Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

July 28, 2014. Guillaume Dufay. Around this time of year we celebrate the birthday of Guillaume Dufay, the most influential composer of the early Renaissance. Even though we usually know little about the early life of people who lived in the 14th or 15th centuries, tradition has it that Dufay was born on August 5th, 1397. We wrote about Dufay’s life when we celebrated his birthday a year ago, so this time we’ll write about his place in the European musical canon. This place is unique: Dufay was one of the last Medieval and at the same time one of the first Renaissance composers. The music of the medieval period centered in Northern France, in Avignon, where seven popes (and several anti-popes) lived during the 14th century, and in Italy. The first significant polyphonic music was written during that time. Guillaume de Machaut was the most famous poet and composer of the period; he lived in Reims and worked in its famous cathedral, the crowning place of the French kings. It was a time of tremendous upheavals. The Hundred years’ war, which started in 1337 and lasted till 1453, devastated France (Reims, for example, fell to the English in 1370 and was liberated by Joan of Arc only in 1429). All the while Burgundy, a war ally of England, prospered. Through marriage or war, Burgundians expanded their territory, acquiring Flanders, Brabant, and many smaller principalities. These were the circumstances under which the cultural center of northern Europe shifted from France to Burgundy. The dukes, all of them patrons of arts (and often active practitioners), didn’t maintain one court, as did the French and English kings: Dijon was their administrative capital, but the court moved around the country, staying in Brussels, Bruges, Arras and other northern cities more often than in Dijon. Court musicians moved with the dukes, and many of these places were the court stayed became centers of music making. Dufay was the elder, and most revered, composer in a group that also included John Dunstaple, Gilles Binchois and Antoine Busnois. These were the first of what we now call Renaissance musicians. They introduced new esthetic sensibilities, which during the following two hundred years led to the development of an incredibly rich musical culture. The roots of the music of Palestrina, Orlando di Lasso, the Gabrielis and William Bird, which so often appears quite modern even to our ear, all go back to Dufay and the Burgundians. Not that Dufay was a completely modern composer. For him music was not only about the sound, the melody, or the aural interaction of voices in a polyphonic piece. It was also an intellectual game, in which a theme hidden from the listener could be valued for the pattern it creates on a sheet of music. But these were the vestiges of medieval music, famous for its complex arrangements, often more mathematical than esthetic. What his contemporaries valued the most were his melodic gifts, the beautiful polyphony of his masses, and the lively and graceful rhythms of some of his chansons.

people who lived in the 14th or 15th centuries, tradition has it that Dufay was born on August 5th, 1397. We wrote about Dufay’s life when we celebrated his birthday a year ago, so this time we’ll write about his place in the European musical canon. This place is unique: Dufay was one of the last Medieval and at the same time one of the first Renaissance composers. The music of the medieval period centered in Northern France, in Avignon, where seven popes (and several anti-popes) lived during the 14th century, and in Italy. The first significant polyphonic music was written during that time. Guillaume de Machaut was the most famous poet and composer of the period; he lived in Reims and worked in its famous cathedral, the crowning place of the French kings. It was a time of tremendous upheavals. The Hundred years’ war, which started in 1337 and lasted till 1453, devastated France (Reims, for example, fell to the English in 1370 and was liberated by Joan of Arc only in 1429). All the while Burgundy, a war ally of England, prospered. Through marriage or war, Burgundians expanded their territory, acquiring Flanders, Brabant, and many smaller principalities. These were the circumstances under which the cultural center of northern Europe shifted from France to Burgundy. The dukes, all of them patrons of arts (and often active practitioners), didn’t maintain one court, as did the French and English kings: Dijon was their administrative capital, but the court moved around the country, staying in Brussels, Bruges, Arras and other northern cities more often than in Dijon. Court musicians moved with the dukes, and many of these places were the court stayed became centers of music making. Dufay was the elder, and most revered, composer in a group that also included John Dunstaple, Gilles Binchois and Antoine Busnois. These were the first of what we now call Renaissance musicians. They introduced new esthetic sensibilities, which during the following two hundred years led to the development of an incredibly rich musical culture. The roots of the music of Palestrina, Orlando di Lasso, the Gabrielis and William Bird, which so often appears quite modern even to our ear, all go back to Dufay and the Burgundians. Not that Dufay was a completely modern composer. For him music was not only about the sound, the melody, or the aural interaction of voices in a polyphonic piece. It was also an intellectual game, in which a theme hidden from the listener could be valued for the pattern it creates on a sheet of music. But these were the vestiges of medieval music, famous for its complex arrangements, often more mathematical than esthetic. What his contemporaries valued the most were his melodic gifts, the beautiful polyphony of his masses, and the lively and graceful rhythms of some of his chansons.

Speaking of gracefulness: here is a good example, Dufay’s three-voiced hymn Ave Maris Stella ("Hail, star of the ocean"). It’s performed by the ensemble Pomerium under the direction of Alexander Blachly. And here is his Ballata “Resvellies Vous.” Dufay also used the melody to write an eponymous mass of which we can hear the first two parts, Kyrie and Gloria. All three of these pieces are performed by the ensemble Cantica Symphonia, conducted by Giuseppe Maletto.Permalink

July 21, 2014. From recent uploads. The American pianist Sean Chen was born in 1988 in Margate, Florida. He received his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees at Juilliard. While at school he won the 2010 Gina Bachauer Piano Competition, the 2010 Munz Scholarship, and first prize at the 2008 Juilliard Concerto Competition. 2013 was good for Mr. Chen: he won the American Pianists Association’s DeHaan Classical Fellowship and also the Third Prize at the 14th Van Cliburn International Piano competition. He has appeared as a soloist with several symphonies, among them the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra under Gerard Schwarz, the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra under Leonard Slatkin, and Indianapolis Chamber Orchestra. In 2014 he received the Artist Diploma at the Yale School of Music after studying with Hung-Kuan Chen and Tema Blackstone. You can listen to Mr. Chen’s lyrical and elegant interpretation of Chopin’s four Impromptus: Impromptu in A-flat Major, Op.29; Impromptu in F-Sharp Major, Op. 36; Impromptu in G-flat Major, Op. 51; and Fantaisie-Impromptu in C-Sharp minor, Op. 66 (it’s interesting to note that Chopin didn’t want Fantaisie-Impromptu to be published: the dedicatee and a friend, Julian Fontana, did it against his wishes. It became, as we know, one of Chopin’s most popular pieces).

the 2010 Munz Scholarship, and first prize at the 2008 Juilliard Concerto Competition. 2013 was good for Mr. Chen: he won the American Pianists Association’s DeHaan Classical Fellowship and also the Third Prize at the 14th Van Cliburn International Piano competition. He has appeared as a soloist with several symphonies, among them the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra under Gerard Schwarz, the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra under Leonard Slatkin, and Indianapolis Chamber Orchestra. In 2014 he received the Artist Diploma at the Yale School of Music after studying with Hung-Kuan Chen and Tema Blackstone. You can listen to Mr. Chen’s lyrical and elegant interpretation of Chopin’s four Impromptus: Impromptu in A-flat Major, Op.29; Impromptu in F-Sharp Major, Op. 36; Impromptu in G-flat Major, Op. 51; and Fantaisie-Impromptu in C-Sharp minor, Op. 66 (it’s interesting to note that Chopin didn’t want Fantaisie-Impromptu to be published: the dedicatee and a friend, Julian Fontana, did it against his wishes. It became, as we know, one of Chopin’s most popular pieces).

The violinist Yoo Jin Jang was born in Korea in 1990 and made her orchestral debut at the age of 10 with the KBS Symphony Orchestra. She received her Bachelor of Music degree from the Korean National University of Arts, and a Master of Music and Graduate Diploma from the New England Conservatory, where she studied with Miriam Fried. Currently she’s pursuing her Artist Diploma at the same school. In 2013, she won the 4th International Munetsugu Violin Competition (Shlomo Mintz was chairing the jury) and received on loan for two years the 1697 “Rainville” Stradivari violin. In 2010 she was the grand prix winner at the “Tchaikovsky’s Homeland” International Competition for Young Musicians, held in the cities of Izhevsk and Votkins, the birthplace of the composer. She also successfully participated in a number of international competitions. In March of 2014 she was in Chicago, playing at the Dame Myra Hess memorial concert. In her program were Four Romantic Pieces, Op.75 by Antonin Dvořák and Sonata for Violin and Piano by John Corigliano. Here’s what the composer writes about it: "The Sonata for Violin and Piano, written during 1962-63, is for the most part a tonal work, although it incorporates non-tonal and poly-tonal sections within it as well as other 20th century harmonic, rhythmic and constructional techniques. The listener will recognize the work as a product of an American writer, although this is more the result of an American writing music than writing ‘American’ music — a second-nature, unconscious action on my part." Here it is; Ms. Jang is accompanied by the pianist Renana Gutman.

received on loan for two years the 1697 “Rainville” Stradivari violin. In 2010 she was the grand prix winner at the “Tchaikovsky’s Homeland” International Competition for Young Musicians, held in the cities of Izhevsk and Votkins, the birthplace of the composer. She also successfully participated in a number of international competitions. In March of 2014 she was in Chicago, playing at the Dame Myra Hess memorial concert. In her program were Four Romantic Pieces, Op.75 by Antonin Dvořák and Sonata for Violin and Piano by John Corigliano. Here’s what the composer writes about it: "The Sonata for Violin and Piano, written during 1962-63, is for the most part a tonal work, although it incorporates non-tonal and poly-tonal sections within it as well as other 20th century harmonic, rhythmic and constructional techniques. The listener will recognize the work as a product of an American writer, although this is more the result of an American writing music than writing ‘American’ music — a second-nature, unconscious action on my part." Here it is; Ms. Jang is accompanied by the pianist Renana Gutman.

And finally, a performance by the newly formed (2012) Aizuri String Quartet. Even though the ensemble is very young, its members – violinists Miho Saegusa and Zoë Martin-Doike, Ayane Kozasa (viola), and Karen Ouzounian (cello) – are seasoned professionals who have won top prizes in such competitions as the Primrose International Viola Competition and Astral Artists National Auditions. They have collaborated with such artists as Pamela Frank, Miriam Fried, Richard Goode, Kim Kashkashian and Mitsuko Uchida. They studied together at The Curtis Institute of Music and The Juilliard School. Even prior to forming the quartet these musicians collaborated at many chamber music festivals, Marlboro, Caramoor and the Ravinia Festival’s Steans Music Institute among them. The Quartet gave its debut performance at the Tertulia Chamber Music series in New York City, and participated in the 2013 Juilliard String Quartet Seminar. Although new, the Quartet has been named the String Quartet-in-Residence at the Curtis Institute of Music beginning in September 2014, and this summer was the Quartet-in-Residence at the Ravinia Festival’s 2014 Steans Music Institute. It’s at one of the Steans concerts that they recorded Haydn’s Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 64, no. 3. You can listen to it here.

PermalinkJuly 14, 2014. Jacob Clemens non Papa. No big names this week, so we’ll go back some centuries and celebrate the Franco-Flemish composer Jacob Clemens non Papa. Jacob Clemens was born around 1510, a generation before Orlando di Lasso. He was probably born in Ypres, Flandres, the place now infamous for three horrible World War I battles and the first case in history when a poison gas was used on a large scale (another name for mustard gas is Yperite, after the city). At the time of Clemens’s birth, though, Ypres was a prosperous town, the third largest in Flandres after Bruges and Ghent and famous for its cloth trading. Nothing is known about Clemens’s early years, but he probably spent some time in Paris in the 1530s as a collection of his chansons was published there around that time. He sung in Bruges in 1544-45 and then moved to Antwerp where he struck a friendship with Tielman Susato, the famous music publisher and composer (several years earlier Susato founded a publishing house which used a press with the movable music type, the first in Flanders or the Low Countries). Later Susato would publish Clemens’s most famous work: his setting of all 150 psalms called Souterliedekens (Little Psalter Songs in Flemish). Souterliedekens were originally published in 1540 and were simple monophonic settings of the popular songs of the day. About 15 years later Clemens used these tunes to created short but beautiful polyphonic pieces, usually for three or four voices. Here, for example, is his setting of Psalm 31, performed by the Dutch ensemble Camerata Trajectina.

horrible World War I battles and the first case in history when a poison gas was used on a large scale (another name for mustard gas is Yperite, after the city). At the time of Clemens’s birth, though, Ypres was a prosperous town, the third largest in Flandres after Bruges and Ghent and famous for its cloth trading. Nothing is known about Clemens’s early years, but he probably spent some time in Paris in the 1530s as a collection of his chansons was published there around that time. He sung in Bruges in 1544-45 and then moved to Antwerp where he struck a friendship with Tielman Susato, the famous music publisher and composer (several years earlier Susato founded a publishing house which used a press with the movable music type, the first in Flanders or the Low Countries). Later Susato would publish Clemens’s most famous work: his setting of all 150 psalms called Souterliedekens (Little Psalter Songs in Flemish). Souterliedekens were originally published in 1540 and were simple monophonic settings of the popular songs of the day. About 15 years later Clemens used these tunes to created short but beautiful polyphonic pieces, usually for three or four voices. Here, for example, is his setting of Psalm 31, performed by the Dutch ensemble Camerata Trajectina.

In the 1550 he went to 's-Hertogenbosch, the city where one hundred years earlier Hieronymus Bosch was born. There, a local religious confraternity employed him as a singer and composer (it’s interesting that Bosch had been a member there). Jacob Clemens died (according to some sources a violent death) just five years later; he was 45 years old. One place Clemens never went to was Italy. That’s very unusual for a composer of his stature: practically all Franco-Flemish composers of his and even earlier generations – Jacob Obrecht, Josquin des Prez, Adrian Willaert, Jacques Arcadelt – spent at least some time in Italy, even before Palestrina, Orlando di Lasso and Tomás Luis de Victoria made it into the center of the musical world.

Even though his life was short, the prolific Clemens wrote a large amount of music, most of it sacred. 15 masses are extant, and the same number of Magnificats; he also wrote more than 200 motets and of course the abovementioned 150 settings of the Psalms. His secular music is mostly in the form of chansons, very popular at the time. Here is the Introit from his beautiful Requiem Mass. It’s performed by the Capella Palestrina, Maarten Michielsen conducting. And here is an excerpt from another mass by Jacob Clemens: Sanctus and Benedictus from Missa Pastores Quidnam Vidistis. Tallis Scholars are lead by Peter Phillips.

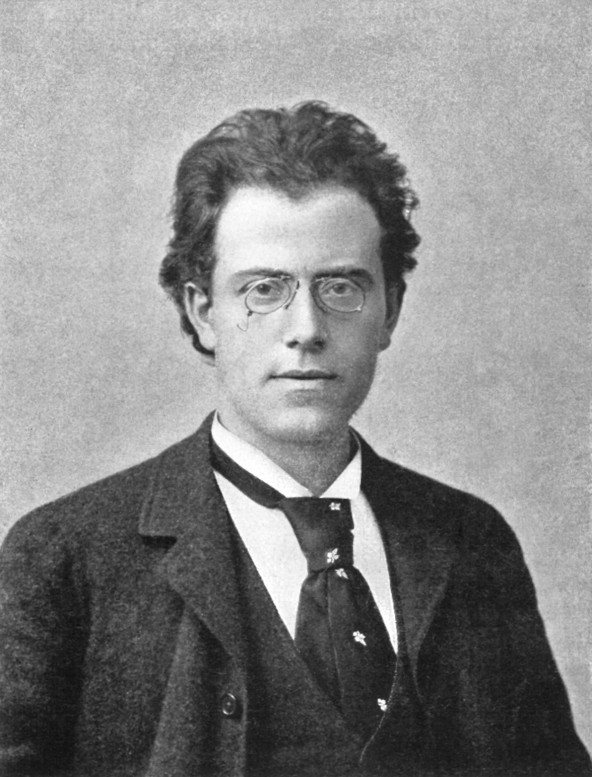

So why was Jacob Clemens called “non Papa” (not the Pope)? We don’t really know. Some suggested that the moniker was added to distinguish him from the Pope Clement VII (Giulio de’Medici, son of Giuliano, who, with his brother Lorenzo, co-ruled Florence), but it’s highly unlikely that anybody would mistake a Flemish composer for a pope. In addition, Clement VII died in 1534, when Jacob Clemens was in his 20s and still practically unknown. Most likely “non Papa” was added in jest, maybe by his friend Susato, and it stuck. There are no surviving portrait of “non Papa,” but in 1531 Sebastiano del Piombo, a friend of Michelangelo, created a fine portrait of Clement VII and you can see it above.

PermalinkJuly 7, 2014. Gustav Mahler was born on this day in 1860. When we celebrated his birthday a year ago we focused on his life around the time he composed the First symphony, which was completed in 1888. This time we’ll explore the period surrounding the writing of the Second symphony, the “Resurrection.” Mahler started composing the Second symphony soon after the completion of the First, in the same year of 1888. For several years Mahler had been the conductor of the Leipzig opera, finishing his career on a high note: he completed Carl Maria von Weber’s unfinished opera, Die drei Pintos, a project supported by the composer’s grandson, Carl von Weber. The performance was very successful and received considerable publicity: Tchaikovsky and other luminaries were in attendance. Around that time Mahler’s life became rather complicated, as he fell passionately in love with Carl’s wife, Marion. And there was no stability in his musical career. On the one hand, the success of the Die drei Pintos brought Mahler financial rewards and allowed him to quit his post in Leipzig (not without a scandal, as Mahler was a very demanding task master). On the other hand, his subsequent engagement with the Prague opera house was disappointing; he was fired after just several months. It was during that turbulent period that he wrote Totenfeier, a funeral march, which later became the first movement of the Second symphony. Despite all the scandals, in 1889 Mahler managed to secure a prestigious position as the conductor at the Royal Opera in Budapest. He stopped working on the Second symphony and would not resume it till 1893; instead, he concentrated on his conducting responsibilities in Budapest. That proved to be a challenging task, in large part because of the squabbles in the theater itself between the Hungarian musical “nationalist” and supporters of the German opera. There were highlights along the way, for example his staging of Don Giovanni, highly praised by Brahms. 1889 was the year of several personal tragedies: first his father Bernhard, then his 25 year-old sister Leopoldine, and his mother, to whom Gustav was very attached, all died in one year. And the premier of the First symphony, which he conducted in November of that year, was not successful. Not that Mahler didn’t compose at all; for example, he revised the First symphony and also composed several songs from Des Knaben Wunderhorn ('The Youth's Magic Horn'), a collection of German folk poems. One of these songs, “Urlicht” (“Primeval Light”) would later be incorporated into the Second Symphony.

surrounding the writing of the Second symphony, the “Resurrection.” Mahler started composing the Second symphony soon after the completion of the First, in the same year of 1888. For several years Mahler had been the conductor of the Leipzig opera, finishing his career on a high note: he completed Carl Maria von Weber’s unfinished opera, Die drei Pintos, a project supported by the composer’s grandson, Carl von Weber. The performance was very successful and received considerable publicity: Tchaikovsky and other luminaries were in attendance. Around that time Mahler’s life became rather complicated, as he fell passionately in love with Carl’s wife, Marion. And there was no stability in his musical career. On the one hand, the success of the Die drei Pintos brought Mahler financial rewards and allowed him to quit his post in Leipzig (not without a scandal, as Mahler was a very demanding task master). On the other hand, his subsequent engagement with the Prague opera house was disappointing; he was fired after just several months. It was during that turbulent period that he wrote Totenfeier, a funeral march, which later became the first movement of the Second symphony. Despite all the scandals, in 1889 Mahler managed to secure a prestigious position as the conductor at the Royal Opera in Budapest. He stopped working on the Second symphony and would not resume it till 1893; instead, he concentrated on his conducting responsibilities in Budapest. That proved to be a challenging task, in large part because of the squabbles in the theater itself between the Hungarian musical “nationalist” and supporters of the German opera. There were highlights along the way, for example his staging of Don Giovanni, highly praised by Brahms. 1889 was the year of several personal tragedies: first his father Bernhard, then his 25 year-old sister Leopoldine, and his mother, to whom Gustav was very attached, all died in one year. And the premier of the First symphony, which he conducted in November of that year, was not successful. Not that Mahler didn’t compose at all; for example, he revised the First symphony and also composed several songs from Des Knaben Wunderhorn ('The Youth's Magic Horn'), a collection of German folk poems. One of these songs, “Urlicht” (“Primeval Light”) would later be incorporated into the Second Symphony.

Mahler resigned from the Budapest Opera in 1891 and moved to Hamburg as the conductor of the Stadttheater. In his first season there he staged several Wagner operas, Tristan und Isolda among them. He also presented the German premier of Eugene Onegin, with Tchaikovsky, who was in attendance, admiring his conducting abilities. In the summer of 1892 he took the Hamburg opera company to London on a highly successful season of German opera. But then in the summer of 1893 he bought a cabin in Steinbach am Attersee, not far from Salzburg, and went there to compose. That established a pattern that he followed for many years; whether in Steinbach, or in later years in Maiernigg, he would leave the city for the place on a lake and spend the whole summer composing. In Steinbach he completed the Second Symphony and wrote the Third. There he also completed the Des Knaben Wunderhorn. The second (Andante Moderato) and the third (In ruhig fließender Bewegung – With quietly flowing movement) movements of the Second Symphony were completed in 1893, the fifth, final movement (Im Tempo des Scherzos – In the tempo of the scherzo) in 1894. The final movement was by far the longest (it usually takes 30 to 35 minutes to perform) and the most complex both thematically and in its orchestration, employing the chorus in the second part of the movement, the alto and soprano solos and even the organ. This is the movement in which the “Resurrection” theme is introduced. In the same 1894 he reedited the Totenfeie, the first movement, and added the orchestrated version of the song Urlich as the fourth movement.

Mahler conducted the premier in Berlin, in March of 1895, but performed just the first three movements. The premier of the complete symphony took place in December of the same year, with Mahler again conducting the Berlin Philharmonic. It was, somewhat surprisingly, very successful, much more so than the premier of the First. We’ll hear the complete symphony in the (tremendous, in our opinion) 1966 recording made by Sir Georg Solti with the London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Heather Harper is the soprano, Helen Watts – a wonderful contralto in the Ulrich movement.

PermalinkJune 30, 2014. Christoph Willibald Gluck at 300. We’ve never written about Gluck before, even though he was one of the most important composers of the 18th century: he composed mostly operas, and this genre is not well represented on Classical Connect. That’s why it’s a special pleasure to do so on his 300th birthday anniversary. Gluck was born on July 2nd of 1714 in Erasbach, now part of the town of Berching in Bavaria into a family of a forester. When Christoph was three, they moved to Bohemia where his father found a job as the head forester to Prince Lobkowicz (Lobkowiczes were an old noble family and patrons of art: two generations later Prince Joseph Franz Maximilian Lobkowicz would become a patron first of Haydn and then Beethoven; Haydn’s “Lobkowicz” quartet and several of Beethoven’s symphonies and quartets are dedicated to him). Christoph fell in love with music early and learned to play several instruments. As a teenager he left home and went to Prague to study music; he also enrolled in the university there but never finished his studies. In 1736 he went to Vienna. There his talents were noticed by an Italian nobleman who brought Christoph to Milan. He took musical lessons from Giovanni Battista Sammartini and wrote his first opera, Artaserse, which was premiered in 1741 at Teatro Ducal. The libretto of the opera was by Metastasio, probably the greatest and most prolific librettist of the time. Gluck stayed in Italy till 1745, writing several more operas, all to the texts of Metastasio. In 1745, already a well-known opera composer, he went to London to challenge Handel’s dominance of the opera scene; he wasn’t very successful. He left London a year later and for the next several years moved from one town to another, writing operas for theaters in Dresden, Vienna and Prague along the way. One of them was the very successful La clemenza di Tito on the libretto of Metastasio; it was performed in the famous Teatro di San Carlo in Naples (Mozart’s opera of the same title, his last one, used the libretto that was a reworking of Metastasio’s original).

anniversary. Gluck was born on July 2nd of 1714 in Erasbach, now part of the town of Berching in Bavaria into a family of a forester. When Christoph was three, they moved to Bohemia where his father found a job as the head forester to Prince Lobkowicz (Lobkowiczes were an old noble family and patrons of art: two generations later Prince Joseph Franz Maximilian Lobkowicz would become a patron first of Haydn and then Beethoven; Haydn’s “Lobkowicz” quartet and several of Beethoven’s symphonies and quartets are dedicated to him). Christoph fell in love with music early and learned to play several instruments. As a teenager he left home and went to Prague to study music; he also enrolled in the university there but never finished his studies. In 1736 he went to Vienna. There his talents were noticed by an Italian nobleman who brought Christoph to Milan. He took musical lessons from Giovanni Battista Sammartini and wrote his first opera, Artaserse, which was premiered in 1741 at Teatro Ducal. The libretto of the opera was by Metastasio, probably the greatest and most prolific librettist of the time. Gluck stayed in Italy till 1745, writing several more operas, all to the texts of Metastasio. In 1745, already a well-known opera composer, he went to London to challenge Handel’s dominance of the opera scene; he wasn’t very successful. He left London a year later and for the next several years moved from one town to another, writing operas for theaters in Dresden, Vienna and Prague along the way. One of them was the very successful La clemenza di Tito on the libretto of Metastasio; it was performed in the famous Teatro di San Carlo in Naples (Mozart’s opera of the same title, his last one, used the libretto that was a reworking of Metastasio’s original).

Gluck settled in Vienna in 1754, supporting himself as a Kapellmeister at the court of a wealthy patron. Italian operas, seria (serious) and buffa (comic), were dominating the Viennese scene, and they were getting stale. Many opera productions were turning into vehicles for singers who more interested in demonstrating their virtuosity than in music or drama. Gluck attempted to reform the opera, putting the emphasis on the story and musical development, rather than the coloratura (Richard Wagner had a similar impulse a century later). The first significant composition in this new style was Orfeo ed Euridice, which premiered in 1762. Till this day, it remains his most popular creation. The original Orfeo was the famous castrato Gaetano Guadagni; today this role is sometimes performed by mezzo-sopranos, high tenors (Juan Diego Flórez is a good example) or counter-tenors. Here’s Marilyn Horn as Orfeo in the famous aria Che farò senza Euridice? (What will I do without Euridice?). Georg Solti conducts the Covent Garden Orchestra.

One of Gluck’s pupils in Vienna was Princess Maria Antonia, who as Marie Antoinette would marry the future King of France Louis XVI in 1770. Gluck moved to Paris in 1773 and Marie Antoinette became his patron, helping him to secure a contract for six operas with the Paris Opera company. Gluck’s Iphigénie en Aulide, premiered in 1774, and the French remake of Orfeo were very successful. Unfortunately, several other operas failed to impress the public. Gluck was deeply hurt and left Paris for Vienna in May of 1776. In Paris the opera world was split between two camps: the supporters of Gluck and those who preferred operas of Niccolò Piccinni, a practically forgotten Italian who in the 1770s was probably the most popular opera composer in Europe. In Vienna Gluck was made a Court composer, but he would return to Paris on two more occasions, in 1777 and 1778. On the last trip he brought with him two of his latest operas, Iphigénie en Tauride and Echo et Narcisse. The former was a big success but the latter failed. To make things worse, during the rehearsals of Echo Gluck suffered a stroke. He left Paris for the last time in October of 1779. In Vienna he continued revising his older creations but never wrote anything major. He suffered two more strokes, the last of which killed him on November 15th, 1787. Let’s listen to the overture to Iphigénie en Aulide; it’s played in its original form, how Gluck wrote it rather that the popular Wagner revision. John Eliot Gardiner conducts the Lyon Opera Orchestra.

PermalinkJune 23, 2014. Busnois and Gounod. This week we’ll look back at the early years of modern Western music and commemorate a composer who made a very significant contribution to its development. We’ve never writtenabout Antoine Busnois, even though he was one of the most famous composers of the generation following Guillaume Dufay. Busnois was born around 1430, probably in or around the town of Béthune in what is now the northeastern corner of France, but back then part of the county of Artois. In the first part of the 15th century Artois, sandwiched between Picardy and Flandres, was a Burgundian possession. Busnois may have come from an aristocratic family, which would explain why his name was mentioned at the French Royal court in 1550. Ten years later he was employed in Tours, first at the cathedral, and later at the church of St. Martin. Apparently he was a rather rambunctious fellow: a complaint filed against him and his five companions states that they beat up a priest “not once but five times.” This was not his only brush with the law: he got excommunicated for celebrating the Mass without being an ordained priest. The pope Pius II, himself an adventurer and author of erotic writings, later pardoned Busnois. While at St. Martin’s he befriended another composer, Johannes Ockeghem, who at the time served as the church’s treasurer. In 1465 Busnois went to Poitiers, where he became a choirmaster, but just a year later he moved to Burgundy were he was hired by the court of Charles the Bold as a singer and composer. Charles fought many wars (and eventually was killed at the Battle of Nancy), and it seems Busnois accompanied him on many of his military campaigns. After Charles’s death in 1477, Busnois stayed with the court for another five years and then retired. Not much in known about the last 10 years of his life; he died in Bruges on November 6th, 1492.

around 1430, probably in or around the town of Béthune in what is now the northeastern corner of France, but back then part of the county of Artois. In the first part of the 15th century Artois, sandwiched between Picardy and Flandres, was a Burgundian possession. Busnois may have come from an aristocratic family, which would explain why his name was mentioned at the French Royal court in 1550. Ten years later he was employed in Tours, first at the cathedral, and later at the church of St. Martin. Apparently he was a rather rambunctious fellow: a complaint filed against him and his five companions states that they beat up a priest “not once but five times.” This was not his only brush with the law: he got excommunicated for celebrating the Mass without being an ordained priest. The pope Pius II, himself an adventurer and author of erotic writings, later pardoned Busnois. While at St. Martin’s he befriended another composer, Johannes Ockeghem, who at the time served as the church’s treasurer. In 1465 Busnois went to Poitiers, where he became a choirmaster, but just a year later he moved to Burgundy were he was hired by the court of Charles the Bold as a singer and composer. Charles fought many wars (and eventually was killed at the Battle of Nancy), and it seems Busnois accompanied him on many of his military campaigns. After Charles’s death in 1477, Busnois stayed with the court for another five years and then retired. Not much in known about the last 10 years of his life; he died in Bruges on November 6th, 1492.

Busnois wrote a number of masses of which three survive, one being one of the earliest renditions of Missa L'homme armé. He also wrote a number of motets. Here’s his very short motet Alleluia, Verbum caro factum est, performed by the ensemble Capilla Flamenca. But it was not church music that Busnoise was mostly famous for; it was his chansons, of which more than 60 are extant. Here’s a tune he made popular all over Europe – many composers reworked it either as chansons or used it as cantus firmus in their masses. It’s called Fortuna desperata, and is sung by Musica Antiqua of London. And here’s another chanson, called Amours nous traitte honnestement; it’s for four voices and is performed by the ensemble Capella Sancti Michaelis.

On a very different note, we missed a recent birthday of the French composer Charles Gounod, who was born on June 17th of 1818, the same day as Igor Stravinksy, about whom we wrote last week. Gounod’s success can be attributed to just one major composition, the opera Faust, and his Ave Maria, an instrumental piece based on Prelude no. 1 in C Major from Book I of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier. Still, this is much more than many composers have ever achieved, and Gounod’s melodic gift was very influential during the second half of the 19th century. Faust was premiered in 1859 at the Théatre-Lyrique (the Paris Opera rejected it) and was not well received, but when revived at the Opera three years later, it became an immediate hit. Here’s Maria Callas singing the famous Jewel Song from Act 3. Georges Prêtre conducts the Orchestre de la Société Des Concerts du Conservatoire. The recording was made in 1963, at the end of Callas’s career.

Permalink