Années de Pèlerinage, Deuxième Année: Italie - 2014

Années de Pèlerinage, Deuxième Année: Italie - 2014

November 3, 2014.Années de Pèlerinage, Deuxième Année: Italie.Even though today is the birthday of Vincenzo Bellini (he was born in 1801 in Catania, Sicily, and we’ve written about him extensively in the past, here and here), we’ll continue the traversal of Franz Liszt’s Années de Pèlerinage.This time it’s the second year of the pilgrimage, and we’re in Italy.As always, we’ll illustrate every piece with performances by pianists young and renowned: the Canadian Jason Cutmore plays Sposalizio and Canzonetta del Salvator Rosa, the great Alfred Brendel plays Penseroso, Lazar Berman plays the first two of the three Sonetto del Petrarca, Sonetto.47 and Sonetto 104, and the legendary Russian pianist Vladimir Sofronitsky – Sonetto 123, in a 1952 recording.Finally, the young Swiss pianist Beatrice Berrut plays what Liszt called “Fantasia Quasi Sonata” Après une Lecture de Dante.Here’s the article by Joseph DuBose.

The second volume of Années de Pèlerinage is a catalogue of Liszt’s travels through Italy. Unlike its predecessor, however, it does convey depictions of Italy’s landscapes and cities, but instead impressions of its rich artistic heritage. As Liszt traveled the Italian Peninsula, he traversed its centuries of artistic excellence, from the immortal writings of Dante and Petrarch, to the paintings of Raphael, the sculptures of Michelangelo, and even the music of Bononcini, whose death preceded Liszt’s travels by roughly only a century. Like the preceding volume, the pieces of Deuxième Année are revisions of those Liszt originally composed during the time of his pilgrimage, some quite extensively and amounting, in essence, to full-fledged rewritings, such as with the three Petrarch sonnets. The volume was published 1858, three years after the first.

Deuxième Année opens with Liszt’s musical portrayal of Raphael’s The Marriage of the Virgin in “Sposalizio” (here). The innocence and reverence of the subject matter is displayed in the simple pentatonic melody of the opening measures, stated without any further adornment, and answered by an expectant motif tucked within the inner tones of contrasting chords. Repeated incessantly, the pentatonic theme drives the first section of the piece, through wide-ranging harmonies, to a fortissimo conclusion in E major. A brief passage, combining the fragments of the theme with the answering motif, then leads the listener into the piece’s second main theme. A pious wedding march in G major, this new theme, given in a rich, chordal texture, is accompanied by the pentatonic theme. At first, its appearance is only occasional. However, following a modulation back into the tonic key of E major and the recommencement of the wedding march, the pentatonic theme becomes a permanent fixture of the accompaniment. Against the wedding march, it creates a glistening accompaniment of almost Impressionistic colors, and an continuous flow of energy that climaxes in the expectant motif of the beginning. From thence, the music recedes, with the pentatonic theme still heard above echoes of the wedding march, into the final, quiet tonic chords. (Continue).

Starkly different from the opening piece is “Il Penseroso” (here), which took its inspiration from two creations of the Renaissance polymath, Michelangelo. The first was a statue that sits atop the tomb of Lorenzo de’ Medici in Florence; the second, was a quatrain from a poem, and reveals the reason for the pensive tone of Liszt’s musical reflection: “Sweet is my sleep, but more to be mere stone, / So long as ruin and dishonour reign; / To bear nought, to feel nought, is my great gain; / Then wake me not, speak in an undertone!” An ominous dotted-eight rhythm dominates the music, under which heavily chromatic harmonies move about. The melodic line reaches across a lengthy expanse (in terms of time), moving very little, but instead remaining fixated on a single tone and driven more by changes in harmony. The melody is partially repeated, where it is given a varied, but no less austere, utterance with full-voice chords atop a chromatically moving bass line. From its peak, it recedes into a passage of ninth chords that ultimately pull the music back into the tonic key of C-sharp minor. Against alternating tonic chords and Neapolitan sixths, the ominous dotted-eighth rhythm draws the piece towards in close.

Dispelling the dark mood of “Il Penseroso” is the jolly, march-like “Canzonetta del Salvator Rosa” (here), a rather late addition to the suite as it was composed in 1849, well after Liszt had returned from Italy. Salvator Rosa’s poem begins thusly: “While I’ll often change my place of means, the fire of my love remains unchanged.” It is likely that more than these mere words were the source of inspiration behind Liszt’s setting. Besides being a painter and poet of the Baroque era, Rosa’s artistry in some ways foreshadowed the later Romantics, and his reputation as “unorthodox” and a “perpetual rebel” likely found a sympathetic reaction in Liszt. The melody itself was believed to have been composed by Rosa as well, but is actually the creation of another Italian—Giovanni Bononcini. Liszt’s arrangement is rather straightforward, with the words of Salvator Rosa even printed above the melody. Holding the canzonetta’s three strains together is the melody’s head motif, which is often used in imitation.

The following three pieces form a triptych inspired by the Renaissance poet Petrarch, and are heavily revised versions of previous compositions by Liszt. The originals were composed in 1838-39 for piano and tenor, near the end of his sojourn with Marie d’Agoult. In 1846, around the time the songs first appeared in print, Liszt revisited them, crafting the first piano arrangements. These, however, would undergo let another process of revision in 1858 when he decided to include them in the second volume of Années de Pèlerinage. Of the three versions, these are undoubtedly the best, combining a maturity of technique to Liszt’s ebullient, youthful expression of love. Incidentally, the songs themselves would be revised in 1868, when Liszt produced a greatly altered version for lower voice.

The first of the Petrarchan sonnets is “Benedetto sia ‘l giorno” (“Blessed be the day”), in which the poet praises the day that Laura first bestowed a glance upon him (here). Pierced to his heart and overcome by her beauty, all his thoughts and writing from then on dwell forever upon her. That crucial and life-altering moment for Petrarch can be heard in the introductory measures of Liszt’s setting, after which the syncopated melody sings out with earnest devotion and affection. The anguished longing, however, of the poet is expressed in the second sonnet, “Pace non trovo” (“I find no peace”), here. Imprisoned by love and caught in the midst of a fog of contradictions—neither existing, nor perishing; weeping, but laughing; hating himself, but loving another—he realizes the source of all his torments: Laura. Liszt’s music, likewise, wavers between moments of anguish and affection, many times within the same phrase. A frantic pitch is maintained by the near constant forte dynamic throughout much of the piece. However, in the final bars, when the poet names his lady as the source of both suffering and elation, the music slowly settles into a resigned piano. Lastly, The final sonnet compares the beauty of Laura to that of the angels and heaven (here). Her eyes outshine the sun; her words move mountains and stay rivers; and the lament of her tears, filled with love and wisdom, is such a sweet sound on earth that heaven dares not to shake a single leaf. The transcendental state of Petrarch’s poem is achieved in the lengthy introduction to Liszt’s setting, which begins so poignantly with a diminished seventh harmony moving into a dominant eleventh, resulting in a long, sustained dissonance that does not find its ultimate resolution until the final bars before the entrance of the melody. From its initial presentation, Liszt’s rendering of the melody expresses every detail of Petrarch’s sonnet. At the close of its first statement, the dreams and shadows cast upon the poet’s memory are brought out in the momentarily unsettled harmony before the music settles into minor as the he witnesses Laura’s tears at the opening of the second stanza. A stillness then begins to come upon the music in the final measures. The melody, no longer as animated as before, rings out clearly over the reappearance of the introductory chords. Harp-like arpeggios, separated by faint “sighs”, alternate between the tonic of A-flat and E major during the last measures, creating a truly ethereal scene, and brings the first six pieces of Deuxième année to a heavenly close.

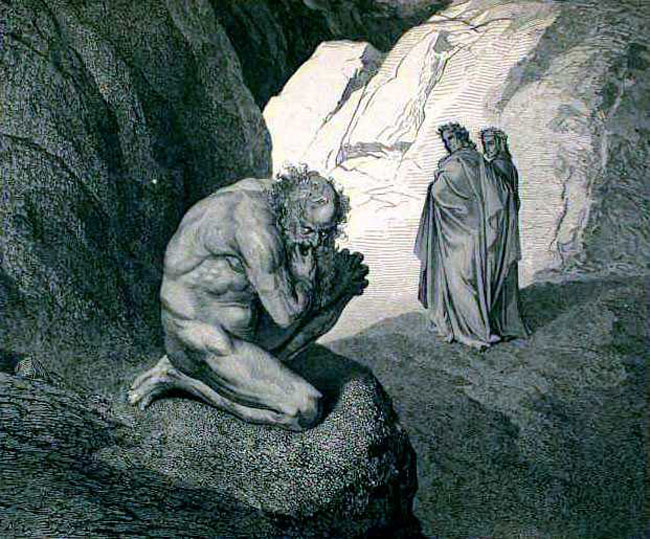

Occupying roughly a third of the total length of the second volume, Après une Lecture du Dante (also referred to as the “Dante Sonata”), here, draws its inspiration from the most famous of Dante Aleghieri’s poems: the Divine Comedy. Like the theme of Faust, Dante’s depiction of Hell was of particular interest to Liszt, who revisited it once again in his Dante Symphony. Originally conceived as a smaller piece in the 1830s, the Sonata, like the other pieces of Années de pèlerinage, underwent significant revision and expansion while Liszt resided in Weimar. The resultant piece is quite appropriately subtitled by Liszt as “Fantasia quasi Sonata.” Approaching the dimensions of the sonata, and borrowing elements to help maintain its structural unity, the piece yet remains, in essence, a fantasia—quite the opposite from Beethoven’s famous “Moonlight” Sonata which reads, “Sonata quasi Fantasia.” Surpassing the lengthy Vallée de Obermann of the first volume, Après une Lecture du Dante is the largest-scale solo piano work Liszt would compose before the Sonata in B minor.

The Sonata makes prominent use of the tritone interval, once commonly referred to as “diabolus in musica,” or “the Devil in music.” The initial D minor tonality of the sonata, interestingly a key with connotations of death, forms the interval with the A-flat major of the previous piece. Most noticeably, however, it opens with a chain of descending tritones, sounded forte in bare octaves and with a fanfare-like rhythm. It culminates in a poignant semitone motif that creates a biting dissonance against the cadential harmonic figure occurring above. From the passage of tritones emerges an agitated, chromatic figure that represents the approach of the tormented souls in Hell. To great effect, Liszt purposely blurs the contours of melody and harmony with an indication for the sustain pedal to be held for a full five measures. Following the chromatic theme, and a brief reappearance of the fanfare rhythms, a new idea appears—a choral-like subject in F-sharp major, played triple-forte, which one of Liszt’s pupils described as a portrait of Lucifer himself.

After another statement of the chromatic theme, given in a more restrained triplet rhythm, the third theme proper is presented. Deriving itself from the previous F-sharp major chorale, the theme is most aptly described by the following passage from the Divine Comedy: “For there is no greater pain, than to remember in present grief, past happiness.” Another interpretation is the presence of Beatrice, who appearance several times in Dante’s depiction of Hell. Regardless, fragments of the chromatic theme are interwoven within the musical texture against the yearning second theme, and ultimate leads to its poignant return accompanied by rippling arpeggios. From thence, the initial themes of the piece are worked out in a freely conceived development, beginning with a reappearance of the opening tritone fanfares. The chorale subject, however, does not return until close to the conclusion, where it resurfaces in the key of D major, thus marking the Sonata’s “recapitulation.” Intertwined within this restatement are both the tritone fanfares and the chromatic theme. The chromatic theme makes a final appearance in a rousing section that leads into a series of fanfares over a bass descending through a whole-tone scale. Triple-forte fanfares reaffirm the key of D major, and the piece closes with a fitting plagal cadence.

Années de Pèlerinage, Deuxième Année: Italie - 2014

November 3, 2014. Années de Pèlerinage, Deuxième Année: Italie. Even though today is the birthday of Vincenzo Bellini (he was born in 1801 in Catania, Sicily, and we’ve written about him extensively in the past, here and here), we’ll continue the traversal of Franz Liszt’s Années de Pèlerinage. This time it’s the second year of the pilgrimage, and we’re in Italy. As always, we’ll illustrate every piece with performances by pianists young and renowned: the Canadian Jason Cutmore plays Sposalizio and Canzonetta del Salvator Rosa, the great Alfred Brendel plays Penseroso, Lazar Berman plays the first two of the three Sonetto del Petrarca, Sonetto.47 and Sonetto 104, and the legendary Russian pianist Vladimir Sofronitsky – Sonetto 123, in a 1952 recording. Finally, the young Swiss pianist Beatrice Berrut plays what Liszt called “Fantasia Quasi Sonata” Après une Lecture de Dante. Here’s the article by Joseph DuBose.

Deuxième Année opens with Liszt’s musical portrayal of Raphael’s The Marriage of the Virgin in “Sposalizio” (here). The innocence and reverence of the subject matter is displayed in the simple pentatonic melody of the opening measures, stated without any further adornment, and answered by an expectant motif tucked within the inner tones of contrasting chords. Repeated incessantly, the pentatonic theme drives the first section of the piece, through wide-ranging harmonies, to a fortissimo conclusion in E major. A brief passage, combining the fragments of the theme with the answering motif, then leads the listener into the piece’s second main theme. A pious wedding march in G major, this new theme, given in a rich, chordal texture, is accompanied by the pentatonic theme. At first, its appearance is only occasional. However, following a modulation back into the tonic key of E major and the recommencement of the wedding march, the pentatonic theme becomes a permanent fixture of the accompaniment. Against the wedding march, it creates a glistening accompaniment of almost Impressionistic colors, and an continuous flow of energy that climaxes in the expectant motif of the beginning. From thence, the music recedes, with the pentatonic theme still heard above echoes of the wedding march, into the final, quiet tonic chords. (Continue).

Starkly different from the opening piece is “Il Penseroso” (here), which took its inspiration from two creations of the Renaissance polymath, Michelangelo. The first was a statue that sits atop the tomb of Lorenzo de’ Medici in Florence; the second, was a quatrain from a poem, and reveals the reason for the pensive tone of Liszt’s musical reflection: “Sweet is my sleep, but more to be mere stone, / So long as ruin and dishonour reign; / To bear nought, to feel nought, is my great gain; / Then wake me not, speak in an undertone!” An ominous dotted-eight rhythm dominates the music, under which heavily chromatic harmonies move about. The melodic line reaches across a lengthy expanse (in terms of time), moving very little, but instead remaining fixated on a single tone and driven more by changes in harmony. The melody is partially repeated, where it is given a varied, but no less austere, utterance with full-voice chords atop a chromatically moving bass line. From its peak, it recedes into a passage of ninth chords that ultimately pull the music back into the tonic key of C-sharp minor. Against alternating tonic chords and Neapolitan sixths, the ominous dotted-eighth rhythm draws the piece towards in close.

a statue that sits atop the tomb of Lorenzo de’ Medici in Florence; the second, was a quatrain from a poem, and reveals the reason for the pensive tone of Liszt’s musical reflection: “Sweet is my sleep, but more to be mere stone, / So long as ruin and dishonour reign; / To bear nought, to feel nought, is my great gain; / Then wake me not, speak in an undertone!” An ominous dotted-eight rhythm dominates the music, under which heavily chromatic harmonies move about. The melodic line reaches across a lengthy expanse (in terms of time), moving very little, but instead remaining fixated on a single tone and driven more by changes in harmony. The melody is partially repeated, where it is given a varied, but no less austere, utterance with full-voice chords atop a chromatically moving bass line. From its peak, it recedes into a passage of ninth chords that ultimately pull the music back into the tonic key of C-sharp minor. Against alternating tonic chords and Neapolitan sixths, the ominous dotted-eighth rhythm draws the piece towards in close.

Dispelling the dark mood of “Il Penseroso” is the jolly, march-like “Canzonetta del Salvator Rosa” (here ), a rather late addition to the suite as it was composed in 1849, well after Liszt had returned from Italy. Salvator Rosa’s poem begins thusly: “While I’ll often change my place of means, the fire of my love remains unchanged.” It is likely that more than these mere words were the source of inspiration behind Liszt’s setting. Besides being a painter and poet of the Baroque era, Rosa’s artistry in some ways foreshadowed the later Romantics, and his reputation as “unorthodox” and a “perpetual rebel” likely found a sympathetic reaction in Liszt. The melody itself was believed to have been composed by Rosa as well, but is actually the creation of another Italian—Giovanni Bononcini. Liszt’s arrangement is rather straightforward, with the words of Salvator Rosa even printed above the melody. Holding the canzonetta’s three strains together is the melody’s head motif, which is often used in imitation.

The following three pieces form a triptych inspired by the Renaissance poet Petrarch, and are heavily revised versions of previous compositions by Liszt. The originals were composed in 1838-39 for piano and tenor, near the end of his sojourn with Marie d’Agoult. In 1846, around the time the songs first appeared in print, Liszt revisited them, crafting the first piano arrangements. These, however, would undergo let another process of revision in 1858 when he decided to include them in the second volume of Années de Pèlerinage. Of the three versions, these are undoubtedly the best, combining a maturity of technique to Liszt’s ebullient, youthful expression of love. Incidentally, the songs themselves would be revised in 1868, when Liszt produced a greatly altered version for lower voice.

Occupying roughly a third of the total length of the second volume, Après une Lecture du Dante (also referred to as the “Dante Sonata”), here, draws its inspiration from the most famous of Dante Aleghieri’s poems: the Divine Comedy. Like the theme of Faust, Dante’s depiction of Hell was of particular interest to Liszt, who revisited it once again in his Dante Symphony. Originally conceived as a smaller piece in the 1830s, the Sonata, like the other pieces of Années de pèlerinage, underwent significant revision and expansion while Liszt resided in Weimar. The resultant piece is quite appropriately subtitled by Liszt as “Fantasia quasi Sonata.” Approaching the dimensions of the sonata, and borrowing elements to help maintain its structural unity, the piece yet remains, in essence, a fantasia—quite the opposite from Beethoven’s famous “Moonlight” Sonata which reads, “Sonata quasi Fantasia.” Surpassing the lengthy Vallée de Obermann of the first volume, Après une Lecture du Dante is the largest-scale solo piano work Liszt would compose before the Sonata in B minor.

Sonata, like the other pieces of Années de pèlerinage, underwent significant revision and expansion while Liszt resided in Weimar. The resultant piece is quite appropriately subtitled by Liszt as “Fantasia quasi Sonata.” Approaching the dimensions of the sonata, and borrowing elements to help maintain its structural unity, the piece yet remains, in essence, a fantasia—quite the opposite from Beethoven’s famous “Moonlight” Sonata which reads, “Sonata quasi Fantasia.” Surpassing the lengthy Vallée de Obermann of the first volume, Après une Lecture du Dante is the largest-scale solo piano work Liszt would compose before the Sonata in B minor.

The Sonata makes prominent use of the tritone interval, once commonly referred to as “diabolus in musica,” or “the Devil in music.” The initial D minor tonality of the sonata, interestingly a key with connotations of death, forms the interval with the A-flat major of the previous piece. Most noticeably, however, it opens with a chain of descending tritones, sounded forte in bare octaves and with a fanfare-like rhythm. It culminates in a poignant semitone motif that creates a biting dissonance against the cadential harmonic figure occurring above. From the passage of tritones emerges an agitated, chromatic figure that represents the approach of the tormented souls in Hell. To great effect, Liszt purposely blurs the contours of melody and harmony with an indication for the sustain pedal to be held for a full five measures. Following the chromatic theme, and a brief reappearance of the fanfare rhythms, a new idea appears—a choral-like subject in F-sharp major, played triple-forte, which one of Liszt’s pupils described as a portrait of Lucifer himself.

After another statement of the chromatic theme, given in a more restrained triplet rhythm, the third theme proper is presented. Deriving itself from the previous F-sharp major chorale, the theme is most aptly described by the following passage from the Divine Comedy: “For there is no greater pain, than to remember in present grief, past happiness.” Another interpretation is the presence of Beatrice, who appearance several times in Dante’s depiction of Hell. Regardless, fragments of the chromatic theme are interwoven within the musical texture against the yearning second theme, and ultimate leads to its poignant return accompanied by rippling arpeggios. From thence, the initial themes of the piece are worked out in a freely conceived development, beginning with a reappearance of the opening tritone fanfares. The chorale subject, however, does not return until close to the conclusion, where it resurfaces in the key of D major, thus marking the Sonata’s “recapitulation.” Intertwined within this restatement are both the tritone fanfares and the chromatic theme. The chromatic theme makes a final appearance in a rousing section that leads into a series of fanfares over a bass descending through a whole-tone scale. Triple-forte fanfares reaffirm the key of D major, and the piece closes with a fitting plagal cadence.