Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

June 24, 2013. Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli. Yet again we’re celebrating composers whose birthdays remain unknown to music historians, but who were very important to the development of the Western musical tradition. Andrea Gabrieli, a Venetian, was born around 1532. If that’s the case (some other sources place his birth earlier, in the 1520s), he was seven years younger than Palestrina and about the same age as Orlando di Lasso. At the time, Franco-Flemish composers were the leading creative force in Italy, and there’s some evidence that Andrea took lessons from one of them, Adrian Willaert, who is considered the founder of the Venetian School of music. From Willaert he learned how to write polyphonic music. He spent some time in Verona and then returned to Venice and settled in Cannaregio, the northern district of the city (the area where the first Jewish Ghetto was created at the beginning of the century). Around 1555 he competed, unsuccessfully, for the position of an organist at the San Marco. In 1562 he traveled to Germany and while in Munich met Orlando di Lasso. Both men benefited from this relationship, exchanging ideas and learning from each other. In 1564 Gabrieli returned to Venice and in 1566 received the coveted position of an organist at the San Marco cathedral (as the second organistuntil 1584, when he was promoted to the position of the first organist). His duties at San Marco included composing, and not just the church music but also music for official ceremonies. For example, he wrote music for the celebrations of the historic victory of the Venetian fleet over the Ottoman Turks at Lepanto in 1571. Later in his life Andrea became a teacher. His most famous pupil was his own nephew, Giovanni. Here is Andrea Gabrieli’s Magnificat for three choirs; it’s performed by ensemble Chanticleer.

At the time, Franco-Flemish composers were the leading creative force in Italy, and there’s some evidence that Andrea took lessons from one of them, Adrian Willaert, who is considered the founder of the Venetian School of music. From Willaert he learned how to write polyphonic music. He spent some time in Verona and then returned to Venice and settled in Cannaregio, the northern district of the city (the area where the first Jewish Ghetto was created at the beginning of the century). Around 1555 he competed, unsuccessfully, for the position of an organist at the San Marco. In 1562 he traveled to Germany and while in Munich met Orlando di Lasso. Both men benefited from this relationship, exchanging ideas and learning from each other. In 1564 Gabrieli returned to Venice and in 1566 received the coveted position of an organist at the San Marco cathedral (as the second organistuntil 1584, when he was promoted to the position of the first organist). His duties at San Marco included composing, and not just the church music but also music for official ceremonies. For example, he wrote music for the celebrations of the historic victory of the Venetian fleet over the Ottoman Turks at Lepanto in 1571. Later in his life Andrea became a teacher. His most famous pupil was his own nephew, Giovanni. Here is Andrea Gabrieli’s Magnificat for three choirs; it’s performed by ensemble Chanticleer.

Giovanni, the more famous of the Gabrielis, was also born in Venice sometime between 1554 and 1557. As a youth he studied with his uncle, whom he revered and who was a father figure for Giovanni. Later, between 1575 and 1579, also following in the steps of his uncle, he went to Germany to study with Orlando di Lasso in Munich. He returned to Venice in 1584 and succeeded Andrea as the second organist at the San Marco. Soon after he became the principal organist at the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, one of the most influential confraternities in Venice (today it’s mostly famous for its magnificent frescoes by Tintoretto, who was still working on them at the time of Gabrieli’s employ). Like his uncle, Giovanni also became an important teacher: one of his pupils was Heinrich Schütz, who became a major early Baroque composer, probably the most significant German composer before Johann Sebastian Bach. Giovanni composed a large number of purely instrumental music (for example, his Sacrae symphoniae) and a large number of choral motets. His fame spread all over Italy, on par with Palestrina’s; one ruled the music world of Rome, the other – in Venice. Gabrieli, who in his last years was often sick and could not perform his duties at the Cathedral, died on April 12, 1612, in Venice. We’ll hear Giovanni Gabrieli’s In Ecclesiis. It was written in a typical Venetian ”polychoral” manner, that is to be performed by several choirs. It was also written specifically for the Cathedral of San Marco: each choir was to occupy a separate position in this magnificent church. It is performed (here) by the Choir of King's College and Philip Jones Brass Ensemble.Permalink

father figure for Giovanni. Later, between 1575 and 1579, also following in the steps of his uncle, he went to Germany to study with Orlando di Lasso in Munich. He returned to Venice in 1584 and succeeded Andrea as the second organist at the San Marco. Soon after he became the principal organist at the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, one of the most influential confraternities in Venice (today it’s mostly famous for its magnificent frescoes by Tintoretto, who was still working on them at the time of Gabrieli’s employ). Like his uncle, Giovanni also became an important teacher: one of his pupils was Heinrich Schütz, who became a major early Baroque composer, probably the most significant German composer before Johann Sebastian Bach. Giovanni composed a large number of purely instrumental music (for example, his Sacrae symphoniae) and a large number of choral motets. His fame spread all over Italy, on par with Palestrina’s; one ruled the music world of Rome, the other – in Venice. Gabrieli, who in his last years was often sick and could not perform his duties at the Cathedral, died on April 12, 1612, in Venice. We’ll hear Giovanni Gabrieli’s In Ecclesiis. It was written in a typical Venetian ”polychoral” manner, that is to be performed by several choirs. It was also written specifically for the Cathedral of San Marco: each choir was to occupy a separate position in this magnificent church. It is performed (here) by the Choir of King's College and Philip Jones Brass Ensemble.Permalink

June 17, 2013. Stravinsky and the Rite of Spring. Igor Stravinsky was born on this day in 1882, but just a couple weeks ago we passed another significant milestone: the one hundredth anniversary of the premier of Le Sacre du printemps, or The Rite of Spring, his seminal achivement. The event took place in Paris on May 29, 1913 in the newly opened Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. The ballet was performed by Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes company; it was choreographed by Vaslav Nijinsky; Nikolai Roerich created the costumes and stage design. Stravinsky, then 31 years old, was already successful and quite famous. Three years earlier he wrote music for his first ballet, The Firebird, also for Ballets Russe (Diagilev, the impresario, first approached more established composers, Liadov and Tcherepnin, but eventually gave the commission to Stravinsky). The Firebird was a triumph, a breakthrough both for Stravinsky and Diagilev, who immediately asked the composer to collaborate with him on another project. Stravinsky proposed The Great Sacrifice, a ballet he was discussing with Nikolai Roerich, which would eventually become The Rite of Spring; and Diagilev agreed. Stravinsky started working on it the same year, 1910, but soon switched to a different project; Diagilev, with his keen ear, decided that it’s worth staging, and soon Petrushka was born. If anything, it was even more successful than The Firebird: the immensely talented Vaslav Nijinsky danced the title role, created for him by Mikhail Fokine, and the celebrated painter Alexandre Benois designed the sets. Soon after the premier Stravinsky returned to The Rite. He was living in Clarens, a village on the shores of Lake Geneva, working in a small

May 29, 1913 in the newly opened Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. The ballet was performed by Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes company; it was choreographed by Vaslav Nijinsky; Nikolai Roerich created the costumes and stage design. Stravinsky, then 31 years old, was already successful and quite famous. Three years earlier he wrote music for his first ballet, The Firebird, also for Ballets Russe (Diagilev, the impresario, first approached more established composers, Liadov and Tcherepnin, but eventually gave the commission to Stravinsky). The Firebird was a triumph, a breakthrough both for Stravinsky and Diagilev, who immediately asked the composer to collaborate with him on another project. Stravinsky proposed The Great Sacrifice, a ballet he was discussing with Nikolai Roerich, which would eventually become The Rite of Spring; and Diagilev agreed. Stravinsky started working on it the same year, 1910, but soon switched to a different project; Diagilev, with his keen ear, decided that it’s worth staging, and soon Petrushka was born. If anything, it was even more successful than The Firebird: the immensely talented Vaslav Nijinsky danced the title role, created for him by Mikhail Fokine, and the celebrated painter Alexandre Benois designed the sets. Soon after the premier Stravinsky returned to The Rite. He was living in Clarens, a village on the shores of Lake Geneva, working in a small room with a piano and practically no furniture. He completed the first half (The Adoration of the Earth) in the summer of 1912, and even prepared a version for four hands, which he performed with Claude Debussy in Paris. The second half (The Sacrifice) and the orchestration were finished in March of 1912. He showed the score to Maurice Ravel, who thought it a very important piece of music. Pierre Monteux, then the conductor of the Ballets Russes and not a big fan of the score, suggested some changes that Stravinsky accepted.

room with a piano and practically no furniture. He completed the first half (The Adoration of the Earth) in the summer of 1912, and even prepared a version for four hands, which he performed with Claude Debussy in Paris. The second half (The Sacrifice) and the orchestration were finished in March of 1912. He showed the score to Maurice Ravel, who thought it a very important piece of music. Pierre Monteux, then the conductor of the Ballets Russes and not a big fan of the score, suggested some changes that Stravinsky accepted.

The premier turned into a major scandal. Protests started almost from the beginning, even before the curtain rose to reveal the stamping dancers, and it went downhill from there. Witnesses said that the audience was screaming so loudly that it was almost impossible to hear the music. Stravinsky soon left the hall and watched the rest of the performance from the wings. Both the music and Nijinsky’s choreography were offensive to many in the audience. With passions heating up, a fight broke out in the hall. Eventually people’s ire turned to the orchestra and all kinds of things flew into the pit; the stoic Monteux continued conducting without interruptions (several arrests were made after the performance). The public settled down somewhat during the second half; there were even curtain calls at the end. Some critics thought the music “barbarous,” and it’s said that Camille Saint-Saëns left the theater in disgust; Puccini called the music “cacophony.” This didn’t stop Diagilev from taking the troupe to London, were the response was not as hostile. Critical opinion, however, changed rather quickly. These days The Rite is acknowledged as one of the most influential pieces of music of the 20th century, a masterpiece that influenced generations of composers. It’s also one of the most often recorded compositions. We’ll hear it in the performance by the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, Michael Tilson Thomas conducting.

PermalinkJune 10, 2013. Thomas Tallis. Even though the ever-popular Edvard Grieg, who wrote many wonderful tunes and became the first national composer of the newly independent Norway, was born this week on June 15, 1843, we’ll write about him some other time. Today we’ll remember a composer whose date of birth, together with much of the details of his life, were lost in centuries past: Thomas Tallis. What we do know is that he was born early in the 16th century (1505 is the commonly assumed year). We also know that he worked as on organist in the Dover priory around 1530, and later at the Canterbury Cathedral. Around 1543 he became a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal, a group of clerics and musicians who traveled with the British monarchs in order to serve their spiritual needs. In this capacity he played and composed for four kings and queens from Henry VIII to Elizabeth I. In 1575 Tallis, who was then 70, and the composer William Byrd, half his age at the time, were given a monopoly to publish music and music paper. Their first publication, Cantiones Sacrae, was a set of 34 motets, 16 by Tallis and 18 by Byrd, and it was the only music published during Tallis’s lifetime.

Today we’ll remember a composer whose date of birth, together with much of the details of his life, were lost in centuries past: Thomas Tallis. What we do know is that he was born early in the 16th century (1505 is the commonly assumed year). We also know that he worked as on organist in the Dover priory around 1530, and later at the Canterbury Cathedral. Around 1543 he became a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal, a group of clerics and musicians who traveled with the British monarchs in order to serve their spiritual needs. In this capacity he played and composed for four kings and queens from Henry VIII to Elizabeth I. In 1575 Tallis, who was then 70, and the composer William Byrd, half his age at the time, were given a monopoly to publish music and music paper. Their first publication, Cantiones Sacrae, was a set of 34 motets, 16 by Tallis and 18 by Byrd, and it was the only music published during Tallis’s lifetime.

Tallis lived till the age of 80, and during his life England was transformed from a Catholic country with a Latin liturgy to an Anglican one, with a liturgy in English. He wrote both, and his output is divided between Latin and English pieces. Among his Latin works, the setting of The lamentations of Jeremiah were widely praised then and still remain one of his most celebrated compositions. You can listen to it here, in the performance of the ensemble Magnificat directed by Philip Cave. Another hauntingly beautiful example is his setting of Miserere Nostri. It’s performed (here) by the eponymous ensemble, The Tallis Scholars. And here is an example of his "English" music, a set of nine simple but beautiful psalms called "Tunes for Archbishop Parker's Psalter," performed by the British ensemble Stile Antico. The Tunes were written in 1567 for Matthew Parker, the first Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury. The English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams used the third Tune, Why Fum'th In Fight (it’s the first one to be performed in this recording), for his Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis. The Tunes are still included in many Anglican hymnals.

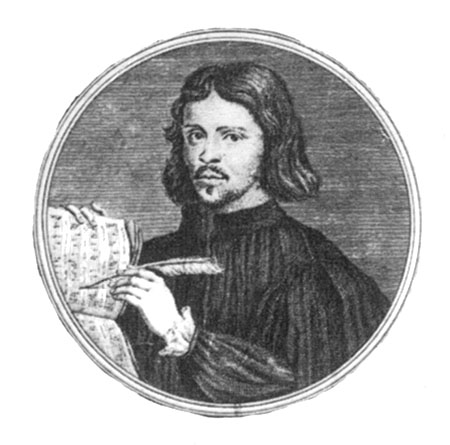

Two notes: the portrait above was made by Gerard Vandergucht, a British engraver of Flemish descent, about 150 year after Tallis’s death, so there’s no certainty that he actually looked anything like it. There were no portraits of Tallis made during his life, so we have to contend with this one. Another note: apparently, Tallis’s music, a motet called Spem in Alium (here) is mentioned in the enormously popular soft-core novel Fifty Shades of Grey. As a result, since the publication of the novel the sales of Tallis’s album with this motet exploded, reaching number one on the UK classical music charts. Whatever it is that brings the listeners to his music, Tallis would’ve been pleased.

PermalinkJune 3, 2013. Robert Schumann and more. One of the greatest Romantic composers, Robert Schumann was born on June 8, 1810 in Zwickau, Saxony. Schumann is central to modern music, especially the piano repertory, and we wrote about him and featured his music many times (our library contains more than 200 recordings of his music). Schumann was also highly creative as a critic, and practically invented the genre of “programmatic” music. All of his early compositions were for the piano, but he started writing for other instruments later in his career. Schumann turned out to be an extraordinary songwriter, second probably only to Schubert. He composed the cycle Dichterliebe (The Poet's Love) in 1840. It consists of 16 songs, the texts to which come from Heinrich Heine’s Lyrisches Intermezzo. The cycle was dedicated to the great German soprano Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient, so we know that Schumann intended it for a female voice. The music was too good to be passed up by the male singers though, and is performed by them at least as often. The great German baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau recorded Dichterliebe several times, among his collaborators were Vladimir Horowitz and Alfred Brendel. So did the French baritone Gérard Souzay (we recently heard him exquisitely singing an aria from Lully’s Cadmus et Hermione). The tenors Peter Schreier and, closer to our times, Ian Bostridge made memorable recordings as well. The famed Lotte Lehmann recorded the cycle with the conductor Bruno Walter at the piano in 1940; several years later Walter accompany Kathleen Ferrier in yet another recording. One of the very best, at least in our opinion, is the recording made by the great German tenor Fritz Wunderlich. Accompanied by Hubert Giesen, Wunderlich made this recording in October and November of 1965 and July 1966, just two months before his untimely death at the age of 36. It was too difficult to select "favorite" sections, so here it is, in its entirely.

Schumann was also highly creative as a critic, and practically invented the genre of “programmatic” music. All of his early compositions were for the piano, but he started writing for other instruments later in his career. Schumann turned out to be an extraordinary songwriter, second probably only to Schubert. He composed the cycle Dichterliebe (The Poet's Love) in 1840. It consists of 16 songs, the texts to which come from Heinrich Heine’s Lyrisches Intermezzo. The cycle was dedicated to the great German soprano Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient, so we know that Schumann intended it for a female voice. The music was too good to be passed up by the male singers though, and is performed by them at least as often. The great German baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau recorded Dichterliebe several times, among his collaborators were Vladimir Horowitz and Alfred Brendel. So did the French baritone Gérard Souzay (we recently heard him exquisitely singing an aria from Lully’s Cadmus et Hermione). The tenors Peter Schreier and, closer to our times, Ian Bostridge made memorable recordings as well. The famed Lotte Lehmann recorded the cycle with the conductor Bruno Walter at the piano in 1940; several years later Walter accompany Kathleen Ferrier in yet another recording. One of the very best, at least in our opinion, is the recording made by the great German tenor Fritz Wunderlich. Accompanied by Hubert Giesen, Wunderlich made this recording in October and November of 1965 and July 1966, just two months before his untimely death at the age of 36. It was too difficult to select "favorite" sections, so here it is, in its entirely.

Several other composers were born around this date, and we’ll write more about them at a later date, but here are two of them: the peripatetic Scott, Georg Muffat was born on June 1, 1653 in Savoy. Here is his Sonata No. 2 in G minor from the set known as Armonico Tributo. Composed in Rome, Armonico was clearly influenced by Arcangelo Corelli, whom Muffat met while staying in the city. The Sonata is performed by Ensemble 415, Chiara Banchini conducting. A century and a half later, also on June 1 but of 1804, Mikhail Glinka, "the father of Russian classical music," was born. Like Muffat, he was influenced by the Italians, but had enough of his own original talent to produce operas that are staged even today, and not just in Russia. Here is his Overture to the 1842 opera Ruslan and Lyudmila. The recording was made by Evgeny Mravinsky and his famed Leningrad Philharmonic in concert in 1965. It’s probably the speediest rendition of the Overture in the recording history, but the strings manage to play (practically) every note.Permalink

May 27, 2013. Albéniz and Korngold. Isaac Albéniz, the oldest of the three composers who put Spanish music back on the music map (the other two being Granados and de Falla), was born on May 29, 1860 in a small town of Camprodon in northern Catalonia. He was a piano prodigy and started performing at the age of four. Legend has it that he ran away from home twice before reaching the age of 13, each time supporting himself by playing public concert. At the age of seven he passed the piano entrance exams at the Paris Conservatory but wasn’t admitted because of his age. At 14 he briefly went to the Leipzig conservatory and when money run out, to Brussels’s Royal Conservatory where he received a grant. In 1883 he returned to Spain to teach in Madrid and Barcelona. Albéniz was composing from an early age but took the craft seriously only after meeting Felipe Pedrell, a teacher and composer, around the time he returned to Spain. Three years later, in 1886, he composed Suite española for piano. The suite consists of eight pieces, each dedicated to different regions of Spain (the last one is called Cuba, then a Spanish colony). In 1893 Albéniz moved to Paris, where he befriended Vincent d’Indy, Paul Dukas, and other composers. Between 1905 and 1909 he wrote Iberia, a set of four “books,” each containing three pieces. Iberia became his most famous and popular composition. (The wonderful Spanish pianist Alicia de Larrocha was one of the best interpreters of Albéniz’s music. Here she is playing Book 1 of Iberia: Evocación, El puerto and Fête-dieu à Seville). By that time Albéniz was very sick with a kidney disease. He died on May 18, 1909, age 48, in Cambo-les-Bains, a French Basque town on the border of Spain.

northern Catalonia. He was a piano prodigy and started performing at the age of four. Legend has it that he ran away from home twice before reaching the age of 13, each time supporting himself by playing public concert. At the age of seven he passed the piano entrance exams at the Paris Conservatory but wasn’t admitted because of his age. At 14 he briefly went to the Leipzig conservatory and when money run out, to Brussels’s Royal Conservatory where he received a grant. In 1883 he returned to Spain to teach in Madrid and Barcelona. Albéniz was composing from an early age but took the craft seriously only after meeting Felipe Pedrell, a teacher and composer, around the time he returned to Spain. Three years later, in 1886, he composed Suite española for piano. The suite consists of eight pieces, each dedicated to different regions of Spain (the last one is called Cuba, then a Spanish colony). In 1893 Albéniz moved to Paris, where he befriended Vincent d’Indy, Paul Dukas, and other composers. Between 1905 and 1909 he wrote Iberia, a set of four “books,” each containing three pieces. Iberia became his most famous and popular composition. (The wonderful Spanish pianist Alicia de Larrocha was one of the best interpreters of Albéniz’s music. Here she is playing Book 1 of Iberia: Evocación, El puerto and Fête-dieu à Seville). By that time Albéniz was very sick with a kidney disease. He died on May 18, 1909, age 48, in Cambo-les-Bains, a French Basque town on the border of Spain.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold was born on May 29, 1897 in Brno, the capital of Moravia in the Czech Republic, back then called Brünn and part of Austria-Hungary. Korngold’s story is highly unusual. He was an amazing child prodigy, and in his youth was compared to Mozart. At the age of nine he showed his cantata, Gold, to Gustav Mahler, who pronounced him a musical genius and suggested that Korngold study with Alexander von Zemlinsky. At the age of 11 he composed a ballet, which was staged at the Vienna Opera in 1910 and performed for the Emperor Franz Josef. He wrote his first orchestral piece when he was 14 and then at 17 not just one but two operas. When he was 23 he composed Die tote Stadt (The Dead City), a major opera. At that time Korngold was so famous that opera theaters competed to premier his work. In the end, it was performed simultaneously in two cities, Hamburg and Cologne (in Cologne the conductor was none other than Otto Klemperer). Later on the Nazis banned the opera (Korngold was Jewish), and it disappeared from the repertoire of the major houses. Die tote Stadt wаs revived about 30 years ago and these days is staged often. In 1923 he wrote a Concerto for Piano Left Hand for pianist Paul Wittgenstein, who lost his right hand in World War I (Ravel also wrote his famous Concerto for the Left Hand for Wittgenstein, as did Prokofiev with his concerto no. 4, although Wittgenstein never performed it). In 1934 Korngold was invited to write music for theater and film in Hollywood, which he did very successfully. He returned to Austria, but in 1938 Warner Brothers invited him back to compose the music to a new Errol Flynn movie called The Adventures of Robin Hood. While he was in California, Hitler and his army entered Austria in what became known as Anschluss (later on Korngold would say that Robin Hood saved his life). He continued writing film scores, very successfully until 1946, but that whole period was lost to the classical music. He returned to classical composition with the Violin Concerto (premiered in 1947), but his style, rich, melodic and highly romantic, was completely out of vogue: it was way behind the Second Viennese School of Schoenberg and his disciples, behind Stravinsky, Bartok and so many others. Music critics considered him a “film composer,” a disdainful designation. It’s hard to imagine a greater transformation than what Korngold’s reputation underwent, from “genius” to a complete “has-been.” The last 40 years saw somewhat of a rehabilitation: several of his operas were staged and recorded, the violin concerto became popular again, and so did some of his symphonic works. It’s clear that Korngold never fulfilled the great promise of his early years; nonetheless, he was a composer of talent, even if this talent didn’t quite fit the musical developments of the 20th century. Here is Marietta’s Lied from Die tote Stadt, sung by the incomparable Renée Fleming. And here Hilary Hahn performs Korngold’s Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35. Deutsche Symphonie Orchestra is conducted by Kent Nagano.

was born on May 29, 1897 in Brno, the capital of Moravia in the Czech Republic, back then called Brünn and part of Austria-Hungary. Korngold’s story is highly unusual. He was an amazing child prodigy, and in his youth was compared to Mozart. At the age of nine he showed his cantata, Gold, to Gustav Mahler, who pronounced him a musical genius and suggested that Korngold study with Alexander von Zemlinsky. At the age of 11 he composed a ballet, which was staged at the Vienna Opera in 1910 and performed for the Emperor Franz Josef. He wrote his first orchestral piece when he was 14 and then at 17 not just one but two operas. When he was 23 he composed Die tote Stadt (The Dead City), a major opera. At that time Korngold was so famous that opera theaters competed to premier his work. In the end, it was performed simultaneously in two cities, Hamburg and Cologne (in Cologne the conductor was none other than Otto Klemperer). Later on the Nazis banned the opera (Korngold was Jewish), and it disappeared from the repertoire of the major houses. Die tote Stadt wаs revived about 30 years ago and these days is staged often. In 1923 he wrote a Concerto for Piano Left Hand for pianist Paul Wittgenstein, who lost his right hand in World War I (Ravel also wrote his famous Concerto for the Left Hand for Wittgenstein, as did Prokofiev with his concerto no. 4, although Wittgenstein never performed it). In 1934 Korngold was invited to write music for theater and film in Hollywood, which he did very successfully. He returned to Austria, but in 1938 Warner Brothers invited him back to compose the music to a new Errol Flynn movie called The Adventures of Robin Hood. While he was in California, Hitler and his army entered Austria in what became known as Anschluss (later on Korngold would say that Robin Hood saved his life). He continued writing film scores, very successfully until 1946, but that whole period was lost to the classical music. He returned to classical composition with the Violin Concerto (premiered in 1947), but his style, rich, melodic and highly romantic, was completely out of vogue: it was way behind the Second Viennese School of Schoenberg and his disciples, behind Stravinsky, Bartok and so many others. Music critics considered him a “film composer,” a disdainful designation. It’s hard to imagine a greater transformation than what Korngold’s reputation underwent, from “genius” to a complete “has-been.” The last 40 years saw somewhat of a rehabilitation: several of his operas were staged and recorded, the violin concerto became popular again, and so did some of his symphonic works. It’s clear that Korngold never fulfilled the great promise of his early years; nonetheless, he was a composer of talent, even if this talent didn’t quite fit the musical developments of the 20th century. Here is Marietta’s Lied from Die tote Stadt, sung by the incomparable Renée Fleming. And here Hilary Hahn performs Korngold’s Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35. Deutsche Symphonie Orchestra is conducted by Kent Nagano.

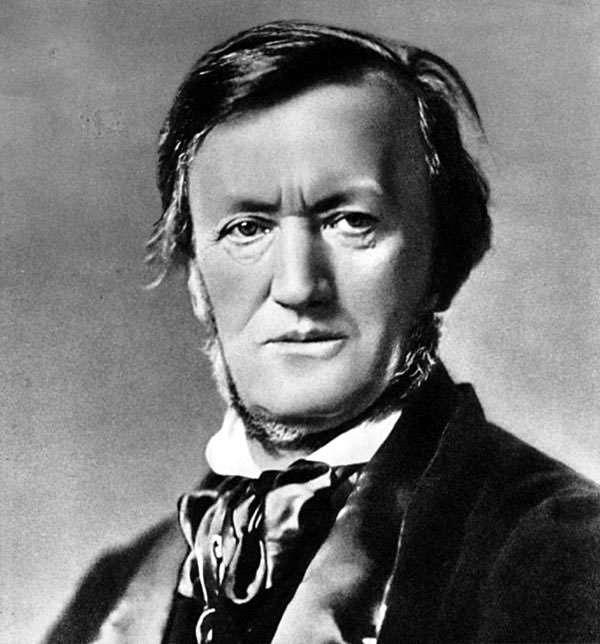

PermalinkMay 20, 2013. Richard Wagner 200. Richard Wagner, this most exasperating of musical geniuses, was born on May 22, 1813 in Leipzig. He was one of the most influential composers of the 19th century; the list of musicians indebted to Wagner is enormous, from Anton Bruckner, Gustav Mahler, Hugo Wolf and early Arnold Schoenberg in Germany to César Franck, Ernest Chausson, Jules Massenet and Claude Debussy in the francophone world (Debussy struggled with Wagner’s influence for years). And it went well beyond opera: philosophers, starting with Friedrich Nietzsche, poets, such as Baudelaire, Mallarmé and Verlaine, also writers, too many to mention, even painters fell under his spell. Wagner had his detractors too: the German music world at the time was divided into “Wagnerites” on one side and followers of Brahms on the other. Eduard Hanslick, an influential music critic, was an enemy. Wagner was probably the only composer for whom an opera house was built: King Ludwig II of Bavaria, his major patron, helped to finance its construction in Bayreuth. It was completed in 1876, just in time for the permier of Der Ring des Nibelungen cycle. Wagner was also a notorious anti-semite and racist, but of course we cannot hold him responcible for the Nazi’s appropriation of his music half a century later.

Schoenberg in Germany to César Franck, Ernest Chausson, Jules Massenet and Claude Debussy in the francophone world (Debussy struggled with Wagner’s influence for years). And it went well beyond opera: philosophers, starting with Friedrich Nietzsche, poets, such as Baudelaire, Mallarmé and Verlaine, also writers, too many to mention, even painters fell under his spell. Wagner had his detractors too: the German music world at the time was divided into “Wagnerites” on one side and followers of Brahms on the other. Eduard Hanslick, an influential music critic, was an enemy. Wagner was probably the only composer for whom an opera house was built: King Ludwig II of Bavaria, his major patron, helped to finance its construction in Bayreuth. It was completed in 1876, just in time for the permier of Der Ring des Nibelungen cycle. Wagner was also a notorious anti-semite and racist, but of course we cannot hold him responcible for the Nazi’s appropriation of his music half a century later.

Wagner wrote some symphonic music, none of it very successul. His genius was fully realized in his operas, from the early Rienzi (1842) and The Flying Dutchman (1843), to Tannhäuser (1845) and Lohengrin (1850). He started writing the story of Siegfried's Death in 1848. He eventually expanded and rewrote the original libretto and turned it into the cycle of four operas called Der Ring des Nibelungen. He started composing the first opera of the cycle, Das Rheingold, in 1853 and completed the Cycle in 1874 with Götterdämmerung. In 1857 he temporarily stopped working on the Cycle and wrote one of his greatest creations, the mesmerizing Tristan und Isolde. Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg followed in 1868. His last opera, Parsifal, was written in 1882, less than a year before his death in Venice in February of 1883. His body was taken by gondola and then by train to Germany. He was buried in Bayreuth.

The singing roles in Wagner operas are extremely demanding, and require exceptional physical stamina. Most of the operas are very (some might say excruciatingly) long: Die Meistersinger has about four and a half hours of music, Parsifal is not much shorter, both Tristan und Isolde and Sigfried are about four hours long without an intermission. Wagner’s operas also require a very special clarity of tone, with practically no vibrato. Wagnerian tenors, possessing power, richness of voice and drama, became known as Heldentenor, “heroic tenor” in German. Probably the most famous Heldentenor of the 20th century was Lauritz Melchior. Siegfried Jerusalem, who recently finished his operatic career, and Ben Heppner, still quite active, are among the noted Heldentenors. Wagner also created great (and very challenging) soprano roles; for example Brünnhilde in the four operas of the Ring, Isolde in Tristan, and Kundry in Parsifal. Kirsten Flagstad and Birgit Nilsson were incomparable Wagnerian sopranos. Jane Eaglen and Deborah Voight are active today and perform admirably in major opera theaters.

Here’s the Prelude to Act I of Tristan und Isolde, recorded in 1952 by Wilhelm Furtwangler and Philharmonia Orchestra (it was very effectively used by Lars von Trier in his film Melancholia). From the same opera, the German soprano Waltraud Meier sings the famous Isolde Liebestod (here). And here is an excerpt from the legendary 1935 recording of Die Walküre with Lauritz Melchior and Lotte Lehmann. Bruno Walter conducts the Vienna Philarmonic.

Permalink