Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

October 28, 2013. Paganini and Bellini. We should’ve written about Niccolò Paganini last week, as his birthday was October 27th, but we had Liszt, Bizet, and Domenico Scarlatti to celebrate and just ran out of space. Paganini was born in 1782 in Genoa. At the age of five he started studying the mandolin with his father, who was in the shipping business.jpg) but played mandolin on the side. Two years later Niccolò switch to the violin. He went to several local violin teachers, but it became clear that his abilities far outstriped theirs. His father took Niccolò to Parma, to play for the famous violinist, teacher and composer Alessandro Rolla, who in turn referred him to other violin teachers. When the French invaded Italy, Paganini left the occupied Genoa and settled in Lucca, then a republic. Napoleon gave Lucca to his sister Elisa, and eventually made her the Grand Duchess of Tuscany, and Paganini for a while became part of her entourage. All along, Paganini was mostly interested in concretizing. In 1797, accompanied by his father, he went on a highly successful tour of Lombardy. He also became quite popular with the public in Parma and his native Genoa. Gaining financial independence, he indulged in gambling and numerous love affairs. At some point he had to pawn his violin to cover debts; a French merchant loaned him a Guarneri violin to play a concert, and upon hearing him was so impressed that he refused to take it back. It became his favorite instrument.

but played mandolin on the side. Two years later Niccolò switch to the violin. He went to several local violin teachers, but it became clear that his abilities far outstriped theirs. His father took Niccolò to Parma, to play for the famous violinist, teacher and composer Alessandro Rolla, who in turn referred him to other violin teachers. When the French invaded Italy, Paganini left the occupied Genoa and settled in Lucca, then a republic. Napoleon gave Lucca to his sister Elisa, and eventually made her the Grand Duchess of Tuscany, and Paganini for a while became part of her entourage. All along, Paganini was mostly interested in concretizing. In 1797, accompanied by his father, he went on a highly successful tour of Lombardy. He also became quite popular with the public in Parma and his native Genoa. Gaining financial independence, he indulged in gambling and numerous love affairs. At some point he had to pawn his violin to cover debts; a French merchant loaned him a Guarneri violin to play a concert, and upon hearing him was so impressed that he refused to take it back. It became his favorite instrument.

Between 1801 and 1805 Paganini composed 24 Capricci for unaccompanied violin, which, with his violin concertos, remain his most popular compositions. In the following years he often performed his own music, which was beyond the technical abilities of most violinists of the time. That was also the period when he competed for fame with the French violinist Charles Philippe Lafont and the German Louis Spohr. His 1813 concerts in Milan’s La Scala were sensational; still, for the next following years he played mostly in Italy. In 1828 he went on a tour to Vienna and had tremendous success. The concerts in Paris and London followed and were equally successful. He became a wealthy man and settled in Paris in 1833. There, he commissioned Hector Berlioz a symphony, Harold in Italy, with extended viola solos (he never thought much of them technically and never played the symphony). He also invested in a gambling house, which went bust soon after, ruining Paganini financially: he had to sell his violins and personal belongings. The legends surrounding him grew to a fantastic degree: he was rumored to have been imprisoned for murder and to be in a league with the devil (the only thing really devilish was the difficulty of his compositions). Paganini, who stopped performing in 1834, died in 1840. Some years earlier he was treated for syphilis and tuberculosis but it seems that the cause of his death was internal hemorrhaging. He died suddenly, without receiving last rights; because of this and his rumored association with dark forces (but also because of the innate backwardness of the 19th century Italian church), he was denied a Catholic burial. His remains were transported to Genoa but not interred. Only in 1876 was he laid to rest, not in Genoa but in Parma.

During his life, Paganini owned a number of violins made by the great masters: several Guarneris, a Nicolò Amati and several Stradivari instruments. All of them are highly sought after; the Tokyo String Quartet plays four of his instruments. Paganini’s favorite violin, Il Cannone (The Cannon), was made in 1742 by Giuseppe Antonio Guarneri del Gesù and is now considered an Italian national treasure. The winner of the Paganini violin competition is allowed to play it- a great honor. Here is Itzhak Perlman playing Paganini's Caprice for solo violin no. 1, op.1 No.1 in E Major, L'Arpeggio. It was recorded in 1972.

We’ll write about Vincenzo Bellini, another Italian and a contemporary of Paganini’s, next week. For now, here’s the aria Care compaggne followed by Come per me sereno from La Sonnambula. It’s sung, beautifully, by the Russian soprano Anna Netrebko.Permalink

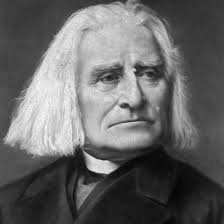

October 21, 2013. Liszt, Bizet, Scarlatti. October 22nd marks the 202nd birthday of the great Hungarian composer and pianist Franz Liszt. Liszt, who lived a long life (he died in 1886, at almost 75 years of age), went through many phases during the years. He started as a brilliant piano virtuoso traveling all across Europe, but eventually stopped performing to concentrate on composition. In his youth he was an idol and lover of many brilliant women (including George Sand) but in later years he joined the Order of St. Francis. In the last 20 years of his life, Liszt’s compositional style also changed dramatically. It became more reflective, economic, and often experimental: he used atonality and unusual harmonies years before Viennese composers introduced such techniques in the first decade of the 20th century. Compare, for example, the brilliant showmanship of his Transcendental Etudes, which Liszt started composing in his youth and completed in 1852 (here is Etude No.5 in B-flat major, "Feux Follets," performed by Boris Berezovsky), to such impressionistic, introverted composition as Nuages gris, a piano piece he wrote in 1881 (Carlos Gallardo on the piano). No wonder Claude Debussy admired this piece.

piano virtuoso traveling all across Europe, but eventually stopped performing to concentrate on composition. In his youth he was an idol and lover of many brilliant women (including George Sand) but in later years he joined the Order of St. Francis. In the last 20 years of his life, Liszt’s compositional style also changed dramatically. It became more reflective, economic, and often experimental: he used atonality and unusual harmonies years before Viennese composers introduced such techniques in the first decade of the 20th century. Compare, for example, the brilliant showmanship of his Transcendental Etudes, which Liszt started composing in his youth and completed in 1852 (here is Etude No.5 in B-flat major, "Feux Follets," performed by Boris Berezovsky), to such impressionistic, introverted composition as Nuages gris, a piano piece he wrote in 1881 (Carlos Gallardo on the piano). No wonder Claude Debussy admired this piece.

A generous man, Liszt was a benefactor of many composers; first and foremost of Richard Wagner, a friend and, later, his son-in-law (interestingly, Wagner was just two years younger than Liszt and 24 years older than his daughter Cosima). He also promoted the music of Hector Berlioz, Edvard Grieg, Alexander Borodin and many others. He wrote a prodigious number of transcriptions, often popularizing the music of composers he admired. An unusual transcription was written in 1879, Sarabande and Chaconne from Handel's opera Almira, S. 181. In his earlier period Liszt wrote many transcriptions of Bach’s organ works, but this Handel is the only baroque piece transcription from his later years. Handel changed the sequence of dances and wrote some additional music; in this respect it’s more of an original work than a transcription. Sarabande is performed by the Danish-American pianist and composer, Gunnar Johansen. Johansen, who died in 1991, was one of the first pianists who attempted to record all of Liszt’s music. He didn’t record all of it but 51 LPs is a prodigious effort (Leslie Howard, the Australian-American virtuoso, did record all of Liszt on 97 CDs). You can listen this 1948 recording of Sarabande here.

Domenico Scarlatti was born on October 26, 1685 in Naples. He composed 555 keyboard sonatas, and many of them are absolutely brilliant. During his lifetime "keyboard" usually meant the harpsichord, but these days they are often performed on modern piano. Some of the greatest pianists of the 20th century were great admirers of Scarlatti and performed his music: Vladimir Horowitz, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli and Emil Gilels all played and recorded Scarlatti’s sonatas. These days the Canadian pianist Marc-André Hamelin excels as a foremost interpreter. Here’s Sonata in b minor, K. 27, played (live, in March of 1955) by Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli (the great technician Emil Gilels takes almost twice as long to play it: 5 minutes instead of Michelangeli’s 2:45).

Finally, Georges Bizet was also born this week, on October 25th of 1838. We dedicated an entry to him a year ago, so this time we’ll just listen to one of his most popular duets. Bizet wrote the opera Les pêcheurs de perles (The Pearl Fishers) when he was just 25. It had one run at the Théâtre Lyrique in Paris and was not revived during Bizet’s lifetime. These days the duet from the opera is one of the most famous and often performed numbers. Here is the 1950 recording with one of the greatest tenors of the 20th century, Jussi Björling, and the wonderful American baritone Robert Merrill. Renato Cellini conducts the RCA Victor Symphony Orchestra.Permalink

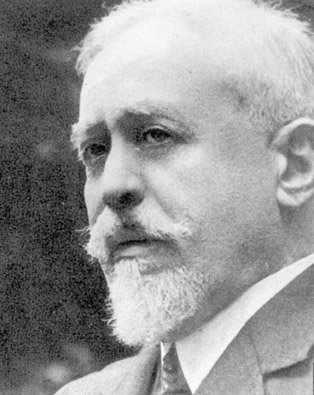

October 14, 2013. Alexander von Zemlinsky and Camille Saint-Saëns. The Austrian composer Alexander von Zemlinsky was born on this day in 1871. Zemlinsky’s music, tonal in its core, was influenced by Brahms and, to an extent, by Mahler. Quite influential in the first half of the 20th century, Zemlinsky lost some of his appeal in the era of the atonal and twelve-tonal music popularized by the followers of the Second Viennese school. Lately, however, he’s experienced a minor comeback and is being played more often. Zemlinsky was born in Vienna into an unusual family: his father was a Roman Catholic; his mother was born in Sarajevo to a Sephardic Jewish father and a Bosnian Muslim mother. Eventually the whole family converted to Judaism, and Alexander was raised Jewish. The noble “von” addition to the family name was his father’s invention and not bestowed by the Emperor. Zemlinsky studied piano as a child, played organ in a synagogue, and went to the Vienna Conservatory at the age of 13. Johannes Brahms, upon hearing his Symphony in D, became a supporter and introduced the young composer to his publisher, Simrock, as he did 20 years earlier with the young Dvořák. In 1895 Zemlinsky met Arnold Schoenberg and they became fast friends (some years later Schoenberg married Zemlinsky’s sister Mathilde). Zemlinsky was just three years older than Schoenberg, but he was a natural teacher and gave him several lessons in counterpoint, the only music lessons Schoenberg ever received. In 1900 Zemlinsky fell in love with his student, 21 year-old Alma Schindler. For two years they conducted a passionate (but apparently unconsummated) affair, until Alma decided to break up with Zemlinsky and marry Gustav Mahler, who was then 42 but famous. The fact that Zemlinsky was Jewish also played a role; Mahler, born Jewish, had converted to Catholicism five years earlier. In 1905 Zemlinsky wrote the symphonic poem Die Seejungfrau (The Mermaid); the musicologist Antony Beaumont writes that it was an attempt to heal the trauma caused by the break-up. This being Vienna, it had an unusual psychological twist: Zemlinksy saw himself as a mermaid and Alma as the Prince. You can listen to Die Seejungfrau in the performance by the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, Ricardo Chailly conducting.

by Mahler. Quite influential in the first half of the 20th century, Zemlinsky lost some of his appeal in the era of the atonal and twelve-tonal music popularized by the followers of the Second Viennese school. Lately, however, he’s experienced a minor comeback and is being played more often. Zemlinsky was born in Vienna into an unusual family: his father was a Roman Catholic; his mother was born in Sarajevo to a Sephardic Jewish father and a Bosnian Muslim mother. Eventually the whole family converted to Judaism, and Alexander was raised Jewish. The noble “von” addition to the family name was his father’s invention and not bestowed by the Emperor. Zemlinsky studied piano as a child, played organ in a synagogue, and went to the Vienna Conservatory at the age of 13. Johannes Brahms, upon hearing his Symphony in D, became a supporter and introduced the young composer to his publisher, Simrock, as he did 20 years earlier with the young Dvořák. In 1895 Zemlinsky met Arnold Schoenberg and they became fast friends (some years later Schoenberg married Zemlinsky’s sister Mathilde). Zemlinsky was just three years older than Schoenberg, but he was a natural teacher and gave him several lessons in counterpoint, the only music lessons Schoenberg ever received. In 1900 Zemlinsky fell in love with his student, 21 year-old Alma Schindler. For two years they conducted a passionate (but apparently unconsummated) affair, until Alma decided to break up with Zemlinsky and marry Gustav Mahler, who was then 42 but famous. The fact that Zemlinsky was Jewish also played a role; Mahler, born Jewish, had converted to Catholicism five years earlier. In 1905 Zemlinsky wrote the symphonic poem Die Seejungfrau (The Mermaid); the musicologist Antony Beaumont writes that it was an attempt to heal the trauma caused by the break-up. This being Vienna, it had an unusual psychological twist: Zemlinksy saw himself as a mermaid and Alma as the Prince. You can listen to Die Seejungfrau in the performance by the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, Ricardo Chailly conducting.

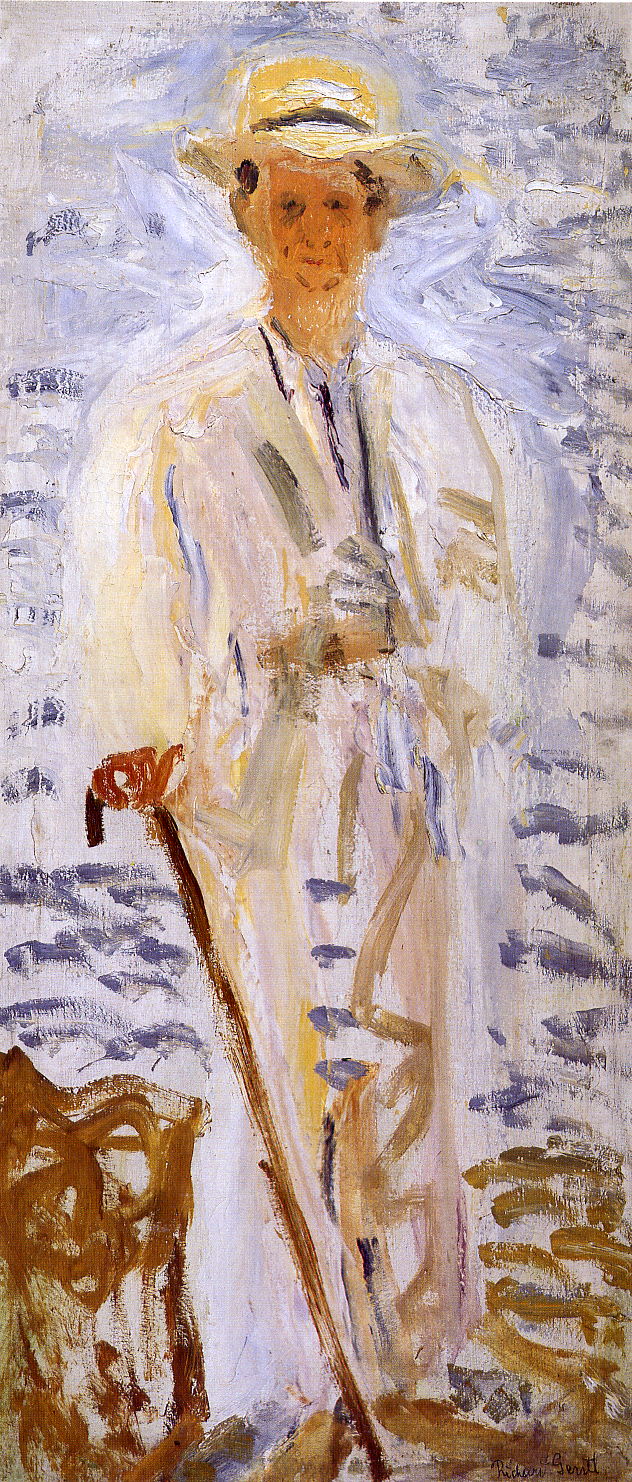

The portrait of Zemlinsky, above, was made in the summer of 1907 by one Richard Gerstl, a young Austrian painter. Gerstl joined Zemlinksy and the Schoenbergs on vacation in Gmunden on lake Traunsee. He made several portraits of the Schoenbergs and one of Zemlinsky and even taught Arnold to paint. At some point during the summer Gerstl became Mathilde Schoenberg’s lover. One year later, all of them were back in Gmunden, with the love affair in full swing. One day Arnold found them in a compromising situation, and Mathilde and Gerstl escaped to Vienna. Anton Webern, Schoenberg’s pupil and friend of the family, convinced Mathilde to return to Arnold. Gerstl found himself ostracized and completely isolated. On October 4th of 1908 he set his studio on fire and hanged himself in front of a mirror.

Camille Saint-Saëns was born last week (his birthday is October 9, 1835) but we were too busy celebrating Verdi’s 200th anniversary. Saint-Saëns lived a long life: he died in 1921. To put it into perspective: in 1849, when Chopin died, Saint-Saëns was 14 and had already written several pieces; by the time of Saint-Saëns’s death in 1921 Stravinsky and Schoenberg had already written some of their most important, transformative compositions. No wonder that Saint-Saëns, who started as a pioneer, embracing the music of Wagner and Liszt, ended up being an arch-conservative, fighting even Debussy and Ravel (he stormed out of the first concert performance of The Right of Spring and declared Stravinsky “mad”). Saint-Saëns’s music was never very deep, but he wrote wonderful melodies and often managed to create coherently developed musical structures. Quite a number of his compositions remain popular, for example The Carnival of the Animals, the Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso for violin and orchestra, some of his piano concertos (he wrote five), and his opera Samson. You can hear Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso, Op. 28 in the performance by the great violinist Jascha Heifetz, with RCA Victor Symphony Orchestra, William Steinberg conducting.Permalink

October 7, 2013

Verdi 200! This is a very special occasion: on October 10 the great master of Italian opera, Giuseppe Verdi, turns 200 (he might have been born on October 9, but what does it matter!). We’re poor on Verdi’s music: opera houses don’t share their recorded operas with us, neither do the major labels, so all we can do to celebrate is borrow from YouTube. We’ve previously written about Verid’s life, so today we’ll just present four magnificent selections from his operas Rigoletto, La Traviata, Il Trovatore, and Aida. Rigoletto was composed in 1851. Verdi was a well-known composer by then, but Rigoletto, written for and premiered at the Venetian theater La Fenice, was an unparallel success. The next day people sung the Duke’s aria La donna è mobile on the streets. Enrico Caruso, one of the most famous Dukes, and Nellie Melba performed the opera in 1902 in the Covent Garden. The quartet Bella figlia dell'amore (Beautiful daughter of love) from Act III is one of the highlights of the opera. Here it is, with Joan Sutherland, still in her prime at 61, as Gilda, Luciano Pavarotti, in great form as the Duke, Leo Nucci as Rigoletto and Isola Jones as Maddalena (we cut out most of the ovation, which ran for six minutes straight, more than the Quartet itself).

all we can do to celebrate is borrow from YouTube. We’ve previously written about Verid’s life, so today we’ll just present four magnificent selections from his operas Rigoletto, La Traviata, Il Trovatore, and Aida. Rigoletto was composed in 1851. Verdi was a well-known composer by then, but Rigoletto, written for and premiered at the Venetian theater La Fenice, was an unparallel success. The next day people sung the Duke’s aria La donna è mobile on the streets. Enrico Caruso, one of the most famous Dukes, and Nellie Melba performed the opera in 1902 in the Covent Garden. The quartet Bella figlia dell'amore (Beautiful daughter of love) from Act III is one of the highlights of the opera. Here it is, with Joan Sutherland, still in her prime at 61, as Gilda, Luciano Pavarotti, in great form as the Duke, Leo Nucci as Rigoletto and Isola Jones as Maddalena (we cut out most of the ovation, which ran for six minutes straight, more than the Quartet itself).

La Traviata was composed just two years later, in 1853. It’s based on a then very popular novel by Alexandre Dumas fils, La Dame aux camélias (The Lady of the Camellias), a tragic love story of a courtesan suffering from tuberculosis and a provincial bourgeois. The novel was adapted for the theater, and Verdi saw the play during his visit to Paris in 1852. The libretto was written by Verdi’s favorite, Francesco Maria Piave (he also wrote the libretto for Rigoletto). Margurite of Dumas became Violetta, and Armand – Alfredo. Here is the famous duet from Act III: Parigi, o cara, noi lasceremo ("We will leave Paris, O beloved"). Alfredo is Jose Carreras and Violetta – the incomparable Renata Scotto.

The years 1851 through 1854 were incredibly productive for Verdi. He worked on Il Trovatore and La Traviata practically at the same time: the former was premiered on January 19, 1983, the latter – on March 6. Il Trovatore (The Troubadour) was based on a play by the Spanish dramatist Antonio García Gutiérrez. Set in the 15th century, Il Trovatore tells a complicate story of Manrico, the troubadour; Count di Luna, a nobleman; Leonora, who is in love with Manrico but is pursued by di Luna, and Azucena, a gipsy. In Act IV, with both Manrico and Azucena being imprisoned by di Luna, Leonora begs him to free them. This duet, Miserere (Lord, Thy mercy on this soul) is performed by Maria Callas, La Divina, probably the most expressive soprano of the 20th century and a perfect Leonora, and Tito Gobbi, one of the greatest Verdi baritones.

Aida was written almost 20 years later, in 1871. The opera was commissioned by Ismail Pasha, the Ottoman Governor of Egypt. It was premiered in Cairo and then staged, to enormous success, in all major opera theaters of the world, from Teatro Colon in Buenos-Aires to the Vienna State Opera to the Covent Garden in London and Mariinsky in St-Petersburg. The story is set in ancient Egypt. Aida, the Ethiopian princess, is captured by the Egyptians. Radames, Egypt’s military commander, falls in love with her. Unfortunately for both of them, the Pharaoh’s daughter Amneris loves Radames. In the end, Radames is put on trial for treason, then sealed up in a dark vault and left there to die. There he finds Aida who, in longing to share his fait, hid in what would become their tomb. They bid farewell to life and sing of their love. On top of the vault, Amneris weeps and prays. You can hear the "Tomb scene" as performed by the supreme singers, Montserrat Caballé and Plácido Domingo. Fiorenza Cossotto is Amneris. Riccardo Muti leads the New Philharmonia Orchestra.

The music in the four excerpts above runs for just 20 minutes, but it is 20 minutes of pure genius. Viva maestro and Buon compleanno!

September 30, 2013. Paul Dukas and Marc-Antoine Charpentier. The French composer Paul Dukas is know mostly for his orchestral poem The Sorcerer's Apprentice, but it’s such a lovely piece that it alone places Dukas’ name alongside the best French composers of the late 19th century. Paul Dukas was born in Paris on October 1, 1865 into a well to do Jewish family; his father was a banker. Apparently Dukas didn’t show any special musical talents till the age of 14, when, while recovering from an illness, he started composing. Two years later he entered the Paris Conservatory, where he met Claude Debussy; the two became close friends. In 1888, Dukas failed to win the prestigious Prix du Rome (Debussy had won it four years earlier) and disappointed, left the Conservatory. After a stint in the army he started his second career as a music critic. As a composer, Dukas was very self-conscious and, if dissatisfied, would destroy his own music: the list of pieces he rejected is almost as long as those that he published. His first big composition, Symphony in C Major, was premiered in1896 to mixed reviews. Then, a year later, he wrote The Sorcerer's Apprentice, a symphonic piece inspired by Goethe’s poem by the same name. The poem describes an apprentice of an old sorcerer, who, when left alone, performs small magic, making a broom fetch water for him. Unfortunately, he doesn’t know how to break the spell and almost drowns, but the old sorcerer arrives just in time to restore order. The work is programmatic and almost literally descriptive in the way it follows the development of Goethe’s poem (in this it reminds one of Richard Strauss’s Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks, with it’s Till’s theme and the representation of people and events). The music immediately became very popular, eclipsing everything else Dukas wrote either before or after. In 1899 he composed a rather successful opera Ariane et Barbe-bleue. He continued writing music till 1912, after which he turned to teaching. Maurice Duruflé, Olivier Messiaen, Manuel Ponce, Joaquín Rodrigo were among his students. Dukas died in 1935 aged 69. You can hear The Sorcerer's Apprentice in the recording by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Jesús López-Cobos conducting.

French composers of the late 19th century. Paul Dukas was born in Paris on October 1, 1865 into a well to do Jewish family; his father was a banker. Apparently Dukas didn’t show any special musical talents till the age of 14, when, while recovering from an illness, he started composing. Two years later he entered the Paris Conservatory, where he met Claude Debussy; the two became close friends. In 1888, Dukas failed to win the prestigious Prix du Rome (Debussy had won it four years earlier) and disappointed, left the Conservatory. After a stint in the army he started his second career as a music critic. As a composer, Dukas was very self-conscious and, if dissatisfied, would destroy his own music: the list of pieces he rejected is almost as long as those that he published. His first big composition, Symphony in C Major, was premiered in1896 to mixed reviews. Then, a year later, he wrote The Sorcerer's Apprentice, a symphonic piece inspired by Goethe’s poem by the same name. The poem describes an apprentice of an old sorcerer, who, when left alone, performs small magic, making a broom fetch water for him. Unfortunately, he doesn’t know how to break the spell and almost drowns, but the old sorcerer arrives just in time to restore order. The work is programmatic and almost literally descriptive in the way it follows the development of Goethe’s poem (in this it reminds one of Richard Strauss’s Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks, with it’s Till’s theme and the representation of people and events). The music immediately became very popular, eclipsing everything else Dukas wrote either before or after. In 1899 he composed a rather successful opera Ariane et Barbe-bleue. He continued writing music till 1912, after which he turned to teaching. Maurice Duruflé, Olivier Messiaen, Manuel Ponce, Joaquín Rodrigo were among his students. Dukas died in 1935 aged 69. You can hear The Sorcerer's Apprentice in the recording by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Jesús López-Cobos conducting.

We’ll stay in France for a little longer to salute another composer who lived two centuries earlier: Marc-Antoine Charpentier (who should not be confused with another Charpentier, Gustave, a contemporary of Dukas and the author of the opera Louise). We don’t know his date of birth, except that it was in 1643. Marc-Antoine was probably born in Paris, got a good education and spent some time in Rome, studying with the then-famous Roman composer Giacomo Carissimi. Upon returning to Paris he found employment at the court of Mademoiselle Guise, the daughter of Charles, Duke of Guise and a cousin of King Louis XIV. Charpentier lived and worked in Hôtel de Guise for the next 17 years. He wrote music to the plays of Molière and Corneille and had his operas staged, even though Jean Baptiste Lully had a virtual monopoly over theatrical music. In 1679 Charpentier became the court composer for Grand Dauphin, the eldest son of the King and in 1698 he was appointed maître de musique for the Royal choir of Sainte-Chapelle. Charpentier died on February 24, 1704 in Sainte-Chapelle and was buried in the cemetery behind the choir. Here is one of the most famous of Charpentier’s compositions, the motet Te Deum. Charpentier wrote several settings, all between 1688 and 1698. This performance is by the Orchestra and the chorus of Accademia Nazionale Di Santa Cecilia, Myung-Whun Chung conducting.

PermalinkSeptember 23, 2013. Jean-Philippe Rameau and Dmitry Shostakovich. Two composers, both major figures during their lifetime, were born this week. One dominated the music scene during the reign of French King Louis XV, another was considered, officially (if not always), the greatest composer of the Soviet Union. That’s where the parallel ends however; it’s not just that two and a half centuries separate them: Rameau lived during the most brilliant period of French history; Shostakovich’s time was one of the most oppressive in all of the history of Russia. Jean-Philippe Rameau was born on September 25, 1683, when Louis XIV the Sun King ruled France, but he didn’t come to age as a composer till the 1720s; by then Louis XIV’s son was king. Rameau was approaching 50 when he wrote his first opera, but once he started, he wouldn’t write anything else. He wrote more than 30, and in toto they represent a major development in music history of the 18th century. His very first opera Hippolyte et Aricie, written in 1733, was premiered at the Palais-Royal, his second, Samson, had none other than Voltaire as the librettist. (Unfortunately, it was never performed, even though it went into rehearsals, and its score has been lost). The third opera, Les Indes galantes, was a big success. A curious historical anecdote relates to this opera. In 1725 the French settlers convinced several Indian chiefs, Agapit Chicagou among them, to go to Paris. Many Indian chiefs decided to travel to France, but as they were about to board the ship, it sunk; after the accident, most of the chiefs returned home. Apparently the ones who went had a good time in Paris and eventually were brought to Fontainebleau, were they met with the King. The chiefs pledged allegiance to the French crown, and later performed ritual dances at the Theatre Italien. Rameau was inspired by this event; the fourth act (entrées) of Les Indes galantes is called Les Sauvages and tells the story of a daughter of an Indian chief being pursued by a Spaniard and a Frenchmen.

Rameau wrote his 13th opera, Zaïs, in 1748. The highly imaginative Overture to the opera depicts the emergence of the four elements,Earth, Water, Air, and Fire, out of chaos. You can hear it in the performance by Les Musiciens Du Louvre under the direction of Marc Minkowski.

Dmitry Shostakovich, who was also born on September 25, 1906 in St.-Petersburg, Russia, is known mostly as a symphonist. This reputation is totally deserved: Shostakovich wrote 15 symphonies, many of them are among the most important music of the 20th century. He also wrote 15 string quartets, and often these were much more personal, less affected by the events of the day. In 1936 his opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, which initially was hailed by the Soviet propaganda machine as a “result of the correct policy of the Party,” fell out of favor. The opera was denounced in Pravda. The same year, in a frightening episode, Shostakovich went to the Bolshoi Theater for a performance of Lady Macbeth only to find Stalin and members of the Politburo in the main box. To his horror they cringed as the music got loud and laughed during the love scenes. Shostakovich was “white as a sheet” when he took bows at the end of the opera. The Great Terror was gaining speed; many of Shostakovich’s friends, including his major patron, Marshal Tukhachevsky, were arrested and shot. His Fourth symphony was banned (officially, Shostakovich withdrew it voluntarily). Scared for his life, he wrote the Fifth Symphony in a much more conservative manner, and it was a great success, both with the public and the officials. This restored Shostakovich’s reputation: the official line was that he learned from his mistakes. That was when Shostakovich composed his first string quartet: the more chamber setting allowed him to experiment with the musical ideas he would not dare to expose in a symphony. You can hear the Quartet no. 1 in C Major op. 49 in the performance by the Borodin Quartet, a great ensemble with which Shostakovich collaborated for many years. This recording was made in 1978.Permalink

symphonies, many of them are among the most important music of the 20th century. He also wrote 15 string quartets, and often these were much more personal, less affected by the events of the day. In 1936 his opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, which initially was hailed by the Soviet propaganda machine as a “result of the correct policy of the Party,” fell out of favor. The opera was denounced in Pravda. The same year, in a frightening episode, Shostakovich went to the Bolshoi Theater for a performance of Lady Macbeth only to find Stalin and members of the Politburo in the main box. To his horror they cringed as the music got loud and laughed during the love scenes. Shostakovich was “white as a sheet” when he took bows at the end of the opera. The Great Terror was gaining speed; many of Shostakovich’s friends, including his major patron, Marshal Tukhachevsky, were arrested and shot. His Fourth symphony was banned (officially, Shostakovich withdrew it voluntarily). Scared for his life, he wrote the Fifth Symphony in a much more conservative manner, and it was a great success, both with the public and the officials. This restored Shostakovich’s reputation: the official line was that he learned from his mistakes. That was when Shostakovich composed his first string quartet: the more chamber setting allowed him to experiment with the musical ideas he would not dare to expose in a symphony. You can hear the Quartet no. 1 in C Major op. 49 in the performance by the Borodin Quartet, a great ensemble with which Shostakovich collaborated for many years. This recording was made in 1978.Permalink