Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

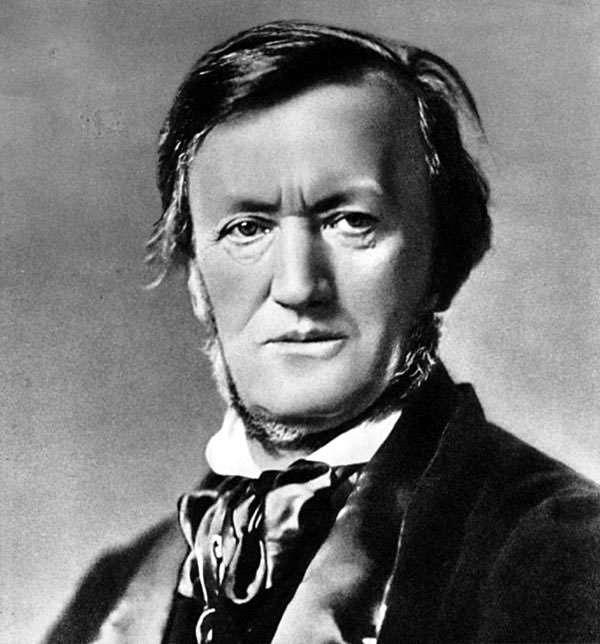

This Week in Classical Music: May 18, 2020. Wagner. Richard Wagner was born on May 22nd of 1813. One of the most important achievements of his life was the establishment of the Bayreuth Festival (or Bayreuther Festspiele in German) in 1876. One of the most important and prestigious music festivals in the world, it ran with few interruptions since then but this year it was cancelled because of the coronavirus. This is a strange time we’re living in.

the Bayreuth Festival (or Bayreuther Festspiele in German) in 1876. One of the most important and prestigious music festivals in the world, it ran with few interruptions since then but this year it was cancelled because of the coronavirus. This is a strange time we’re living in.

Wagner was thinking of establishing a festival to promote his operas since the breakup with his patron of many years, King Ludwig II of Bavaria in 1865, when he had to leave Munich under a cloud. On the advice of his friend, the conductor Hans Richter, Wagner selected Bayreuth, a Bavarian town near Nuremberg as the place for the festival, partly on the assumption that the existing opera house would be an adequate venue. The theater, while beautiful, proved to be insufficient for the enormous productions envisioned by the composer, but the city was supportive and with its help Wagner embarked on the construction of a new theater. The money soon dried up and Wagner went fundraising around Germany. Twice he talked to the Chancellor Bismarck, to no avail. Eventually Wagner was forced to appeal to his former patron, King Ludwig, who, reluctantly, lent Wagner the money. The theater’s cornerstone was laid on May 22nd, 1872, (Wagner's birthday) and the theater was opened to the public in August of 1876; Das Rheingold was performed three nights in a row. The German Kaiser Wilhelm and King Ludwig both attended (on separate nights, as Ludwig was against Bavaria losing its independence within the newly-formed Germany), and so did many luminaries, including Wagner’s father-in-law Franz Liszt, Anton Bruckner, Edvard Grieg, and Tchaikovsky. The opening, while musically highly successful, was a disaster financially, and the second season took place only six years later, in 1882. It was dedicated exclusively to Parsifal, which was written specifically for the Festspielhaus. Wagner himself conducted the final scene of the last performance. He died less than a year later. Since then it’s been the Wagners who have been running the festival. First, Richard’s widow Cosima List Wagner took over, then Siegfried Wagner, Richard and Cosima’s son. Siegfried died in 1930 and his wife, Winifred Wagner became the director. This infamous friend and admirer of Adolph Hitler ran the Bayreuth till 1945. After the war, the festival resumed in 1951 with Wagner’s grandsons Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner at the helm. After Wieland’s death in 1966 his brother continued on his own, till 2008. Wolfgan’s daughters Eva and Katharina Wagner ran the festival together till 2015, and since then Katharina has been running it alone. Let us hope that the hiatus is short and that the 2021 festival will take place as scheduled.

The great Wagnerian soprano Birgit Nilsson was also born this week, on May 17th of 1918.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: May 11, 2020. Bits and pieces. Claudio Monteverdi, a great Italian composer, was born this week, on May 15th of 1567, but we’ve written about him so many times (here, here, here and more) that we will skip the event this time around. Otherwise, several very good but hardly great Frenchmen: Massenet, Fauré and Satie (born on May 12th of 1842, on the same day of 1845 and on May 17th of 1866 respectively), a very nice but underappreciated Czech composer Jan Václav Voříšek was born on May 11th of 1791; he died of tuberculosis at the age of 34, who knows how far his talent would’ve carried him had he lived longer. Then, to quote one of our earlier entries,, “Anatol Liadov, a minor but pleasant composer of short piano pieces. Were it not for his laziness and lack for self-assurance, he might’ve developed into a major talent (Liadov was born on May 12th of 1855).” And we cannot seriously celebrate the birthday of Maria Theresia von Paradis any longer (she was born on May 15th of 1759) because, as it turns out, the only piece of interest, Sicilienne, was written not by her but by the violinist Samuel Dushkin, who arranged the music from the second movement of Carl Maria von Weber’s Violin Sonata op. 10 no. 1 and presented it as her piece.

times (here, here, here and more) that we will skip the event this time around. Otherwise, several very good but hardly great Frenchmen: Massenet, Fauré and Satie (born on May 12th of 1842, on the same day of 1845 and on May 17th of 1866 respectively), a very nice but underappreciated Czech composer Jan Václav Voříšek was born on May 11th of 1791; he died of tuberculosis at the age of 34, who knows how far his talent would’ve carried him had he lived longer. Then, to quote one of our earlier entries,, “Anatol Liadov, a minor but pleasant composer of short piano pieces. Were it not for his laziness and lack for self-assurance, he might’ve developed into a major talent (Liadov was born on May 12th of 1855).” And we cannot seriously celebrate the birthday of Maria Theresia von Paradis any longer (she was born on May 15th of 1759) because, as it turns out, the only piece of interest, Sicilienne, was written not by her but by the violinist Samuel Dushkin, who arranged the music from the second movement of Carl Maria von Weber’s Violin Sonata op. 10 no. 1 and presented it as her piece.

Two prominent conductors were born this week, Carlo Maria Giulini and Otto Klemperer. We wrote about Klemperer not that long ago (here), but never about Giulini. Carlo Maria Giulini was born on May 9th of 1914 in Barletta, in southern Italy. He studied the viola and conducting at the Academy of Santa Cecilia and then played in the Academy’s orchestra. In 1944 he became the orchestra’s conductor, then was hired to lead the orchestra of the Italian Radio. In 1964 he was appointed the principal conductor at La Scala. There he worked closely with Maria Callas and with the directors Luchino Visconti and Franco Zeffirelli. Later he worked with Visconti at Covent Garden, London, where he conducted several operas. During the late 1950s and 1960s Giulini was closely associated with the Philharmonia Orchestra, London. In 1969 he became Principal guest conductor at the Chicago Symphony, and in 1978 – the Chief conductor at the Los Angeles Philharmonic. His performances of Verdi’s Requiem were famous, and so were his staging of Mozart and Verdi operas in Los Angeles and Milan. Giulini died in Brescia (recently an epicenter of one of the major coronavirus outbreaks in Italy) on June 14th of 2005.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: May 4, 2020. Tchaikovsky and more. This is one of these weeks when we don’t even know where to start: half a dozen composes, two pianists and three conductors all born within the next 7 days. We’ll have to start with Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: May 7th marks the 180th anniversary of his birthday. If you sense some reluctance on our part, you may be right. Don’t get us wrong: we consider Tchaikovsky a major talent, the most important Russian composer of the second half of the 19th century who influenced many, among them Igor Stravinsky. His Piano concerto in B-flat minor (no. 1), the Violin concerto; his last three symphonies, from no. 4 to no. 6; operas like “Eugene Onegin” and “The Queen of Spades” and some other pieces are of the highest quality. And he cuts a sympathetic figure: a homosexual in a conservative Russian society who attempted to marry to please his family – with disastrous results; a wanderer, who spend many years in Europe; a social recluse, who had an unusual relationship with his major benefactor, Nadezhda von Meck, whom he never met; his many personal traumas; his death of cholera at the age of only 53 which many think was a suicide – all this endears us to Tchaikovsky. So what of our hesitancy? It has nothing to do with a lot of mediocre music Tchaikovsky had written (like his 2nd and 3rd Piano concertos, or many operas, or much of the ballet music) – not a single composer, Mozart including, had written music on the highest level all the time - we value composers for their best piece, not judge them on their worst. No, the problem – and if there is one, it’s probably with our perception, not with Tchaikovsky – is with his unusual position vis-à-vis the development of European music. As much as his music is integral to it, he stands apart. Tchaikovsky died in 1893 and was writing till the very end; by then the whole symphonic tradition, originating with Wagner and then brought up by Bruckner and Mahler had been developed (Bruckner’s Symphony no. 4 was premiered in 1881; Mahler’s Symphony no. 1 – in 1889). A very different but highly innovative composer, Claude Debussy was already active for some years (his Suite Bergamasque was composed in 1890). Tchaikovsky seems to be out of step; despite his influence on Rachmaninov and many Russian and Soviet symphonists, it feels like the path he broke doesn’t lead anywhere. Whether it’s true or not, in the end it probably doesn’t matter. Here, to celebrate Tchaikovsky’s 180th, is a brilliant 2nd movement from Tchaikovsky’s last, Sixth Symphony. It was written in a 5/4 tempo: try to “conduct” it yourself while following a recording – it’s really difficult. In this particular case, the real conductor is Sir Georg Solti, leading the very nimble Chicago Symphony orchestra.

conductors all born within the next 7 days. We’ll have to start with Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: May 7th marks the 180th anniversary of his birthday. If you sense some reluctance on our part, you may be right. Don’t get us wrong: we consider Tchaikovsky a major talent, the most important Russian composer of the second half of the 19th century who influenced many, among them Igor Stravinsky. His Piano concerto in B-flat minor (no. 1), the Violin concerto; his last three symphonies, from no. 4 to no. 6; operas like “Eugene Onegin” and “The Queen of Spades” and some other pieces are of the highest quality. And he cuts a sympathetic figure: a homosexual in a conservative Russian society who attempted to marry to please his family – with disastrous results; a wanderer, who spend many years in Europe; a social recluse, who had an unusual relationship with his major benefactor, Nadezhda von Meck, whom he never met; his many personal traumas; his death of cholera at the age of only 53 which many think was a suicide – all this endears us to Tchaikovsky. So what of our hesitancy? It has nothing to do with a lot of mediocre music Tchaikovsky had written (like his 2nd and 3rd Piano concertos, or many operas, or much of the ballet music) – not a single composer, Mozart including, had written music on the highest level all the time - we value composers for their best piece, not judge them on their worst. No, the problem – and if there is one, it’s probably with our perception, not with Tchaikovsky – is with his unusual position vis-à-vis the development of European music. As much as his music is integral to it, he stands apart. Tchaikovsky died in 1893 and was writing till the very end; by then the whole symphonic tradition, originating with Wagner and then brought up by Bruckner and Mahler had been developed (Bruckner’s Symphony no. 4 was premiered in 1881; Mahler’s Symphony no. 1 – in 1889). A very different but highly innovative composer, Claude Debussy was already active for some years (his Suite Bergamasque was composed in 1890). Tchaikovsky seems to be out of step; despite his influence on Rachmaninov and many Russian and Soviet symphonists, it feels like the path he broke doesn’t lead anywhere. Whether it’s true or not, in the end it probably doesn’t matter. Here, to celebrate Tchaikovsky’s 180th, is a brilliant 2nd movement from Tchaikovsky’s last, Sixth Symphony. It was written in a 5/4 tempo: try to “conduct” it yourself while following a recording – it’s really difficult. In this particular case, the real conductor is Sir Georg Solti, leading the very nimble Chicago Symphony orchestra.

Where there is Tchaikovsky, there is Johannes Brahms. They were born on the same day, Brahms in 1833, sever years before Tchaikovsky. And other composers that were also born this week are, in a historical order: Giovanni Paisiello, an Italian and the most popular opera composer of the late 18th century (May 9, 1740); Carl Stamitz (May 8, 1745), the German composer of the Mannheim School fame; Stanislaw Moniuszko, the creator of the Polish national opera (May 5, 1819); Louis Moreau Gottschalk, an American of half-Jewish, half French-Creole descent (May 8, 1829), very popular in his days; and, finally, Milton Babbitt, one of the most interesting American modernist composers of the last century. As for the pianists and conductors, those will have to wait till next year.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: April 27, 2020. Scarlatti père. Alessandro Scarlatti, one of the most interesting opera composers of the Italian Baroque, was born on May 2nd of 1660 in.jpg) Palermo. He’s considered the founder of the Neapolitan school of opera, the school that gave the world such composers as Nicola Porpora, Leonardo Vinci, Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, Niccolò Piccinni, Giovanni Paisiello and Domenico Cimarosa. Scarlatti’s family moved to Rome when he was 10. He married a Roman girl at 18 and then managed to establish connections at the very top of the Roman society: he stayed at the palace of the famous sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini; Cardinal Benedetto Pamphili, a patron of arts and a member of Accademia dell'Arcadia, provided a libretto to several of Scarlatti’s operas and introduced him to the circle of Queen Christina of Sweden (Scarlatti himself would eventually join the prestigious Academy, founded under the patronage of Queen Christina).

Palermo. He’s considered the founder of the Neapolitan school of opera, the school that gave the world such composers as Nicola Porpora, Leonardo Vinci, Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, Niccolò Piccinni, Giovanni Paisiello and Domenico Cimarosa. Scarlatti’s family moved to Rome when he was 10. He married a Roman girl at 18 and then managed to establish connections at the very top of the Roman society: he stayed at the palace of the famous sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini; Cardinal Benedetto Pamphili, a patron of arts and a member of Accademia dell'Arcadia, provided a libretto to several of Scarlatti’s operas and introduced him to the circle of Queen Christina of Sweden (Scarlatti himself would eventually join the prestigious Academy, founded under the patronage of Queen Christina).

The cultural and musical life of Rome at the end of the 17th century was flourishing. This was somewhat of a miracle, as not that long prior, in 1527, Rome was devastated during the catastrophe of the Sack of Rome, when the mutinous troops of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, entered and pillaged the city, killing and raping its inhabitants and plundering everything of value. The troops stayed in the city and continued the plunder for almost eight months, till the food ran out. When they left, the population of Rome was 10,000 – a year earlier it had been 55,000. The Sack of Rome marked the end of the Italian Renaissance, as most artists left Rome and never returned (though the event gave birth to the period called Mannerism). But despite everything, the devastated Rome was rebuilt, Michelangelo completed the design of the great cupola of St. Peter’s Basilica and Carlo Maderna finished its monumental façade in 1612. Baroque changed the face of the city, and Bernini, the sculptor of genius, embellished it as never before. By the end of the 16th century the population of Rome grew to 100,000 and by the time of Scarlatti it was even larger. The popes and the cardinals, despite all the corruption and nepotism, proved to be great patrons of arts; Cardinal Pamphili was one of the most important. His birthday was just two days ago – he was born on April 25th of 1653. We’ve written about Queen Christina and Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni, two great patrons of art – we should write about Benedetto Pamphili as well, he very much deserves it.

Scarlatti’s opera Gli equivoci nel sembiante (“Equivocal Appearances”) was so successful that Queen Christina appointed him her maestro di cappella; at the time Scarlatti was just eighteen. In the following six years, six of his operas were staged in Rome, quite a success for a young composer. But opera came under pressure from the church and the pope: religious authorities considered this art profane, and most operas were staged in private theaters. In 1684 Scarlatti received an offer from the Viceroy of Naples to become his maestro di cappella and left Rome. Here’s the aria Onde, ferro, fiamme e morte (Waves, iron, flames and death) from Gli equivoci nel sembiante. Renata Fusco is the soprano.Permalink

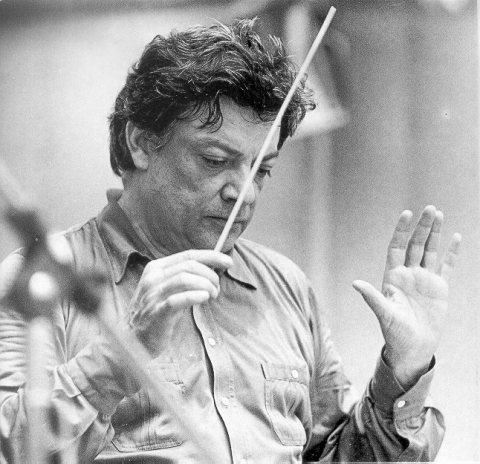

This Week in Classical Music: April 20, 2020. Maderna and more. Tomorrow, on April 21st we’ll celebrate the 100th anniversary of the birth of the Italian composer Bruno Maderna. Maderna, one of the most important avant-garde composers of the 20th century, was born in Venice. A child prodigy, he played the violin and, at the age of 12 conducted the orchestra of La Scala. He was noticed and celebrated by Mussolini’s cultural authorities. In 1941-42 Maderna studied with the eminent composer Gian Francesco Malipiero. Later he studied conducting with Hermann Scherchen, an influential interpreter of the music of Mahler (later in his life Maderna also became a very successful interpreter of Mahler’s music. At the end of the 1940s Maderna got involved with a group of musicians at Darmstadt, among whom were the young Pierre Boulez, Olivier Messiaen, John Cage, Luigi Nono and Karlheinz Stockhausen. Another young Italian composer associated with Maderna was Luciano Berio, with whom he established Studio di fonologia musicale di Radio Milano, which facilitated their research into electonic music. In the 1960s and ‘70s Maderna spent a lot of time in the US, performing with contemporary ensembles but also conducting at established venues like Tanglewood, where he was appointed director of new music and working with major orchestras in New York, Boston and Chicago. Maderna died in Darmstadt on November 13th of 1973 of cancer. Maderna’s music was highly influential, though, like the music of his Darmstadt colleagues, not easy on the first hearing. His output was broad: he composed many symphonic pieces, chamber music and several concertos for different instruments, from the piano to the oboe. Here’s his rather short (less than 12 minutes) concerto for two pianos from the early period: it was written in 1948. It’s performed by the Italian pianists Aldo Orvieto and Fausto Bongelli, with the ensemble “Orchestra Della Fondazione Arena Di Verona,” Carlo Miotto conducting.

Maderna, one of the most important avant-garde composers of the 20th century, was born in Venice. A child prodigy, he played the violin and, at the age of 12 conducted the orchestra of La Scala. He was noticed and celebrated by Mussolini’s cultural authorities. In 1941-42 Maderna studied with the eminent composer Gian Francesco Malipiero. Later he studied conducting with Hermann Scherchen, an influential interpreter of the music of Mahler (later in his life Maderna also became a very successful interpreter of Mahler’s music. At the end of the 1940s Maderna got involved with a group of musicians at Darmstadt, among whom were the young Pierre Boulez, Olivier Messiaen, John Cage, Luigi Nono and Karlheinz Stockhausen. Another young Italian composer associated with Maderna was Luciano Berio, with whom he established Studio di fonologia musicale di Radio Milano, which facilitated their research into electonic music. In the 1960s and ‘70s Maderna spent a lot of time in the US, performing with contemporary ensembles but also conducting at established venues like Tanglewood, where he was appointed director of new music and working with major orchestras in New York, Boston and Chicago. Maderna died in Darmstadt on November 13th of 1973 of cancer. Maderna’s music was highly influential, though, like the music of his Darmstadt colleagues, not easy on the first hearing. His output was broad: he composed many symphonic pieces, chamber music and several concertos for different instruments, from the piano to the oboe. Here’s his rather short (less than 12 minutes) concerto for two pianos from the early period: it was written in 1948. It’s performed by the Italian pianists Aldo Orvieto and Fausto Bongelli, with the ensemble “Orchestra Della Fondazione Arena Di Verona,” Carlo Miotto conducting.

One of the greatest composers of the first half of the 20th century, Sergei Prokofiev was born on April 23 of 1891, though not all sources agree on the date: the English-language Wikipedia says it’s April 27th. Prokofiev himself celebrated his birthday on the 23rd and that’s the date we use. Next year is his 130th anniversary, and we will dedicate a full entry to him.

Yehudi Menuhin, one of the greatest violinists of the 20th century, was born in New York on April 22nd of 1916. Here’s what we wrote about him last year.

And finally, the British conductor John Eliot Gardiner, a brilliant interpreter of the music of Bach, was born on this day in 1943. We have several samples of his work in our library, mostly Bach’s oratorios. In 2000 Gardiner, together with his ensembles, English Baroque Soloists and the Monteverdi Choir, set out on what Gardiner called his Bach Cantata Pilgrimage. For a full year they traveled around Europe and the US performing all Bach’s oratorios: a triumphm, both musically and logistically.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: April 13, 2020. Easter and three pianists. Yesterday was Easter Sunday, the beginning of the Easter Season, and we wish everybody a happy Easter. Around this time we usually play Bach’s music: he wrote some of his greatest pieces for this occasion, such as two complete Passions, the St. John and St. Matthew (his St. Mark’s Passion is lost; it’s assumed by musicologists that it was mostly a “parody,” meaning that Bach recycled some of his previously written music. The St. Luke Passion, previously attributed to Bach, is almost certainly not his own). Bach’s friend Georg Philipp Telemann also wrote a number of Passion Oratorios. They are not well known and aren’t performed as often as Bach’s. While we realize that they are not on the same plane, we find their music much worthy of your attention. Here’s the first section of Telemann’s oratorio Das selige Erwägen des bittern Leidens und Sterbens Jesu Christi (Blessed Contemplation of the Bitter Suffering and Dying of Jesus Christ) – about 20 minutes of music. Ensemble L'arpa festante is conducted by Wolfgang Schäfer.

occasion, such as two complete Passions, the St. John and St. Matthew (his St. Mark’s Passion is lost; it’s assumed by musicologists that it was mostly a “parody,” meaning that Bach recycled some of his previously written music. The St. Luke Passion, previously attributed to Bach, is almost certainly not his own). Bach’s friend Georg Philipp Telemann also wrote a number of Passion Oratorios. They are not well known and aren’t performed as often as Bach’s. While we realize that they are not on the same plane, we find their music much worthy of your attention. Here’s the first section of Telemann’s oratorio Das selige Erwägen des bittern Leidens und Sterbens Jesu Christi (Blessed Contemplation of the Bitter Suffering and Dying of Jesus Christ) – about 20 minutes of music. Ensemble L'arpa festante is conducted by Wolfgang Schäfer.

Artur Schnabel, the great Austrian pianist, was born on April 17th of 1882 in a small town of Lipnik (then Kunzendorf) in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Today the town is in Poland. His family was Jewish: Schnabel’s birth name was Aaron. When he was two, the family moved to Vienna. At the age of nine Schnabel became a pupil of the famous pianist and pedagogue Theodor Leschetizky who later told Schnabel: “You will never be a pianist; you are a musician.” In 1898 Schnabel moved to Berlin. In his youth, his repertoire was very broad: in addition to his beloved Beethoven, he played other German greats - Mozart, Schubert, Schuman and Brahms. But he also played a lot of Chopin, Liszt and other Romantics. He formed a quartet with the violinist Bronisław Huberman, Paul Hindemith, who was not only a composer but also an excellent violist, and the cellist Gregor Piatigorsky. Later in his career Schnabel narrowed his repertoire, concentrating on Schubert and especially Beethoven. In Beethoven he excelled; no pianist before him, and very few after, played Beethoven with such depth. In 1933 Schnabel emigrated from Germany first to England and then, in 1939, to the US. He mother stayed in Vienna and in 1942, at the age of 83, she was deported to Theresienstadt, where she died two months later. Schnabel, who after the war played in many European countries, never returned to either Austria or Germany. Schnabel was the first pianist to record all of Beethoven’s piano sonatas. Even though one can hear some technical flaws, these recording stand out, even all these years later. As Harold Schonberg, the music critic, said of Schnabel, he was "the man who invented Beethoven.”

Two Soviet pianist, both winners of the Tchaikovsky Competition, were also born this week: Grigory Sokolov in Leningrad on April 18th of 1950 and Mikhail Pletnev in Arkhangelsk on April 14th of 1957. Sokolov won the 1966 Tchaikovsky Competition at the age of 16. Pletnev won his in 1978, at 21. Sokolov emigrated to Europe and developed a cult following there; Pletnev stayed in the Soviet Union and made a brilliant career, both as a pianist and conductor.

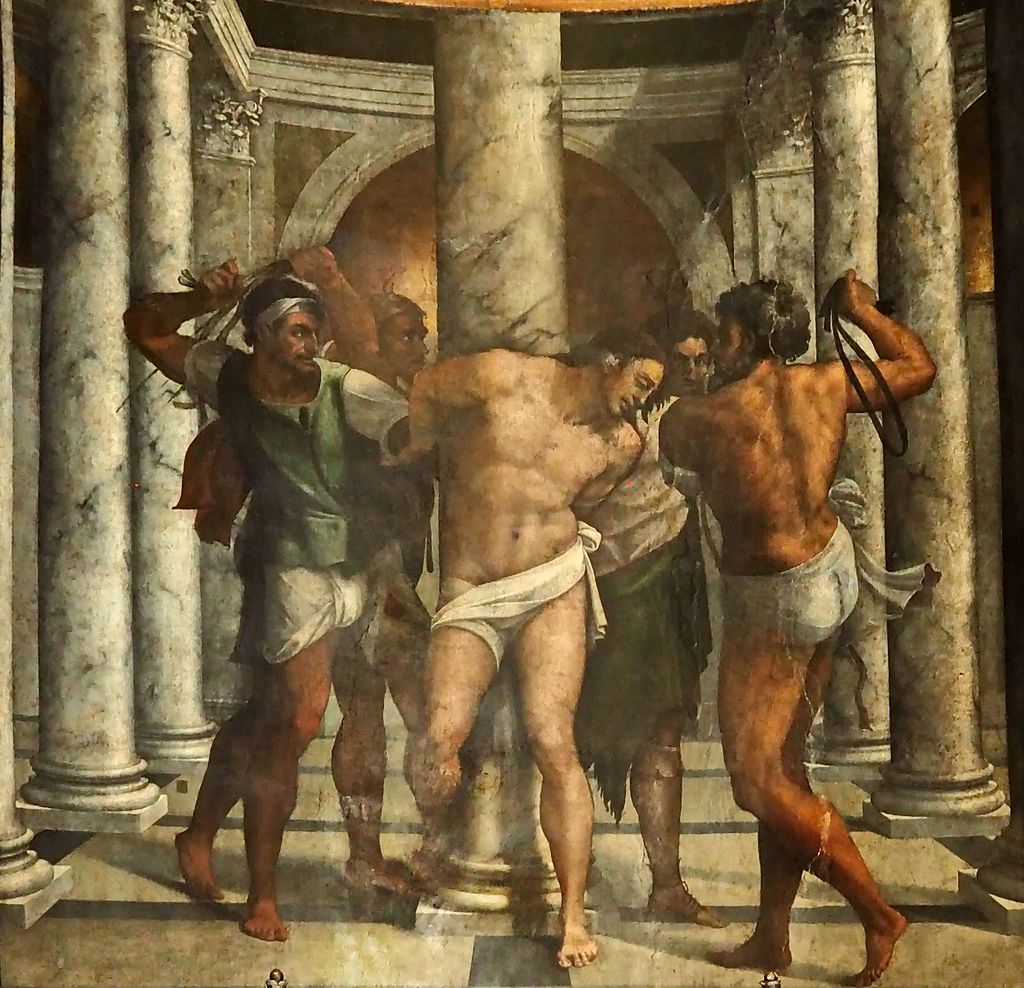

The Flagellation, above, was painted in 1516 by the great Italian, Sebastiano del Piombo; it’s based on a drawing by Michelangelo.Permalink