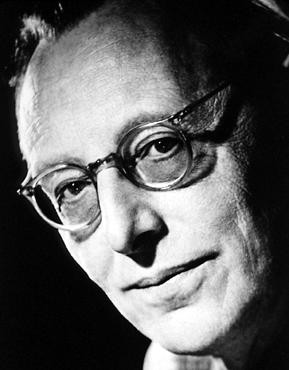

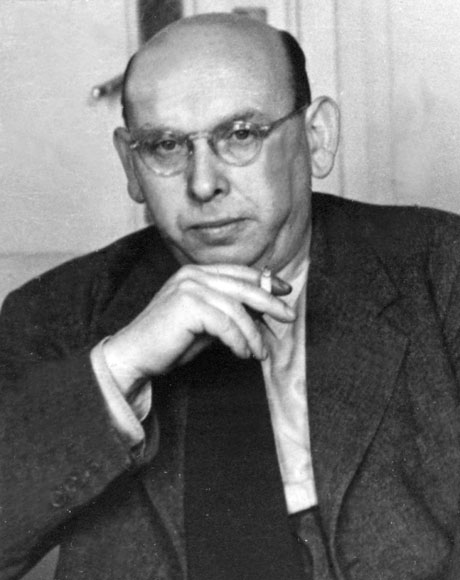

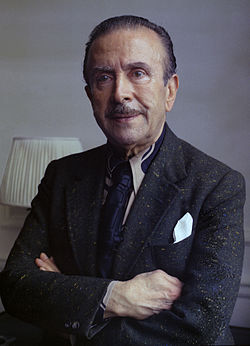

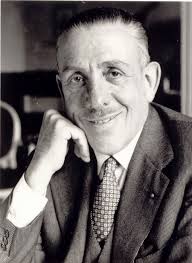

This Week in Classical Music: April 8, 2024. Sol Hurok, Impresario.Hewas neither a musician nor a composer, but Sol Hurok did for classical music in America more than almost any other person we can think of.Hurok was born Solomon Gurkov on April 9th of 1888 in Zarist Russia and moved to New York in 1906.A natural organizer, he started with left-wing politics in Brooklyn; that didn’t last long as he switched to representing musicians: Efrem Zimbalist and Mischa Elman, the talented violinists who also emigrated from Russia, were among his first clients.He represented the Russian bass Fyodor Chaliapin for several years (he also worked with Nellie Melba and Titta Ruffo).He then turned to dance: Anna Pavlova, Isadora Duncan, and Michel Fokine became his clients, as well as the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo.In 1942, he organized one of the first tours of the American Ballet Theatre.

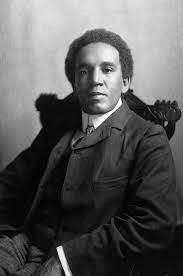

Hurok represented Marian Anderson when working with black singers was not a popular undertaking; he helped to organize Anderson’s famous concert at the Lincoln Memorial, which was broadcast nationwide and made her a household name.Among Hurok’s longest associations were those with Arthur Rubinstein and Isaac Stern.The list of Hurok’s clients read as Who-is-Who in American Music: he worked with the cellist Gregor Piatigorsky, violinists Nathan Milstein and Efrem Zimbalist, and later represented the younger stars, Van Cliburn, Jacqueline du Pré, Itzhak Perlman, and Pinchas Zukerman.

For many years Hurok tried to bring Soviet artists to America.It became possible only after Stalin’s death.The pianists Emil Gilels and violinist David Oistrakh came first, in 1955, then, later, such luminaries as Sviatoslav Richter, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Leonid Kogan and Mstislav Rostropovich.Hurok also represented the singers Galina Vishnevskaya and Irina Arkhipova and conductors Kiril Kondrashin and Yevgeny Svetlanov.Some of Hurok’s greatest coups were achieved with the ballet companies: the Bolshoi tour in 1959 was a sensational success, and so was Kirov’s, which Hurok brought in 1961.

Sol Hurok died in New York on March 5th of 1974.Read more...

This Week in Classical Music: April 1, 2024. Easter Sunday was yesterday.Here is the first chorus of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, "Kommt, ihr Töchter, helft mir klagen" (Come ye daughters, join my lament).Collegium Vocale Gent is conducted by Philippe Herreweghe.

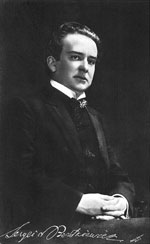

Two composers (great pianists both) were born on this day: Ferruccio Busoni in 1866 and Sergei Rachmaninov in 1873.Read more...

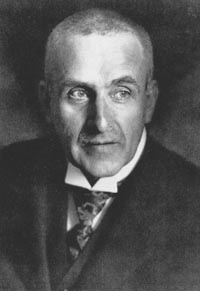

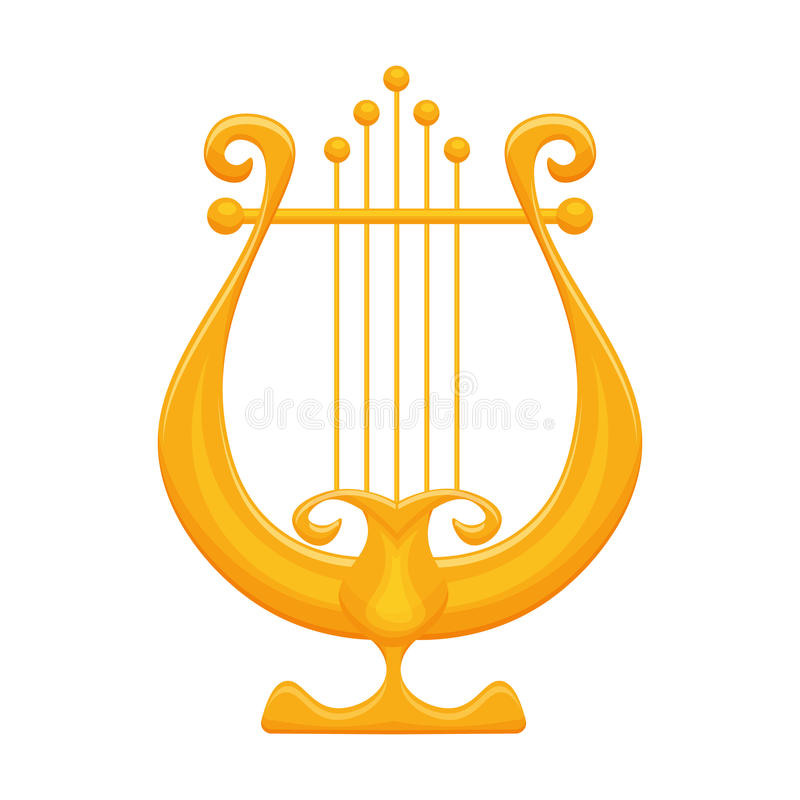

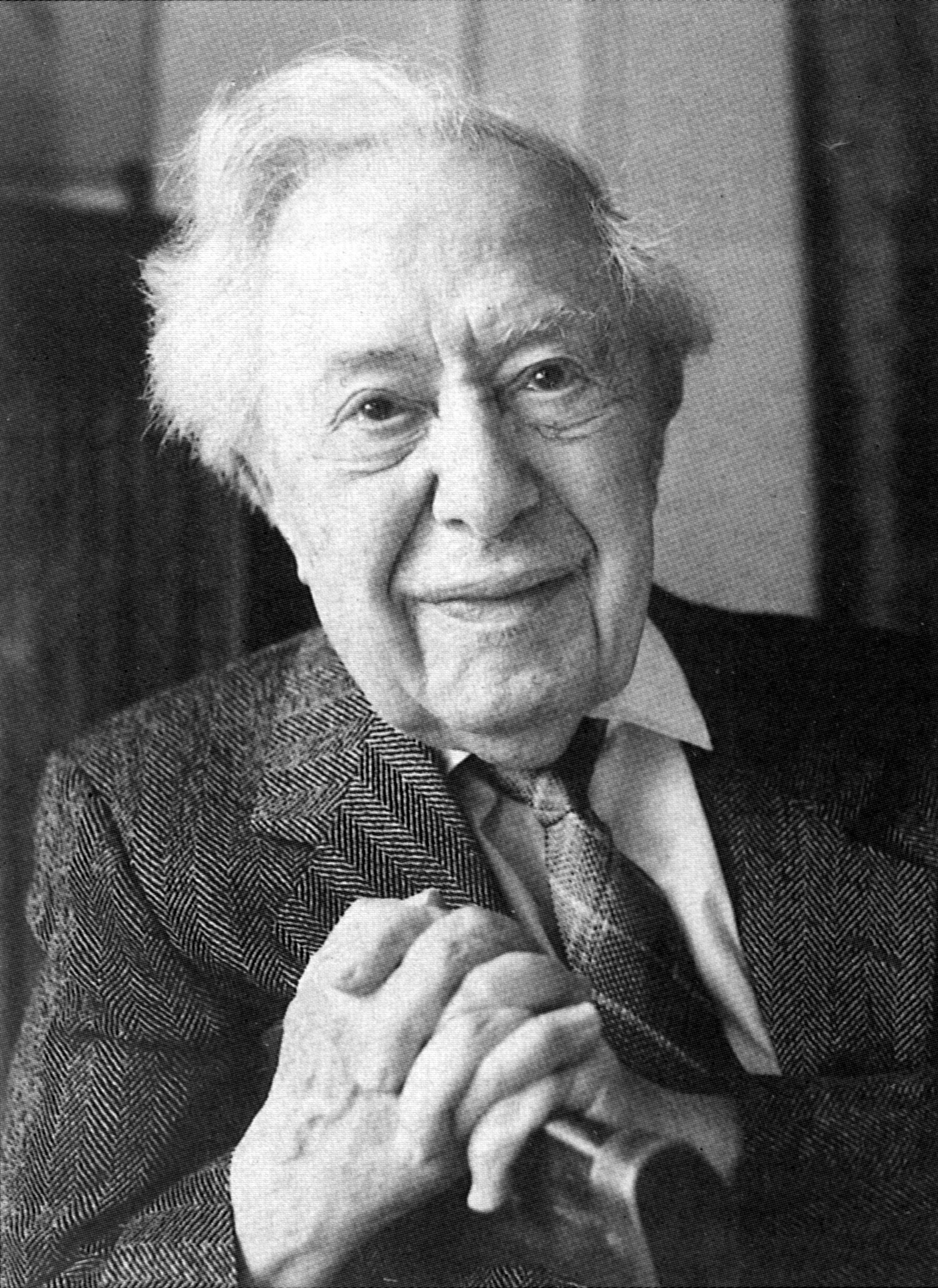

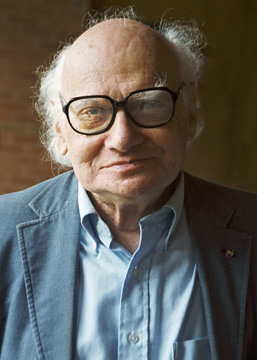

This Week in Classical Music: March 25, 2024. Maurizio Pollini, one of the greatest pianists of the last half century, died two days ago, on March 23rd in Milan at the age of 82.His technique was phenomenal, even though he lost some of it in the last years of his life (he performed almost till the very end of his life and probably should’ve stopped earlier).His Chopin was exquisite (no wonder that he won the eponymous competition in 1960), as was the rest of the standard 19th-century piano repertoire, but he also was incomparable as the interpreter of the music of the Second Viennese School, and even more so as the performer of the contemporary music, much of it written by his friends: Luigi Nono, Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Bruno Maderna, and many other.He will be sorely missed.Speaking of Pierre Boulez: his anniversary is this week as well: he was born on March 26th of 1925.

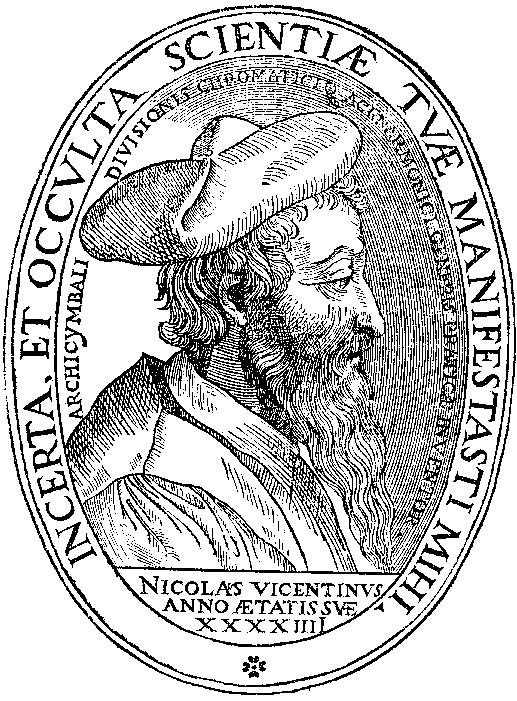

Also this week: Franz Joseph Haydn, born March 31st of 1732; Carlo Gesualdo – on March 30th of 1556; Johann Adolph Hasse, onMarch 25 of 1699; and one of our favorite composers of the 20th century, Béla Bartók, on March 25th of 1881.Read more...

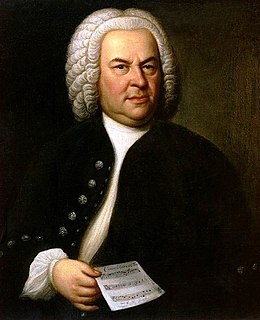

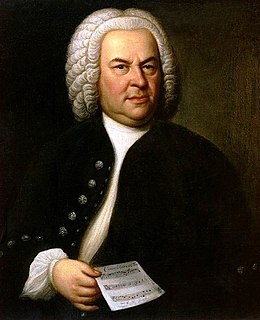

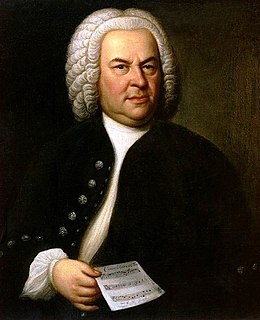

This Week in Classical Music: March 18, 2024. Classical Connect is on a hiatus. Johann Sebastian Bach was born this week, on March 21st of 1685 (old style), in Eisenach.Here is the first part of Bach’s St. John Passion, one of his supreme masterpieces.

This Week in Classical Music: March 4, 2024. Luigi Dallapiccola, Part II. Last week, we ended the story of the Italian composer Luigi Dallapiccola at the beginning of WWII. Mussolini’s fascist state had passed race laws that restricted the civil rights of the Italian Jews, affecting Dallapiccola directly, as his wife was one of them. Later laws would strip the Jews of their assets and send them into internal exile. Italy was no Germany, and these laws weren’t enforced by the Mussolini fascists as they were by the Nazis: no Italian Jews were killed by the regime just because they were Jews (many political opponents of Mussolini were imprisoned and executed, and some of them were Jewish). That state of affairs abruptly changed in 1943 when the Italian army surrendered to the Allies, and in response, the Nazis occupied all of the northern part of Italy. During those years, Dallapiccola and his wife lived in Florence, where he was teaching at the conservatory – Florence was part of the occupied territory. In 1943 and again in 1944, they were forced into hiding, first in a village outside the city, then in apartments in Florence.

Once the war was over, Dallapiccola’s life stabilized. His opera Il prigioniero (The Prisoner), which he composed during the years 1944-48, was premiered in 1950 in Florence (the opera was based in part on the cycle Canti di prigionia, the first song of which we presented in our entry last week). The opera's music was serialist; it was one of the first complete operas in this style, as Berg’s Lulu, the first serialist opera, had not yet been finished. Hermann Scherchen, one of the utmost champions of 20th-century music, conducted the premiere. Despite the music’s complexity, it was often performed in the 1950s and ‘60s. Times have changed, but it’s still being performed, occasionally. Here is the Prologue and the first Intermezzo (Choral) of the opera, about eight minutes of music. It was recorded live in Bologna on April 16th of 2011; Valentina Corradetti is the soprano singing the role of Mother, the orchestra and chorus of the Teatro Comunale di Bologna are conducted by Michele Mariotti.

In 1951, Serge Koussevitzky, the music director of the Boston Symphony and himself a champion of modern music, invited Dallapiccola to give lectures at the Tanglewood Festival. After that first trip, Dallapiccola often traveled to the US, sometimes staying for a long time. Dallapiccola, who spoke English, German and French, also traveled in Europe. Interestingly, he never visited the Darmstadt Summer School, the gathering place for young composers such as Karlheinz Stockhausen, Pierre Boulez, Luigi Nono and Bruno Maderna, who were experimenting with serial music and developing new idioms. It’s especially surprising considering that he was very close to Luigi Nono, and that Luciano Berio, also a Darmstadt habitué, was his former student. It seems that the Darmstadt composers were too cerebral and too radical for Dallapiccola, whose pieces, while strictly serial during that period, were infused with lyricism, somewhat in the manner of one of his idols, Alban Berg.

Dallapiccola’s last large composition was the opera Ulisse, which premiered in Berlin in 1968; Lorin Maazel was the conductor. After that, Dallapiccola composed very little, his time went into adapting some of his lectures into a book. He died on February 19th of 1975 in Florence.

In 1971 Dallapiccolo compiled two suites based on Ulisse. Here is one of them, called Suite/A. The soprano Colette Herzog is Calypso, the baritone Claudio Desderi is Ulysses. Ernest Bour conducts the Chorus and the Philharmonic Orchestra of the French Radio.Read more...

This Week in Classical Music: February 26, 2024. Missed dates and Luigi Dallapiccola. For the last three weeks, we’ve been preoccupied with Alban Berg, and we feel good about it: Berg was a revolutionary composer (not by his constitution but by the nature of his creative talent) and he should be celebrated, even if our time, philistine and woke, doesn’t suit him well. The problem we have is that we missed several very significant anniversaries: for example, George Frideric Handel‘s – he was born on February 23rd of 1685; also, one of the most interesting German composers of the 16th century, Michael Praetorius, was born on February 15th of 1571. We missed the birthday of Francesco Cavalli, a very important composer in the history of opera, on February 14th of 1602. Two famous Italians were also born during those three weeks, Archangelo Corelli on February 17th of 1653 and Luigi Boccherini, on February 19th of 1743. Of our contemporaries, György Kurtág, one of the most important composers of the late 20th century, celebrated his 98th (!) birthday on February 19th. And then this week, there are two big dates: Frédéric Chopin’s anniversary is on March 1st (he was born in 1810) and Gioachino Rossini’s birthday will be celebrated on February 29th – he was born 232 years ago, in 1792. We’ve written about all these composers, about Handel and Chopin many times. Today, though, we’ll remember an Italian whom we’ve mentioned several times but only alongside somebody else; his name is Luigi Dallapiccola, and his story has a connection to Alban Berg.

Luigi Dallapiccola was born on February 3rd of 1904 in the mostly Italian-populated town of Pisino, Istria, then part of the Austrian Empire. Pisino was transferred to Italy after WWI, to Yugoslavia after WWII, as Pazin, and now is part of Croatia. The Austrians sent the Dallapiccola family to Graz as subversives (Luigi, not being able to play the piano, enjoyed the opera performances there); they returned to Pisino only after the end of the war. Luigi studied the piano in Trieste and in 1922 moved to Florence, where he continued with piano studies and composition, first privately and then at the conservatory. During that time, he was so much taken by the music of Debussy that he stopped composing for three years, trying to absorb the influence. A very different influence was Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire, which Luigi heard in 1924 at a concert organized by Alfredo Casella (in the following years, Casella would become a big supporter and promoter of Dallapiccola’s music).

Upon graduation, Dallapiccola started giving recitals around Italy, later securing a position at the Florence Conservatory where he taught for more than 30 years, till 1967 (among his students was Luciano Berio). In 1930 in Vienna, he heard Mahler’s First Symphony, which also affected him strongly: at the time, Mahler’s music was practically unknown in Italy. In the 1930s, Dallapiccola's life underwent major changes. Musically, he became more influenced by the Second Viennese School, and in 1934 got to know Alban Berg (in 1942, while passing through Austria to a concert in Switzerland, he met Anton Webern). The policies of Italy also affected him greatly: first, he was taken by Mussolini’s rhetoric, openly becoming his supporter. This changed with the Abyssinian and Spanish wars, which Dallapiccola protested, and then much more so when Mussolini, under pressure from Hitler, adopted racial (for all practical purposes, antisemitic) policies: Dallapiccola’s wife, Laura Luzzatto, was Jewish. They married on May 1, 1938; the racial laws were adopted in November of that year. Here, from 1938, is the first of the three Canti di Prigionia (Songs of Imprisonment), Preghiera di Maria Stuarda (A Prayer of Mary Stuart) written, in part, as a protest against Mussolini’s racial laws. The New London Chamber Choir is conducted by James Wood, and the Ensemble Intercontemporain, by Hans Zender. We’ll continue with the life and music of Luigi Dallapiccola next week. Read more...

This Week in Classical Music: February 19, 2024. Alban Berg, Part III, Lulu. Frank Wedekind was a famous (and controversial) German playwright. Among his more famous plays

were two, Earth Spirit, written in 1895, and Pandora's Box, from 1904, usually paired together and called Lulu plays, after the name of the protagonist. For a while, the plays were banned for presumed obscenity. Berg saw the plays in the early 1900s in Berlin, with Wedekind himself playing Jack the Ripper in Pandora's Box. He was much taken by the plays, and some quarter century later, following the success of his first opera, Wozzeck, decided to write another one, based on Wedekind’s plays. The storyline of the plays is convoluted: Lulu, an impoverished girl, is saved by a rich publisher, Dr. Schön, from life on the streets. Schön brings her up and makes her his lover. Later, he marries Lulu off to one Dr. Goll. The painter Schwarz gets involved; Lulu seduces him, and poor Dr. Goll dies of a heart attack upon learning of Lulu’s betrayal. Lulu marries painter Schwarz while remaining Dr. Schön’s mistress. Dr. Schön tells Schwarz about Lulu’s past; overwhelmed, Schwarz kills himself. Eventually, Lulu marries Dr. Schön but is unfaithful to him, sleeping with Schön’s son Alwa and other men and women. Once Schön discovers her affairs, he gives Lulu a gun to kill herself - but instead, she shoots him. Lulu is imprisoned at the end of Earth Spirit. In Pandora's Box, Lulu escapes from prison with help from her lesbian lover and marries Alwa, Dr. Schön’s son, (whose father Lulu killed in cold blood). She’s then blackmailed by her former companions and subsequently loses all her money when a certain company’s shares, Lulu’s main asset, become worthless. Lulu and Alwa move to London; destitute, she works as a streetwalker. One of her clients kills Alwa, and eventually, Lulu herself is killed by Jack the Ripper.

By 1929, when Berg started working on Lulu, he was financially secure and quite famous, thanks to the popularity of Wozzeck. He used Wedekind’s Earth Spirit to write the libretto for Act I and part of Act II, and Pandora's Box for the rest of what he planned as a three-act opera. He worked on it for the next five years and mostly completed it in what’s called a “short score,” without complete orchestration, in 1934. By then the Naxis were in power and the cultural situation had changed dramatically. Berg’s position was difficult on two accounts: first, because of the kind of music he was composing (by now not just atonal but 12-tonal) – the Nazis considered it “Entartete,” that is “Degenerate.” And secondly, he was a pupil of a famous Jewish composer, Schoenberg, and that, in the eyes of the regime, tainted him even more. Wozzeck was banned (Erich Kleiber conducted the last performance of the opera in November of 1932), practically none of his music was being performed, and Berg’s financial situation was precarious. In January of 1935, the American violinist Louis Krasner commissioned Berg a violin concerto; financially, that was of great help and the concerto, dedicated to the 18-year-old daughter of Alma Mahler and the architect Walter Gropius, who died of polio, became one of Berg’s most successful compositions.

Understanding that Lulu most likely wouldn’t be staged in Germany – or anywhere else – anytime soon, Berg decided to write a suite for soprano and orchestra based on the opera, the so-called Lulu Suite. Erich Kleiber performed it in November of 1934, it was well received by the public but the level of condemnation by Goebbels and his underlings was such that Kleiber was not only forced to resign from the Berlin Opera but emigrated from Germany. Berg continued working on the orchestration of Lulu but never completed it: in November of 1935 he was bitten by an insect, that developed into a furuncle, which led to blood poisoning. Berg died on Christmas Eve of 1935. In 1979, the Austrian composer Friedrich Cerha completed the orchestration of the third act; this became the standard version of Lulu.

Here is Berg’s Lulu Suite. It’s performed by the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra with Simon Rattle conducting. Arleen Auger is the soprano.Read more...

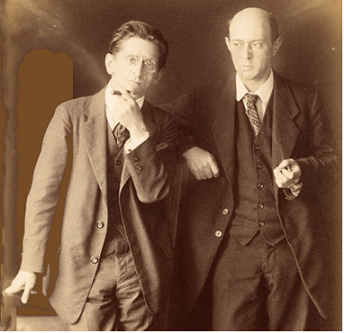

This Week in Classical Music: February 12, 2024. Alban Berg, Part II. In 1911, Arnold Schoenberg moved from Vienna to Berlin but the intense relationship between Berg and his teacher continued through letters. Schoenberg’s notes often contained demands that were about more than just the music: some were domestic, some financial. Though Berg adored his teacher, Schoenberg’s demands were difficult and time-consuming, and the relationship was getting more difficult – so much so that in 1915 their correspondence broke off. WWI was in full swing; Berg was conscripted into the Austrian Army and served for three years (the 42-year-old Schoenberg, who moved back to Vienna in 1915, also served in the army, but only for a year). Things changed in 1918 after Berg was discharged: he returned to Vienna and reestablished his relationship with his teacher.

In May of 1914 Berg attended a performance of Woyzeck, a play by the German playwright Georg Büchner. He immediately decided to write an opera based on the play; it would become known as Wozzeck, a misspelling of the original play’s name that somehow stuck. Berg wrote the libretto himself, selecting 15 episodes from Woyzeck, a macabre story of a poor and desperate soldier, who, suspecting that the mother of his illegitimate child is having an affair with the Captain, murders her, and then drowns. Berg started writing sketches soon after he saw the play but had to stop in June of 1915 when he was drafted. He continued composing while on leave in 1917 and 1918, finished the first act in 1919, the second act two years later, and completed the opera in 1922. It premiered at the Berlin State Opera in December of 1925, with Erich Kleiber conducting. Wozzeck created a scandal, which is understandable, given that it was the first full-size opera written in an atonal idiom, unique not only musically but also in its emotional impact. What is more important (and somewhat surprising) is that the premier was followed by a slew of productions across Germany and Austria. Wozzeck was staged continuously in different German-speaking cities for the next eight years, but also internationally: in Prague, Philadelphia, and even in such an unlikely place as Leningrad. It all came to an end when the Nazis banned it as part of their campaign against Entartete Musik (Degenerate music) and the Austrians dutifully followed. Wozzeck’s success made Berg financially secure, brought him international recognition and some teaching jobs. We’ll listen for the first 15 minutes of Act II of Wozzeck. In Scene 1, Marie puts her son to bed, then Vozzeck arrives, gets suspicious of her earrings (they were given to her by the Captain), gives her some money and leaves. In Scene 2, the Doctor and the Captain walk the street; they see Wozzeck, make fun of him and insinuate that Marie isn’t faithful. Wozzeck runs away in despair. Claudio Abbado conducts the Orchestra and Chorus of the Vienna State Opera (we know the orchestra as the Vienna Philharmonic); Wozzeck is sung by Franz Grundheber, his common-law wife Marie is Hildegard Behrens. Heinz Zednik is the Captain, Aage Haugland is the Doctor.

Wozzeck was an atonal opera, but it wasn’t a 12-note composition, the technique which by then was being developed by Schoenberg. Berg was receptive to it and soon moved in a similar direction. He wrote two pieces, Kammerkonzert (Chamber Concerto for Piano and Violin with 13 Wind Instruments), completed in 1925, and Lyric Suite, a year later, which broadly used the 12-tone technique. In 1929 he started work on his second major opera, Lulu, a much larger and more complex composition than Wozzeck. We’ll cover it next week, in our the third and final installment on Berg.Read more...

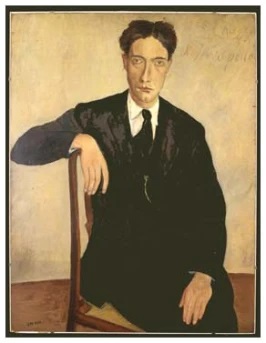

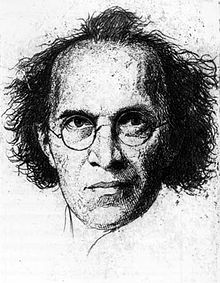

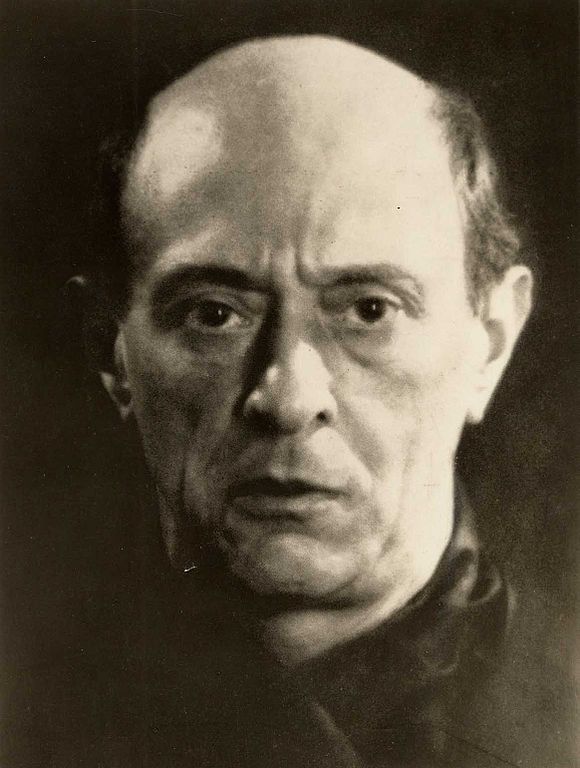

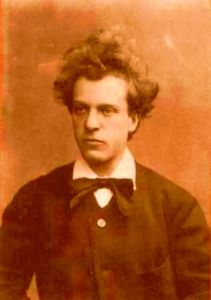

This Week in Classical Music: February 5, 2024. Berg, Part I, Early Years.Alban Berg, a seminal German composer of the first half of the 20th century, was born in Vienna on February 9thof 1885. Berg, with Anton Webern, was a favorite pupil of Arnold Schoenberg and was one of the first composers to write atonal and 12-tonal music. While Schoenberg was often cerebral, even in his more expressive works and Webern a much stricter follower of the technique in his succinct, perfectly formed pieces, Berg’s music was more lyrical and Romantic, even as he abandoned the tonal format. Berg’s background was very different from his Jewish teacher’s: his Viennese family was well-off, at least while his father was alive (he died when Alban was 15), they lived in the center of the city (Schoenbergs lived in Leopoldstadt, a poor Jewish neighborhood). Berg was a poor student: he had to repeat the 6th and the 7th grades. Even though Alban was interested in music from an early age and wrote many songs, he clearly wasn’t suited for studies in a formal environment and lacked the required qualifications, so, instead of going to a conservatory he became an unpaid civil servant trainee. In 1904, without any previous musical education, he became Schoenberg’s student. By that time Schoenberg, who was struggling financially and took students to support himself, had already written Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night) and a symphonic poem Pelleas und Melisande. Both had a fluid tonal canvass as Schoenberg was already researching the atonal idiom, but it would be another three years till he’d write his Quartet no. 2, his first truly atonal piece; all these developments took place while Berg was his student. Berg studied with Schoenberg till 1911, first the counterpoint and music theory, and later composition. During that time he sketched several piano sonatas and later completed one of them, published as his op. 1. That was a big departure, as before joining Schoenberg all he could write were songs.

We should note that the pre-WWI years in Vienna were a period of tremendous cultural development; despite the overall antisemitism of the Austrian society, many of the leading figures were Jewish, and sexuality was explored deeply for the first time. In music, it was Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, Alexander von Zemlinsky, Schoenberg, Franz Schreker, Egon Wellesz, Ernst Toch, and of course, Webern and Berg, with many younger composers to follow. Arthur Schnitzler, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Robert Musil and Stefan Zweig were important novelists and playwrights (Frank Wedekind, their German contemporary, was the source for Berg’s opera Lulu). The painter Gustav Klimt was Berg’s friend, and so was the architect Adolf Loos. And we shouldn’t forget Sigmund Freud, who was not just a psychoanalyst famous around Vienna but a leading cultural figure.

A characteristic episode happened in March of 1913 when Schoenberg conducted what became known as the Skandalkonzert ("scandal concert") in Vienna’s Musikverein. Here’s the program: Webern: Six Pieces for Orchestra; Zemlinsky: Four Orchestral Songs on poems by Maeterlinck; Schoenberg: Chamber Symphony No. 1; Berg: Two of the Five Orchestral Songs on Picture-Postcard Texts by Peter Altenberg. Mahler's Kindertotenlieder was supposed to be performed at the end, but during the performance of Berg’s songs fighting began and the concert was cut short. The Viennese public’s response could be expected, if not necessarily in its physical form (after all, their favorite music was Strauss’s waltzes), but how many American presenters would dare to program such a concert in our time, more than 100 years later? We can listen to Berg’s songs that were performed during the concert, no. 2 of op. 4 here and no. 3 here. The soprano is Renée Flemming; Claudio Abbado leads the Lucerne Festival Orchestra.

We’ll continue with Berg and his two masterpieces, operas Wozzeck and Lulu, next week. Read more...

This Week in Classical Music: January 29, 2024. Schubert, Mendelssohn and more. What an exceptional week: Franz Schubert was born on January 31st of 1797, and February 3rd is the anniversary of Felix Mendelssohn, born 12 years later, in 1809. We just celebrated Mozart’s birthday; he died very young, at 35. Schubert’s life was even shorter: he was 31 when he passed away, and Mendelssohn – only 38. All three could’ve lived twice as long, and our culture would’ve been so much richer. Schubert is one of our perennial favorites (tastes and predilections change, Schubert stays) and we’ve written many entries about him (here and here, for example), including longer articles on his song cycles. There are hundreds of his pieces in our library – he remains one of the most often performed composers. His life was not eventful, his music was sublime, so here’s one of his songs: An die Musik, that is, To Music that Schubert composed in March of 1817 (he was twenty). Nothing can be simpler and more beautiful. We could not select a favorite recording, there are too many excellent ones, so we present three, all sung by the Germans: soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf with the great pianist, Edwin Sicher, released in 1958 (here); the 1967 recording made by the baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau with Roger Moore (here); and Fritz Wunderlich, an amazing tenor who also died at 35, accompanied by Hubert Giesen in a 1967 recording (here). You can decide for yourself which one you like better.

As for Mendelssohn, his most famous “songs” were not vocal butfor piano solo:Songs without Words. Still, he also composed “real” songs – not as many as Schubert, of course, who wrote about 600 – and some of them are wonderful.Here, for example, is Gruss (Greeting), a song from his op. 19a on a poem by Henrich Heine. It’s performed by the Irish tenor Robin Tritschler, accompanied by Malcolm Martineau. When he wrote his songs op. 19a, Mendelssohn wasn’t much older than Schubert of An die Musik: he started the cycle at the age of 21.

Three Italian composers were also born this week: Alessandro Marcello, on February 1st of 1673, Luigi Dallapiccola, on February 3rd of 1904, and Luigi Nono, on January 29th of 1924. We’ve never written about Dallapiccola even though he was a very interesting composer; we’ll do it next week.

Also, yesterday was Arthur Rubinstein’s birthday (he was born in 1887, 137 years ago, but his ever-popular recordings evidence that he was one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century). Two wonderful singers were also born this week, the Italian soprano Renata Tebaldi on February 1st of 1922, and the Swedish tenor Jussi Björling, one of the few non-Italians who could sing Italian operas as well as the best of the locals, on February 5th of 1911.Read more...

This Week in Classical Music: January 22, 2024. Mozart. The main event of this week is Mozart’s birthday, on January 27th.Wolfgang Amadeus was born in 1756 in Salzburg.One of the greatest composers in history, he excelled in practically every genre of classical music.His operas are of the highest order (just think of the Magic Flute, Don Giovanni, the Marriage of Figaro, or Così fan tutte, but then there are several operas, though not as popular, such as La clemenza di Tito, The Abduction from the Seraglio, or Idomeneo, that would make any other composer proud).His symphonies are the pinnacle of the orchestral music of the Classical period, and so are his piano concertos.His violin concertos were written when he was very young (the last one, no. 5, “Turkish” was completed when Mozart was 19) but were already very good.He wrote many piano sonatas that predate Beethoven’s, and wonderful violin sonatas (he was a virtuoso performer of both instruments).And then there is his chamber music: trios, quartets for all combinations of instruments, not just the strings, quintets, and much more.He did all that in just 35 years.In addition to the “standard” piano and violin concertos, Mozart wrote concertos for many different wind instruments: the horn (four of them), bassoon, flute, oboe, and clarinet.His Clarinet concerto in A major, K. 622 is marvelous.It’s a late piece, late, of course, in Mozart’s terms – he was 35 in 1791 when it was completed, less than two months before his death of still unknown causes (one thing we know for sure is that he has not been poisoned by Antonio Salieri): Mozart was already quite ill while working on the concerto.The concerto was written for Anton Stadler, a virtuoso clarinetist and a close friend of Mozart’s (they had known each other since 1781) for whom he also wrote his Clarinet Quintet.Stadler invented the so-called basset clarinet, a version of the instrument that allows the performer to reach lower notes, and that was the instrument for which Mozart wrote the concerto.We’ll hear it performed by a talented German clarinetist Sabine Meyer with the Staatskapelle Dresden under the direction of Hans Vonk.

Muzio Clementi, who competed as a keyboard player and composer with Mozart at the court of Emperor Josef II, was born on January 23rd of 1752.He, Henri Dutilleux, Witold Lutoslawski, the pianists Josef Hofmann, John Ogdon and Arthur Rubinstein, the cellist Jacqueline du Pré and Wilhelm Furtwängler, a great conductor, all of whom were born this week, will have to wait for another time.Read more...

This Week in Classical Music: January 15, 2024. Schein and much more. Several composers were born this week: Niccolò Piccinni (b. 1/16/1728), a nearly forgotten Italian composer who was famous in his day for his Neapolitan opera buffa; Cesar Cui (b. 1/18/1835), a Russian composer of French descent (his father entered Russia with Napoleon) and a member of the Mighty Five; Emmanuel Chabrier (b. 1/18/1841), a mostly self-taught French composer, whose España is his best-known symphonic work but who also wrote some very nice songs; Ernest Chausson (b. 1/20/1855), another Frenchman, who wrote the Poème for the violin and orchestra which entered the repertoire of all virtuoso violinists; Walter Piston (b. 1/20/1894), a prolific and prominent American composer of the 20th century who often used Schoenberg’s 12-note method; Alexander Tcherepnin (b. 1/20/1899), a Russian composer who was born into a prominent musical family (his father, Nikolai Tcherepnin was a noted composer and cultural figure), left Russia after the 1917 Revolution, settled in France, moved to the US after WII and had several symphonies premiered by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra; and, finally, another Frenchman, Henri Duparc (b. 1/21/1848), best known for his art songs.None of these composers were what is usually called “great” but all were talented and some of their works are very interesting.Listen, for example, to Alexander Tcherepnin’s 10 Bagatelles, op. 5 in a version for piano and orchestra (here).Margrit Weber is at the piano, Ferenc Fricsay conducts the Radio-Symphonie-Orchester Berlin.Or, in a very different way, here’s Duparc’s fine song, L'invitation au Voyage.Jessye Norman is accompanied by Dalton Baldwin.

One composer, also born this week, interests us more than all the above, even though his name is almost forgotten- Johann Hermann Schein.Schein, a good friend of the better-known Heinrich Schütz, was one of the most important German composers of the pre-Bach era.He was born on January 20th of 1586 (99 years before Bach) in Grünhain, a small town in Saxony.As a boy, he moved to Dresden where he joined the Elector’s boys’ choir; there he also received thorough music instruction.In his twenties, on the elector’s scholarship, he studied law and liberal arts at the University of Leipzig.He published his first collection of madrigals and dances, titled Venus Kräntzlein, in 1609.Starting in 1613 he occupied several kapellmeister positions, starting in smaller cities, till 1616, when he was called to Leipzig.He passed the audition and was accepted as the Thomaskantor, the most senior position in the city and the one Bach would assume 107 years later.Like Bach a century later, he was responsible for the music at two main churches, Thomaskirche and the Nicolaikirche, and for teaching students at the Thomasschule.Schein held the position of Thomaskantor for the rest of his life, which, unfortunately, was short: in his later years, he suffered from tuberculosis and other maladies and died at the age of 44 (Heinrich Schütz visited him on his deathbed).

Here's Schein’s motet, Drei schöne Ding sind (Three beautiful things), performed by the Ensemble Vocal Européen under the direction of Philippe Herreweghe.And here’s another motet, Ist nicht Ephraim mein teurer Sohn (Isn't Ephraim my dear son?), performed by the same musicians.Read more...

This Week in Classical Music: January 8, 2024. Catching up. Last week we simply wished you a happy New Year, so this week we’ll try to make up for it and cover the first two weeks of the year. January 5th should be officially named Piano Day, as on this day three great pianists were born: Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, in 1920, Alfred Brendel, in 1930, and Maurizio Pollini, in 1942. Pollini still performs, but we stopped attending his concerts some years ago: he’s now just a shadow of his great self. This doesn’t diminish his prodigious talent that he brilliantly displayed for decades with virtuosity and incisive repertoire, which, unique to a pianist of his stature, included the music of many modern composers. (In comparison, the repertoire of his compatriot, the perfectionist Michelangeli, was very narrow).

Two prominent Soviet cellists were born during these two weeks, Sviatoslav Knushevitsky, on January 6th of 1908, and Daniil Shafran, on January 13th of 1923. Knushevitsky is not well known outside of Russia but in his day, he was considered one of the very best (in the rank-obsessed Soviet Union, he was the third best cellist, after Rostropovich and Shafran; had he not drunk, he might have been number one). In 1940, Knushevitsky, David Oistrakh and Lev Oborin organized a very successful trio; they performed worldwide to great acclaim. Knushevitsky and Oistrakh also played together in one of the incarnations of the Beethoven quartet. Knushevitsky died at the age of 55 from a heart attack, alcoholism probably contributing to his early death. Here’s the famous second movement from Schubert’s Piano Trio no. 2, which Stanley Kubrick used so effectively in his Barry Lindon. It’s performed by David Oistrakh, violin, Sviatoslav Knushevitsky, cello, and Lev Oborin, piano. The recording was made in 1947. You can also find the complete Triohere. And here, from 1950, is Sviatoslav Knushevitsky’s recording of Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations. Alexander Gauk leads the Great Radio Orchestra. As for Shafran, you can read more about him in one of our earlier entries.

Another Russia-born string player has an anniversary this week: Nathan Milstein, one of the greatest violinists of the 20th century. Odessa, where Milstein was born on January 13th of 1904, was back then part of the Russian empire. Now, spelled Odesa, it is in free Ukraine, being bombed by Russia almost daily. Speaking of Russia, Aleksander Scriabin was born on January 6th of 1872 in Moscow. His early piano pieces were charming imitations of Chopin’s but later he developed a musical language all his own, with a very fluid tonality, if not quite atonal. His grandiosity, both personal and musical, and his attempts to synthesize music and color didn’t age well (especially in his orchestral output), but his piano music is still played very often and is of the highest quality.

Among other anniversaries: Francis Poulenc’s 125th was celebrated on January 7th (he was born in 1899). Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, who died tragically young, aged 26, from tuberculosis, but left us a tremendous Stabat Mater and a brilliant intermezzo La serva padrona (Sonya Yoncheva is great as Serpina in this production), was born in a small town of Jesi, Italy, on January 4th of 1710.Read more...

This Week in Classical Music: January 1, 2021. Happy New Year!

This Week in Classical Music: December 25, 2023. Christmas. We wish our listeners a Merry Christmas!On this wonderful day, we won’t bother you with disquisitions and analyses but will present some Christmas music for your pleasure – and this joyful piece is perfect for the occasion.It’s the first section of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Christmas Oratorio, a cantata known for the initial words of the first chorus as Jauchzet, frohlocket! (Shout for joy, exult).It was first performed on this day in 1734, in the morning, at St. Nicholas; and then in the afternoon, at St. Thomas in Leipzig: Bach, as Thomaskantor, was the music director of both churches and led both performances.What we will hear is a recording made in January of 1987 by John Eliot Gardiner conducting the English Baroque Soloists and Monteverdi Choir and several prominent soloists, Anne-Sophie von Otter among them.Enjoy and see you in 2024!Read more...

This Week in Classical Music: December 18, 2023. Three Pianists. During the last month, we were preoccupied with composers and completely ignored the performers, who bring their music to the public. So today we bring you three wonderful pianists: Radu Lupu, a Romanian, Mitsuko Uchida, born in Japan, and András Schiff, a British-Hungarian. All three belong to the same generation: Lupu was born in 1945 (on November 30th), Uchida in 1948 (on December 20th), and Schiff – in 1953, on December 21st. Uchida and Schiff are still performing, Lupu died on April 17th of last year.

Radu Lupu is widely considered one of the greatest pianists of his time. He studied in Moscow with Heinrich Neuhaus, who also taught Richter and Gilels. In the three years from 1966 to 1969, he won three major piano competitions, the Cliburn, the Enescu, and the Leeds, and embarked on an international career with successful concerts in London. Though he played all major composers of the 18th and 19th centuries, he was most closely associated with the music of Schubert, Schumann and Brahms. Here is Schubert’s Impromptu in A flat major, D. 935, no. 2 from a legendary 1982 Decca recording of Schubert’s Impromptus D. 899 and D.935.

Lupu probably didn’t need any competition wins for his tremendous talent to be noticed by the public and the critics. Mitsuko Uchida didn’t need them either: all she got from competing in the majors was second place in the 1975 Leeds (a solid Dmitry Alekseyev won, and Schiff shared the third prize). Uchida’s family moved to Vienna when she was 12. She studied there at the Academy of Music (Wilhelm Kempff was one of her teachers). In the 1980s Uchida moved to London and has lived there since. In 2009, she was made Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire, the second-highest British award. Uchida is rightfully famous for her Mozart, but her repertoire is very broad, from Haydn to Schoenberg. Here’s Mozart’s Piano Sonata No. 12 in F major, K.332, and here – one of the 12 Etudes by Debussy, no. 3, Pour les Quartes.

András Schiff fared even worse than Uchida in international competitions: in addition to third prize at the Leeds which we mentioned above, all he got was a shared fourth prize at the 1974 Tchaikovsky competition (the 18-year-old Andrei Gavrilov was the winner; a talented pianist, he had an interesting but brief career, which in its significance could not be compared to Schiff’s). András Schiff was born into a Jewish family in Budapest. He studied at the Franz Liszt Academy of Music there (György Kurtág was one of his professors and Zoltán Kocsis, who studied there at the same time, became a friend). He also took summer classes with Tatiana Nikolayeva and Bella Davidovich. Since the late 1980s he, like Uchida, has been living in London, and like her, was knighted (in 2014). Schiff is one of the most admired pianists of his generation; he feels comfortable in many venues: he plays recitals and concertos, loves ensemble playing, and often accompanies singers. His Bach is wonderful, but so are his Mozart and Haydn, Schubert and Schumann. He often played the music of his fellow Hungarian Bela Bartók but is very critical of the current political situation in his country of birth and even said that he’ll never set foot there. Here’s András Schiff playing Bach’s French Suite no. 4, recorded in 1991. This recording was made in Reitstadel, a former animal feed storage barn built in the 14th century and in our time converted into a concert hall. It’s located in the Bavarian town of Neumarkt in der Oberpfalz. Read more...

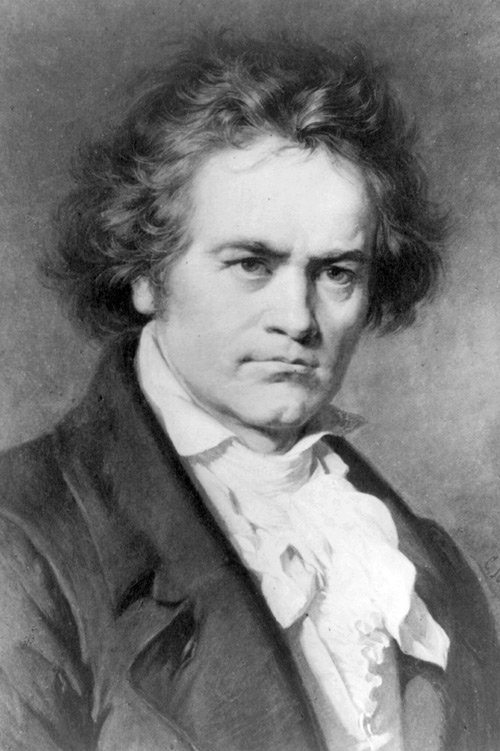

This Week in Classical Music: December 11, 2023. Beethoven and Berlioz. On December 16th we’ll celebrate Ludwig van Beethoven’s 253rd anniversary. As we thought of it, we remembered what happened on this date three years ago when the world was supposed to celebrate a monumental date, Beethoven’s 250th. It didn’t happen, as our musical organizations couldn’t bring themselves to honor a white male composer – that was the year of Critical Race Theory run amok, DEI ruling the world, and sanity running for cover On the website Music Theory’s White Racial Frace, Philip Ewell, a black musicologist, published an article titled “Beethoven Was an Above Average Composer – Let’s Leave It at That” which contained a sentence: “But Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is no more a masterwork than Esperanza Spalding’s 12 Little Spells.” Alex Ross, our most important public music critic, felt compelled to respond to this nonsense with an article of his own, publishing “Black Scholars Confront White Supremacy in Classical Music” in the New Yorker magazine. The article's subtitle was: “The field must acknowledge a history of systemic racism while also giving new weight to Black composers, musicians, and listeners.” In the New York Times, Anthony Tomassini, the chief classical music critic who is no longer with the newspaper, wrote an article about the harm of the blind, behind-the-curtain orchestral auditions. Those were widely accepted a quarter century ago to avoid any racial or gender biases, but Tomassini argued that it hinders the racial diversification of our orchestras: “The audition process should take into account race, gender and other factors.” We wonder if he still thinks that way, or was that just intellectual cowardice, an attempt to cover his hide: after all, for decades he was toiling in a field that purportedly turned out to be racist through and through, and in all these years it never occurred to him to assess it in racial terms. All of this was just three years ago. This major burst of insanity seems to be behind us and hopefully will dissipate completely, sooner rather than later. Do we need to add a disclaimer that we are totally against any racial and gender discrimination, whether in music or any other cultural or social sphere? We hope not.

Back to Beethoven. We looked up our library, and it turns out that while we have most of Beethoven’s piano sonatas, we don’t have the sonata no. 19, a short and misnumbered piece, easy enough to be well known to practically all young pianists. Beethoven composed it sometime in 1797, about the same time as his sonatas nos. 3 and 4, but it wasn’t published till 1805 and thus acquired its late opus and number. Here it is, performed by Alfred Brendel in a 1992 recording.

Also, on this day 220 years ago Hector Berlioz was born in La Côte-Saint-André, a small town halfway between Lyon and Grenoble. Berlioz was one of the greatest composers France ever produced, and a very unusual one at that: he didn’t follow any established schools and didn’t leave any behind. We’ve written about Berlioz many times, and he requires a separate entry, so for now, here is his symphony cum viola concerto Harold in Italy (parts 1, Harold in the mountains,2, March of the pilgrims, 3, Serenade of an Abruzzo mountaineer, and 4, Orgy of bandits). The great violinist Yehudi Menuhin is playing the viola, with Sir Colin Davis conducting the Philharmonia Orchestra.Read more...

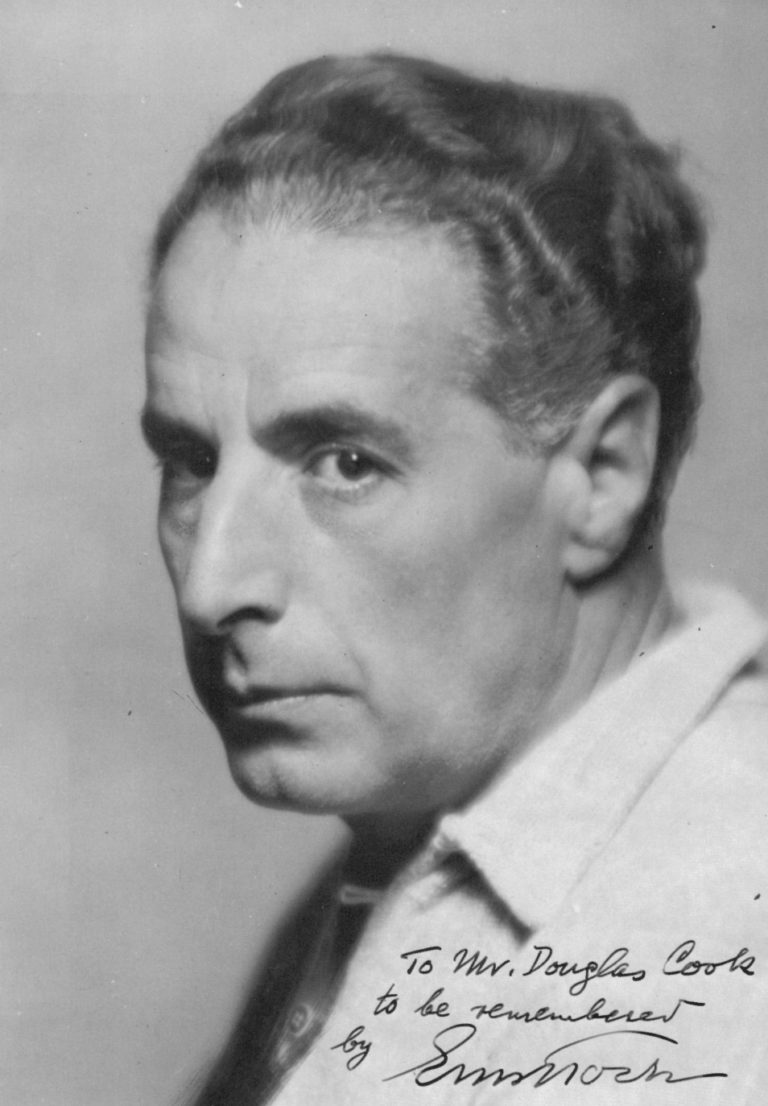

This Week in Classical Music: December 4, 2023.Ernst Toch and more.Erns Toch, the Jewish-Austrian composer, was born on December 7th of 1887 in Leopoldstadt, a poor, mostly Jewish area in Vienna.Toch was one of a group of Austrian and German composers whose lives were upended by the rise of Nazism (Arnold Schoenberg, Franz Schreker, Karl Weigl, Egon Wellesz, Hans Gál, Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Berthold Goldschmidt, all Jewish, mostly forgotten except of course for Schoenberg, all talented if to a different degree, had their lives broken in 1933).One thing we find interesting is the ease with which they moved from Austria to Germany.These were two very different empires, one, declining, ruled by the peace-seeking Emperor Franz Joseph from Vienna, another – very much on the ascent, economically, politically and militarily, ruled by the arrogant and insecure Keiser Wilhelm II.But musicians thought nothing of moving from one country to another, from Vienna to Berlin and back, conducting in Hamburg or Leipzig one year and then returning to Austria, teaching at Berlin’s Hochschule für Musik and then at Universität für Musik in Vienna.And they didn’t need permission to work as long as positions were available.Musically, the pre-WWI Austria and Germany were one space, even more so than they are now.

Toch was at his most productive in the 1920s, when he wrote the Concerto for Cello and Chamber Orchestra, Bunte Suite, two short operas, many chamber pieces and piano music.Here’s Bunte Suite, whose sophisticated humor reminds us of the music of another Austrian composer, Ernst Krenek.The Suite is performed by the Karajan Academy of the Berliner Philharmoniker, Cornelius Meister conducting.You can read about Toch’s life after Hitler assumed power in last year’s post.

Jean Sibelius was also born this week, on December 8th of 1865.We have to admit that we’re not big fans of the Finnish composer, but his one-movement Symphony no. 7, is a masterpiece.Even though it’s his shortest, about 23 minutes long depending on performance, it took Sibelius 10 years (from 1914 to 1924) to complete.During that time, he managed to complete two more symphonies, nos. 5 and 6.Here’s the Seventh, performed by the Berlin Philharmonic under the direction of Herbert von Karajan.

While Sibelius may not be one of our favorites, Olivier Messiaen, born on December 10th of 1908, clearly is.We’ve written about him on several occasions and will get back to the great French master soon.Also this week: Henryk Górecki, a Polish composer whose minimalist symphonies became very popular with audiences worldwide, born on December 6th of 1933, and César Franck, the composer of one of the best violin sonatas, on December 10th of 1822.Read more...

This Week in Classical Music: November 27, 2023.Maria Callas.We’re a bit early, but next Sunday is the 100th anniversary of Maria Callas, La Divina, as she was known worldwide: she was born on December 2nd of 1923.It feels very strange that’s already been a century since her birth, as her presence is felt as strongly today as on the day she died in 1977: her instantly recognizable voice could be heard on classical music radio stations, on streaming services, on YouTube and (still) on CDs.The means have changed – back then it was LPs that people were buying and listening to – but she’s as adored as ever.Her Casta Diva alone has been heard on YouTube about 35 million times.Callas was so closely associated with Italian opera – Bellini, Donizetti, Verdi, Puccini – that she seemed Italian, but in fact was American, of Greek descent.She married an Italian, Giovanni Battista Meneghini, and, while they were married used his name with her own as Maria Meneghini Callas.She moved to Greece in 1940 and studied voice at the Athen Conservatory.There, she sang in the opera for the first time, appearing as Tosca in 1942.She returned to the US in 1945 but soon left for Italy.Tulio Serafin, the famous conductor who coached generations of singers, became her mentor.In 1947, at the Arena of Verona, he conducted Callas in her first Italian role, as La Gioconda in Ponchielli’s eponymous opera.Her appearance was tremendously successful and brought her career to a different level.During that time she often sang in the rarely produced bel canto operas, mostly because she was the only one who could sing these very difficult roles.She was exceptional as Donizetti’s Anna Boleyn, as Imogene and Norma in Bellini’s Il Pirata and Norma, Lucia in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, Lady Macbeth and Violetta in Verdi's Macbeth and Traviata, and, of course, as Tosca.For three years she sang in smaller theaters, then, in 1950, she appeared, as Aida in La Scala.Even though her relationship with the management was troubled, in the 1950s La Scala became Callas’s home.Neither did Callas have a rapport with Rudolph Bing, the manager of the Met, where she premiered only in 1956.She had a reputation as a temperamental diva, but many of her colleagues thought that it was her exactness that made her difficult to work with.Later in the 1950s, she started experiencing problems with her voice, which may have contributed to her sometimes-erratic behavior.Some think that it was the loss of weight that affected her voice; in the early 1950s Callas was rather heavy, but then went on a diet and lost about 80 pounds.By the late 1950s, her vibrato was too heavy, sometimes the voice was forced and one could hear pronounced harshness, even though other performances were still excellent.Overall, Callas sang at the top of her form for just 10 years but what glorious years they were!Even her detractors, and there are some, recognize that the interpretations of the roles she sang were incomparable, it’s her voice that some people have problems with.We think that at its peak her voice was uniquely beautiful, and she created exceptional operatic characters that in other interpretations seem dull.Even the often mediocre music (and Italian operas are full of it) sounded exciting when she sang.There are none even close to La Divina on the opera stage today, and we don’t expect to hear anybody of that rank anytime soon.Read more...

This Week in Classical Music: November 20, 2023.The Spaniards and a bit of Genealogy.Three Spanish composers were born this week: Manuel de Falla, on November 23rd of 1876, Francisco Tárrega, on November 21st of 1852, and Joaquin Rodrigo, on November 21st of 1901.Falla is probably the most important of the three – some might say the most important Spanish composer of the 20th century – although Tárrega was also instrumental in advancing Spanish classical music, which prior to the arrival of Tárrega and his friends Albéniz and Granados had been stagnant for many decades, practically since the death of Padre Antonio Soler in 1783.(It’s interesting to note that the Spanish missed out almost completely on symphonic music).Falla’s most interesting works were composed for the stage: the drama La Vida Breve, ballets El Amor Brujo and Three-Cornered Hat, the zarzuela (a Spanish genre that incorporates arias, songs, spoken word, and dance) Los Amores de la Inés.A fine pianist, he also composed many pieces for the piano, Andalusian Fantasy among them.Tárrega’s preferred instrument was the guitar: he was a virtuoso player, and he also composed mostly for the instrument.(Tárrega had a unique guitar with a very big sound, made by one Antonio Torres, a famous luthier).Here’s one of his best-known pieces, Recuerdos de la Alhambra (Memories of the Alhambra), performed by Sharon Isbin.

Rodrigo also wrote mostly for the guitar: his most famous piece is Concierto de Aranjuez, from 1939, for the guitar and orchestra.Here’s the concerto’s first movement; John Williams is the soloist; Daniel Barenboim leads the English Chamber Orchestra.The recording is almost fifty years old, from 1974, but still sounds very good.

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, Johann Sebastian’s eldest son and a wonderful composer in his own right, was born on November 22nd of 1710.Here’s our entry about Wilhelm Friedemann from some years ago. We sympathize with Friedemann: he was brooding, mostly unhappy, and quite unlucky, but he wrote music that we find superior to that of his much more famous brother, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach.And here’s an interesting historical tidbit: one of Wilhelm Friedemann’s harpsichord pupils was young Sara Itzig, daughter of Daniel Itzig, a Jewish banker of Frederick II the Great of Prussia.Daniel, one of the few Jews with full Prussian citizenship, had 13 children; Sara was born in 1761.She was a brilliant keyboardist and commissioned and premiered several pieces by Wilhelm Friedeman and CPE Bach.Sara married Salomon Levy in 1783 and had an important salon in Berlin.One of her sisters, Bella Itzig, married Levin Jakob Salomon; they had a son, Jakob Salomon, who upon converting to Christianity, took the name Bartholdy.His daughter Lea married Abraham Mendelssohn, son of the famous Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn.Lea and Abraham had two children, Felix and Fanny Mendelssohn; their full name was Mendelssohn Bartholdy.Sara had a big influence on the musical education of her grandnephew Felix.Bella gave a manuscript of Johann Sebastian Bach’s St Matthew Passion to her grandson in 1824; Felix conducted the first 19th-century revival of the Passion in 1829.So, there’s a line, quite convoluted but fascinating, going from the Bach family to Felix (and Fanny) Mendelssohn.The Itzigs were a remarkable family: in addition to all the connections above, two other sisters, Fanny and Cecilie Itzig, were patrons of Mozart.Maybe we’ll get to that someday.Read more...

This Week in Classical Music: November 13, 2023.Transitioning.Not in the sense of Classical Connect’s gender identity, but as a state of mind, which being in Rome largely is.CC is back in the US, but already missing Rome.

Papa Mozart (Leopold) was born this week, in 1719.He was a minor composer and music teacher but is remembered as the father of his genius son, whose career he managed (or exploited, as some would say) for many years.

Johann Nepomuk Hummel was born on November 14th of 1778 in Pressburg (now Bratislava).When he was eight, the family moved to Vienna.Like Mozart, he was a child prodigy: according to his father, he could read music at the age of four, and at the age of five he could play the piano and the violin very well.In 1786, Hummel was offered music lessons by none other than Mozart, who also housed him for two years, all free of charge.Even though Mozart was 22 years older than the boy, they played billiards and spent time together.At the age of nine Hummel performed one of Mozart’s piano concertos.Very much like Leopold Mozart, Hummel’s father took his child on a European tour.They ended up in London and stayed there for four years, Hummel taking lessons from Muzio Clementi.In 1791, Haydn, who knew the young Hummel from his visits to Mozart’s house in Vienna, was also staying in London; he dedicated a piano sonata to the boy, who performed it in public to great success.The French Revolution, the Terror and the subsequent wars changed the Hummels’s plans, and in 1793 they returned to Vienna.There Hummel continued taking music lessons, with Antonio Salieri and Joseph Haydn.One of Haydn’s pupils was Beethoven; the young men became friends.Hummel played at Beethoven’s memorial concert in 1827, and there he met Franz Schubert, who later dedicated his last three piano sonatas (some of the greatest piano music ever written) to Hummel.

In 1804 Hummel succeeded Haydn as the Kapellmeister to Nikolaus II, Prince Esterházy in Eisenstadt.He stayed there for seven years, returning to Vienna in 1811.After successfully touring Europe with his singer-wife and working in Stuttgart, Hummel settled in Weimar, being offered the position of the Kapellmeister at the Grand Duke’s court.He arrived there in 1819 and stayed for the rest of his life (Hummel died in 1837), making numerous touring trips in the meantime.He became friends with Goethe and turned the city into a major music center.At the court theater, he staged and conducted new operas by Weber, Rossini, Auber, Meyerbeer, Halévy, and Bellini.He also established one of the first pension plans for retired musicians, sometimes playing benefit concerts to replenish the funds.In 1832, Goethe died, Hummel’s health was failing, and he semi-retired, formally retaining his position of the Kapellmeister.Hummel died five years later.

During his lifetime, Hummel was one of the most celebrated pianists in the world and a very popular composer.He was also an important cultural figure, a music entrepreneur, and a famous, sought-after, and very expensive piano teacher.As a composer, he was a transitional figure between the Classical style and Romanticism.Even though he heavily influenced many composers of his time, Chopin and Schumann among them, nowadays Hummel’s music is mostly forgotten.He wrote operas, sacred music, many orchestral pieces, concertos, chamber music, and of course numerous piano pieces.Very little of it is still performed.Here’s Hummel’s Piano Sonata no. 4, Op.38.It’s played by the Korean pianist Hae-Won Chang.Read more...

This Week in Classical Music: November 6, 2023.Rome, II.Classical Connect is still in Rome.On Saturday we went to a Santa Cecilia concert with Antonio Pappano conducting the Accademia's Orchestra and Igor Levit playing Beethoven's Third Piano Concerto.But we'd like to start with a decidedly non-musical detail.The Santa Cecilia Hall, inaugurated in 2002, was designed by the famous Italian architect, Renzo Piano.Many of Piano's pieces are airy and light, but not this one.It has little ambiance, despite the use of wood, and looks uninviting.The seating, which follows that of the Berliner Philharmonie, is placed all around the orchestra in shallow layers. We're not sure about the acoustics of the hall, as this was our first visit and we've never heard the Accademia Orchestra live, so it's not clear if the numerous imbalances (shrill winds, for example) are the orchestra's fault or the hall's.

But the most fascinating part of the hall's design is the men's bathroom.It has no urinals, only cabins.Men stand in line, not sure which cabin is empty, and enter one that's just vacated.When things get tough, they go around knocking on doors.The question is, were the urinals eliminated as a gesture of support for some feminist causes, or was Signor Piano not aware of how most men's toilets are usually (and efficiently) constructed?

But let’s get back to music.The program consisted of Cherubini’sAnacréon overture, Beethoven's Third PianoConcerto, Sibelius’s En Saga, and Richard Strauss’sTill Eulenspiegel.

Pappano’s entrance was accompanied by thunderous applause.The wind’s first entrance in the Cherubini was not a happy event.Things got better as they moved along, but even though Beethoven rated Cherubini highly, it’s little surprise that his music is played rarely these days.

Beethoven's Third Piano Concerto was a very different story.Igor Levit was superb.His technique seems to have improved since the last time we heard him in Chicago, and his command of the piece was total, even if one may disagree with some of his tempi.The performance was greeted ecstatically, and he played, exquisitely, an encore, Brahms’s Intermezzo in A major, Op. 118.

After the intermission, Pappano presented Sibelius with a speech and made the audience sing a tune from what was to follow.That was much more entertaining than the En Saga itself.The choice of the final piece, TillEulenspiegel, would seem rather unusual, as the winds are not this orchestra's strong suit, but it went well, better than one might have expected judging by the three previous pieces.

If you add a hair-raising ride in a Roman taxi to the concert and back, this was, overall, quite an exhilarating event.Read more...

This Week in Classical Music: October 30, 2023.Rome, I.Classical Connect is in Rome this week, so this entry is short.Rome overwhelms visually: the sites, interiors of churches worthy of museums, and Roman museums, some of the best in the world. And of course, the magical Roman light. Aurally, things are very different: the usual cacophony of crowds and the ever-jammed traffic, the sirens of the police cars and ambulances trying to get through, and awful street musicians, strategically positioned where the largest crowds congregate but also wandering the streets, assailing the dining public with their renditions of the European schlagers of the 1980s.

Historically, Rome has always been one of the greatest musical centers of Europe, and there are dozens of places, from the Vatican to the palaces of the cardinals and nobility, that are linked to major musical events of the past, but sometimes these connections take a different shape, quite literally: the enormous Borghese palace, which is still the major residence of the family (part of the palazzo is occupied by the Spanish embassy) is nicknamed Il Cembalo, and its plan does look like a harpsichord, with the narrowest side facing the Tiber.

In the next couple of days, Antonio Pappano will be conducting the orchestra of the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in a program of Cherubini, Beethoven (Piano Concerto no. 3 with Igor Levit), Sibelius and Strauss’s Till Eulenspiegel.The site classictic.com, which sells tickets online, decided that the composer of the last piece is Johann Strauss.

This Week in Classical Music: October 23, 2023.Short notes, II.Today is Ned Rorem’s 100th anniversary.Rorem died last year, just days short of his 99th birthday.He was a wonderful composer of songs and a whimsical writer.He spent almost a decade in France, where for a while he studied with Arthur Honegger (rather than Nadia Boulanger, as many American composers and pianists had done).In 1966 he published a book, Paris Diaries, based on his real diaries, full of gossip, gay stories, and a good read overall.In addition to about 500 art songs, some exceptionally good, he wrote two full-length operas, one of which, Our Town, based on a play by Thornton Wilder, was successfully staged in the US and abroad (he also wrote several smaller, one-act operas).In addition to that he composed three symphonies and a lot of piano music, including two concertos, but none of that music was as successful as his songs.Here is Rorem’s Sonnet.Susan Graham is accompanied by the pianist Malcolm Martineau and Ensemble Oriol.

If Rorem wrote about 500 art songs, Domenico Scarlatti, who was born on October 26th of 1685, wrote more than 500 piano sonatas.They are mostly short, about as long as Rorem’s songs.Domenico was born in Naples, where his father, the renowned opera composer Alessandro Scarlatti, was working as maestro di capella at the court of the Spanish Viceroy of Naples.Though a thoroughly Italian composer, his link with Spain lasted throughout his life.He moved to Spain in 1729 and lived there for the remaining 25 years of his life.

Another Italian, Luciano Berio, was also born this week, on October 24th of 1925.He was one of the most influential composers of the 20th century.You can read more about him here.

Niccolo Paganini and Georges Bizet both had their anniversaries this week, as did a minor but talented Russian composer of liturgical music, Alexander Gretchaninov.Next year is his 160th anniversary, so we’ll dedicate a post to him.Read more...

This Week in Classical Music: October 16, 2023.Short notes.It could’ve been a pretty good week, considering the talent we could celebrate, but the horrendous events of October 7th and their aftermath overwhelmed everything else.So, we’ll go over our list very briefly.The Italian composer Luca Marenzio was born onOctober 18th, 1553 (or 1554) in Coccaglio, near Brescia.Marenzio was one of the most prolific (and famous) composers of madrigals of the second half of the 16th century. Marenzio was lucky in finding great benefactors. For many years he had served at the court of Cardinal Luigi d’Este, son of Ercole II d'Este, Duke of Modena and Ferrara.After the cardinal’s death, Marenzio found employment with Cardinal Cinzio Aldobrandini, nephew of Pope Clement VIII, and later, with Ferdinando I de' Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany.We can assume that while in Florence, he met the three Florentine composers whose lives we had followed closely in our recent posts – Giulio Caccini, Jacopo Peri, and Emilio de' Cavalieri, but while he inhabited the same intellectual circles as the three, Marenzio never got interested in their ideas about monody and opera.He did, nevertheless, write music for two out of six intermedi to the play La Pellegrina, composed for the wedding of the Grand Duke Ferdinando to Christina of Lorraine in 1589 (Cavalieri oversaw the production and composed one of the intermedi, Caccini composed another one, Peri was both composer and a singer).That same year Marenzio returned to Rome and went on an adventurous trip to Poland, to the court of King Sigismund III Vasa in Warsaw.He stayed in Poland for a year, got seriously ill there, and returned to Rome, where he died in 1599.

Franz Liszt was also born this week, on October 22nd of 1811 in a small Hungarian village next to the border with Austria. One interesting snippet about Liszt that we were not aware of till recently: he didn’t speak Hungarian.Two fine Soviet pianists, Emil Gilels and Yakov Flier, both excellent interpreters of Liszt’s music, also have their anniversaries this week: Gilels was born on October 19th, 1916 in Odesa, Flier – on October 21st, 1912 – in a small town of Orekhovo-Zuyevo not far from Moscow.

Baldassare Galuppi and Georg Solti were also born this week, but as with so much else, we’ll leave them for better days.Read more...

This Week in Classical Music: October 8, 2023.Verdi, War.Today is the 210th anniversary of Giuseppe Verdi’s birth, but we’re not in the mood to celebrate it: it seems inappropriate with the war raging in Israel and Gaza after the Hamas barbaric terrorist attack.There are many trite sayings about the power of music to heal, to make peace, but they all seem shallow in comparison to the news of civilians being killed in cold blood or the horror of the Israeli kids being abducted by Hamas into Gaza.If anything, throughout history music has been used to make war, from military bands leading troops into battle to Nazis using it in concentration camps.(And no, the Ride of the Valkyries wasn’t used in Vietnam by the US helicopter pilots, it was Francis Ford Coppola’s brilliant invention).

We thought of maybe using parts of Verdi’s Requiem or the famous chorus of the Hebrew Slaves, Va', pensiero (Fly, my thoughts), from his opera Nabucco, but that didn’t feel right either. So we’ll leave it at that.

Two great pianists were also born this week, Evgeny Kissin, who’ll turn 52 tomorrow, and Gary Graffman, who will celebrate his 95th birthday on the 14th of October.Both are Jewish; Kissin was born in Russia (then the Soviet Union), Graffman’s parents came from Russia.Hamas, if they could, would like to kill all Jews, no matter where they live.And they would definitely not spare musicians.Read more...

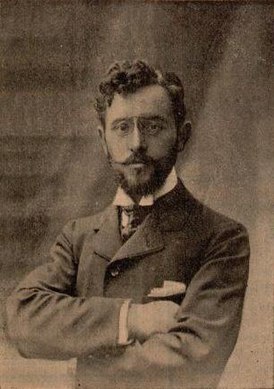

This Week in Classical Music: October 2, 2023.Giulio Caccini.During the last couple of months, we’ve published several entries ontwo subjects: one, the musical transition from the Renaissance to the Baroque and early opera, and another, about some unsavory but talented characters in music.The protagonist of today’s entry falls into both categories.Giulio Caccini was born in Rome on October 8th, 1551.One episode that puts him into the “unsavory” category happened in 1576 when Caccini was in Florence employed by the court of Grand Duke Francesco I de’ Medici.Francesco had a brother, Pietro, who was married to the beautiful Eleonora (Leonora) di Garzia di Toledo.Pietro was known to be gloomy and violent, the marriage was unhappy, and Leonora had several affairs.Caccini, attempting to curry favors from the Duke’s family, spied on Leonora and then denounced her and her lover, Bernardino Antinori, to Pietro.Pietro brought Leonora to Villa Medici at Cafaggiolo, where he strangled her with a dog leash.Leonora was 23.Bernardino Antinori was imprisoned and also killed.The whole story is even more sordid and involves other characters and victims, but though fascinating, it goes even further into Italian history and away from music.One note: if the name of Antinori sounds familiar to wine lovers, it’s not by chance – Bernardino’s family has been making wines since 1385.These days Antinori produce some of the best Chiantis and Super-Tuscans in Italy.

Other episodes are not as gruesome but still attest to Caccini’s character.Two more talented composers worked at the court at the same time, Emilio de' Cavalieri and Jacopo Peri.In 1600, the wedding of Henry IV of France and Maria de' Medici was a very important event.Cavalieri, who oversaw all major festivities of the house of Medici, was expected to direct this one as well.The conniving Caccini had him denied the position, and while Cavalieri did write some of the music, it was Caccini who managed the staging (we described this event here).The disappointed Cavalieri left Florence never to return.As for Peri, the stories are more comical.Upon learning that Peri was writing an opera, Euridice, for the wedding of Maria de' Medici to Henry IV, he rushed to compose his own version using the same libretto and had it published before the first performance of Peri’s work.That wasn’t all; Caccini’s daughter Francesca, a talented singer, was to participate in the performance of Peri’s Euridice.Even though Peri wrote the music for the whole opera, Caccini rewrote the parts performed by Francesca and several other singers under his command, all that just to spite Peri and promote himself.Francesca Caccini, by the way, turned into an excellent composer in her own right.Her opera, La liberazione di Ruggiero dall’isola d’Alcina (The Liberation of Ruggiero from the Island of Alcina) was just staged by the Chicago Haymarket Opera Company (yesterday was the last performance).

Even though Caccini wrote three operas, he’s better remembered for his collection of songs called Le nuove musiche (the New Music), published in 1602.Here are two songs from this collection, Amor, io parte and Alme luci beate, but the whole collection is wonderful.In this 1983 recording, the soprano is Montserrat Figueras, the wife of Jordi Savall, who accompanies her on the Viola da Gamba (Figueras died in 2011).Hopkinson Smith is playing the lute.Read more...

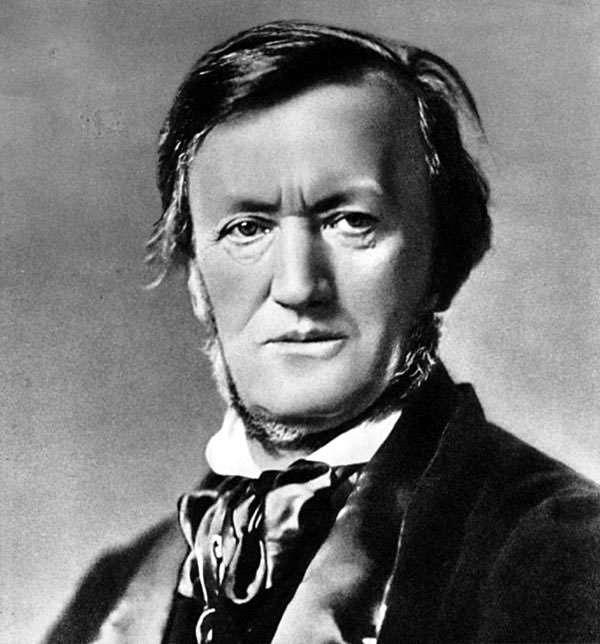

This Week in Classical Music: September 25, 2023.Florent Schmitt. We have to admit that we’re fascinated with the “bad boys” of music.They are invariably “boys,” as there are no “bad girls” in music historiography that we’re aware of.As for the male composers, there are plenty, Richard Wagner being the quintessential one.In the last couple of years, we’ve written about several of them, mostly the Germans in the 20th century, even though they are not the only ones: there were plenty of baddies in the Soviet bloc and, in a very different way, several Italians of the Renaissance.This week it’s Florent Schmitt’s turn, a French composer infamous for shouting “Vive Hitler!” during a concert.(Dmitri Shostakovich was also born this week, and, as talented as he was, he was no angel either, but we’ll return to Shostakovich another time).Schmitt was born on September 28th of 1870 in the town of Meurthe-et-Moselle, Lorraine, the area that was passing from France to Germany and back for centuries – thus the German name.At 17, he entered the conservatory in nearby Nancy, and two years later moved to Paris where he studied composition with Gabriel Fauré and Jules Massenet.While in Paris, Schmitt became friends with Frederick Delius, the English composer of German descent who was then living in Paris.In the 1890s he befriended Ravel and met Debussy.

Schmitt tried to get the prestigious Prix de Rome five times, submitting five different compositions every year from 1896 to 1900, when he finally won it with the cantata Sémiramis.He spent three years in Rome and then traveled extensively, visiting Russia and North Africa, among other places.One of his most popular pieces composed during the period after Rome is the Piano Quintet op. 51 (1902-1908).Schmitt dedicated it to Fauré.Here’s the final movement, Animé, performed by the Stanislas Quartet with Christian Ivaldi at the piano.The ballet La tragédie de Salomé was composed during the same period, in 1907.Igor Stravinsky was taken by it; in Grove’s quote, he wrote to Schmitt: “I am only playing French music – yours, Debussy, Ravel’.And later, “I confess that [Salomé] has given me greater joy than any work I have heard in a long time.”In 1910 Schmitt created a concert version of the ballet.Here’s the second part of it (the New Philharmonia Orchestra is conducted by Antonio de Almeida).It’s not surprising that Stravinsky liked it, as it clearly presages parts of Rite of Spring.Another important piece, Psalm XLVII, was written in 1906.

During WWI Schmitt wrote music for military bands but returned to regular composing once the war was over.He also worked as a music critic for the newspaper Le Temps.Schmitt was a nationalist with pronounced sympathies toward the Nazi regime.The episode we referred to at the beginning of this entry happened in November of 1933.During a concert of the music of Kurt Weill, a Jewish composer who had beenrecently forced into exile by the Nazis, he stood up and shouted “Vive Hitler!”According to a witness, he added: “We already have enough bad musicians to have to welcome German Jews.”That makes him not only a Nazi sympathizer but also an antisemite.During the German occupation of France, Schmitt collaborated with the Vichy government and was a member of the Music section of the France-Germany Committee. He visited Germany and in December of 1941 went to Vienna to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Mozart’s death.After the liberation, Schmitt was investigated as a collaborator, but these proceedings were later dropped, although a year-long ban was imposed on performing and publishing his music.Soon after everything was forgotten and in 1952, just seven years after the end of the war, Schmitt was made the Commander of the Legion of Honor.In 1996, the controversial past of this "one of the most fascinating of France's lesser-known classical composers," as he’s often described, came into prominence again, and his name was removed from a school and a concert hall.Read more...

This Week in Classical Music: September 18, 2023.Several conductors. We missed a lot of anniversaries while exploring the music of the transitional period between the Renaissance and early Baroque.Today we’ll get back to a group of conductors.First, Karl Böhm, one of the most successful of them.Böhm was born on August 28th of 1894 in Graz, Austria.His career took off in the 1920s, with some help from Bruno Walter; in 1927 Böhm was appointed the chief musical director in Darmstadt, and in 1931 he took the same position at the prestigious Hamburg Opera.In 1933 the Nazis came to power in Germany and Böhm took over the Dresden Semper Opera, after Fritz Busch, the previous director, went into exile.Böhm was a friend of Richard Strauss and conducted several premiers of his operas.In 1938 Böhm appeared at the Salzburg Festival, and in 1943 took over the famous Vienna opera.For many years Böhm was a Nazi sympathizer, though never a member of the NSDAP; after the war, he went through a two-year denazification period, and then his career took off again.He continued his engagements with Vienna and Dresden, conducted in South America, and made a very successful New York debut in 1957.He frequently led the Metropolitan, premiering operas by Berg and Strauss and successfully conducting many of Wagner’s operas (Birgit Nilsson debuted under Böhm’s baton).Böhm’s final engagements were in London, at Covent Garden and with the London Symphony.He died on August 14th of 1981, two weeks shy of his 87th birthday.

Here is Richard Strauss’s Ein Heldenleben (A Hero's Life), a tone poem from 1898.Karl Böhm conducts the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra.This recording was made in 1976.Also, quite recently we came across a DW documentary from 2022 called Music in Nazi Germany: The Maestro and the Cellist of Auschwitz (here).It’s very much worth watching.The maestro in question is not Karl Böhm but Wilhelm Furtwängler, eight years older than Böhm and more established.Still, much of what is said in the documentary about Furtwängler applies to Böhm (we think that to an even higher degree).A note: the “kapellmeister” of the Auschwitz women’s orchestra, Alma Rosé, mentioned in the documentary, died there in April of 1944.Alma was the daughter of Arnold Rosé, the concertmaster of the Vienna Philharmonic for 50 years and the leader of the famous Rosé Quartet.Alma’s mother was Gustav Mahler’s sister.

We mentioned Bruno Walter’s name above; he also happens to be one of the conductors we wanted to write about.Walter was born on September 15th of 1876 in Berlin.We celebrated him several years ago here.At least as talented as Böhm, his life couldn’t have been more different.Walter was Jewish, for many years he collaborated closely with Mahler and, in 1912, led the posthumous premier performance of the composer’s Ninth Symphony.He was the music director of the Bavarian State Opera in Munich, where he conducted most of Wagner’s operas.Walter escaped from Germany in 1933 (at the time he was the principal conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra).After working in Europe, he moved to the US in 1939 and settled in Beverly Hills, the area that hosted a large German expat community.In the US, he worked with many orchestras, including the Chicago Symphony, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and the Philadelphia Orchestra.Bruno Walter was 85 when he died in 1962.Here Bruno Walter is playing the piano and conducting the NBC Symphony Orchestra in Mozart’s Piano Concerto no. 20.This is a live recording made on November 3rd of 1939.

Just to list other conductors in our group: István Kertész (b. August 28, 1929); three conductors, born on September 1: Tullio Serafin (in 1878), Leonard Slatkin (in 1944), Seiji Ozawa, (in 1935).Christoph von Dohnányi was born on September 8, 1929, and Christopher Hogwood, on September 10, 1941.Read more...