Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

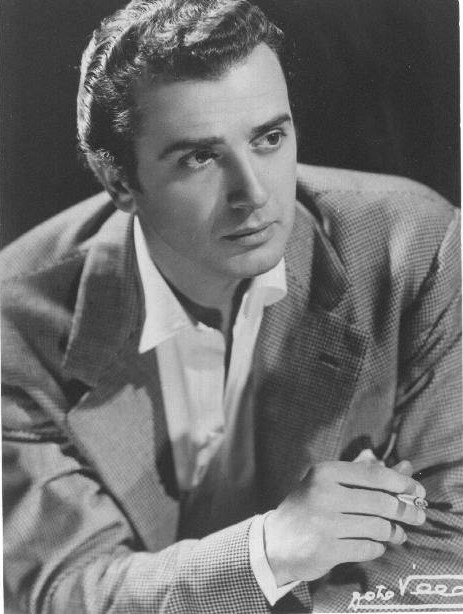

This Week in Classical Music: April 19, 2021. Franco Corelli. For the past two weeks we’ve been so busy with Karajan that we missed an important date: the 100th anniversary of Franco Corelli. Corelli was one of the greatest tenors of the 20th century, who excelled on the biggest opera stages of Europe and America and left a wonderful recording legacy. He had a clear, powerful voice with a wide range, what the Italians call “spinto” tenor: he could handle both the dramatic roles (think of Mario del Monaco in the role of Canio in Pagliacci or Radames in Aida) and the lyric ones (like Pavarotti singing Rodolfo in La Boheme). It didn’t hurt that Corelli was also a handsome man with good acting abilities. Franco Corelli was born in Ancona on April 8th of 1921. His grandfather was a successful opera singer and many other family members sung either professionally or as amateurs. For a while Corelli studied at the Pesaro Conservatory, but soon decided that he didn’t like voice teachers; from that time on he was mostly self-taught. Corelli made his operatic debut in 1951 in Spoleto, singing Don José in Carmen. In 1952 he sung in the Rome Opera and joined it in 1953. That same year he sung Pollione in Norma, with Maria Callas performing the title role. In 1954 he made his debut in the famed La Scala, again singing with Callas in Spontini's opera La vestale (the opera is rarely staged these days, but YouTube has both the full opera and also this wonderful scene). Corelli would appear with Callas many times, both in La Scala and at the Met. He was asked to perform in the best opera theaters of Italy; then, in 1957, he appeared in Vienna’s State Opera, and the same year made a sensational debut in the Covent Garden, singing Cavaradossi in Tosca. The following year he went to the US, singing in Chicago and San Francisco, and in 1961 made his debut at the Met. During these years he sung with the best sopranos of the generation, Maria Callas, his favorite, Renata Tebaldi, Magda Olivero, the mezzo Giulietta Simionato and, later, Joan Sutherland. At the Met he sung with Leontine Price (she was his Leonora when Corelli sung Manrico in Il Trovatore in his first appearance at the theater) and Birgit Nilsson (their Turandot was spellbinding). Corelli sung at the Met for ten years, giving 282 performances of 18 roles.

opera stages of Europe and America and left a wonderful recording legacy. He had a clear, powerful voice with a wide range, what the Italians call “spinto” tenor: he could handle both the dramatic roles (think of Mario del Monaco in the role of Canio in Pagliacci or Radames in Aida) and the lyric ones (like Pavarotti singing Rodolfo in La Boheme). It didn’t hurt that Corelli was also a handsome man with good acting abilities. Franco Corelli was born in Ancona on April 8th of 1921. His grandfather was a successful opera singer and many other family members sung either professionally or as amateurs. For a while Corelli studied at the Pesaro Conservatory, but soon decided that he didn’t like voice teachers; from that time on he was mostly self-taught. Corelli made his operatic debut in 1951 in Spoleto, singing Don José in Carmen. In 1952 he sung in the Rome Opera and joined it in 1953. That same year he sung Pollione in Norma, with Maria Callas performing the title role. In 1954 he made his debut in the famed La Scala, again singing with Callas in Spontini's opera La vestale (the opera is rarely staged these days, but YouTube has both the full opera and also this wonderful scene). Corelli would appear with Callas many times, both in La Scala and at the Met. He was asked to perform in the best opera theaters of Italy; then, in 1957, he appeared in Vienna’s State Opera, and the same year made a sensational debut in the Covent Garden, singing Cavaradossi in Tosca. The following year he went to the US, singing in Chicago and San Francisco, and in 1961 made his debut at the Met. During these years he sung with the best sopranos of the generation, Maria Callas, his favorite, Renata Tebaldi, Magda Olivero, the mezzo Giulietta Simionato and, later, Joan Sutherland. At the Met he sung with Leontine Price (she was his Leonora when Corelli sung Manrico in Il Trovatore in his first appearance at the theater) and Birgit Nilsson (their Turandot was spellbinding). Corelli sung at the Met for ten years, giving 282 performances of 18 roles.

Corelli performed at the highest level for about 20 years, but in the early 1970s his voice became a little tired, making Corelli nervous. He later said that at that time he could either eat or sleep. Corelli’s last performance was in 1975. Corelli left so many wonderful recordings, both live and studio, that it’s almost impossible to pick one to illustrate his art. Probably one of the best is his Pollione, from Norma, which he recorded in 1960 with Maria Callas and Christa Ludwig – one of the greatest Normas ever. Here is the aria Meco all'altar di Venere from Act I. Tullio Serafin conducts the La Scala Orchestra.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: April 12, 2021. Karajan, Part II. Last week we paused our Karajan story somewhere around 1946. At the end of the war Herbert von Karajan, a member of the Nazi party from 1933 and Goering’s favorite, fled to Italy – with the help of the wonderful Italian conductor Victor de Sabata; he then returned to Austria to face the denazification commission and was cleared of any Nazi-related wrongdoings – this time with the help of his father-in law, whose daughter he would divorce soon after. In 1946 he met Walter Legge, the famous record producer and the founder of London’s Philharmonia Orchestra, with which Karajan started a very fruitful relationship. During that time, he also worked with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra (and sometimes with the Vienna Philharmonic), conducted at La Scala and made conducting appearances at the Bayreuth festivals. In 1955 he achieved a pinnacle (if not the pinnacle) of any conductor’s career: he succeeded Wilhelm Furtwängler as the chief conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. But not everybody forgave Karajan’s past: when he took the Berlin Philharmonic on the first tour of the US, he was met with protests, his concert in Detroit was cancelled and Eugene Ormandy, the music director of the Philadelphia Orchestra, refused to shake his hand. But somehow the rest of the world – and eventually the US as well – forgot about Karajan’s past and fell under his spell. And indeed, Karajan was making wonderful music, there is no doubt about that. His concerts and numerous recording with the Berlin Philharmonic were of the highest order. He was also conducting memorable opera performances at La Scala, Vienna and in Salzburg, where he eventually founded his own Easter Festival. His international tours were immensely popular: when he visited Moscow in 1969, mounted police had to be called to the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory to control the crowd. Karajan had the title of Berlin Philharmonic’s music director for life, and conducted the orchestra till 1989, the last year of his life. In 1984 he had a dispute with the orchestra, when he decided to make Sabine Meyer the principal clarinet. The orchestra refused to accept her, Meyer eventually withdrew her candidacy, but the relationship between Karajan and the orchestra was permanently damaged. It is not at all clear who was right in this dispute, the despotic Karajan or the misogynistic orchestra members: after leaving the orchestra, Meyer embarked on a very successful solo career. After that episode, Karajan worked more often with another great orchestra, the Vienna Philharmonic.

the Nazi party from 1933 and Goering’s favorite, fled to Italy – with the help of the wonderful Italian conductor Victor de Sabata; he then returned to Austria to face the denazification commission and was cleared of any Nazi-related wrongdoings – this time with the help of his father-in law, whose daughter he would divorce soon after. In 1946 he met Walter Legge, the famous record producer and the founder of London’s Philharmonia Orchestra, with which Karajan started a very fruitful relationship. During that time, he also worked with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra (and sometimes with the Vienna Philharmonic), conducted at La Scala and made conducting appearances at the Bayreuth festivals. In 1955 he achieved a pinnacle (if not the pinnacle) of any conductor’s career: he succeeded Wilhelm Furtwängler as the chief conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. But not everybody forgave Karajan’s past: when he took the Berlin Philharmonic on the first tour of the US, he was met with protests, his concert in Detroit was cancelled and Eugene Ormandy, the music director of the Philadelphia Orchestra, refused to shake his hand. But somehow the rest of the world – and eventually the US as well – forgot about Karajan’s past and fell under his spell. And indeed, Karajan was making wonderful music, there is no doubt about that. His concerts and numerous recording with the Berlin Philharmonic were of the highest order. He was also conducting memorable opera performances at La Scala, Vienna and in Salzburg, where he eventually founded his own Easter Festival. His international tours were immensely popular: when he visited Moscow in 1969, mounted police had to be called to the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory to control the crowd. Karajan had the title of Berlin Philharmonic’s music director for life, and conducted the orchestra till 1989, the last year of his life. In 1984 he had a dispute with the orchestra, when he decided to make Sabine Meyer the principal clarinet. The orchestra refused to accept her, Meyer eventually withdrew her candidacy, but the relationship between Karajan and the orchestra was permanently damaged. It is not at all clear who was right in this dispute, the despotic Karajan or the misogynistic orchestra members: after leaving the orchestra, Meyer embarked on a very successful solo career. After that episode, Karajan worked more often with another great orchestra, the Vienna Philharmonic.

In the last years of his life Karajan had many health issues but was stoic about them. He resigned his post in Berlin in August of 1989 and died two months later, on June 16th of 1989. Karajan made hundreds of recordings; it’s impossible to pick one to demonstrate the quality of his musicianship. His Bruckner was highly regarded; here is the first movement of Bruckner’s Symphony no. 5. It was recorded by Herbert von Karajan and his Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in 1975.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: April 5, 2021. Karajan, Part I. Today is the birthday of Herbert von Karajan, one of the greatest conductors of the 20th century. He was born in 1908, in Salzburg. Karajan is a Germanized version of the Greek name Karajannis; Herbert’s great-great-grandfather was born in what’s now Greece (back then the territory was an Ottoman possession) and moved to Vienna in 1767. Karajan’s story presents a problem similar to the one posed by the life of the recently deceased James Levine: how are we to judge – or accept – a tremendous musical talent embodied in a flawed personality. In the case of Levine, it was very credible accusations of sexual abuse of young men. With Karajan it was his membership in the Nazi Party. It appears that Karajan joined the Party twice, first, in April of 1933 while in Salzburg, and then two years later when he was living in Aahen. April 1933 was just months after Nazis came to power in Germany – joining the Nazi Party then was early and damning. Moreover, it has been said that during the Nazi period he always opened his concerts with the "Horst-Wessel-Lied," Nazi’s unofficial anthem. We should contrast this with Wilhelm Furtwängler, the leading conductor of the time. Here’s from Wikipedia: “Furtwängler never joined the Nazi Party. He refused to give the Nazi salute, to conduct the Horst-Wessel-Lied, or to sign his letters with "Heil Hitler", even those he wrote to Hitler.” He also refused to participate in many propaganda activities. Moreover, Furtwängler had helped many of his Jewish musicians to escape prosecution. Nevertheless, because Furtwängler stayed in Germany during the Nazi years, he had to endure a lengthy de-Nazification trial and years later had to suffer the humiliation of a rescinded offer from the Chicago Symphony, when Toscanini, Szell, Horowitz and several other prominent musicians threatened the orchestra with a boycott if Chicago were to hire him. Karajan’s fate was very different: he was examined by the de-Nazification board and immediately cleared of any illegal activities, resuming his international career shortly thereafter. On the other hand, it should be mentioned that in 1942 Karajan married a quarter-Jewish Anita Gütermann, after which he was stripped of many positions (he did keep the directorship at the Staatskapelle, though). The Salzburg Wiki says that after the war Karajan and Gütermann fled to Italy, as he was temporarily banned from performing in Germany and Austria. Karajan pleaded with his father-in-law to help him in his de-Nazification process, which Gütermann apparently did. Karajan’s gratitude didn’t last long, as in the early 1950s he met the young French model Eliette Mouret and divorced Anita.

Salzburg. Karajan is a Germanized version of the Greek name Karajannis; Herbert’s great-great-grandfather was born in what’s now Greece (back then the territory was an Ottoman possession) and moved to Vienna in 1767. Karajan’s story presents a problem similar to the one posed by the life of the recently deceased James Levine: how are we to judge – or accept – a tremendous musical talent embodied in a flawed personality. In the case of Levine, it was very credible accusations of sexual abuse of young men. With Karajan it was his membership in the Nazi Party. It appears that Karajan joined the Party twice, first, in April of 1933 while in Salzburg, and then two years later when he was living in Aahen. April 1933 was just months after Nazis came to power in Germany – joining the Nazi Party then was early and damning. Moreover, it has been said that during the Nazi period he always opened his concerts with the "Horst-Wessel-Lied," Nazi’s unofficial anthem. We should contrast this with Wilhelm Furtwängler, the leading conductor of the time. Here’s from Wikipedia: “Furtwängler never joined the Nazi Party. He refused to give the Nazi salute, to conduct the Horst-Wessel-Lied, or to sign his letters with "Heil Hitler", even those he wrote to Hitler.” He also refused to participate in many propaganda activities. Moreover, Furtwängler had helped many of his Jewish musicians to escape prosecution. Nevertheless, because Furtwängler stayed in Germany during the Nazi years, he had to endure a lengthy de-Nazification trial and years later had to suffer the humiliation of a rescinded offer from the Chicago Symphony, when Toscanini, Szell, Horowitz and several other prominent musicians threatened the orchestra with a boycott if Chicago were to hire him. Karajan’s fate was very different: he was examined by the de-Nazification board and immediately cleared of any illegal activities, resuming his international career shortly thereafter. On the other hand, it should be mentioned that in 1942 Karajan married a quarter-Jewish Anita Gütermann, after which he was stripped of many positions (he did keep the directorship at the Staatskapelle, though). The Salzburg Wiki says that after the war Karajan and Gütermann fled to Italy, as he was temporarily banned from performing in Germany and Austria. Karajan pleaded with his father-in-law to help him in his de-Nazification process, which Gütermann apparently did. Karajan’s gratitude didn’t last long, as in the early 1950s he met the young French model Eliette Mouret and divorced Anita.

Be it as it may, Karajan was a tremendously talented and hardworking conductor. He spent his formative years, 1929 to 1934, as the assistant Kapellmeister at Ulm’s Städtisches Theater. He then moved to Aachen as the youngest ever Generalmusikdirektor. In 1938 he made his debut with the Berlin Philharmonic, and in 1941 he was appointed music director of the Staatskapelle Berlin, where Daniel Barenboim currently occupies the same position. In 1946 he met Walter Legge who had just a year earlier formed the Philharmonia Orchestra in London. Karajan worked with the Philharmonia Orchestra from 1946 till 1960, making a number of notable recordings.

In 1946 Karajan was 38 and had another 43 years to live and conduct, which he would till the very end. We’ll continue with him next week.Permalink

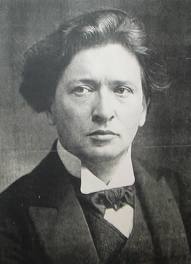

This Week in Classical Music: March 29, 2021. April 1st is a big day for pianists: first of all, it’s the birthday of Sergei Rachmaninov, one of the greatest pianists in history and of course a brilliant composer, who wrote many pieces for his favorite instrument. Rachmaninov’s music, especially his piano concertos no. 2 and 3, is widely played and popular with music listeners. It’s also the birthday of Ferruccio Busoni, also a pianist and composer. As a composer he’s not as famous as Rachmaninov, although his piano transcriptions of the organ works by Bach are part of the standard piano repertoire, but as a pianist he rivaled anybody at the end of the 19th – early 20th century. Busoni was born in 1866, Rachmaninov – in 1873, and these six years, plus the fact that Busoni lived only 58 years make a big difference in their recording legacies: we have a significant number of recordings by Rachmaninov, some of them – recordings of his own works; they are well-known and well-loved. Not so with Busoni: all that is left are several recordings made during one day in February of 1922 at Columbia Studios in London. Their quality is low, the background noise significant, but they are still interesting as historical artefacts. Here is Busoni playing his own transcription of Bach’s organ prelude Nun freut euch, lieben Christen gmein (Rejoice, Beloved Christians) BWV 734. Busoni also made several piano rolls, but those do not authentically represent the pianist’s art. One of the few champions of Busoni’s original compositions is the wonderful pianist Alfred Brendel. Here he is playing, live, Busoni’s Toccata (Preludio - Fantasia – Ciaccona).

especially his piano concertos no. 2 and 3, is widely played and popular with music listeners. It’s also the birthday of Ferruccio Busoni, also a pianist and composer. As a composer he’s not as famous as Rachmaninov, although his piano transcriptions of the organ works by Bach are part of the standard piano repertoire, but as a pianist he rivaled anybody at the end of the 19th – early 20th century. Busoni was born in 1866, Rachmaninov – in 1873, and these six years, plus the fact that Busoni lived only 58 years make a big difference in their recording legacies: we have a significant number of recordings by Rachmaninov, some of them – recordings of his own works; they are well-known and well-loved. Not so with Busoni: all that is left are several recordings made during one day in February of 1922 at Columbia Studios in London. Their quality is low, the background noise significant, but they are still interesting as historical artefacts. Here is Busoni playing his own transcription of Bach’s organ prelude Nun freut euch, lieben Christen gmein (Rejoice, Beloved Christians) BWV 734. Busoni also made several piano rolls, but those do not authentically represent the pianist’s art. One of the few champions of Busoni’s original compositions is the wonderful pianist Alfred Brendel. Here he is playing, live, Busoni’s Toccata (Preludio - Fantasia – Ciaccona).

Dinu Lipatti, a great Romanian pianist, was also born on April 1st, in 1917. We wrote about him two years ago, here. In that entry there’s also more information about Rachmaninov the pianist. There is also a bit about Vladimir Krainev, a wonderful Soviet pianist, who was born on April 1st of 1944. Here are Schumann’s Symphonic Etudes, recorded by Krainev live in 1974. Busoni had many pupils, Egon Petri and Percy Granger among them. Krainev was also a prominent teacher. In 1994, during an economically difficult period in Russia, he organized a foundation to help young musicians. The foundation has grown and now has affiliates in several countries. He also organized the Krainev Young Pianists Competition which has helped to promote careers of dozens of young pianists.

Franz Joseph Haydn was also born this week, on March 31st of 1732. We love him and have written about him many times. And Alessandro Stradella, whose biography is almost as unusual that of Carlo Gesualdo was born on April 3rd of 1639.Permalink

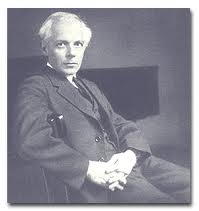

This Week in Classical Music: March 22, 2021. Bartók and much more. Béla Bartók’s 140th birthday is on March 25th. Bartók was one of the most brilliant composers of the 20th century, and we feel that these days he is not being played as often as he should be. Maybe it’s a temporary problem: even though his music is tonal in general terms, it may be too pungent for the Covid era. We’ve written about Bartók many times, for example here, here and here. A much more difficult, but also superb composer was born on March 26th of 1925: Pierre Boulez. There has been much public debating about the music of Boulez and other rigorously atonal and serialist composers such as Charles Wuorinen and Milton Babbitt. The young American composer and conductor, Matthew Aucoin wrote a scathing article in the NY Review of Books called Sound and Fury (very much worth reading). William Bolcom, who is 82, responded gently in Remembering Boulez. This debate is not going away.

and we feel that these days he is not being played as often as he should be. Maybe it’s a temporary problem: even though his music is tonal in general terms, it may be too pungent for the Covid era. We’ve written about Bartók many times, for example here, here and here. A much more difficult, but also superb composer was born on March 26th of 1925: Pierre Boulez. There has been much public debating about the music of Boulez and other rigorously atonal and serialist composers such as Charles Wuorinen and Milton Babbitt. The young American composer and conductor, Matthew Aucoin wrote a scathing article in the NY Review of Books called Sound and Fury (very much worth reading). William Bolcom, who is 82, responded gently in Remembering Boulez. This debate is not going away.

A very different composer, Johann Adolph Hasse was born on March 25th of 1699 near Hamburg. A German, he was instrumental in developing the Italian Opera Seria. Hasse stands as one of the great opera composer of the early 18th century, on par with Alessandro Scarlatti and Antonio Caldara of the generation before him, and George Frideric Handel, Nicola Porpora, Antionio Vivaldi and Leonardo Vinci, with whom he competed directly. Here’s a lovely aria from Hasse’s 1742 opera Didona Abbandonata on the libretto of his friend Metastasio. The countertenor is Valer Barna-Sabadus. Hofkapelle München is conducted by Michael Hofstetter.

Franz Schreker is another opera composer who was very popular during his lifetime but who disappeared practically without a trace soon after. Here is what we’ve written about him a couple years ago. And that year, as this one, the pianist Egon Petri had his anniversary during the same week. Like Bartók, he was born in 1881 and would be 140 on March 23rd.

Speaking of pianists: Byron Janis will turn 92 on March 24th. At the age of eight he became Vladimir Horowitz’s very first pupil. Janis played his debut concert at the Carnegie Hall in 1948 and instantly became one of the stars of his generation; he performed with all major orchestras and played at many major halls worldwide. In 1960, two years after Van Cliburn had won the first Tchaikovsky competition, Janis toured the Soviet Union with spectacular success. In 1973 he developed arthritis which brought his brilliant career to a halt. Here’s Byron Janis playing Rachmaninov’s Prelude in E-Flat Major, Op. 23, No. 6

And then there are two моrе eminent pianists, Wilhelm Backhaus and Rudolf Serkin. Backhaus was born on March 26th of 1884 in Leipzig, Serkin – on March 28th of 1903 in Eger, a town in Bohemia now called Cheb. Both immensely talented, both great interpreters of the music of Beethoven, both native German speakers, both spent a lot of time in the US, but it’s hard to imagine more different biographies. Backhaus was close to the Nazis and knew Hitler personally, though eventually he emigrated from Nazi Germany to Switzerland. Serkin, of Russian-Jewish decent, lived in Vienna and then in Berlin, but after the rise of Nazism had to flee Germany first to Switzerland then to the US.

Last but not least, Mstislav Rostropovich. The great cellist was born on March 27th of 1927. Permalink

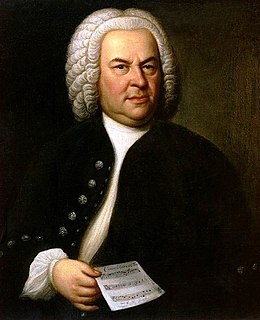

This Week in Classical Music: March 15, 2021. Bach and more. We encounter this problem several times a year: a towering figure was born the week we’re covering; we feel that it would be impossible not to write about him (it’s invariably “him”) and in doing so we miss all other very interesting musicians who were also born around this time. Johann Sebastian Bach’s birthday is on March 21st (he was born in 1685). Bach wrote a cantata a week for several years in a row; we feel that we could write an entry a week for several years, covering his life and music. But we’re trying to achieve a modicum of balance, so at the moment we’ll just play the very first cantata Bach composed as Thomaskantor in Leipzig in 1725 (fortunately, Bach was in the repertoire of other musicians we celebrate today). The cantata Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern (How beautifully the morning star shines) has the BWV number of 1. Of course, it is not his first opus: Bach was 40 by then and had written a lot of music during his years in Weimar and Köthen (for example, the first volume of The Well-Tempered Clavier was composed in 1722). So here’s Cantata BWV 1, performed by the Bach-Ensemble under the direction of Helmuth Rilling.

impossible not to write about him (it’s invariably “him”) and in doing so we miss all other very interesting musicians who were also born around this time. Johann Sebastian Bach’s birthday is on March 21st (he was born in 1685). Bach wrote a cantata a week for several years in a row; we feel that we could write an entry a week for several years, covering his life and music. But we’re trying to achieve a modicum of balance, so at the moment we’ll just play the very first cantata Bach composed as Thomaskantor in Leipzig in 1725 (fortunately, Bach was in the repertoire of other musicians we celebrate today). The cantata Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern (How beautifully the morning star shines) has the BWV number of 1. Of course, it is not his first opus: Bach was 40 by then and had written a lot of music during his years in Weimar and Köthen (for example, the first volume of The Well-Tempered Clavier was composed in 1722). So here’s Cantata BWV 1, performed by the Bach-Ensemble under the direction of Helmuth Rilling.

March 21st also marks the 100th anniversary of Arthur Grumiaux, one of the greatest violinists of the 20th century. He was born in Villers-Perwin, not far from Charleroi, Belgium. At the age of 12 he went to the Brussels Conservatory. He made his debut right before the Germans invaded the country early in WWII. During the occupation he didn’t perform publicly; instead, he played in a private quartet. He resumed his career once the war was over, debuting in London in 1945 and later performing in the US. Grumiaux had a wide repertoire; his Mozart and Beethoven were highly praised; in Mozart he was often accompanied by Clara Haskil. He was especially good in Bach’s unaccompanied violin sonatas. Here, to celebrate both Bach and Grumiaux, is Bach’s Violin Sonata no. 1. The recording was made in Berlin in November of 1960.

Also on March 21st, in 1914, Paul Tortelier, a wonderful French cellist was born. His Bach was masterful: here is Bach Cello Suite No 2 in D minor, performed by Tortelier in 1982.

Finally, Sviatoslav Richter was born on March 20th of 1915. He was by far the most celebrated Soviet pianist with an incredibly broad repertoire. He was enigmatic, brooding, and full of idiosyncrasies. He was also gay, which made his position in the Soviet society especially uncomfortable. And he was a pianist of genius. His Schumann, Prokofiev, Rachmaninov, Beethoven were incomparable. And so were his interpretations of dozens of other composers: he once said that he could play 80 different solo programs. Here is his Bach: French Overture in B Minor. It was made late in Richter’s life, in 1991.Permalink