Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

January 20, 2014. Dutilleux and Willaert. A year ago, when we celebrated Henri Dutilleux’s 96th birthday, he was living in Paris and still working. He died five months later, on May 22nd, leaving behind a major body of work, and already a classic. Dutilleux was born on January 22nd, 1916 in Anger in western France. He studied at the Paris Conservatory, graduating in 1938. After the War, he worked for many years at Radio France as the head of music production and left only in 1963 to dedicate himself to composing. In 1961 Alfred Cortot, the founder of École Normale de Musique de Paris, invited him to join the school. After Cortot’s death Dutilleux for a while served as the school’s president. Dutilleux assigned the first opus to his Piano Sonata, which he wrote for his wife, the pianist Geneviève Joy, in 1946-48, even though by then he had already been composing for at least 10 years. Even though he disavowed his earlier composition, his Sonatine for flute and piano (1943) is performed quite often.

head of music production and left only in 1963 to dedicate himself to composing. In 1961 Alfred Cortot, the founder of École Normale de Musique de Paris, invited him to join the school. After Cortot’s death Dutilleux for a while served as the school’s president. Dutilleux assigned the first opus to his Piano Sonata, which he wrote for his wife, the pianist Geneviève Joy, in 1946-48, even though by then he had already been composing for at least 10 years. Even though he disavowed his earlier composition, his Sonatine for flute and piano (1943) is performed quite often.

Although Dutilleux’s style was affected by Debussy and Ravel, he was a modernist who used atonality and complex rhythms. He was also a perfectionist, revising his compositions over and over. Here is Dutilleux’s sonorous Timbres, espace, movement (Timbre, space, movement), a 1978 composition for an unusual combination of instruments: woodwinds, brass, cellos, percussions, but no violins or violas. Timbres was commissioned by Mstislav Rostropovich, who gave the premier with the National Orchestra the same year. The piece carries a subtitle, “The Starry Night,” after the painting by Van Gogh. The Bordeaux Aquitaine National Orchestra is conducted by Hans Graf. And for someone who likes more austere music, here is his String quartet, Ainsi la nuit (“So the night”), which Dutilleux composed in 1976-76. It’s performed by the Belcea Quartet.

Adrian Willaert had an interesting life: a talented Franco-Flemish composer, he followed in the steps of Josquin des Prez, and then later established the Venetian musical school. Willaert was born in a small Flemish town of Rumbeke around 1490 (the same time as John Taverner, about whom we wrote last week). We know about his life from the writings of his student, the composer and music theorist Gioseffo Zarlino. Willaert went to Paris to study law but switched to music instead. One of his teachers was Jean Mouton, the composer of the Royal chapel. Around 1515 Willaert moved to Rome. Later, he entered the service of Cardinal Ippolito d'Este of Ferrara (it’s interesting that some years earlier Josquin was employed by Ippolito’s father, Ercole I d'Este, Duke of Ferrara). In 1527 Willaert received an exceptional appointment in Venice, becoming the maestro di cappella of the St. Mark cathedral. He held that post till his death in 1562. During that time he composed a large number of masses, motets, madrigals and other secular music. He also had many students, among them Andrea Gabrieli. Venetian music owes much to the architecture of St. Mark. The cathedral is unusual in that it has not one but two choir lofts, on each side of the main alter, with organs in both lofts. Willaert used this spatial separation to divide the choir in two and wrote “antiphonal” music, in which the melody is sung alternatively by both choirs. The Gabrielis, Andrea and Giovanni, made good use of it, and eventually this technique became known as Venetian polichoral style.

chapel. Around 1515 Willaert moved to Rome. Later, he entered the service of Cardinal Ippolito d'Este of Ferrara (it’s interesting that some years earlier Josquin was employed by Ippolito’s father, Ercole I d'Este, Duke of Ferrara). In 1527 Willaert received an exceptional appointment in Venice, becoming the maestro di cappella of the St. Mark cathedral. He held that post till his death in 1562. During that time he composed a large number of masses, motets, madrigals and other secular music. He also had many students, among them Andrea Gabrieli. Venetian music owes much to the architecture of St. Mark. The cathedral is unusual in that it has not one but two choir lofts, on each side of the main alter, with organs in both lofts. Willaert used this spatial separation to divide the choir in two and wrote “antiphonal” music, in which the melody is sung alternatively by both choirs. The Gabrielis, Andrea and Giovanni, made good use of it, and eventually this technique became known as Venetian polichoral style.

We’ll hear a beautiful madrigal by Willaert, O dolce vita mia, performed by the King’s Singers. And here is his motet Pater Noster as performed by another British ensemble, Magdala, directed by the founder, David Skinner.

PermalinkJanuary 2014. John Taverner and John Tavener. John Taverner, born around 1490 (the exact date is unknown), was one of the most significant composers of the early English Renaissance. John Dunstaple preceded him by 100 years, but Dunstaple exerted more influence on the burgeoning Burgundian music school than on the English one. On the other hand, many composers followed Taverner: Thomas Tallis, 15 years his junior, William Byrd (born around 1540), then Thomas Morley (1557), John Dowland and John Bull, both born around 1563, and many more. Taverner lived and worked during the reign of Henry VIII and the English Reformation and, as a religious composer, was strongly affected by changes that the Church of England underwent during that period. In 1526 Taverner went to Oxford to become the master of choir of the Christ Church College, then called Cardinal College, which had been recently organized by Cardinal Wolsey. Wolsey, for a time a highly influential advisor to the King, became a major patron; in one episode he saved Taverner from accusations of concealing “heretical books,” noting that Taverner was "but a musician." Wolsey fell into disfavor with the King and died in 1530 while on trial. Taverner left Oxford the same year. Later he was hired by Thomas Cromwell, the chief minister to King Henry and one of the major leaders of the Reformation. With Cromwell he took part in the dissolution of the monasteries; it seems that at that time he stopped composing altogether, so practically all the music he wrote was Catholic and pre-Reformation. Taverner wrote eight Masses, several Magnificats, and a large number of motets. One of his most important masses was Gloria Tibi Trinitas, from which the style of instrumental polyphonic music, called In nominee, was born. All English Renaissance composers we mentioned above, and even the early Baroque composers up to Henry Purcell, wrote in this style. Here it is, performed by the Tallis Scholars, Peter Phillips directing. The picture above, taken from a "partbook" (a book of sheet music), containing Missa Gloria Tibi Trinitas, may be the likeness of John Taverner.

one. On the other hand, many composers followed Taverner: Thomas Tallis, 15 years his junior, William Byrd (born around 1540), then Thomas Morley (1557), John Dowland and John Bull, both born around 1563, and many more. Taverner lived and worked during the reign of Henry VIII and the English Reformation and, as a religious composer, was strongly affected by changes that the Church of England underwent during that period. In 1526 Taverner went to Oxford to become the master of choir of the Christ Church College, then called Cardinal College, which had been recently organized by Cardinal Wolsey. Wolsey, for a time a highly influential advisor to the King, became a major patron; in one episode he saved Taverner from accusations of concealing “heretical books,” noting that Taverner was "but a musician." Wolsey fell into disfavor with the King and died in 1530 while on trial. Taverner left Oxford the same year. Later he was hired by Thomas Cromwell, the chief minister to King Henry and one of the major leaders of the Reformation. With Cromwell he took part in the dissolution of the monasteries; it seems that at that time he stopped composing altogether, so practically all the music he wrote was Catholic and pre-Reformation. Taverner wrote eight Masses, several Magnificats, and a large number of motets. One of his most important masses was Gloria Tibi Trinitas, from which the style of instrumental polyphonic music, called In nominee, was born. All English Renaissance composers we mentioned above, and even the early Baroque composers up to Henry Purcell, wrote in this style. Here it is, performed by the Tallis Scholars, Peter Phillips directing. The picture above, taken from a "partbook" (a book of sheet music), containing Missa Gloria Tibi Trinitas, may be the likeness of John Taverner.

The English composer Sir John Tavener died recently, on November 12, 2013. He always claimed to be a direct descendant of John Taverner, even though their names were spelled slightly differently. Tavener was an unusual composer in that he wrote mostly religious music, and an unusual person: an Englishman who converted to Orthodox Christianity. Tavener was born in London on January 28th, 1944. When he was 12, he heard Stravinsky’s Canticum Sacrum, which, as he later said, “made me want to be a composer.” In 1968 Tavener wrote a cantata The Whale, based on the story of Jonah; it was widely noted. The Celtic Requiem was written in 1970. Benjamin Britten thought of it highly enough to persuade the Covent Garden to commission Tavener an opera (Thérèse was staged only in 1979 and was not very successful). In 1977 he wrote another opera, A Gentle Spirit, based on a story by Dostoevsky. The libretto was written by the Irish playwright Gerard McLarnon, a convert to Russian Orthodox Christianity. That same year Tavener also became a convert. Subsequently, Tavener wrote a number of pieces based on Orthodox Christian writings and Russian literature. The Protecting Veil (1988) for cello and strings, was suggested and popularized by the cellist Steven Isserlis. His Song for Athene was set to a text written by a Russian Orthodox abbess. It became very popular after it was performed during Princess Diana’s funeral in 1997. You can listen to it here, performed by the King's College Choir, Cambridge, Stephen Cleobury conducting.Permalink

Christianity. Tavener was born in London on January 28th, 1944. When he was 12, he heard Stravinsky’s Canticum Sacrum, which, as he later said, “made me want to be a composer.” In 1968 Tavener wrote a cantata The Whale, based on the story of Jonah; it was widely noted. The Celtic Requiem was written in 1970. Benjamin Britten thought of it highly enough to persuade the Covent Garden to commission Tavener an opera (Thérèse was staged only in 1979 and was not very successful). In 1977 he wrote another opera, A Gentle Spirit, based on a story by Dostoevsky. The libretto was written by the Irish playwright Gerard McLarnon, a convert to Russian Orthodox Christianity. That same year Tavener also became a convert. Subsequently, Tavener wrote a number of pieces based on Orthodox Christian writings and Russian literature. The Protecting Veil (1988) for cello and strings, was suggested and popularized by the cellist Steven Isserlis. His Song for Athene was set to a text written by a Russian Orthodox abbess. It became very popular after it was performed during Princess Diana’s funeral in 1997. You can listen to it here, performed by the King's College Choir, Cambridge, Stephen Cleobury conducting.Permalink

January 6, 2014. Francis Poulenc. The first several days of the year are rich in composers’ birthdays: three Russians (Mily Balakirev, Nikolai Medtner, and Alexander Scriabin), two Italians (Giovanni Battista Pergolesi and Giuseppe Sammartini, not to be confused with the more famous brother, Giovanni). Josef Suk, the Czech composer, the favorite pupil and son in law of Antonin Dvořák, was also born during the first week of the year, aswas the German composer, Max Bruch. A veritable constellation of smaller stars.

aswas the German composer, Max Bruch. A veritable constellation of smaller stars.

Francis Poulenc was also born in the first week of the year, on January 7, 1899 in Paris. He was brought up comfortably: his father Emil was a director of Poulenc Frères, a pharmaceutical company, which later became the much larger Rhône-Poulenc. When he was 15, Francis started piano lessons with Ricardo Viñes, a friend of Maurice Ravel’s (Viñes premiered many of Ravel’s piano compositions; he also championed the music of Claude Debussy, de Falla and Albéniz). A year later Poulenc was introduced to a group of avant-garde surrealist poets – Max Jacob (the oldest of them and Picasso’s best friend), Guillaume Apollinaire, Paul Éluard and Louis Aragon (some years later Éluard and Aragon would break up with the surrealists and join the French Communist Party). Poulenc started composing seriously around 1917 and in the next three years wrote a number of sonatas (for two clarinets, for piano four hands, for the violin) and songs, some on poems of Apollinaire. In 1920 he got involved with a group of young composers, all of them living on Montparnasse. The music critic Henry Collet called them Les Six. Jean Cocteau was to an extent the organizer, and Eric Satie was the musical leader. In addition to Poulenc, the group included Georges Auric, Louis Durey (probably the least interesting of them all), Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, and Germaine Tailleferre, the only woman in the company. These particular musicians, while all good friends, were never formally organized, but the name stuck.

Probably the most significant piece Poulenc wrote in the period before the Second World War was his Concerto for Two Pianos. He premiered it, together with his friend the pianist Jacques Février, in 1932. Being openly gay, (in 1928 he dedicated his Concert champêtre for harpsichord and orchestra to a lover, the painter Richard Chanlaire), Poulenc proposed a marriage of convenience to a childhood friend, Raymonde Linossier. She refused but they remained good friends. In 1930 Linossier died and Poulenc fell into a depression. Six years later, in 1936 Pierre-Octave Ferroud, a composer and an acquaintance, also died, in a horrible road accident. His death deeply affected Poulenc. He went to the shrine of the Black Virgin in Rocamadour (the statue, made of black wood, is one of the most revered religious objects in France). There he had an epiphany of sorts, which affected him personally, and also influenced his compositional style. He started writing liturgical and religious pieces, something he had never done before: Litanies à la vierge noire were composed right after the visit in 1936; then, a year later, a Mass; later, in 1941, Exultate Deo, then Stabat Mater in1950 and many more.

Poulenc was active during the War, writing many songs and some incidental music. He also wrote a ballet, Les animaux modèles, staged by Serge Lifar at the Paris Opera. After the war he wrote two very important operas, Dialogues des carmélites in1956 and La voix humaine based on a play by Jean Cocteau, for a single voice, two years later. Poulenc died on January 30th of 1963.

Here’s his earlier piece, the already-mentioned Concerto for Two Pianos. It’s a 1962 recording, with Francis Poulenc and his friend, Jacques Février, the same pianists who had performed the Concerto during the premier 30 years earlier. Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire (it became Orchestre de Paris in 1967) is conducted by Pierre Dervaux.

PermalinkDecember 30, 2013. End of 2013. Throughout the year we wrote about composers whose birth dates were lost in subsequent centuries. Most of them came from the early Renaissance period: by the time of the Baroque record keeping had greatly improved. We’d like to finish 2013 with a mention of two more composers who, if not very well known today, have greatly affected the course of musical history.

with a mention of two more composers who, if not very well known today, have greatly affected the course of musical history.

Gilles Binchois was born around 1400 in the city of Mons, which is now in Belgium and back then was the capital of the County of Hainaut. It later became part of the Duchy of Burgundy. During the Hundred Years’ War the Burgundians fought on the side of the English, and at some point even captured Paris. It’s known that around 1425 Binchois was in Paris serving William de la Pole, earl of Suffolk and one of the English commanders during the War. Around 1430 Binchois joined the court chapel of Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy and stayed there for many years. Philip loved the music and in addition to Binchois hired another famous composer, Guillaume Dufay. Philip didn’t have a permanent capital and moved his court between the palaces in Brussels, Bruges, Dijon and other cities of the Duchy; Binchois most likely traveled with the court. Eventually he retired to Soignies, just outside of Mons. He died in 1460. Binchois was considered the finest melodist of the 15th century, although some might argue that this honor belongs to John Dunstaple, and was, with Guillaume Dufay, the most significant composer of the early Burgundian (Franco-Flemish) School.

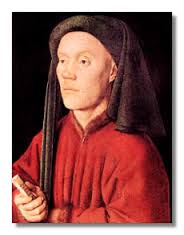

Here is his song (rondeau) Dueil angoisseux, or Anguished grief. For the text Binchois used a poem by Christine de Pizan, an Italian poet (she was born in Venice in 1365) who mostly worked in the courts of the French and Burgundian dukes. It’s performed by the eponymous ensemble, Ensemble Gilles Binchois. And here is another chanson, Triste plaisir et douloureuse joye (Sad pleasure and sorrowful joy). The Swedish mezzo/contralto Lena Susanne Norin is accompanied by Randall Cook on viola da gamba with Susanne Ansorg playing rebec, a predecessor of the violin. The portrait of a man, above left, was painted in 1432 by the most famous Netherlandish painter of the time, Jan van Eyck. Like Guillaume Dufay and Binchois, he also served in the court of Philip the Good. The German art historian Erwin Panofsky believed that this could’ve been a portrait of Gilles Binchois.

A century and a half later, another representative of the Franco-Flemish school ruled the musical world. His name was Orlando di Lasso. Like Binchois, Orlando was also born in Mons, probably in 1532. Orlando spent many years in Italy and, with his work, influenced the music in that country and elsewhere in Europe. We’ll dedicate a separate entry to this talented and very prolific composer, who wrote more than 2000 pieces, from the madrigals and chansons to motets, masses and magnificats. For now, we’ll just present a song of a particular type called villanelle, which consists of 19 lines: five tercets and a quatrain. This one, called Matona, mia cara (My dear lady, I’d love to sing a song below your window), depicts a bawdy German lancer and is set to a text that it too risqué to be reproduced on these pages. But the music is absolutely charming. Listen to it in the performance by the Douglas Frank Chorale. The Madonna and Child Enthroned with Music-Making Angels is by Giovanni Boccati, an Italian painter from Camerino in the Marche, and was painted in 1455.

We’ll dedicate a separate entry to this talented and very prolific composer, who wrote more than 2000 pieces, from the madrigals and chansons to motets, masses and magnificats. For now, we’ll just present a song of a particular type called villanelle, which consists of 19 lines: five tercets and a quatrain. This one, called Matona, mia cara (My dear lady, I’d love to sing a song below your window), depicts a bawdy German lancer and is set to a text that it too risqué to be reproduced on these pages. But the music is absolutely charming. Listen to it in the performance by the Douglas Frank Chorale. The Madonna and Child Enthroned with Music-Making Angels is by Giovanni Boccati, an Italian painter from Camerino in the Marche, and was painted in 1455.

Happy New Year!Permalink

December 23, 2013. Christmas of 2013. We at Classical Connect wish all our listeners a very merry Christmas! As became a tradition, we celebrate Christmas with Bach’s Christmas Oratorio. Here are movements 2 through 4 of Part I: For the First Day of Christmas. The Evangelist, whose role is to read from the Bible,.jpg) narrates from Luke 2:1 “And it came to pass in those days, that there went out a decree from Caesar Augustus, that all the world should be taxed.” It’s followed by the Alto recitative “Now shall my beloved bridegroom” and then the wonderful aria “Prepare thyself, Zion.” The Evangelist is the German tenor Christoph Genz, the Alto – Argentinean mezzo-soprano Bernarda Fink. John Eliot Gardiner conducts the English Baroque Soloists and Monteverdi Choir. The Nativity scene at the left is by Fra Angelico, from a cell of the monastery of San Marco in Florence. It was painted around 1440-41, almost 300 years before Bach composed the Oratorio.

narrates from Luke 2:1 “And it came to pass in those days, that there went out a decree from Caesar Augustus, that all the world should be taxed.” It’s followed by the Alto recitative “Now shall my beloved bridegroom” and then the wonderful aria “Prepare thyself, Zion.” The Evangelist is the German tenor Christoph Genz, the Alto – Argentinean mezzo-soprano Bernarda Fink. John Eliot Gardiner conducts the English Baroque Soloists and Monteverdi Choir. The Nativity scene at the left is by Fra Angelico, from a cell of the monastery of San Marco in Florence. It was painted around 1440-41, almost 300 years before Bach composed the Oratorio.

We also want to mark the birthday of Orlando Gibbons, an English composer baptized on 25 December 25th, 1583. He was one of the last Renaissance English composers, following in the steps on John Dunstaple, JohnTaverner, Thomas Tallis, William Byrd, John Dowland, and many other composers of that great national school. What followed shortly after was the dawn of the baroque era that in England culminated in the art of Henry Purcell and Georg Frideric Handel. Gibbons was born in Oxford into a musical family: his father William was one of the waits in Cambridge (waits were town pipers whose duties included playing loud music to wake townsfolk in the morning; they also participated in processions and greeted the visiting royalty). Four of William’s sons were musicians. At the age of 21 Orlando was made the organist at Chapel Royal. He was also a virtuoso performer on the virginal, a type of harpsichord popular at the time both in England and elsewhere in Europe. In England the “Virginalist school” came into being at the end of the 16th - beginning of the 17th century; at about the same time Girolamo Frescobaldi in Italy and Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck in the Netherlands created many works for that instrument.

in England and elsewhere in Europe. In England the “Virginalist school” came into being at the end of the 16th - beginning of the 17th century; at about the same time Girolamo Frescobaldi in Italy and Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck in the Netherlands created many works for that instrument.

Gibbons, a prolific composer, wrote a number of motets and so-called "anthems," in which a solo voice alternated with the full choir, while the organ provides the accompaniment. One of the most famous is This is the record of John (John is the title refers to John the Baptist). Here it is performed by Robin Blaze, Countertenor, Winchester Cathedral Choir, with Sarah Baldock on the organ; David Hill is conducting. Very popular at the time was his short madrigal The silver swan, performed here by the Rose Consort of Viols with the vocal ensemble Red Byrd. And here is Gibbons’s "Lord of Salisbury" Pavan and Galliard. It’s performed on a modern piano by Glenn Gould. Gibbons was one of Gould’s favorite composers (another, of course, was Johann Sebastian Bach).

PermalinkDecember 16, 2013. Ludwig van Beethoven was born on this day in 1770 in Bonn, or at least we presume he was: the only existing record is that of his baptism, which happened on December 17th. We wrote about Beethoven many times (here, for example), so we’ll just continue the traversal of his piano sonatas, this time sonatas nos. 2 and 3, Op. 2. Both are dedicated to Franz Joseph Haydn. Beethoven met Haydn in the summer of 1792 in Bonn. In November of the same year he moved to Vienna to study with the great composer. A piano child prodigy, at the age of 21 he was already well know as an incomparable piano improviser. Even though he was composing from the age of 13 and by the time of his arrival in Vienna had written a number of pieces, Beethoven understood that as composer he had many technical shortcomings and needed to study. In addition to taking composition lessons with Haydn, he studied counterpoint with Johann Georg Albrechtsberger, the organist at the St-Stephen’s cathedral, as well as the violin with a friend, the violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh. He also worked with the composer Antonio Salieri. In Vienna Beethoven established himself as a piano virtuoso, performing in private salons. He often played preludes and fugues from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier. He continued to compose, both on the large and small scale but without presenting or publishing most of his music. When he was just 13, while still in Bonn, he composed a piece that is known as his "Concerto no. 0." He wrote down the piano part but didn’t complete the orchestral score, so when the concerto was performed, the rest of the orchestral part had to be arranged on the fly. This concerto is practically never performed these days. Also around that time he wrote several piano sonatas, strongly influenced by the style of the Mannheim school, with sudden bursts of forte and unexpected pianos (we wrote about Carl Stamitz, probably the most interesting representative of this school, here). Then, between 1787 and 1789 he wrote the large sections of yet another piano concerto, which he completed in Vienna in 1795. We know it as his Concerto no. 2. There is confusion surrounding his first two "official" piano concertos: their numbers come not from the sequence in which they were composed but in which they were published. The concerto known as number 1 was actually composed in 1796-97; both concertos were published years later, Concerto no. 1 first, as opus 15 and then Concerto no. 2 as opus 19. In 1795, in a “coming of age” concert, Beethoven’s first public appearance in Vienna, he played his own composition, piano concerto no. 2. Soon after he published his first officially numbered composition, a set of piano trios, Op. 1. Three piano sonatas followed, his opus 2.

example), so we’ll just continue the traversal of his piano sonatas, this time sonatas nos. 2 and 3, Op. 2. Both are dedicated to Franz Joseph Haydn. Beethoven met Haydn in the summer of 1792 in Bonn. In November of the same year he moved to Vienna to study with the great composer. A piano child prodigy, at the age of 21 he was already well know as an incomparable piano improviser. Even though he was composing from the age of 13 and by the time of his arrival in Vienna had written a number of pieces, Beethoven understood that as composer he had many technical shortcomings and needed to study. In addition to taking composition lessons with Haydn, he studied counterpoint with Johann Georg Albrechtsberger, the organist at the St-Stephen’s cathedral, as well as the violin with a friend, the violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh. He also worked with the composer Antonio Salieri. In Vienna Beethoven established himself as a piano virtuoso, performing in private salons. He often played preludes and fugues from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier. He continued to compose, both on the large and small scale but without presenting or publishing most of his music. When he was just 13, while still in Bonn, he composed a piece that is known as his "Concerto no. 0." He wrote down the piano part but didn’t complete the orchestral score, so when the concerto was performed, the rest of the orchestral part had to be arranged on the fly. This concerto is practically never performed these days. Also around that time he wrote several piano sonatas, strongly influenced by the style of the Mannheim school, with sudden bursts of forte and unexpected pianos (we wrote about Carl Stamitz, probably the most interesting representative of this school, here). Then, between 1787 and 1789 he wrote the large sections of yet another piano concerto, which he completed in Vienna in 1795. We know it as his Concerto no. 2. There is confusion surrounding his first two "official" piano concertos: their numbers come not from the sequence in which they were composed but in which they were published. The concerto known as number 1 was actually composed in 1796-97; both concertos were published years later, Concerto no. 1 first, as opus 15 and then Concerto no. 2 as opus 19. In 1795, in a “coming of age” concert, Beethoven’s first public appearance in Vienna, he played his own composition, piano concerto no. 2. Soon after he published his first officially numbered composition, a set of piano trios, Op. 1. Three piano sonatas followed, his opus 2.

The second of these sonatas, no 2 in A Major, consists of four movements: Allegro vivace; Largo appassionato; Scherzo: Allegretto; and Rondo: Grazioso. Karl Hass, whose Adventures in Good Music was the most listened to classical music program ever produced, used the touching Largo appassionato as the musical theme (Mr. Haas’s 100th birthday was just 10 days ago, on December 6th: he was born on that day in 1913 in Speyer, Germany). You can hear Sonata op.2 no. 2 in the performance by Emil Gilels. The 3rd sonata, which followed shortly after, in C Major, is usually the longest of the three (it runs for about 25 minutes, although Gilels manages to stretch sonata no. 2 to the same length) and technically the most difficult. It also has four movements: Allegro con brio, Adagio, Scherzo: Allegro, and Allegro assai. You can hear it in the performance by Richard Goode. Both sonatas are immediately recognizable as Beethoven’s, even if they lack the depth he developed later in his career. With their surprising and unpredictable outbursts, as for example in the slow movement of the 3rd sonata, they owe more to the Mannheim school than to the dedicatee, Haydn, or Beethoven’s idol, Mozart.

Permalink