Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

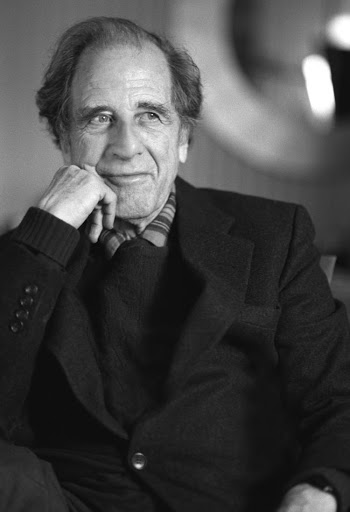

This Week in Classical Music: August 10, 2020. Foss and the pianists. The German-American composer Lukas Foss was born in Berlin on August 15th of 1922. Unusually gifted musically, he started composing at the age of seven. The Fosses, who were Jewish, emigrated from Germany in 1933 when the Nazis came to power. They first went to Paris where Lukas studied with several prominent musicians, then in 1937 they moved to the US. Lukas continued his studies at the Curtis Institute where he met Leonard Bernstein; they became lifelong friends. In 1944, Foss gained prominence with his cantata The Prairie on Carl Sandburg’s poem. A year later, when he was 23 years old, Foss became the youngest recipient of the Guggenheim Fellowship. In 1953 Foss was appointed Professor of Music at UCLA, the position previously occupied by Arnold Schoenberg. He created the Improvisation Chamber Ensemble, directed the Ojai Festival, went on to direct the Buffalo Philharmonic and founded the Center for Creative and Performing Arts in that city. He led and guest conducted a number of orchestras in the US and in Europe and incessantly promoted contemporary music.

musically, he started composing at the age of seven. The Fosses, who were Jewish, emigrated from Germany in 1933 when the Nazis came to power. They first went to Paris where Lukas studied with several prominent musicians, then in 1937 they moved to the US. Lukas continued his studies at the Curtis Institute where he met Leonard Bernstein; they became lifelong friends. In 1944, Foss gained prominence with his cantata The Prairie on Carl Sandburg’s poem. A year later, when he was 23 years old, Foss became the youngest recipient of the Guggenheim Fellowship. In 1953 Foss was appointed Professor of Music at UCLA, the position previously occupied by Arnold Schoenberg. He created the Improvisation Chamber Ensemble, directed the Ojai Festival, went on to direct the Buffalo Philharmonic and founded the Center for Creative and Performing Arts in that city. He led and guest conducted a number of orchestras in the US and in Europe and incessantly promoted contemporary music.

Lukas Foss’s early compositions were neo-classical and often populist, as in this Early Song from Three American Pieces, 1944 (the solo violin is by Itzhak Perlman, with Seiji Ozawa conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra). Later he turned to serialism and improvisation: here is his Elytres for 2 flutes and chamber orchestra from that period, composed in 1964. The New York Philomusica Chamber Ensemble is directed by the composer. Later Foss turned to electronic music. Here is his wonderfully whimsical take on Bach’s Partita in E for solo violin. Leonard Bernstein conducts the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. And here is the interview Lukas Foss gave to Bruce Duffie in 1987.

Two brilliant pianists were also born this week, Aldo Ciccolini on August 15th of 1925 and Julius Katchen, who was born on the same day one year later, in 1926 (Lukas Foss, by the way, was also a brilliant pianist). Ciccolini, an Italian who became a naturalized French citizen, was famous for his interpretation of piano music of his adopted country (his Debussy was exquisite). Katchen, one of the most interesting American pianists of his generation, was a renowned interpreter of the music of Brahms. Katchen died of cancer at the age of 42. We’ll write more about both of these wonderful pianists at a later date.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: July 27, 2020. Dufay’s peregrinations. Guillaume Dufay, the great composer of the Early Renaissance, is unique on at least two accounts: one is his position as the most influential composer of his generation, who was acknowledged as such during his time and retained that position for the following half-millennium. Another is a curiosity: Dufay is one of the very few musicians born in the 14th century whose birthday was “reconstructed” with some certainty. It was done by the musicologist Alejandro Planchart, the foremost scholar of Dufay and his time, who established the date based on the time of Dufay’s ordination, his years as a chorister at Cambrai Cathedral, and events connected with the funding of his obit service. Planchart had determined that Dufay was born on August 5th of 1397 in Beersel, Brabant, not far from Brussels, and moved with his mother to Cambrai, France, soon after. One thing that doesn’t fail to surprise us is the mobility of musicians of the time. We know that in 1420 Dufay went to Rimini where he entered the service of Carlo Malatesta; Rimini is more than 800 miles away from Cambrai, and you have to travel to Geneva, then Turin, Milan and then Bologna in order to get there. After returning to Cambrai, Dufay went to Laon. He then went to Bologna, where he served at the court of Cardinal Louis Aleman. From Bologna Dufay went to Rome, where he served as the papal chaplain. He may have traveled for a brief stay in the Benedictine monastery of Cossonay, near Lausanne. In 1433, Dufay was hired by Duke Amédée VIII of Savoy, and traveled to Chambéry, then the capital of Duchy of Savoy. While in Savoy, Dufay met the composer Gilles Binchois, and the poet and writer on music Martin le Franc, who were working at the court of the Dukes of Burgundy. In 1435 Dufay returned to the papal chapel, which by then moved from Rome to Florence. Two years later, he left the papal employ and returned to Savoy. We know that he went to Lausanne and Basel and two years later entered the service of the Duke of Burgundy. The dukes didn’t have permanent capital and were moving around most of the time, from Dijon to Brussels to Bruges and other cities of the realm, and even though Dufay stayed mainly in Cambrai, we can assume that he also traveled along with the court, at least on some occasions. In the following years Dufay visited other cities, such as Turin, Padua and Mons. Dufay died inCambrai on November 27th of 1474. What makes his travels even more remarkable is that till 1452 the One Hundred Years War was raging between France and England –– and the fighting affected not only France but also Burgundy, making travels that more treacherous.

the most influential composer of his generation, who was acknowledged as such during his time and retained that position for the following half-millennium. Another is a curiosity: Dufay is one of the very few musicians born in the 14th century whose birthday was “reconstructed” with some certainty. It was done by the musicologist Alejandro Planchart, the foremost scholar of Dufay and his time, who established the date based on the time of Dufay’s ordination, his years as a chorister at Cambrai Cathedral, and events connected with the funding of his obit service. Planchart had determined that Dufay was born on August 5th of 1397 in Beersel, Brabant, not far from Brussels, and moved with his mother to Cambrai, France, soon after. One thing that doesn’t fail to surprise us is the mobility of musicians of the time. We know that in 1420 Dufay went to Rimini where he entered the service of Carlo Malatesta; Rimini is more than 800 miles away from Cambrai, and you have to travel to Geneva, then Turin, Milan and then Bologna in order to get there. After returning to Cambrai, Dufay went to Laon. He then went to Bologna, where he served at the court of Cardinal Louis Aleman. From Bologna Dufay went to Rome, where he served as the papal chaplain. He may have traveled for a brief stay in the Benedictine monastery of Cossonay, near Lausanne. In 1433, Dufay was hired by Duke Amédée VIII of Savoy, and traveled to Chambéry, then the capital of Duchy of Savoy. While in Savoy, Dufay met the composer Gilles Binchois, and the poet and writer on music Martin le Franc, who were working at the court of the Dukes of Burgundy. In 1435 Dufay returned to the papal chapel, which by then moved from Rome to Florence. Two years later, he left the papal employ and returned to Savoy. We know that he went to Lausanne and Basel and two years later entered the service of the Duke of Burgundy. The dukes didn’t have permanent capital and were moving around most of the time, from Dijon to Brussels to Bruges and other cities of the realm, and even though Dufay stayed mainly in Cambrai, we can assume that he also traveled along with the court, at least on some occasions. In the following years Dufay visited other cities, such as Turin, Padua and Mons. Dufay died inCambrai on November 27th of 1474. What makes his travels even more remarkable is that till 1452 the One Hundred Years War was raging between France and England –– and the fighting affected not only France but also Burgundy, making travels that more treacherous.

If you want to read more about Dufay and his time, take a look here and here.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: July 27, 2020. Three Tenors. Only two of our tenors were born this week, Sergei Lemeshev and Mario del Monaco, but the birthday of the third one, Giuseppe Di Stefano, was three days ago. The Russian tenor Sergei Lemeshev is the oldest of the three: he was born on this day in 1902. One of the greatest tenors of the Soviet Union, (along with Ivan Kozlovsky) Lemeshev was born into a peasant family. He went to St.-Petersburg to be a shoemaker, listened to gramophone recordings in his free time and learned the musical basics at a vocational school. In 1920 he was sent to the Moscow Conservatory, where he studied for four years, 1921 through 1925. In 1924 he performed the role of Lensky in Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin under the direction of the famed Konstantin Stanislavsky. That was to become his most famous (and favorite) role: he performed it more than 500 times. After graduation he performed in provincial theaters; then in 1931 he was invited to the Bolshoi. With Koslovsky, he became one of Bolshoi’s leading singers for more than a quarter century. He sung numerous roles, many in the operas by Tchaikovsky, Rimsky and other Russian composers, but also the roles of Alfred in La Traviata, Gounod’s Faust, the Duke in Rigoletto and Rodolfo in La Boheme. During WWII he contracted pneumonia and then tuberculosis; he was treated but eventually one of his lungs collapsed. He sang with one lung from 1942 to 1948 when the lung was re-inflated. Lemeshev died in Moscow on June 26th of 1977.

Di Stefano, was three days ago. The Russian tenor Sergei Lemeshev is the oldest of the three: he was born on this day in 1902. One of the greatest tenors of the Soviet Union, (along with Ivan Kozlovsky) Lemeshev was born into a peasant family. He went to St.-Petersburg to be a shoemaker, listened to gramophone recordings in his free time and learned the musical basics at a vocational school. In 1920 he was sent to the Moscow Conservatory, where he studied for four years, 1921 through 1925. In 1924 he performed the role of Lensky in Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin under the direction of the famed Konstantin Stanislavsky. That was to become his most famous (and favorite) role: he performed it more than 500 times. After graduation he performed in provincial theaters; then in 1931 he was invited to the Bolshoi. With Koslovsky, he became one of Bolshoi’s leading singers for more than a quarter century. He sung numerous roles, many in the operas by Tchaikovsky, Rimsky and other Russian composers, but also the roles of Alfred in La Traviata, Gounod’s Faust, the Duke in Rigoletto and Rodolfo in La Boheme. During WWII he contracted pneumonia and then tuberculosis; he was treated but eventually one of his lungs collapsed. He sang with one lung from 1942 to 1948 when the lung was re-inflated. Lemeshev died in Moscow on June 26th of 1977.

Mario del Monaco was born on this day in 1915, Giuseppe Di Stefano – on July 24th of 1921. Both were giants of the Italian opera, and the period in the late 1950s-1960 when both were in their prime – and when Franco Corelli was also at the height of his career – is the golden age of opera, probably never to be repeated. The timber of their voices was different: Di Stefano was a lyric tenor who with time moved to more dramatic roles; it was said that he possessed the most beautiful voice since the time of Beniamino Gigli. He was Pavarotti’s favorite singer. Del Monaco, on the other hand, was a dramatic tenor: his voice was slightly lower than Di Stefano’s but his diapason was large, so he could sing lyric dramatic roles as well: he was great as Radames in Aida and Canio in Pagliacci. Del Monaco had a very exciting voice of enormous power; his most famous role was Otello. Del Monaco’s career was long: he first appeared on stage in 1940 and retired in 1975. Di Stefano, on the other hand, was at the top of his form for just several years in 1950 – but what a voice it was! Here’s Di Stefano in the role of Cavaradossi singing the famous aria E lucevan le stelle from Puccini’s Tosca. This is probably the best Tosca ever recorded: in addition to the phenomenal Di Stefano it featured Maria Callas as Tosca and Titto Gobbi as Scarpia, both at the top of their form. And here’s Mario Del Monaco with the incomparable Renata Tebaldi in the 1952 recording of Gia nella notte densa from Verdi’s Otello.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: July 20, 2020. Stern 100. Tomorrow is the 100th anniversary of Isaac Stern, one of the greatest violinists and cultural figures of the 20th century. Stern was born on July 21st of 1920 in the small town of Kremenets which was then in Poland but is now part of the Ukraine. His family was Jewish, many Jews were leaving the pogrom-ridden lands, and so did the Stern family, just one year after Isaac’s birth. They moved to San Francisco; when Isaac was just eight years old, and he was enrolled in the SF Conservatory. He made his recital début in 1935 and a year later he performed Saint-Saëns’s Violin Concerto no. 3 with the San Francisco Symphony under the direction of Pierre Monteux. Stern made his New York debut in 1937, then played there again, to great acclaim, in 1939, establishing himself as one of the top young violinists. He was the first American violinist to tour the Soviet Union in 1956, in the midst of the cold war. In 1961 Stern created a trio with the pianist Eugene Istomin and the cellist Leonard Rose; they stayed together for the next 23 years, performing widely in the US and Europe, and making many highly acclaimed recordings. Stern also organized a piano quartet with the pianist Emmanuel Ax, the violinist Jaime Laredo and the cellist Yo-Yo Ma. Stern had a very broad repertoire, playing all major violin concertos, all trios of Beethoven and Brahms, and major sonatas. A big supporter of contemporary music, Stern gave first performances of concertos by William Schuman, Krzysztof Penderecki, and Henri Dutilleux, among others.

on July 21st of 1920 in the small town of Kremenets which was then in Poland but is now part of the Ukraine. His family was Jewish, many Jews were leaving the pogrom-ridden lands, and so did the Stern family, just one year after Isaac’s birth. They moved to San Francisco; when Isaac was just eight years old, and he was enrolled in the SF Conservatory. He made his recital début in 1935 and a year later he performed Saint-Saëns’s Violin Concerto no. 3 with the San Francisco Symphony under the direction of Pierre Monteux. Stern made his New York debut in 1937, then played there again, to great acclaim, in 1939, establishing himself as one of the top young violinists. He was the first American violinist to tour the Soviet Union in 1956, in the midst of the cold war. In 1961 Stern created a trio with the pianist Eugene Istomin and the cellist Leonard Rose; they stayed together for the next 23 years, performing widely in the US and Europe, and making many highly acclaimed recordings. Stern also organized a piano quartet with the pianist Emmanuel Ax, the violinist Jaime Laredo and the cellist Yo-Yo Ma. Stern had a very broad repertoire, playing all major violin concertos, all trios of Beethoven and Brahms, and major sonatas. A big supporter of contemporary music, Stern gave first performances of concertos by William Schuman, Krzysztof Penderecki, and Henri Dutilleux, among others.

In 1960 the then owner of Carnegie Hall, a developer named Robert Simon, attempted to sell the building to the New York Philharmonic. The orchestra, which was about to move to the Lincoln Center, decline (one of the reasons being the consideration – in retrospect quite absurd – that New York cannot support two major concert halls). Simon then decided to demolish Carnegie Hall and build an office tower in its place. Isaac Stern organized a group to save it. Under pressure from the group, New York City bought the building from Simon. Carnegie Hall Corporation was established to run the hall and Stern became its president; he stayed in that capacity for the rest of his life. It’s hard to imagine today how close Carnegie Hall, one of the greatest halls acoustically and historically, came to being demolished. In 1964 Stern was instrumental in establishing the National Endowment for the Arts.

Here’s Brahms’s Piano Trio no 1, performed by Isaac Stern, Eugene Istomin and Leonard Rose. This recording was made in 1966.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: July 13, 2020. On Mahler and the Music Scene. Last week we celebrated Gustav Mahler’s 160th anniversary. WFMT, the premier classical music station based in Chicago, also celebrated the event: they played 10 minutes of the Finale of the Symphony no. 4, when Carl Grapentine, their former morning host who now presents “Carl’s Almanac,” short musical introductions, spoke about Mahler for a couple of minutes. Then, at the end of the day, WFMT played "Adagietto," the fourth movement of Symphony no. 5, which, after so much use and misuse turned trite and reminds one more of Luchino Visconti’s film “Death in Venice” rather than Mahler’s symphony. And this is how the same WFMT celebrated Mahler’s 150th anniversary ten years ago: they played all of his symphonies plus Das Lied von der Erde and several song cycles. They played them without interruption, from beginning to end. This was a heroic undertaking: WFMT is a commercial station and they depend on advertising. There is little opportunity to advertise when you run an hour and 40 minutes of Mahler’s Symphony no. 3 straight from the beginning to the end. And still they did it and it was wonderful. Times have changed… But what actually did change? Did music lovers decide that they prefer lighter pieces, and stations like WFMT got the message and adjusted their programming accordingly? Or have listeners found other outlets, like Pandora, Spotify or other Internet streaming services? That would put pressure on commercial radio station, which would try to boost sagging advertising revenues by playing shorter (and often lighter) pieces to squeeze in more ads. We don’t know for sure, maybe services like Nielsen could tell us. We suspect that people still like Mahler. If you go to YouTube, yet another competitor of radio stations, and search for Mahler’s Symphony no. 3, you’ll find that the video recording made in 1973 of Leonard Bernstein conducting the Vienna Philharmonic with Christa Ludwig was watched more than 1.6 million times. It’s likely that not everybody listened to the entire symphony to the end (even though the finale is sublime), but 1.6 million is an amazing number. And that’s just one recording. Cladio Abbado with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra garnered 240,000 views. Semyon Bychkov with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne got another 140,000 views. There are many more recordings of just this one very complex symphony. The easier Mahlerian music, such as his Symphony no. 1, got 2.6 million views (that again from Bernstein and the Vienna Philharmonic). The record holder is probably Gergiev with the so-called Orchestra for Piece, founded in 1995 by Sir Georg Solti: their recording of Mahler’s Symphony no. 5 was watched by four million viewers. So it seems there is no shortage of classical music lovers and outlets to satisfy them. The competition is fearsome and the pressure on classical music radio stations is fierce. We hope they survive, but not by turning away from Mahler.Permalink

4, when Carl Grapentine, their former morning host who now presents “Carl’s Almanac,” short musical introductions, spoke about Mahler for a couple of minutes. Then, at the end of the day, WFMT played "Adagietto," the fourth movement of Symphony no. 5, which, after so much use and misuse turned trite and reminds one more of Luchino Visconti’s film “Death in Venice” rather than Mahler’s symphony. And this is how the same WFMT celebrated Mahler’s 150th anniversary ten years ago: they played all of his symphonies plus Das Lied von der Erde and several song cycles. They played them without interruption, from beginning to end. This was a heroic undertaking: WFMT is a commercial station and they depend on advertising. There is little opportunity to advertise when you run an hour and 40 minutes of Mahler’s Symphony no. 3 straight from the beginning to the end. And still they did it and it was wonderful. Times have changed… But what actually did change? Did music lovers decide that they prefer lighter pieces, and stations like WFMT got the message and adjusted their programming accordingly? Or have listeners found other outlets, like Pandora, Spotify or other Internet streaming services? That would put pressure on commercial radio station, which would try to boost sagging advertising revenues by playing shorter (and often lighter) pieces to squeeze in more ads. We don’t know for sure, maybe services like Nielsen could tell us. We suspect that people still like Mahler. If you go to YouTube, yet another competitor of radio stations, and search for Mahler’s Symphony no. 3, you’ll find that the video recording made in 1973 of Leonard Bernstein conducting the Vienna Philharmonic with Christa Ludwig was watched more than 1.6 million times. It’s likely that not everybody listened to the entire symphony to the end (even though the finale is sublime), but 1.6 million is an amazing number. And that’s just one recording. Cladio Abbado with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra garnered 240,000 views. Semyon Bychkov with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne got another 140,000 views. There are many more recordings of just this one very complex symphony. The easier Mahlerian music, such as his Symphony no. 1, got 2.6 million views (that again from Bernstein and the Vienna Philharmonic). The record holder is probably Gergiev with the so-called Orchestra for Piece, founded in 1995 by Sir Georg Solti: their recording of Mahler’s Symphony no. 5 was watched by four million viewers. So it seems there is no shortage of classical music lovers and outlets to satisfy them. The competition is fearsome and the pressure on classical music radio stations is fierce. We hope they survive, but not by turning away from Mahler.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: July 6, 2020. Mahler at 160. Gustav Mahler, one of the greatest composers in the history of music (Grove Dictionary is more circumspect, calling him “one of the most important figures of European art music in the 20th century,” but we think he was much more than that) was born on July 7th of 1860 in a small town of Kaliště in Moravia (then Kalischt, Austria-Hungary). We’ve been tracing Mahler’s life by his symphonies, the last one, two years ago, being his Symphony no. 6, written in 1903 – 1904. The Seventh followed soon after: Mahler started working on the symphony in 1904 and completed it a year later; he conducted the premiere in Prague in 1908, the work wasn’t well received. By 1904 Mahler’s routine was well established: he would spend music seasons conducting and producing operas at the Hofoper in Vienna and conducting subscription symphonic concerts, and then compose during several summer weeks at his “composing hut” at Maiernigg on lake Wörthersee, near the resort town of Maria Wörth in Carinthia. The summer of 1904 Mahler spent most of the time struggling to complete the Sixth symphony; as for the next one, he only sketched out two Nachtmusik movements (they would become movements two and four once the symphony was completed). The following year, 1905, he was again in trouble. We quote here Mahler’s letter to his wife Alma from an article by the noted Mahler scholar Henry-Louis de La Grange: “I plagued myself for two weeks until I sank into gloom, as you well remember, then I tore off to the Dolomites. There I was led the same dance, and at last gave it up and returned home, convinced that the whole summer was lost. You were not at Krumpendorf [a town on the opposite side of Wörthersee from Maiernigg]to meet me, because I had not let you know the time of my arrival. I got into the boat to be rowed across. At the first stroke of the oars the theme (or rather the rhythm and character) of the introduction to the first movement came into my head—and in four weeks the first, third and fifth movements were done.” This is quite remarkable, as the first movement lasts about 21 minutes, the third – about 10 and the fifth – about 18: Mahler wrote about 50 minutes of very complex symphonic music in just four weeks.

“one of the most important figures of European art music in the 20th century,” but we think he was much more than that) was born on July 7th of 1860 in a small town of Kaliště in Moravia (then Kalischt, Austria-Hungary). We’ve been tracing Mahler’s life by his symphonies, the last one, two years ago, being his Symphony no. 6, written in 1903 – 1904. The Seventh followed soon after: Mahler started working on the symphony in 1904 and completed it a year later; he conducted the premiere in Prague in 1908, the work wasn’t well received. By 1904 Mahler’s routine was well established: he would spend music seasons conducting and producing operas at the Hofoper in Vienna and conducting subscription symphonic concerts, and then compose during several summer weeks at his “composing hut” at Maiernigg on lake Wörthersee, near the resort town of Maria Wörth in Carinthia. The summer of 1904 Mahler spent most of the time struggling to complete the Sixth symphony; as for the next one, he only sketched out two Nachtmusik movements (they would become movements two and four once the symphony was completed). The following year, 1905, he was again in trouble. We quote here Mahler’s letter to his wife Alma from an article by the noted Mahler scholar Henry-Louis de La Grange: “I plagued myself for two weeks until I sank into gloom, as you well remember, then I tore off to the Dolomites. There I was led the same dance, and at last gave it up and returned home, convinced that the whole summer was lost. You were not at Krumpendorf [a town on the opposite side of Wörthersee from Maiernigg]to meet me, because I had not let you know the time of my arrival. I got into the boat to be rowed across. At the first stroke of the oars the theme (or rather the rhythm and character) of the introduction to the first movement came into my head—and in four weeks the first, third and fifth movements were done.” This is quite remarkable, as the first movement lasts about 21 minutes, the third – about 10 and the fifth – about 18: Mahler wrote about 50 minutes of very complex symphonic music in just four weeks.

The years 1904 – 1905 were good to Mahler. He was acknowledged as a great opera conductor, and his symphonic programs with the Philharmonic were popular. Some of his compositions even had critical and popular success (Symphony no. 7 would not go on to be one of them). He lived very comfortably, was happily married, and his second daughter, Anna, was born in 1904. He had many friends and admirers among musicians and developed a special relationship with the Concertgebouw Orchestra and its conductor Willem Mengelberg. Just three years later Mahler would have to leave Hofoper, hounded by antisemitic music critics; in 1907 his first daughter, Maria, would die of scarlet fever and his marriage to Alma would be on the rocks.

Symphony no. 7 consists of five movements, which you could listen to separately Langsam, Allegro, Nachtmusik I, Scherzo, Nachtmusik II, and Rondo-Finale, or to the whole symphony here. Leonard Bernstein conducts the New York Philharmonic in this 1985 recording.Permalink