Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

June 16, 2014. Igor Stravinsky was born on June 17th, 1882, in Oranienbaum, outside of Saint Petersburg. We celebrate his birthday every year (for example, here and here): he was one of the most influential composers of the 20th century and so multi-faceted that during his life he managed to affect several very different styles in the development of classical music. From the orchestral opulence, new sounds and rhythms of his Russian period, to the exquisite neoclassical reserve that followed, to the serialism of his later years – each of these periods didn’t just produce great masterpieces, they produced music that affected generations of composers.

the 20th century and so multi-faceted that during his life he managed to affect several very different styles in the development of classical music. From the orchestral opulence, new sounds and rhythms of his Russian period, to the exquisite neoclassical reserve that followed, to the serialism of his later years – each of these periods didn’t just produce great masterpieces, they produced music that affected generations of composers.

Stravinsky turned to neoclassicism around 1920 (he actually didn’t like the term and thought it to be rather meaningless). Neoclassicism was to a large extent a reaction to the late Romantic, programmatic music, an attempt to revert to the earlier, Baroque or even pre-Baroque sensibilities. Stravinsky was not the first one to write in this style: Richard Strauss’s Le bourgeois gentilhomme Op. 60, which was written in 1911, and especially Prokofiev’s Symphony no. 1, composed in 1917, could be considered the precursors. But for Strauss and Prokofiev these were interesting but fleeting experiments without much of a follow-up. It was Stravinsky who molded this approach into a much more consistent paradigm. It’s interesting that around the same time another artist who also worked in many different styles, the supremely talented Picasso, also entered into his neoclassical phase, together with many Italian artists who in the following years unfortunately veered toward fascism.

One of Stravinsky’s first neoclassical pieces was Pulcinella, which was also his first ballet created for Diagilev’s Ballets Russes since the Rite of Spring seven years earlier. Diagilev wanted to stage a ballet based on the Italian Commedia del’Arte. Commedia developed in Italy as early as the 17th century, as an improvisational theatrical performance, with a set of stock characters. They were the roguish Arlecchino; his sidekick Brighella; Pantalone, a rich merchant; Pulcinella, who chased pretty girls; Pierrot and Pierrette, and many others. Diagilev, very much a co-creator of his ballets, also wanted to use several old tunes; at the time they were attributed to Pergolesi but it turned out later that they might have been written by other composer. Ernest Ansermet, the Ballets Russes’ chief conductor, wrote to Stravinsky about Pergolesi, a 17th century Italian with a tragically short life who wrote several comic operas. Stravinsky, not too familiar with Pergolesi’s music, had to study the scores. He borrowed several themes, adopted the pseudo-Baroque mannerisms and tempos, and used them to create something new and highly original. The one-act ballet was scored for a chamber orchestra and three singers; it premiered in the Paris Opera on May 15, 1920, Ernest Ansermet conducting. The set designs were by Picasso. Some years later Stravinsky created an orchestral suite based on the ballet with no singing parts. He also wrote two different Suites Italienne based on the same music, one for the cello and piano, in collaboration with Gregor Piatigorsy, and another for the violin and piano that he worked on with Samuel Dushkin. (Dushkin and Stravisnky had also worked together on the Violin concerto, which Dushkin premiered in 1931). We have both of the instrumental versions in our library: here’s the one for the cello performed by Alexei Romanenko with Christine Yoshikawa on the piano; and here’s the one for the violin, with Janet Sung and Robert Koenig. But what we’d like to hear today is the original version of the ballet, the one for the orchestra with singers. This, in particular, is an interesting performance from a historical perspective: the conductor in the 1965 recording is the same Ernest Ansermet, 45 years after the premier (at the time of the recording he was 82 years old). Marilyn Tyler is the soprano, Carlo Franzini the tenor, Boris Carmeli the baritone. The orchestra is L'Orchestre de la Suisse Romande. To listen, click hear. The photo of Stravisnky, above, was made one year after the premier of Pulcinella, in 1921.

PermalinkJune 9, 2014. Richard Strauss at 150 and Edvard Grieg. Richard Strauss was born this week, on June 11th of 1864. At the end of his life, in 1947 (he died two years later) he declared: "I may not be a first-rate composer, but I am a first-class second-rate composer." It might have seemed that way in the middle of the 20th century. Strauss’ music, much of it in the late-romantic German tradition, sounded dated compared, for example, to Stravinsky or Schoenberg. But these days Strauss’s judgment seems too harsh. His music endures and is probably more popular these days than it was at the time of his death. Strauss worked in many different genres. He wrote large tone poems (Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, and Don Quixote, written in the years from 1895 to 1897, are the most popular), concertos (for the violin early in his career, in 1881, and a famous one for the oboe, at the end of it, in 1945). He wrote a not very successful and long Burleske for piano and orchestra, practically a one-movement piano concerto. He also wrote a number of wonderful songs. But it’s probably his operas that have maintained Strauss’s reputation throughout the last several decades. His first successful opera was the 1905 Salome, based on a play by Oscar Wilde (not everybody was impressed: Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, after suffering through the opera, went to Café de la Paix next door and, according to Chaliapin, became literally sick). The difficult and musically even more daring Elektra came four years later. But it was his next opera,Der Rosenkavalier, that brought him the greatest success. Very well received at its premier in 1911, it has remained in the repertoire of all major opera houses till today. Two main characters, the Marschallin (soprano) and her young lover Octavian (a mezzo trouser role) had an illustrious history. One of the most famous Marschallins was the great German soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf. Régine Crespin and Christa Ludwig were also very successful in this role. At the end of the 20th century Kiri Te Kanawa owned the role, and lately it has practically belonged to Renée Fleming. Christa Ludwig, naturally a mezzo, also sung the role of Ottavian. Tatiana Troyanos, Frederica von Stade and Anne Sofie von Otter were great Ottavians. Here’s the 1992 concert recording of the final scene of Der Rosenkavalier. The Marschallin is Renee Fleming, Octavian – Frederica von Stade, and Sophie is sung by Kathleen Battle, all three in great voices. Claudio Abbado leads the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. We cut out about 5 minutes of applause.

compared, for example, to Stravinsky or Schoenberg. But these days Strauss’s judgment seems too harsh. His music endures and is probably more popular these days than it was at the time of his death. Strauss worked in many different genres. He wrote large tone poems (Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, and Don Quixote, written in the years from 1895 to 1897, are the most popular), concertos (for the violin early in his career, in 1881, and a famous one for the oboe, at the end of it, in 1945). He wrote a not very successful and long Burleske for piano and orchestra, practically a one-movement piano concerto. He also wrote a number of wonderful songs. But it’s probably his operas that have maintained Strauss’s reputation throughout the last several decades. His first successful opera was the 1905 Salome, based on a play by Oscar Wilde (not everybody was impressed: Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, after suffering through the opera, went to Café de la Paix next door and, according to Chaliapin, became literally sick). The difficult and musically even more daring Elektra came four years later. But it was his next opera,Der Rosenkavalier, that brought him the greatest success. Very well received at its premier in 1911, it has remained in the repertoire of all major opera houses till today. Two main characters, the Marschallin (soprano) and her young lover Octavian (a mezzo trouser role) had an illustrious history. One of the most famous Marschallins was the great German soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf. Régine Crespin and Christa Ludwig were also very successful in this role. At the end of the 20th century Kiri Te Kanawa owned the role, and lately it has practically belonged to Renée Fleming. Christa Ludwig, naturally a mezzo, also sung the role of Ottavian. Tatiana Troyanos, Frederica von Stade and Anne Sofie von Otter were great Ottavians. Here’s the 1992 concert recording of the final scene of Der Rosenkavalier. The Marschallin is Renee Fleming, Octavian – Frederica von Stade, and Sophie is sung by Kathleen Battle, all three in great voices. Claudio Abbado leads the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. We cut out about 5 minutes of applause.

Edvard Grieg was also born this week, on June 15th of 1843. He put Norway on the musical map of Europe (it’s safe to say that to this day he remains the only Norwegian composer of note). His most popular compositions were the lyrical Piano concerto and the incidental music to Ibsen's play Peer Gynt (Grieg created two suites out of the incidental music, each containing four movements, and this is how it’s usually performed on the concert stage). His Violin sonata no. 3 is played often (we have several recordings in our library, here is one with the violinists Gregory Maytan and Nicole Lee on the piano). In 1882 he wrote a sonata for cello and piano. Grieg, an excellent pianist, played the accompanying piano at the premiere. We’ll hear it in a live recording made in 1964 by an even better pianist, Sviatoslav Richter, and one of the greatest cellists of the 20th century, Mstislav Rostropovich.

PermalinkJune 2, 2014. Schumann and Arcadelt. Robert Schumann was born on June 8th, 1810 in Zwickau, Saxony. We write about him every year, as Schumann remains one of the most important composers in the history of Western music. Last year we wrote about his gift as a songwriter. He wrote fours symphonies and quite a bit of chamber music. Still, he was first and foremost a piano composer. Starting with opus 1, Variations on the name "Abegg," written in 1830, for the following nine years this was the only instrument he wrote for. And it’s for the piano that he wrote his greatest compositions. One of them is Kreisleriana, Op. 16, written in 1838. That was a difficult but at the same time tremendously productive period in Schumann’s life. Robert was carrying on a romantic relationship with Clara Wieck, a daughter of his former piano teacher and a piano prodigy. Robert’s infatuation with Clara dated to 1835, when she was just 15. When Clara reached 18, he formally proposed to her. Wieck-senior refused to consent, as he considered a mere composer not capable of providing for his daughter. They would marry only in 1840. In the mean time Schumann was writing some of his most interesting work: Fantasiestücke, Symphonic Etudes, Fantasie in C major, and Kreisleriana. Many of Schumann’s compositions are based on, or at least have an allusion to, literary sources, and so does Kreisleriana. “Kreisler” in the title is Johannes Kreisler, the protagonist of a novel by the German writer E.T.A. Hoffmann, an eccentric composer of genius (Kreisler appeared in several other Hoffmann novels, including the great The Life and Opinions of the Tomcat Murr). Schumann called Kreisleriana a fantasy for piano and dedicated it to Frédéric Chopin. It consists of eight movements, each in a different mood, like the temperamental, and probably manic-depressive, Kreisler – and of course Schumann himself. In our library we have Kreisleriana in the performances by two young pianists, the German/Russian Elena Melnikova and the Chinese/American Jenny Q Chai. This time we’d like to play it in the performance of a wonderful interpreter of the music of Schumann, the Georgian pianist Eliso Virsaladze. This recording was made in 1965 when Eliso was 23 years old. One year later she received the first prize at the Schumann Competition in Zwickau. These days Ms. Virsaladze is still active as a professor at the Moscow Conservatory. You can listen to it here.

and foremost a piano composer. Starting with opus 1, Variations on the name "Abegg," written in 1830, for the following nine years this was the only instrument he wrote for. And it’s for the piano that he wrote his greatest compositions. One of them is Kreisleriana, Op. 16, written in 1838. That was a difficult but at the same time tremendously productive period in Schumann’s life. Robert was carrying on a romantic relationship with Clara Wieck, a daughter of his former piano teacher and a piano prodigy. Robert’s infatuation with Clara dated to 1835, when she was just 15. When Clara reached 18, he formally proposed to her. Wieck-senior refused to consent, as he considered a mere composer not capable of providing for his daughter. They would marry only in 1840. In the mean time Schumann was writing some of his most interesting work: Fantasiestücke, Symphonic Etudes, Fantasie in C major, and Kreisleriana. Many of Schumann’s compositions are based on, or at least have an allusion to, literary sources, and so does Kreisleriana. “Kreisler” in the title is Johannes Kreisler, the protagonist of a novel by the German writer E.T.A. Hoffmann, an eccentric composer of genius (Kreisler appeared in several other Hoffmann novels, including the great The Life and Opinions of the Tomcat Murr). Schumann called Kreisleriana a fantasy for piano and dedicated it to Frédéric Chopin. It consists of eight movements, each in a different mood, like the temperamental, and probably manic-depressive, Kreisler – and of course Schumann himself. In our library we have Kreisleriana in the performances by two young pianists, the German/Russian Elena Melnikova and the Chinese/American Jenny Q Chai. This time we’d like to play it in the performance of a wonderful interpreter of the music of Schumann, the Georgian pianist Eliso Virsaladze. This recording was made in 1965 when Eliso was 23 years old. One year later she received the first prize at the Schumann Competition in Zwickau. These days Ms. Virsaladze is still active as a professor at the Moscow Conservatory. You can listen to it here.

From a composer who was popular for the last century and a half, and still is, we’d turn to a composer who was also very popular during his lifetime, except that he was practically forgotten for the last three hundred years – Jacob (or Jacques) Arcadelt. Arcadelt was born around 1507. This makes him a contemporary of the English composer Thomas Tallis, the Spaniard Cristóbal de Morales, and another Franco-Flemish composer, Jacob Clemens non Papa. Born in what is now Belgium, he moved to Italy as a young man. He sung in the choir of the St.-Peter’s Basilica and later in the Sistine Chapel, where he worked from about 1530 to 1551. There he met Michelangelo, who was then painting the Last Judgment. Arcadelt, at the time a very popular composer of madrigals, set two poems by Michelangelo to music. Apparently Michelangelo wasn’t impressed. Arcadelt’s music stayed popular even after his death in 1568: in Caravaggio’s Lute Player, painted in 1600, the sheet music is by Arcadelt! (The androgynous singer is probably a castrato). Arcadelt wrote several hundred madrigals and chansons, and also wrote church music – several masses and motets. But it was the “sweet style” of his madrigals that he was famous for. Here’s his chanson Robin Par Bois Et Compagnes ("Robin As He Goes Through The Woods And The Fields") set to a poem by the famous French poet Pierre de Ronsard. It’s performed by the Egidius Kwartet. And here is his madrigal Il bianco e dolce cigno, sung by the Hilliard Ensemble.

Sistine Chapel, where he worked from about 1530 to 1551. There he met Michelangelo, who was then painting the Last Judgment. Arcadelt, at the time a very popular composer of madrigals, set two poems by Michelangelo to music. Apparently Michelangelo wasn’t impressed. Arcadelt’s music stayed popular even after his death in 1568: in Caravaggio’s Lute Player, painted in 1600, the sheet music is by Arcadelt! (The androgynous singer is probably a castrato). Arcadelt wrote several hundred madrigals and chansons, and also wrote church music – several masses and motets. But it was the “sweet style” of his madrigals that he was famous for. Here’s his chanson Robin Par Bois Et Compagnes ("Robin As He Goes Through The Woods And The Fields") set to a poem by the famous French poet Pierre de Ronsard. It’s performed by the Egidius Kwartet. And here is his madrigal Il bianco e dolce cigno, sung by the Hilliard Ensemble.

PermalinkMay 26, 2014. Albeniz, Marais, Elgar. And also Korngold, and Glinka – all were born this week, but we just don’t have enough space to celebrate them all. Isaac Albéniz was born on May 29th, 1860. A wonderful composer, the oldest of the trio that transformed Spanish classical music at the end of the 19th century, he wrote mostly for the piano and guitar. His music got more and more interesting toward the end of his short life – he composed his masterpiece, Iberia, between 1905 and 1909, and died that year, 10 days short of his 49th birthday We wrote about him extensively before (for example, here and here), so this time we’ll just play one of the pieces from Book I of Iberia, Fête-dieu à Seville, which is sometimes called “El Corpus Christi en Sevilla.” It depicts, so to speak, a Catholic procession celebrating the real presence of body and blood of Jesus Christ. Fête-dieu is performed by the great Spanish pianist Alicia de Larrocha. The cubist picture of the feast is by the Portugese artist Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso. It was painted in 1913.

Catholic procession celebrating the real presence of body and blood of Jesus Christ. Fête-dieu is performed by the great Spanish pianist Alicia de Larrocha. The cubist picture of the feast is by the Portugese artist Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso. It was painted in 1913.

Marin Marais was born on May 31st, 1656 in Paris. He became better known since the release of the French film Tous les matins du monde (All the Mornings of the World) in 1991, than at any time since his death in 1728. Marais studied composition with Jean-Baptiste Lully and the bass viol with the composer and viol virtuoso Monsieur de Sainte-Colombe, the subject of Tous les matins. In 1685 Marais was appointed Ordinaire de la Musique de la Chambre du Roi, a member of King Louis XIV’s private orchestra. He stayed in that position for many years, serving Louis XV after the Sun King’s death. Most of his work was for the viol (viola-da-gamba): between 1686 and 1725 Marais wrote five books of music, around 550 pieces altogether. He also wrote several operas but those are rarely performed these days. Here’s a late composition, Sonnerie de Ste. Geneviève du Mont-de-Paris (The Bells of St. Genevieve); it was written in 1723. Jordi Savall, probably the most famous viola da gamba player of late, is supported by Fabio Biondi on the violin and Pierre Hantaï on the harpsichord. And here is Marais’s rendition of the famous La Folia or Les folies d'Espagne. Again, Jordi Savall on viola da gamba, this time with Anne Gallet on the harpsichord and Hopkinson Smith on theorbo, a type of a lute.

Are we terribly amiss if we value the compositional talents of Edward Elgar not quite as highly as the British public seems to do? Yes, the Pomp and Circumstance Marches are arousing and, in parts, unexpectedly witty. The Enigma Variations, if perhaps not as enigmatic as the title would suggest, are very well crafted. And the Cello concerto, especially when performed by Jacquelinedu Pré, is wonderful. But one has to consider that Elgar’s active career covered the last decade of the 19th and the first two decades of the 20th centuries, a time of revolutionary changes in classical music, and in that perspective his contributions may appear somewhat limited. Elgar was born on June 2nd, 1857 in a small village outside of Worcester in the West Midlands, England. His father had a music shop and tuned pianos. Elgar was mostly self-taught, studying music in his father’s shop. He started composing at the age of 20, but it was not till 1890s that his work became noticed. In 1899 he wrote the Variations on an Original Theme for Orchestra ("Enigma"), Op. 36, commonly called Enigma Variations. It consists of a theme and 14 variations. Each variation is dedicated to a friend or, in the case of the first variation, his wife. Variation IX, dedicated to August Jaeger, a music publisher and close friend, was subtitled “Nimrod” (Jaeger is hunter in German, and the Biblical Nimrod was "a mighty hunter before the Lord"). This variation became especially popular, and for a good reason: it’s one of the best pieces of music ever written by Elgar. We can hear all Variations in the performance by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Andrew Litton conducting.

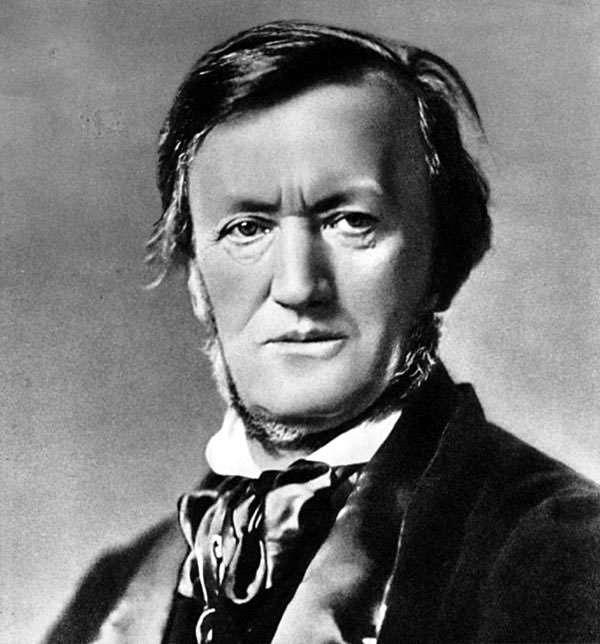

PermalinkMay 19, 2014. Richard Wagner. The great German opera composer was born this week on May 22nd of 1813. We wrote about his early operas, and last year on his 200th birthday, about his whole life, in more detail. This time we’ll look into some of the operas of his mature period. In 1849 Wagner had to escape Germany after an uprising in Dresden in 1849 – Wagner was known as a supporter of socialists and anarchists and was at risk of being arrested. He went to Paris and then Switzerland, settling in Zurich. He maintained a close relationship with Franz Liszt, a friend and eventually his father-in-law, but otherwise felt quite isolated. In the early years of the exile he didn’t write much music, instead concentrating on articles and essays. Among them was the notorious “Judaism in Music,” his first openly anti-Semitic opus. In it Wagner attacked Jews in general (snobbishly, for not being able to speak proper European languages and also for their purported commercialism) and composers Mendelssohn and Meyerbeer in particular. At the time the essay was practically ignored, though the pianist and composer Ignaz Moscheles did object in a letter to the publishers. In the 1960s, though, in the aftermath of WWII and the Holocaust, it became the subject of a heated debate. It’s interesting to note that as so many anti-Semites, Wagner had quite a number of Jewish friends.

Dresden in 1849 – Wagner was known as a supporter of socialists and anarchists and was at risk of being arrested. He went to Paris and then Switzerland, settling in Zurich. He maintained a close relationship with Franz Liszt, a friend and eventually his father-in-law, but otherwise felt quite isolated. In the early years of the exile he didn’t write much music, instead concentrating on articles and essays. Among them was the notorious “Judaism in Music,” his first openly anti-Semitic opus. In it Wagner attacked Jews in general (snobbishly, for not being able to speak proper European languages and also for their purported commercialism) and composers Mendelssohn and Meyerbeer in particular. At the time the essay was practically ignored, though the pianist and composer Ignaz Moscheles did object in a letter to the publishers. In the 1960s, though, in the aftermath of WWII and the Holocaust, it became the subject of a heated debate. It’s interesting to note that as so many anti-Semites, Wagner had quite a number of Jewish friends.

During that time Wagner also wrote an important essay titled “Opera and Drama,” in which he described and promoted his idea of musical drama. While laying out the theoretical basis of his future work (all his “musical dramas” were still yet to be written), he disavowed his earlier operas, even the very successful Rienzi, Tannhäuser and Lohengrin, as old-fashioned and “non-dramatic.” In “Opera and Drama” he talked about the importance of poetry as the engine of the overall dramatic experience, in theory even superseding the music (he changed his opinion later on, after reading a Schopenhauer description of music as supreme art), and, for the first time, described the role of musical motifs associated with specific persons, places or events. The use of these "leitmotifs" in his later operas became a trademark.

All along Wagner was working on the librettos for the operas Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung). He had written an episode called Siegfried's Death while still in Dresden in 1848, and in Zurich continued writing and revising different episodes that would become a four-opera cycle: Das Rheingold (The Rhine Gold), Die Walküre (The Valkyrie), Siegfried, and Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods). By 1852 he was done with the writing. Another year had passed till he started composing. Das Rheingold came first, in 1853 and ’54, then Die Walküre. He completed the first two operas by 1856. He started working on Siegfried, but set it aside. The reason was his developing infatuation with one Mathilde Wesendonck. Mathilde was the wife of Wagner’s patron, Otto Wesendonck, a rich local merchant. Wesendonck, a music lover and an admirer of Wagner, became his major patron, paying for his expenses and even giving him a cottage to live and work in. Musically, Wagner’s infatuation resulted first in the Wesendonck Lieder, five songs set to the poems by Mathilde (here’s "Im Treibhaus" ("In the greenhouse"), from Wesendonck Lieder, performed by the soprano Rebecca Wascoe with Jeffrey Peterson on the piano). The listener may recognize music from the prelude of Act III of Tristan und Isolde: Wagner just started working on Tristan, a tragic love story set during the Arthurian times. It’s not clear if Mathilde ever responded to Wagner’s entreaties, but one of Richard’s love letters was intercepted by his wife, Minna. A scandal ensued, Minna left for Dresden, and Wagner went to Venice, alone. He continued working on Tristan and completed it in 1859. Extremely influential (dozens of major composer, from Debussy to Mahler, were affected by it), Tristan is considered the pinnacle of Wagner’s art. Here’s Wilhelm Furtwängler conducting the Philharmonia Orchestra in the Prelude from Act 3 of Tristan und Isolde. The recording was made in 1952.

PermalinkMay 12, 2014. Massenet and Fauré. Jules Massenet was born on this day in 1842 in Saint-Étienne, France. The family moved to Paris when Jules was six. At the age of 11 he entered the Paris Conservatory (admission age was as low as nine). One of his teachers there was the composer Ambroise Thomas; they continued a relationship even after Massenet’s graduation. In 1862 he won the coveted Prix de Rome and went to study in Rome for three years. Massenet wrote his first opera, La grand' tante, in 1866 (it was staged a year later in Opéra-Comique) but it was not till 1884 that he met real success. That year he wrote Manon, the opera based on Abbé Prévost’s novel about the chevalier des Grieux and his lightheaded lover, Manon Lescaut. The opera was staged at the same Opéra-Comique in January of 1884. It immediately became very popular and a staple of the Opéra-Comique’s repertoire, with thousands of performances in the following years. Its fame spread around Europe and South America. Victoria de los Ángeles, Anna Moffo, Beverly Sills were among the famous Manons, Enrico Caruso and Beniamino Gigli sung the role of des Grieux. Eight years later, in 1892, Massenet was almost as successful with another opera, Werther. Massenet wrote 25 operas in all, but only one other, Thais, approached the level he had reached in Manon. Here’s a duet “Tu pleures!...”, the finale of the opera, performed by Ms. Sills as Manon and the great Swedish tenor, Nicolai Gedda as des Grieux. The recording was made in 1970.

of his teachers there was the composer Ambroise Thomas; they continued a relationship even after Massenet’s graduation. In 1862 he won the coveted Prix de Rome and went to study in Rome for three years. Massenet wrote his first opera, La grand' tante, in 1866 (it was staged a year later in Opéra-Comique) but it was not till 1884 that he met real success. That year he wrote Manon, the opera based on Abbé Prévost’s novel about the chevalier des Grieux and his lightheaded lover, Manon Lescaut. The opera was staged at the same Opéra-Comique in January of 1884. It immediately became very popular and a staple of the Opéra-Comique’s repertoire, with thousands of performances in the following years. Its fame spread around Europe and South America. Victoria de los Ángeles, Anna Moffo, Beverly Sills were among the famous Manons, Enrico Caruso and Beniamino Gigli sung the role of des Grieux. Eight years later, in 1892, Massenet was almost as successful with another opera, Werther. Massenet wrote 25 operas in all, but only one other, Thais, approached the level he had reached in Manon. Here’s a duet “Tu pleures!...”, the finale of the opera, performed by Ms. Sills as Manon and the great Swedish tenor, Nicolai Gedda as des Grieux. The recording was made in 1970.

Another French composer, Gabriel Fauré, was born on the same day three years later, in 1845. While Massenet was a conservative composer with a wonderful melodic gift, Fauré was a much more complex figure. In France, he in many ways served as a bridge between the Romanticism of the mid-19th century and 20th century music. His harmonies influenced the “impressionists,” Debussy and Ravel and even composers of subsequent generation. A professor for many years and eventually the head of the Paris Conservatory, he had a large number of pupils and by the time he retired from the Conservatory at the age of 75, he was considered a national institution. Two years later, in 1922, he was celebrated in an event organized by the President of the Republic. But in 1845, when Fauré was born, France was a very different place, both culturally and politically..jpg) Louis-Philippe was the King, Chopin was still alive, Schumann was at the height of his creative powers, and Hector Berlioz reigned on the French music scene. Fauré was born in a small town of Pamiers, in the southwest of France. His family was not musical, but as a boy he loved to play a harmonium in the chapel of his school. When he was nine, his father sent him to Paris, to study in the recently opened École de Musique Classique et Religieuse (School of Classical and Religious Music). He stayed at the school for 11 years. In 1861 Camille Saint-Saëns joined the school as the head of the piano department. Saint-Saëns introduced his students to contemporary music, including that of Wagner (in the Paris Conservatory, which at that time was headed by the opera composer Daniel Auber – who incidentally also wrote an opera called Manon Lescaut – Wagner was practically banned). Fauré became Saint-Saëns’s favorite pupil, and even though the teacher was 10 years older than the student, they became close friends. This friendship lasted for many years, till Saint-Saëns’s death in 1921. In 1866, upon graduating from the School, Fauré accepted a position of the organist in a church at Rennes, the main city of Brittany. Four years later he returned to Paris, not without Saint-Saëns’s help, as an assistant organist at the recently completed Notre-Dame de Clignancourt. At that time he was composing, but not much (and earning even less); it was not till 1880s that his art matured. Here’s his wonderful, Élégie (Elegy) for cello and piano. Written in 1880, it was first performed in 1883. An openly emotional piece, it was one of the last of the kind: very soon Fauré’s style turned more circumspect. We’ll hear it played by the 24 year-old Jacqueline du Pré, with Gerald Moore on the piano.

Louis-Philippe was the King, Chopin was still alive, Schumann was at the height of his creative powers, and Hector Berlioz reigned on the French music scene. Fauré was born in a small town of Pamiers, in the southwest of France. His family was not musical, but as a boy he loved to play a harmonium in the chapel of his school. When he was nine, his father sent him to Paris, to study in the recently opened École de Musique Classique et Religieuse (School of Classical and Religious Music). He stayed at the school for 11 years. In 1861 Camille Saint-Saëns joined the school as the head of the piano department. Saint-Saëns introduced his students to contemporary music, including that of Wagner (in the Paris Conservatory, which at that time was headed by the opera composer Daniel Auber – who incidentally also wrote an opera called Manon Lescaut – Wagner was practically banned). Fauré became Saint-Saëns’s favorite pupil, and even though the teacher was 10 years older than the student, they became close friends. This friendship lasted for many years, till Saint-Saëns’s death in 1921. In 1866, upon graduating from the School, Fauré accepted a position of the organist in a church at Rennes, the main city of Brittany. Four years later he returned to Paris, not without Saint-Saëns’s help, as an assistant organist at the recently completed Notre-Dame de Clignancourt. At that time he was composing, but not much (and earning even less); it was not till 1880s that his art matured. Here’s his wonderful, Élégie (Elegy) for cello and piano. Written in 1880, it was first performed in 1883. An openly emotional piece, it was one of the last of the kind: very soon Fauré’s style turned more circumspect. We’ll hear it played by the 24 year-old Jacqueline du Pré, with Gerald Moore on the piano.

Claudio Monteverdi was also born this week. We’ll try to dedicate an entry to him alone (he fully deserves it) some other time.

Permalink