Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

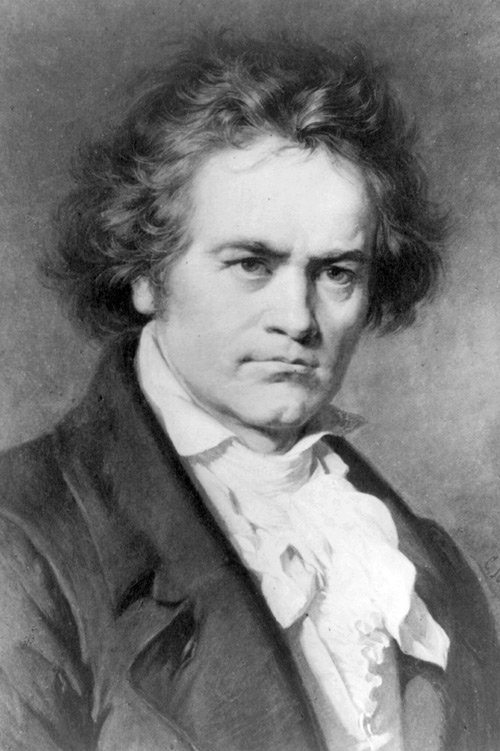

This Week in Classical Music: December 13, 2020. Beethoven 250. The week has arrived, and the day is coming: the whole world will celebrate Beethoven’s 250th on December 16th. All the superlatives aside, it’s impossible to underestimate the significance of Beethoven’s music. One’s personal preferences may go to any other composer, from Bach to Mozart to Chopin and on, but very few people would argue that there was a more important composer in the history of the Western musical canon. We have only two things to add to the uniquely appropriate chorus of praises. One is this: very often, listening to and reading about the “pre-Beethoven” music, we find that in its development it is trailing behind other arts. Take, for the example, the greats of the musical Renaissance, Palestrina, Lasso and Victoria. Their creative years fall somewhere between 1550 and 1600. This is about 80 - 100 years behind the art of paining: Piero della Francesca created his magnificent Stories of the True Cross in the late 1450s, which is the time Andrea Mantegna painted some of his best work. Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus was done in the mid-1480s, as were many of Leonardo’s masterpieces. The flowering of musical Renaissance came at a time when architecture was already well into the Baroque and so was painting, having already transitioned to the Mannerist period. This changed with Beethoven who emphatically brought music into the new era. His music sounded revolutionary during his time, and it sounds fresh today (even the most overplayed pieces, when played well). And once pushed, music stayed that way ever since: you cannot say that Klimt was ahead of Mahler or Picasso ahead of Stravinsky; if anything, music became one of the most “advanced” arts, many would say to its detriment.

superlatives aside, it’s impossible to underestimate the significance of Beethoven’s music. One’s personal preferences may go to any other composer, from Bach to Mozart to Chopin and on, but very few people would argue that there was a more important composer in the history of the Western musical canon. We have only two things to add to the uniquely appropriate chorus of praises. One is this: very often, listening to and reading about the “pre-Beethoven” music, we find that in its development it is trailing behind other arts. Take, for the example, the greats of the musical Renaissance, Palestrina, Lasso and Victoria. Their creative years fall somewhere between 1550 and 1600. This is about 80 - 100 years behind the art of paining: Piero della Francesca created his magnificent Stories of the True Cross in the late 1450s, which is the time Andrea Mantegna painted some of his best work. Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus was done in the mid-1480s, as were many of Leonardo’s masterpieces. The flowering of musical Renaissance came at a time when architecture was already well into the Baroque and so was painting, having already transitioned to the Mannerist period. This changed with Beethoven who emphatically brought music into the new era. His music sounded revolutionary during his time, and it sounds fresh today (even the most overplayed pieces, when played well). And once pushed, music stayed that way ever since: you cannot say that Klimt was ahead of Mahler or Picasso ahead of Stravinsky; if anything, music became one of the most “advanced” arts, many would say to its detriment.

Our second point is that it is Beethoven who serves as the touchstone for all performers. Wilhelm Furtwängler’s repertoire was broad, but he became known as one of the greatest conductors of the 20th century because of his Beethoven. How many times have we all heard Beethoven’s Fifth? And still, when you hear it, for example, in Furtwängler’s mesmerizing performance from 1943 (just to think of the timing of it!) the effect is enormous. Beethoven is central to all major conductors, but of course not just to them: what pianist worthy of the name wouldn’t have many, if not all, of Beethoven’s sonatas in his or her repertoire? Even such an idiosyncratic performer as Glenn Gould recorded most of Beethoven’s sonatas. The same is true of violinist and chamber ensembles.

We mentioned last week that this year was supposed to be the Year of Beethoven. Instead, it became the Year of Covid – a terrible disease dominating great music. We know full well that one of them is temporary… Happy birthday, Beethoven!Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: December 7, 2020. Musings. If it were a normal year, we would be writing about Pietro Mascagni, or Jean Sibelius, or Cesar Franck, or, very likely, about Hector Berlioz, all of whom were born this week. Or, if we had felt that we’d done justice to these wonderful composers in our earlier posts, we might have written about the less popular ones, like the Polish-Russian composer Moise Weinberg, or the great American Modernist Elliott Carter. And we would most likely mention one of our favorites, Olivier Messiaen. This is a big week, but times are by no means normal, so we’ll divert and address other issues. First of all, Covid, which decimated the musical scene. Who could have imagined in February of this year, that the pandemic would close all our concert halls and opera theaters not for a couple of months, but for at least a year and probably much longer? The effects of Covid are devastating: musicians lost their jobs, the lucky ones kept their salaries, often reduced, but most did not. Young performers were hit the worst; not yet established, without a following or financial institutional support, they attempted to continue online only to learn that this is a poor substitute. Music lovers were also hurt, but at least they could revert to their CD collections, classical music radio stations or streaming sites. This was supposed to be the Year of Beethoven, whose 250th anniversary the world will celebrate one week from today, but that was not to be: Covid ruined all of the planned festivals and music series. This is very unfortunate: even though Beethoven’s music is being played all the time, much of it is the same, while some of his pieces are performed less often; those could’ve been showcased this year by the best and most imaginative musicians. And, to state the obvious, Beethoven was a giant – there was music before him, then there were his 30 creative years, and then a whole new period was started, forever affected by his genius.

Hector Berlioz, all of whom were born this week. Or, if we had felt that we’d done justice to these wonderful composers in our earlier posts, we might have written about the less popular ones, like the Polish-Russian composer Moise Weinberg, or the great American Modernist Elliott Carter. And we would most likely mention one of our favorites, Olivier Messiaen. This is a big week, but times are by no means normal, so we’ll divert and address other issues. First of all, Covid, which decimated the musical scene. Who could have imagined in February of this year, that the pandemic would close all our concert halls and opera theaters not for a couple of months, but for at least a year and probably much longer? The effects of Covid are devastating: musicians lost their jobs, the lucky ones kept their salaries, often reduced, but most did not. Young performers were hit the worst; not yet established, without a following or financial institutional support, they attempted to continue online only to learn that this is a poor substitute. Music lovers were also hurt, but at least they could revert to their CD collections, classical music radio stations or streaming sites. This was supposed to be the Year of Beethoven, whose 250th anniversary the world will celebrate one week from today, but that was not to be: Covid ruined all of the planned festivals and music series. This is very unfortunate: even though Beethoven’s music is being played all the time, much of it is the same, while some of his pieces are performed less often; those could’ve been showcased this year by the best and most imaginative musicians. And, to state the obvious, Beethoven was a giant – there was music before him, then there were his 30 creative years, and then a whole new period was started, forever affected by his genius.

But Covid and Beethoven are not the only dominant events of this year. During the last several months we’ve also underwent a rapid cultural transformation that afforded much weight to race and gender. This has put classical music in a rather precarious state: it would’ve never occurred to us to mention this before, but now we have to acknowledge that Beethoven was white and male. And so were most of the major figures of classical music, from its beginning in the 15th century when Guillaume Dufay and then Josquin du Pre introduced melody into their masses and motets, making music recognizable to the modern ear; then the greats of the high Renaissance: Palestrina, Lasso and Victoria, and on to Monteverdi, the first of the Baroque composers, the era that also gave us Italian and French opera, the Scarlattis, Purcell, J.S. Bach and Handel and on to the Classical and Romantic period all the way to 2020. The end of the 20th and 21st century is different: never before have we had so many talented female composers: Jennifer Higdon’s name comes to mind, but also Shulamit Ran, Sofia Gubaidulina, Augusta Read Thomas or Ellen Taaffe Zwilich. And of course, there are more, but it doesn’t mean that we hear more of their compositions - it’s the accessible salon music by Cécile Chaminade and minor pieces by Amy Beach and Florence Price that make their way to the airwaves and the Web. Classical music has been culturally diminishing for years, so what will happen to it now? Will this process accelerate, or will it be reborn in some other form? Something is bound to happen as the current state of it is just too precarious and unsustainable.Permalink

Wilhelm Kempff’s 125th anniversary was just five days ago. Kempff was one of the most interesting pianists of the 20th century. He was born on November 25th of 1895 in a small town of Jüterbog, not far from Berlin. His first teacher was his father, a music director to the royal family. Kempff studied the piano and composition at the Berlin Hochschule für Musik (Conservatory) and later took classes in philosophy and music history. Kempff gave his first recital in 1917, when he played, among other pieces, Beethoven’s Hammerklavier Sonata and Brahms’s Variations on a theme of Paganini. For the next three decades he concertized all across Europe, South America and Japan, but it was only in 1954 that he played in London for the first time and his American début had to wait till 1964 when he was already 68. Kempff recorded all piano sonatas by Schubert and Beethoven; he was also well known for his interpretation of the Romantic composers. Kempff was famous for his singing tone and beautiful coloration. He also didn’t like very fast tempos, preferring the more relaxed, “natural” speed. Kempff lived a long life: he still performed in his eighties and died at the age of 95. Here’s a rarely played Schubert piano sonata in E major, D 157; it’s an early piece, composed when Schubert was just 18. Kempff recorded it in 1968.

Wilhelm Kempff’s 125th anniversary was just five days ago. Kempff was one of the most interesting pianists of the 20th century. He was born on November 25th of 1895 in a small town of Jüterbog, not far from Berlin. His first teacher was his father, a music director to the royal family. Kempff studied the piano and composition at the Berlin Hochschule für Musik (Conservatory) and later took classes in philosophy and music history. Kempff gave his first recital in 1917, when he played, among other pieces, Beethoven’s Hammerklavier Sonata and Brahms’s Variations on a theme of Paganini. For the next three decades he concertized all across Europe, South America and Japan, but it was only in 1954 that he played in London for the first time and his American début had to wait till 1964 when he was already 68. Kempff recorded all piano sonatas by Schubert and Beethoven; he was also well known for his interpretation of the Romantic composers. Kempff was famous for his singing tone and beautiful coloration. He also didn’t like very fast tempos, preferring the more relaxed, “natural” speed. Kempff lived a long life: he still performed in his eighties and died at the age of 95. Here’s a rarely played Schubert piano sonata in E major, D 157; it’s an early piece, composed when Schubert was just 18. Kempff recorded it in 1968.

This Week in Classical Music: November 30, 2020. Kempff, Lupu, Callas. Three composers were born this week: the late Baroque Spaniard, Padre Antonio Soler on December 3rd of 1729, Francesco Geminiani, an Italian who was tremendously popular during his life but now is almost totally forgotten (on December 5th of 1687), and Henryk Górecki, a 20th century Polish composer who became very popular with his sacred minimalist pieces (on December 6th of 1933). We’ve written about all three of them (here, about both Soler and Geminiani, and here about Górecki). Today, though, we’d like to remember a name we’ve failed to mention in our recent posts.

The Romanian pianist Radu Lupu, who is considered one of the greatest living musicians, will turn 75 on November 30th. He was born in 1945 in Galați. He studied in Bucharest with Florica Musicescu who had taught another great Romanian pianist, Dinu Lipatti, and then at the Moscow Conservatory with, among other professors, Heinrich Neuhaus, but thinks that he had learned more by listening to other musicians, and not necessarily pianists: “I took some from Furtwängler, Toscanini, everywhere..” he says. Lupu’s repertoire is broad, but like Kempff he excels in Schubert and Beethoven. Here Radu Lupu plays Schubert’s Piano Sonata in A minor, D 845. The sonata was written ten years after D 157, in 1825.

And of course, we cannot forget Maria Callas. She was born on December 2nd of 1923. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: November 23, 2020. Penderecki. When three year ago we published an entry on , the great Polish composer was alive and, as we thought then, well. Penderecki died earlier this year, on March 29th, not of Covid-19, but after a long illness. Our previous entry stopped at 1975 and we mentioned that around that time Penderecki’s music changed in many significant ways: before that he was an exponent of the avant-garde, exploring new sonorities, new instruments and textures, whereas after 1975 he moved to much more traditional, melodic 19-century idiom. It’s interesting to note that the Grove article on Penderecki is divided into “Music up to 1974” and “Music after 1975.” By the mid-1970s Penderecki was spending much of his time in the US, where he held a Yale University residence. This was a life unknown to regular Polish citizens. Despite all the censorship and general lack of freedom, the Polish government recognized the value of Penderecki as a representative of Polish culture (very much as the Nazis did in the 30s with some of their musicians, and as the Soviet Union did, even if not allowing them the same freedoms as the Poles). Penderecki could travel and live abroad; he was even given a manor in Lusławice, outside of Krakow, where he created a beautiful garden and later a music festival. It was during his tenure at Yale that he turned away from the 12-tone music back to the melodically based compositions. The first significant work in this new style was the 1976 Violin Concerto no. 1, written for Isaac Stern (here it is, performed by the violinist Kim Chee-Yun with the National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Katowice, conducted by Antoni Wit,) Also, around that time the Lyric Opera of Chicago commissioned Penderecki an opera to commemorate the US Bicentennial. Even though Penderecki delivered it two years late, Paradise Lost, as the opera became known, was successfully staged in Chicago and a year later, in 1979, in La Scala. He also increasingly turned to arge-scale choral works: Te Deum, written in1978-80, and Polish Requiem, 1980-84. The Lacrimosa part of the Requiem was the first to be composed; it was dedicated to Lech Wałęsa and written to commemorate those killed in the uprising of 1970. Penderecki then expanded it into a full-length Requiem. Here is Lacrimosa with Jadwiga Gadulanka, soprano, and Krzysztof Penderecki conducting the Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Krakow. Another choral piece, Credo, was written in 1998 and received a Grammy award. Penderecki also wrote several symphonies, the last one, no. 8, subtitled "Lieder der Vergänglichkeit" (Songs of Transience) was completed in 2005 and then expanded in 2007. A prolific composer, Penderecki wrote several operas, a large number of vocal and choral music and several violin sonatas and quartets. Very little of his music was written for the piano.

, the great Polish composer was alive and, as we thought then, well. Penderecki died earlier this year, on March 29th, not of Covid-19, but after a long illness. Our previous entry stopped at 1975 and we mentioned that around that time Penderecki’s music changed in many significant ways: before that he was an exponent of the avant-garde, exploring new sonorities, new instruments and textures, whereas after 1975 he moved to much more traditional, melodic 19-century idiom. It’s interesting to note that the Grove article on Penderecki is divided into “Music up to 1974” and “Music after 1975.” By the mid-1970s Penderecki was spending much of his time in the US, where he held a Yale University residence. This was a life unknown to regular Polish citizens. Despite all the censorship and general lack of freedom, the Polish government recognized the value of Penderecki as a representative of Polish culture (very much as the Nazis did in the 30s with some of their musicians, and as the Soviet Union did, even if not allowing them the same freedoms as the Poles). Penderecki could travel and live abroad; he was even given a manor in Lusławice, outside of Krakow, where he created a beautiful garden and later a music festival. It was during his tenure at Yale that he turned away from the 12-tone music back to the melodically based compositions. The first significant work in this new style was the 1976 Violin Concerto no. 1, written for Isaac Stern (here it is, performed by the violinist Kim Chee-Yun with the National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Katowice, conducted by Antoni Wit,) Also, around that time the Lyric Opera of Chicago commissioned Penderecki an opera to commemorate the US Bicentennial. Even though Penderecki delivered it two years late, Paradise Lost, as the opera became known, was successfully staged in Chicago and a year later, in 1979, in La Scala. He also increasingly turned to arge-scale choral works: Te Deum, written in1978-80, and Polish Requiem, 1980-84. The Lacrimosa part of the Requiem was the first to be composed; it was dedicated to Lech Wałęsa and written to commemorate those killed in the uprising of 1970. Penderecki then expanded it into a full-length Requiem. Here is Lacrimosa with Jadwiga Gadulanka, soprano, and Krzysztof Penderecki conducting the Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Krakow. Another choral piece, Credo, was written in 1998 and received a Grammy award. Penderecki also wrote several symphonies, the last one, no. 8, subtitled "Lieder der Vergänglichkeit" (Songs of Transience) was completed in 2005 and then expanded in 2007. A prolific composer, Penderecki wrote several operas, a large number of vocal and choral music and several violin sonatas and quartets. Very little of his music was written for the piano.

Lest we forget: another prominent composer of the 20th century, Alfred Schnittke was also born this week, on November 24th of 1934. And so was Jean-Baptiste Lully, on November 28th of 1632. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: November 16, 2020. Hindemith at 125. Paul Hindemith was born on November 16th of 1895 in Hanau, near Frankfurt. We’ll pick up where we left off four years ago when we wrote about his life until about 1923. He was then living in Frankfurt, already well known both as a composer and a violist (he organized the Amar Quartet where he played the viola), performing in Salzburg and working at the new music Donaueschingen Festival. (A brief note about the festival: it was organized in 1921, it’s the oldest and probably the most prestigious festival of contemporary music in existence, and Hindemith’s music was played there during its first season). Hindemith also got married to an actress and singer named Gertrud Rottenberg; Gertrud came from a prominent Frankfurt family (her grandfather was the mayor of Frankfurt) and was partly Jewish, which affected Hindemith’s life later in the 1930s. In 1927 he was invited to teach at the Berlin Musikhochschule. He soon decided that teaching composition is impossible, and that only the craft of handling music material could be taught. Lacking suitable textbooks, he embarked on leaning Latin and mathematics in order to be able to read old musical manuals. In 1929 Hindemith left the Amar Quartet and founded a string trio with Josef Wolfstahl, who a year later was replaced by Szymon Goldberg, then the concertmaster of the Berlin Philharmonic, and the celebrated cellist Emanuel Feuermann; thus in the early thirties Hindemith was playing in a trio with two Jewish musicians. Hindemith was not a man of the Left, he didn’t share political views of the likes of Bertolt Brecht, Hanns Eisler or Kurt Weill, but when the Nazis came to power in 1933, they nonetheless declared most of Hindemith’s music “cultural Bolshevism.” His trio could no longer perform in Germany, only abroad, and his Jewish colleagues at the Hochschule lost their jobs. Initially, Hindemith thought that this descent into extreme radicalism i was temporary, that another cycle of elections would change everything back to normal – but there were no free elections to come. Hindemith embarked on writing a major composition, the opera Mathis der Maler, for which he wrote his own libretto. The protagonist of the opera is a historical figure, the painter Matthias Grünewald, famous for his incredible Isenheim Altarpiece. In 1934, at Furtwängler’s request, he composed a symphony based on the opera. The premier in Berlin was a huge success, but it only led to more attacks from the Nazis. Hindemith started thinking about emigration; at the same time he asked Furtwängler to intervene with Hitler on his behalf: he wanted Furtwängler to invite Hitler to a composition class of his. Furtwängler did write an open letter in support of Hindemith, it was published in Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, a major newspaper of the day, in November of 1934. The letter was met with more derision from the Nazis, especially the Nazi “theoretician” Alfred Rosenberg and Joseph Goebbels, the propaganda minister. In 1935 Hindemith was invited by the Turkish government to advise them on the musical life of the country. Subsequently, he visited Turkey in 1936 and 1937. The establishment of the Ankara State Conservatory owes much to Hindemith. In 1936 the Nazis announced a total ban on Hindemith’s music. A year later Hindemith resigned from the Berlin Hochschule and traveled to the US for the first time. He emigrated to Switzerland in September of 1938 and in February of 1940 moved to the US.

years ago when we wrote about his life until about 1923. He was then living in Frankfurt, already well known both as a composer and a violist (he organized the Amar Quartet where he played the viola), performing in Salzburg and working at the new music Donaueschingen Festival. (A brief note about the festival: it was organized in 1921, it’s the oldest and probably the most prestigious festival of contemporary music in existence, and Hindemith’s music was played there during its first season). Hindemith also got married to an actress and singer named Gertrud Rottenberg; Gertrud came from a prominent Frankfurt family (her grandfather was the mayor of Frankfurt) and was partly Jewish, which affected Hindemith’s life later in the 1930s. In 1927 he was invited to teach at the Berlin Musikhochschule. He soon decided that teaching composition is impossible, and that only the craft of handling music material could be taught. Lacking suitable textbooks, he embarked on leaning Latin and mathematics in order to be able to read old musical manuals. In 1929 Hindemith left the Amar Quartet and founded a string trio with Josef Wolfstahl, who a year later was replaced by Szymon Goldberg, then the concertmaster of the Berlin Philharmonic, and the celebrated cellist Emanuel Feuermann; thus in the early thirties Hindemith was playing in a trio with two Jewish musicians. Hindemith was not a man of the Left, he didn’t share political views of the likes of Bertolt Brecht, Hanns Eisler or Kurt Weill, but when the Nazis came to power in 1933, they nonetheless declared most of Hindemith’s music “cultural Bolshevism.” His trio could no longer perform in Germany, only abroad, and his Jewish colleagues at the Hochschule lost their jobs. Initially, Hindemith thought that this descent into extreme radicalism i was temporary, that another cycle of elections would change everything back to normal – but there were no free elections to come. Hindemith embarked on writing a major composition, the opera Mathis der Maler, for which he wrote his own libretto. The protagonist of the opera is a historical figure, the painter Matthias Grünewald, famous for his incredible Isenheim Altarpiece. In 1934, at Furtwängler’s request, he composed a symphony based on the opera. The premier in Berlin was a huge success, but it only led to more attacks from the Nazis. Hindemith started thinking about emigration; at the same time he asked Furtwängler to intervene with Hitler on his behalf: he wanted Furtwängler to invite Hitler to a composition class of his. Furtwängler did write an open letter in support of Hindemith, it was published in Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, a major newspaper of the day, in November of 1934. The letter was met with more derision from the Nazis, especially the Nazi “theoretician” Alfred Rosenberg and Joseph Goebbels, the propaganda minister. In 1935 Hindemith was invited by the Turkish government to advise them on the musical life of the country. Subsequently, he visited Turkey in 1936 and 1937. The establishment of the Ankara State Conservatory owes much to Hindemith. In 1936 the Nazis announced a total ban on Hindemith’s music. A year later Hindemith resigned from the Berlin Hochschule and traveled to the US for the first time. He emigrated to Switzerland in September of 1938 and in February of 1940 moved to the US.

Here’s Hindemith’s Symphony Mathis der Maler, performed by London Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Jascha Horenstein.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: November 9, 2020. Couperin and Borodin. François Couperin, the great French composer, harpsichordist and organist of the Baroque era, was born in Paris on November 10th of 1668. He was a member of an incredible musical dynasty, which flourished from the late 16th century to the mid-19th, or more than 250 years. His family came from Chaumes-en-Brie, a town in the Brie region famous for its cheese, and that’s where several generations of Couperins were born, even though all of them would then move to work in Paris; François was the first one to be born in Paris (there was at least one other, older, composer François Couperin, so to distinguish them, in France “our” Couperin is called Le Grand (the Great). Probably the most famous of François’s ancestors was Louis Couperin, born in 1626, who was also a viol and keyboard player. He was presented to the court of the young Louis XIV and was the first one to be appointed the organist at the church of St. Gervais; eight members of the Couperin family served as organists there, including François Le Grand, the last one serving till 1826. You can read more about François Couperin here.

Paris on November 10th of 1668. He was a member of an incredible musical dynasty, which flourished from the late 16th century to the mid-19th, or more than 250 years. His family came from Chaumes-en-Brie, a town in the Brie region famous for its cheese, and that’s where several generations of Couperins were born, even though all of them would then move to work in Paris; François was the first one to be born in Paris (there was at least one other, older, composer François Couperin, so to distinguish them, in France “our” Couperin is called Le Grand (the Great). Probably the most famous of François’s ancestors was Louis Couperin, born in 1626, who was also a viol and keyboard player. He was presented to the court of the young Louis XIV and was the first one to be appointed the organist at the church of St. Gervais; eight members of the Couperin family served as organists there, including François Le Grand, the last one serving till 1826. You can read more about François Couperin here.

A fine Russian composer Alexander Borodin was born on November 12th of 1833. If he were less of a chemist and more of a composer, we might have enjoyed more of his music, but even as an occasional composer he created a masterpiece, the opera Prince Igor though he left it unfinished (Rimsky-Korsakov and Glazunov completed the orchestration). His symphonies, especially Symphony no 2, and the symphonic piece In the Steppes of Central Asia are fine works and so are his many art songs and some piano pieces. Here’s more about this unusual composer. Also, Aaron Copland, one of the most significant American composers of the 20th century was born 120 years ago, on November 14th of 1900 in Brooklyn, New York.

Two Russian string players were born on November 14th: the violinist Leonid Kogan in 1924 and the cellist Natalia Gutman in 1942. Kogan is rightly considered one of the greatest violinists of the 20th century. He was born in Dnepropetrovsk (now Dnipro, Ukraine) into a Jewish family. He moved to Moscow to study with the famed violin teacher Abram Yampolsky. Kogan started widely performing at the age of 17. In 1951 he won the Queen Elizabeth Competition. In 1955 Leonid Kogan made his debuts in Paris and London and in 1957 – in the US. He has taught at the Moscow Conservatory since 1952. In the 1950s Kogan, Emil Gilels and Mstislav Rostropovich formed a very successful trio (Kogan and Gilels collaborated often, and Kogan married Emil’s sister, Elisaveta). Here’s the recording of Bach’s Chaconne from Partita no.2 in D minor BWV 1004 made live in 1954.

Natalia Gutman was born in Kazan, Russia. At the Moscow Conservatory she studied with Galina Kozolupova and Mstislav Rostropovich. She and her husband, the violinist Oleg Kagan, were friends with Sviatoslav Richter; they played together in many concerts.Permalink