Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

September 8, 2014. A remarkable week. Almost every year the second week of September brings an exceptionally large number of anniversaries: depending on the year, eight or nine birthdays of eminent composers fall within these seven days. This year the composers are: Antonin Dvořák, born on this, September 8th, in 1841, Henry Purcell – on September 10th of 1659; then the following day, the 11th of September, is the birthday of William Boyce, one of the most important English composers of the 18th century. On the same day, but almost three centuries later, in 1935, the wonderful Estonian composer Arvo Pärt was born. And that’s not all –September 13th is the birth date of three composers: Girolamo Frescobaldi in 1583, Clara Schumann in 1819, and Arnold Schoenberg in 1874. Michael Haydn, the younger brother of Joseph and an excellent composer in his own right, was born on September 14th of 1737, and finally Luigi Cherubini was also born on September 14th, in 1760. In the past we’ve written about some about these composers, this week we’ll turn to an Italian, Girolamo Frescobaldi.

Frescobaldi was the first European composer to write mostly for a keyboard instrument; practically all music written by his great predecessors such as Orlando di Lasso and Claudio Monteverdi, was vocal and instrumental. His organ music influenced generations of composers, including Johann Sebastian Bach. One of Frescobaldi’s most important compositions was a 1635 collection of several Masses and other liturgical music called Fiori Musicali (Musical flowers). Parts of the Fiori were included in the famous book by Johann Joseph Fux called Gradus ad parnassum, a treatise on counterpoint written in 1725 but used as a textbook till the late 19th century (Mozart, Haydn and Beethoven all used it in their studies). Bach copied the text of Fiori with his own hand. The three masses of the Fiori are: Missa della Domenica, Missa degli Apostoli, and Missa della Madonna. We’ll hear the first one, Missa della Domenica in the performance by the organist Roberto Loreggian. You’ll also hear the choir of Schola Gregoriana Scriptoria directed by Nicola M. Bellinazzo.Permalink

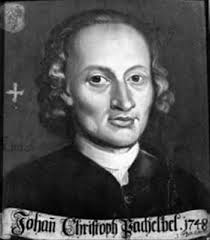

September 1, 2014. Pachelbel, Bruckner and more. Had he been alive, Johann Pachelbel would probably be very upset with the enormous popularity of his Cannon in D. A prolific composer, he wrote a large body of music, both secular and sacred, which these days is completely overshadowed by this one piece. During his lifetime, though, Pachelbel was famous as a composer but also as an organist and music teacher. He was born on September 1st of 1653 in Nuremberg, Bavaria. From a young age he studied music with different local organists, and then attended the famous University of Altdorf (Leibniz studied there). At the age of 16 he was made an organist in the St. Lorenz church. In 1673 he went to Vienna and was appointed a deputy organist at the St-Stephen’s Cathedral, the main church of Austria. He stayed in Vienna for the next five formative years, during which he met with many leading composers and musicians. In 1677 he moved to Eisenach (Johann Sebastian Bach would be born there eight years later) as a court organist to the Duke of Saxe-Eisenach. While there he became a good friend of Johann Sebastian’s father, Johann Ambrosius. Pachelbel’s story is intertwined with that of the Bach family: in 1678 Pachelbel moved to Erfurt were many of the Bachs lived; he became a godfather to one of Johann Sebastian’s sisters, lived in the house of another member of the Bach family and taught music to Johann Christoph, J.S’s oldest brother. Pachelbel stayed in Erfurt till 1690 and then left seeking better employment. In 1694, during the wedding celebration of his former pupil, Johann Christoph Bach, he met, for the only time, the nine-year-old Johann Sebastian. For a while Pachelbel moved from one city to another and 1695 returned to his native Nuremberg, as a famous composer invited by the city council. He lived in Nuremberg for the rest of his life; Pachelbel died on March 3rd of 1706. In 1699, in Nuremberg, he composed one of his most important pieces, Hexachordum Apollinis ("Six Strings of Apollo"), a set of six arias followed by variations, which, according to Pachelbel himself, could be performed either on the organ or the harpsichord. Variations were a somewhat new musical form in the 17th century, and Hexachordum was by far the most interesting set of variations written to date. Pachelbel dedicated the work to the German-Danish composer Dieterich Buxtehude who hugely influenced the young Johann Sebastian Bach. We’ll hear the organ version of the first Aria, Aria Prima, followed by six variations. The organist is John Butt.

these days is completely overshadowed by this one piece. During his lifetime, though, Pachelbel was famous as a composer but also as an organist and music teacher. He was born on September 1st of 1653 in Nuremberg, Bavaria. From a young age he studied music with different local organists, and then attended the famous University of Altdorf (Leibniz studied there). At the age of 16 he was made an organist in the St. Lorenz church. In 1673 he went to Vienna and was appointed a deputy organist at the St-Stephen’s Cathedral, the main church of Austria. He stayed in Vienna for the next five formative years, during which he met with many leading composers and musicians. In 1677 he moved to Eisenach (Johann Sebastian Bach would be born there eight years later) as a court organist to the Duke of Saxe-Eisenach. While there he became a good friend of Johann Sebastian’s father, Johann Ambrosius. Pachelbel’s story is intertwined with that of the Bach family: in 1678 Pachelbel moved to Erfurt were many of the Bachs lived; he became a godfather to one of Johann Sebastian’s sisters, lived in the house of another member of the Bach family and taught music to Johann Christoph, J.S’s oldest brother. Pachelbel stayed in Erfurt till 1690 and then left seeking better employment. In 1694, during the wedding celebration of his former pupil, Johann Christoph Bach, he met, for the only time, the nine-year-old Johann Sebastian. For a while Pachelbel moved from one city to another and 1695 returned to his native Nuremberg, as a famous composer invited by the city council. He lived in Nuremberg for the rest of his life; Pachelbel died on March 3rd of 1706. In 1699, in Nuremberg, he composed one of his most important pieces, Hexachordum Apollinis ("Six Strings of Apollo"), a set of six arias followed by variations, which, according to Pachelbel himself, could be performed either on the organ or the harpsichord. Variations were a somewhat new musical form in the 17th century, and Hexachordum was by far the most interesting set of variations written to date. Pachelbel dedicated the work to the German-Danish composer Dieterich Buxtehude who hugely influenced the young Johann Sebastian Bach. We’ll hear the organ version of the first Aria, Aria Prima, followed by six variations. The organist is John Butt.

Anton Bruckner was born on September 4th of 1824. Last year we wrote about his Symphony no. 5; this year we’ll go back several years, to Bruckner’s Symphony no. 1. This symphony was the first one deemed by Bruckner to be good enough to be published: he wrote a Study Symphony in F minor before that, but didn’t like it. The symphony was written between January of 1865 and April of 1866, so Bruckner was already 41 when its first version was completed. At the time he was living in Linz and working as the organist at Stadtpfarrkirchen, the parish church of the Assumption. During that time Bruckner, already a composer of some renown, undertook very unusual studies with Simon Sechter, a Viennese specialist in music theory, to better learn the counterpoint. Most of the teaching was done by correspondence, plus Bruckner’s infrequent visits to Vienna. The very first version of the symphony was performed in 1868, with Bruckner conducting. Bruckner famously lacked any confidence in his talent and was susceptible to opinions of critics and even students. That led to numerous revisions of his works. The First symphony was no exception. In 1877 and then in 1884 he created what is called the Linz Version (even though by that time Bruckner was already residing in Vienna). He returned to the work in 1891 (the so-called "Vienna version") and then again in 1893. We’ll hear the "Linz version," the one that is recorded most often. The conductor is Bernard Haitink, with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. This live 1974 recording runs about 45 minutes.

Three more very talented composers were born this week: Pietro Locatelli on September 3rd of 1695, Darius Milhaud on September 4th of 1892, and Johann Christian Bach (the “London Bach”) – on September 5th of 1735. We’ll have to write about them another time.Permalink

August 25, 2014. Johannes Brahms, 7 Fantasien, op. 116. This set of miniatures, sometimes called Seven Fantasies, was written by Brahms in 1892. Popular both with the listeners and performers, it is represented in our library with the recordings made by the young English pianists Sam Armstrong and Ashley Wass; Israel-born Benjamin Hochman and Rafael Skorka; the Russian pianist Yury Shadrin; and the Americans Christopher Atzinger and David Kaplan. Joseph DuBose takes an in-depth look into this piano masterpiece by the German composer. Read the complete article and listen to the Fantasies here.

English pianists Sam Armstrong and Ashley Wass; Israel-born Benjamin Hochman and Rafael Skorka; the Russian pianist Yury Shadrin; and the Americans Christopher Atzinger and David Kaplan. Joseph DuBose takes an in-depth look into this piano masterpiece by the German composer. Read the complete article and listen to the Fantasies here.

One of the several offspring of the Romantic period, and developing nearly contemporaneously with the German Lied, the piano miniature opened to composers a world as vastly rich and imaginative as the larger forms handed down from the Classical masters – indeed, perhaps even more so. With the nocturnes of John Field among its earliest examples, the piano miniature was further developed by the same hands that brought the German Lied into maturity – Franz Schubert and Robert Schumann – as well as in the many "dances" of Frédéric Chopin. Like the Lied, the miniature was given a deeply philosophical expression, and rendered with such remarkable introspection and calculated effect, by Johannes Brahms.

Though Brahms was widely considered the immediate heir of Beethoven and Schumann, in opposition to the New German School of Liszt and Wagner, it is his several collections of miniatures rather than his sonatas that are perhaps the most brilliant gems of his output as a composer of piano music. Somewhat curiously, Brahms composed his only three piano sonatas, a form which, like the symphony, was a staple of the Classical composer, very early in his career. From thence he conquered the challenges of the large-scale variation set during the middle of his career. His earliest efforts in the realm of the miniature followed quickly on the heels of the completion of the third and last piano sonata with the composition of the opus 10 Ballades during the summer of 1854. However, twenty-five years would pass before Brahms once again composed a set of miniatures. In 1879-80, two important sets appeared: the eight Klavierstücke, op. 76 (played here by Sam Armstrong) and the two Rhapsodies, op. 79 (no. 1 and no. 2, played by Michael Krücker and Dmitry Paperno, respectively). Most notable is the Klavierstücke, which built upon the basic groundwork laid by the Ballades, and further set the stage for Brahms’s final essays in the genre, as well as his last works for the piano.

During the early 1890s, Brahms compiled together the twenty pieces that were published during 1892-93 as the opp. 116-19. It is acknowledged that he composed more than the twenty pieces known to us today, and it is possible that some were drafted earlier. However, it is generally accepted that most of the pieces were composed roughly close to their dates of publication. As a whole, these pieces display Brahms as intensely meditative; combined with opus 76, they are a gradual progression away and an ultimate departure from the extroverted Sturm und Drangstyle of his more youthful years; taken as a part of his entire output for the piano, they are an immensely rich and imaginative culmination, and quite easily some of the most beautiful music composed for the instrument.

Of these four later sets, opus 116 is unique among its companions. [continued]Permalink

August 18, 2014. Salieri, Enesco and Debussy. Antonio Salieri was born on this date in 1750 in Legnago, Veneto. His brother, a student of Giuseppe Tartini, was Antonio’s first music teacher. Their parents died when Salieri was 14 and he ended up in Venice, the ward of a local nobleman. He continued his musical studied in Venice and soon was noticed by Florian Leopold Gassmann, a chamber composer to the Austrian Emperor Joseph II. In 1766, Gassmann brought Salieri to Vienna. Gassmann gave the youngster composition lessons and, more importantly, brought him to the court to attend the evening chamber concerts. The Emperor noticed the young man; that started a relationship, which lasted till the Emperor’s death in 1790. Salieri also made several important acquaintances: one with Metastasio, probably the most famous librettist of opera seria, another with the great composer, Christoph Willibald Gluck. Armida, Salieri’s 6th opera, was composed in 1771 when Salieri was just 21. His first big success, it was strongly influenced by Gluck. The libretto was based on a story from Torquato Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberate; it followed several illustrious operas on the same subject, such as Armide by Jean-Baptiste Lully (1686), George Frideric Handel’s Rinaldo (1711) and Armida al campo d'Egitto (1718) by Antonio Vivaldi (1718). Upon completion of Armida, Salieri wrote an even more popular La fiera di Venezia (The Fair of Venice). Everything was looking up in Salieri’s life; the first encounter with Mozart would have to wait for another 10 years… Here’s the Overture to Armida; the Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra is conducted by Michael Dittrich.

Venice, the ward of a local nobleman. He continued his musical studied in Venice and soon was noticed by Florian Leopold Gassmann, a chamber composer to the Austrian Emperor Joseph II. In 1766, Gassmann brought Salieri to Vienna. Gassmann gave the youngster composition lessons and, more importantly, brought him to the court to attend the evening chamber concerts. The Emperor noticed the young man; that started a relationship, which lasted till the Emperor’s death in 1790. Salieri also made several important acquaintances: one with Metastasio, probably the most famous librettist of opera seria, another with the great composer, Christoph Willibald Gluck. Armida, Salieri’s 6th opera, was composed in 1771 when Salieri was just 21. His first big success, it was strongly influenced by Gluck. The libretto was based on a story from Torquato Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberate; it followed several illustrious operas on the same subject, such as Armide by Jean-Baptiste Lully (1686), George Frideric Handel’s Rinaldo (1711) and Armida al campo d'Egitto (1718) by Antonio Vivaldi (1718). Upon completion of Armida, Salieri wrote an even more popular La fiera di Venezia (The Fair of Venice). Everything was looking up in Salieri’s life; the first encounter with Mozart would have to wait for another 10 years… Here’s the Overture to Armida; the Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra is conducted by Michael Dittrich.

George Enescu was born on August 19th of 1881, the same year as Béla Bartók. The greatest Romanian composer (probably the only great Romanian composer), he was born in a small village in the historical Moldavia, on the border with Bukovina. A child prodigy, he started composing at the age of five. At the age of seven, he was admitted to the Vienna Conservatory, the youngest person ever. There he studied the violin, the piano and composition. At the age of 10 he was presented to the court and played to the Emperor Franz Joseph. At the age of 13 he moved to Paris and went to the Paris Conservatory where he studied with André Gedalge, the teacher of Ravel, Honegger and many other soon to be famous composers. Like Bartók who was so influenced by the folk music of Hungary and Romania, Enescu liberally borrow from the tunes of his native country. In 1901, at just twenty years old, he wrote two Romanian Rhapsodies, Op. 11, which remained his most popular compositions (quite to his chagrin, as he thought they overshadowed his more mature compositions). Here’s the first of the two, Romanian Rhapsody no.1, played by the London Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Antal Dorati. Enescu traveled to the US for the first time in 1923 and many times thereafter, performing as a conductor and a violinist. He lived mostly in Paris and Bucharest. During World War II he stayed in Romania, and made several recording with the great pianist Dinu Lipatti. When the Soviets took over, he moved back to Paris. He died there on May 4th, 1955.

We love Claude Debussy, which of course is a truism: who doesn’t? Somehow, no matter how overplayed his music is, it manages to stay fresh. He was born on August 22nd, 1862. We wrote about him many times, so on this occasion we’ll just play some of his music. Robert Casadesus was one of the great interpreters of the music of Debussy. He often played with his wife, also a pianist, Gaby. Here they are in the Petite Suite for piano four hands, composed in 1886-1889. The recording was made in 1962.

PermalinkAugust 11, 2014. A minor constellation. Several composers were born this week, none of them of the finest caliber but all talented and very much worth writing about. Heinrich Ignaz Biber, an Austrian-Bohemian composer, was born on August 12th, 1644 in Wartenberg, a small town in Bohemia which is now called Stráž pod Ralskem. Just to place Biber historically: he was seven years younger than Dieterich Buxtehude and nine years older than Arcangelo Corelli – and about 40 years older than J.S. Bach. Little is known about his childhood, but we do know that around 1668 he worked at the court of Prince Eggenberg in Graz, Austria, and two years later he was already in Kremsier, Moravia working for the Bishop of Olomouc. By then the 26 year-old Biber was already quite famous as a violin player. In 1670 Biber, without asking the Bishop’s permission, abruptly quit his employ and joined the court of the Archbishop of Salzburg. He stayed there for the rest of his life. Biber’s career flourished: he became the Kapellmeister in charge of all music making at the court of the Archbishop (100 years later the same court would employ the young Mozart), he was titled by the Emperor Leopold, and the Archbishop bestowed titles upon him. While in Salzburg, Biber wrote quite a bit of church music and even several operas, but the most famous works in his output is a collection of 16 pieces, 15 sonatas plus a Passacaglia for solo violin, known as either The Rosary Sonatas or the Mystery Sonatas; they were written around 1676. Here’s the first of the Sonatas, subtitled The Annunciation. It’s performed by Andrew Manze, violin and Richard Egarr, organ. Biber’s Passacaglia is probably the first significant piece ever written for the solo violin. You can listen to it here, performed by Reinhard Goebel. Biber’s music enjoyed great popularity, but soon after was overshadowed by Corelli’s. There has been a renaissance of it lately, though, especially after the commemoration of Biber’s death in 2004

in Wartenberg, a small town in Bohemia which is now called Stráž pod Ralskem. Just to place Biber historically: he was seven years younger than Dieterich Buxtehude and nine years older than Arcangelo Corelli – and about 40 years older than J.S. Bach. Little is known about his childhood, but we do know that around 1668 he worked at the court of Prince Eggenberg in Graz, Austria, and two years later he was already in Kremsier, Moravia working for the Bishop of Olomouc. By then the 26 year-old Biber was already quite famous as a violin player. In 1670 Biber, without asking the Bishop’s permission, abruptly quit his employ and joined the court of the Archbishop of Salzburg. He stayed there for the rest of his life. Biber’s career flourished: he became the Kapellmeister in charge of all music making at the court of the Archbishop (100 years later the same court would employ the young Mozart), he was titled by the Emperor Leopold, and the Archbishop bestowed titles upon him. While in Salzburg, Biber wrote quite a bit of church music and even several operas, but the most famous works in his output is a collection of 16 pieces, 15 sonatas plus a Passacaglia for solo violin, known as either The Rosary Sonatas or the Mystery Sonatas; they were written around 1676. Here’s the first of the Sonatas, subtitled The Annunciation. It’s performed by Andrew Manze, violin and Richard Egarr, organ. Biber’s Passacaglia is probably the first significant piece ever written for the solo violin. You can listen to it here, performed by Reinhard Goebel. Biber’s music enjoyed great popularity, but soon after was overshadowed by Corelli’s. There has been a renaissance of it lately, though, especially after the commemoration of Biber’s death in 2004

The English composer Maurice Greene was born on the same day, August 12th, but in London in 1696. Greene became an organist at the St.-Paul Cathedral, a prestigious position, in 1718. Around this time he and George Frideric Handel became good friends. Unfortunately, sometime later they had a tremendous fallout and, to quote the English music historian Charles Burney, “for many years of his life, [Handel] never spoke of [Greene] without some injurious epithet.” This row with Handel led Greene into the famous “Bononcini affair.” The Italian composer Giovanni Bononcini, Handel’s rival, was accused of plagiarism (he tried to pass Antonio Lotti’s madrigal as his own), but it was Greene who brought the madrigal to the public’s attention, trying to prop up Bononcini at Handel’s expense. Bononcini had to leave London, while Greene was forced to quit the Academy of Ancient Music, which he co-founded some years earlier. Fortunately for Greene, this episode didn’t affect his social position: some years later he was appointed organist and composer of the Chapel Royal. Herer’s one of Greene’s most famous anthems, Lord, Let Me Know Mine End. It’s performed by the Choir of Christ Church Cathedral with Stephen Farr on the organ.

The French composer Jacques Ibert was born on August 15th of 1890. His father was a successful trader and his mother a good amateur pianist. Jacques started studying the violin at the age of four and later took piano lessons. In his youth he supported himself as an accompanist and a cinema pianist. He took several courses at the Paris Conservatory and also attended private classes with André Gedalge, a teacher and composer. There he met Arthur Honegger and Darius Milhaud, two young composers who would later, together with Poulenc, Auric, Durey and Tailleferre form a group called Les Six. Ibert never joined in as during those years he stayed mostly away from Paris: during the Great War he was a naval officer and then, returning to Paris, he won the Prix de Rome on the first attempt and went to Italy. Ibert was an eclectic composer who used different styles. One of his early successes was a very impressionistic Escales (Ports of Call), inspired by his years in the Navy. The ports are Rome, Palermo, the exotic Nefta in Tunis and Valencia. Here it is, with Charles Munch conducting the Boston Symphony.

Sorabji and Pierné, the antipodes, were also born this week but will have to wait till next year.

PermalinkAugust 4, 2014. The Great War. We’d like to commemorate in our own small way, one of the most profound events in modern history, The First World War. It started 100 years ago with Austria-Hungary attacking Serbia in a reprisal for the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Russia, Serbia’s ally, mobilized their armies. Other great powers – Germany, France and Britain – followed the suit. Very soon, events snowballed out of control: Germany invaded neutral Belgium and then France, Britain declared war against Germany, and a war that would last four years and result in 16 million deaths and 20 million wounded was on. Even though casualties for Russia and France were higher, Britain lost more composers on the front. George Butterworth joined the British army at the beginning of the war. At 29, he was known as a composer of great promise. His song cycle A Shropshire Lad and a short symphonic poem The Banks of Green Willow were premiered to critical acclaim in the year before the war (here it is, performed by the English String Orchestra, William Boughton conducting). Butterworth was killed on August 5th, 1916 during the terrible Battle of Somme, which saw more than 1,000,000 soldiers killed or wounded. Also killed was Cecil Coles, a young Scottish composer. Like Butterworth, Coles was a friend of Gustav Holst and Ralph Vaughan Williams. Holst didn’t serve, but Williams enlisted into the medical corps. His Third Symphony (Pastoral) was inspired by a bugle call he heard during the war and, in his own words, referenced the fields of France. And many years later Benjamin Britten wrote one of his finest compositions, the War Requiem, the text for which included poems of Wilfred Owen, written during the war. Owen was killed in November of 1918, one week before the end of the war; he was 25.

Of the French composers, Ravel was probably affected more than anybody else. He dreamed of being a military pilot, but his poor health and pretty short stature (he was 5’3) prevented him from joining the French Air Force. Instead, he became a truck driver and was stationed near Verdun. He found time to compose, and between 1914 and 1917 wrote a piano suite called Le tombeau de Couperin. The suite consists of six parts, and each one is dedicated to a friend who died in the war. The first piece, Prelude, is dedicated to First Lieutenant Jacques Charlot, who transcribed Ravel’s “Mother Goose”suite for piano solo. Charlot was killed in 1915; Debussy also dedicated to Charlot a section of his suite for two pianos En blanc et noir. Toccata, the last piece of Le tombeau, is dedicated to the memory of Captain Joseph de Marliave, husband of Marguerite Long. De Marliave was killed days after the beginning of the hostilities, in August of 1914. Marguerite Long played the premier of Le tombeau after the war. You can hear it in the performance by Alon Goldstein. In 1929, Ravel wrote a Piano Concerto for Left Hand for the pianist Paul Wittgenstein, who lost his right hand on the front (Leon Fleisher performs it here, Seiji Ozawa conducts Boston Symphony Orchestra).

In Germany and Austria-Hungary very little music was written during the war. Richard Strauss wrote his rather dull Alpine Symphony and even more boring opera Die Frau ohne Schatten. Arnold Schoenberg, who was then forty, was sent to the front and didn’t write anything of significance during the wartime. All that Anton Webern wrote during that time were several songs. The only composer to remain productive was Alban Berg. He served in the Austro-Hungarian army from 1915 to 1918, and while on leave in 1917 and 1918 he wrote large parts of his first masterpiece, the appropriately macabre opera Wozzeck.

Igor Stravinsky presents an interesting case. Some episodes of The Right of Spring, such as Dance of the Earth or Sacrificial Dance, seem to foreshadow the war (Le Sacre was written in 1913). On the other hand, most of the music written in neutral Switzerland, were Stravinsky’s family spent the war years, is simpler, lighter, often based on folk music. Such are his Les Noces (The Wedding), a “ballet with voices,” the opera-ballet Renard and the musical play L'Histoire du soldat. This development almost inevitably lead into his neoclassical period. The order, balance, the stillness of neoclassical music were a reflection of similar trends in visual arts. To a large extent these were reactions to the unpredicatbility, the anarchy and of course the terrible pain of the war. In Italy and Germany, neoclassical art very soon morphed into the art of fascism. Fortunately for us, abstract music escaped this path.Permalink