Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

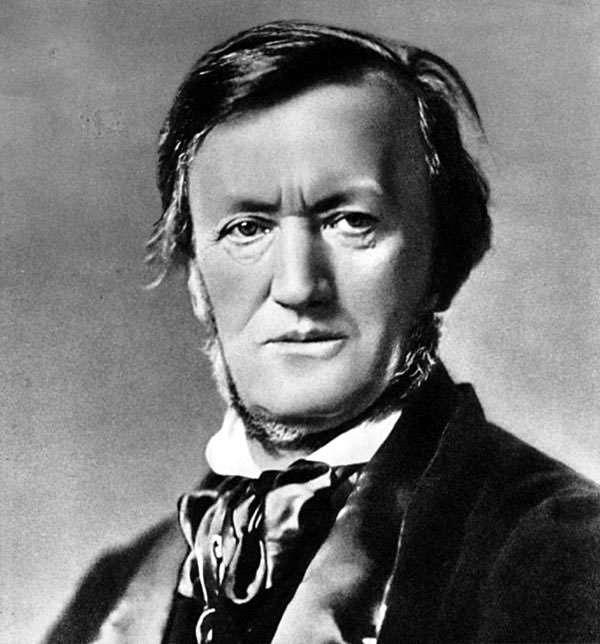

May 22, 2017. Wagner and Francaix. Richard Wagner was born on this day in 1813. For some years we’ve been following Wagner’s life by the milestones of his operas; last year we arrived at the end of the “Romantic operas” period, with Lohengrin, written in 1848 and its premier in 1850, being the last one. Wagner’s genius had matured, and during the next several years he would produce not simply “operas” but “music dramas,” the term Wagner himself used to describe what he considered to be a “total work of art,” art that combines music and theater into one unified whole. He started working on Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung) in 1848 and continued for almost 26 years, completing the composition of the last (fourth) opera of the cycle, Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods) in 1874. During that period, he also wrote two other masterpieces, Tristan und Isolde and Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Wagner intended the Ring to be performed as a cycle, as it was at the premier, in the course of several days in August of 1876 in Bayreuth. The premier took place in a specially built theater, the old opera house being too small for Wagner’s orchestra. Wagner’s old patron, King Ludwig II of Bavaria, even though his relationship with Wagner had soured throughout the years, was instrumental in financing the theater. The premier was attended by royalty (Kaiser Wilhelm was there, as well as Ludwig, and Don Pedro, the Emperor of Brazil). The leading musicians of the day were also present: Anton Bruckner, Edvard Grieg, Tchaikovsky, and of course Franz Liszt, Wagner’s father in law. And so was the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, one of the major influences and, for a while, a good friend.

premier in 1850, being the last one. Wagner’s genius had matured, and during the next several years he would produce not simply “operas” but “music dramas,” the term Wagner himself used to describe what he considered to be a “total work of art,” art that combines music and theater into one unified whole. He started working on Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung) in 1848 and continued for almost 26 years, completing the composition of the last (fourth) opera of the cycle, Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods) in 1874. During that period, he also wrote two other masterpieces, Tristan und Isolde and Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Wagner intended the Ring to be performed as a cycle, as it was at the premier, in the course of several days in August of 1876 in Bayreuth. The premier took place in a specially built theater, the old opera house being too small for Wagner’s orchestra. Wagner’s old patron, King Ludwig II of Bavaria, even though his relationship with Wagner had soured throughout the years, was instrumental in financing the theater. The premier was attended by royalty (Kaiser Wilhelm was there, as well as Ludwig, and Don Pedro, the Emperor of Brazil). The leading musicians of the day were also present: Anton Bruckner, Edvard Grieg, Tchaikovsky, and of course Franz Liszt, Wagner’s father in law. And so was the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, one of the major influences and, for a while, a good friend.

We’ll tackle individual operas of the Ring – Das Rheingold (The Rhinegold), Die Walküre (The Valkyrie), Siegfried and Götterdämmerung – in due course: each one represents a challenging, exasperating, but in the end enormously satisfying, subject. For now, we’ll just play the overture, or the Prelude, as Wagner called it, to Das Rheingold – that’s how the monumental tetralogy starts, the beginning of all beginnings (Sir Georg Solti conducts the Vienna Philharmonic in a 1967 recording).

A very different artist was also born this week, the French composer Jean Françaix. Born 99 years and a day after Wagner, Françaix may be considered Wagner’s opposite. Françaix once said that his goal is to "give pleasure": you would’ve never heard anything similar from Wagner. Françaix was born into a musical family which encouraged his studies. He was still a child when Ravel noticed him and wrote a glowing letter to his father, Alfred, the director of the Le Mans Conservatoire. Françaix studied with Nadia Boulanger who later became his champion, playing and conducting many of his premiers. His work was met enthusiastically. Not very complicated, it had a natural charm and brilliance. In addition to orchestral and ensemble music, Françaix wrote music for ballets (in collaboration with the great choreographer Roland Petit) and a number of film scores. He wrote several operas; La princesse de Clèves (1964) was very well received. Here’s his Concertino for piano and orchestra, from 1932. The pianist is Claude Françaix, Jean’s daughter.Permalink

May 15, 2017. Monteverdi at 450. Claudio Monteverdi, a pioneering figure and one of the most important composers in the history of European music, was baptized on this day in 1567, making it Monteverdi’s 450th anniversary. For the past two years, we’ve celebrated the genius of Monteverdi with detailed entries (here and here). While Monteverdi is rightly famous as one of the very first composers of opera and the most significant one among the early adopters of this new genre, the bulk of his musical output was in madrigals. He published his first book of madrigals in 1587, when he was twenty years old and still living in Cremona, his place of birth. The last four, Books 6 through 9, were published when Monteverdi was in Venice, having left Mantua in 1612. (The last, ninth book, appeared in print posthumously). As an example, here’s a madrigal from his first book, Baci soavi e cari (it’s performed by The Consort of Musicke with the soprano Emma Kirkby, Anthony Rooley conducting). It’s nice but rather conventional. Considering that both Palestrina (d. 1594) and Orlando di Lasso, who died the same year, were still alive and writing great music, and that Gesualdo was at the peak of his creative power, this is not a very memorable achievement. Compare it, for example, with Orlando’s amazing Carmina crhomatico from Prophetiae Sibyllarum, composed years earlier (here; Ensemble De Labyrintho is conducted by Walter Testolin). Monteverdi’s later motets are very different. Consider, for example, the second motet, Hor che 'l ciel e la terra (Now that the sky, earth and wind are silent, after a sonnet by Petrarch) from Book 8 (here, with Concerto Italiano directed by Rinaldo Alessandrini). It’s operatic in style, with dramatic scenes following serene episodes. Monteverdi himself called it Stile concitato (agitated style) and it certainly is.

the genius of Monteverdi with detailed entries (here and here). While Monteverdi is rightly famous as one of the very first composers of opera and the most significant one among the early adopters of this new genre, the bulk of his musical output was in madrigals. He published his first book of madrigals in 1587, when he was twenty years old and still living in Cremona, his place of birth. The last four, Books 6 through 9, were published when Monteverdi was in Venice, having left Mantua in 1612. (The last, ninth book, appeared in print posthumously). As an example, here’s a madrigal from his first book, Baci soavi e cari (it’s performed by The Consort of Musicke with the soprano Emma Kirkby, Anthony Rooley conducting). It’s nice but rather conventional. Considering that both Palestrina (d. 1594) and Orlando di Lasso, who died the same year, were still alive and writing great music, and that Gesualdo was at the peak of his creative power, this is not a very memorable achievement. Compare it, for example, with Orlando’s amazing Carmina crhomatico from Prophetiae Sibyllarum, composed years earlier (here; Ensemble De Labyrintho is conducted by Walter Testolin). Monteverdi’s later motets are very different. Consider, for example, the second motet, Hor che 'l ciel e la terra (Now that the sky, earth and wind are silent, after a sonnet by Petrarch) from Book 8 (here, with Concerto Italiano directed by Rinaldo Alessandrini). It’s operatic in style, with dramatic scenes following serene episodes. Monteverdi himself called it Stile concitato (agitated style) and it certainly is.

Book 8 was published in 1638 but some of the works in it were composed earlier. The set consists of two parts: Madrigals of War (Hor che 'l ciel is one of them) and Madrigals of Love. The war may refer to the terrible events of 1530 during and following the War of Mantuan Succession. Even though Monteverdi was living in Venice, he was considered a citizen of Mantua and was receiving a pension from the Duchy, so these events affected him more than most. Monteverdi left Mantua after the death of the Duke Vincenzo I Gonzaga, in 1612. The sons of Vincenzo, Francesco, who fired Monteverdi, and Ferdinando, died without leaving a male heir. That led to a conflict between the claimants to the duchy, mainly the Holy Roman Empire and France. In July of 1630 the imperial troupes sacked Mantua. That was only part of the tragedy: the invading army also brought the plague. Some of the escaping Mantuans went to Venice and infected that city as well. In the following year, out of Venice’s population of 150,000 almost 50,000 people died. Asking for protection from the Virgin, the city erected the church of Santa Maria della Salute, now part of the Venetian cityscape; music of Monteverdi was played at the foundation ceremony. Whether thru divine intervention or natural causes, by November of 1631 the plague was over. Monteverdi’s mass with the famous Gloria was performed during the celebrations. Rather than playing the excerpts from the Mass, here is one of the Madrigals of Love from Book 8: a lovely Lamento della Ninfa (The Consort of Musicke is conducted by Anthony Rooley).

In April of 1632 Monteverdi entered the priesthood; even so, he continued to write secular music, operas among them. The last one, L’incoronazione di Poppea, was premiered during the Carnival season in 1643. Monteverdi died several months later, on November 29th of that year.Permalink

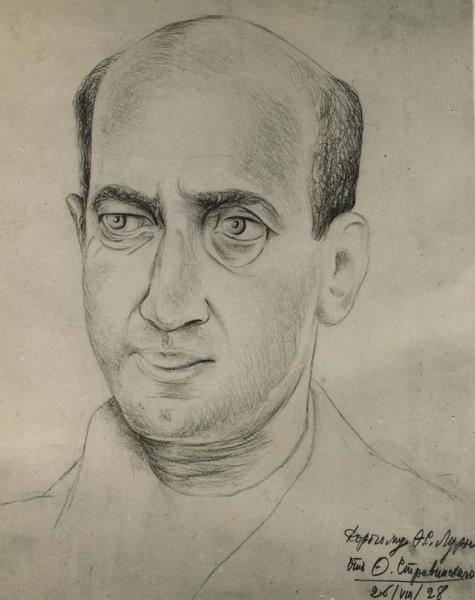

Vera de Bosset brought Lourié and Stravinsky together; she, apparently, was also the reason they fell apart. While in Paris, Lourié continued composing, writing two symphonies and many songs on poetry from Sappho and Dante to Pushkin, Verlaine and Mayakovsky. In 1941 the Germans occupied France and with the help of Serge Koussevitzky Lourié fled to the US. He tried to write music for film, but was not very successfull. His major undertaking was the opera The Blackamoor of Peter the Great, after Pushkin’s novel, which has not been staged to this day. Lourié died in Princeton in 1966.

Vera de Bosset brought Lourié and Stravinsky together; she, apparently, was also the reason they fell apart. While in Paris, Lourié continued composing, writing two symphonies and many songs on poetry from Sappho and Dante to Pushkin, Verlaine and Mayakovsky. In 1941 the Germans occupied France and with the help of Serge Koussevitzky Lourié fled to the US. He tried to write music for film, but was not very successfull. His major undertaking was the opera The Blackamoor of Peter the Great, after Pushkin’s novel, which has not been staged to this day. Lourié died in Princeton in 1966.

May 8, 2017. A fascinating life of a little-known composer. A Russian-French-American composer, an early Futurist, Arthur Lourié was born on May 14th of 1891 in a small town of Propoisk, now in Belarus. Half of the population of the town was Jewish, as was Arthur’s family, though they were reasonably well off as his father was an engineer. In 1899 they moved to Odessa. In 1909 Arthur moved to St-Petersburg and entered the Conservatory where he studied composition with Alexander Glazunov (he never completed his studies and was mostly self-taught). In 1914 Arthur converted to Catholicism and took the name of Arthur-Vincent Lourié, after his favorite painter, Vincent Van Gogh. As part of the artistic elite, he became friends with the poet Anna Akhmatova and was the first to set her verse to music. He also was an acquaintance of the poets Vladimir Mayakovsky and Alexander Blok, and the writer Fyodor Sologub. In 1914, following Marinetti’s example, Lourié, the painter Georgy Yakulov and the poet Benedikt Livshitz published the Russian version of the Futurist Manifesto, “We and the West.” A year later he composed a “futurist” piece called Forms in the Air, which he dedicated to Picasso (you can listen to it here in the performance by the Italian pianist and composer Daniele Lombardi). Extremely innovating, he also wrote several atonal and quarter-tone pieces, in some ways presaging Schoenberg.

Propoisk, now in Belarus. Half of the population of the town was Jewish, as was Arthur’s family, though they were reasonably well off as his father was an engineer. In 1899 they moved to Odessa. In 1909 Arthur moved to St-Petersburg and entered the Conservatory where he studied composition with Alexander Glazunov (he never completed his studies and was mostly self-taught). In 1914 Arthur converted to Catholicism and took the name of Arthur-Vincent Lourié, after his favorite painter, Vincent Van Gogh. As part of the artistic elite, he became friends with the poet Anna Akhmatova and was the first to set her verse to music. He also was an acquaintance of the poets Vladimir Mayakovsky and Alexander Blok, and the writer Fyodor Sologub. In 1914, following Marinetti’s example, Lourié, the painter Georgy Yakulov and the poet Benedikt Livshitz published the Russian version of the Futurist Manifesto, “We and the West.” A year later he composed a “futurist” piece called Forms in the Air, which he dedicated to Picasso (you can listen to it here in the performance by the Italian pianist and composer Daniele Lombardi). Extremely innovating, he also wrote several atonal and quarter-tone pieces, in some ways presaging Schoenberg.

After the October Revolution of 1917, Lourié served in the Department of Education under Anatoly Lunacharsky. For all practical purposes, Lunacharsky, who in the early years after the Revolution supported all kinds of radical artistic innovations, was functioning as Minister of Culture. Lourié was his deputy in charge of music. In Moscow Lourié shared an apartment with Sergei Sudeikin and his wife, Vera de Bosset. Sudeikin was an exceptional painter who became well-known in Paris for his decorations to Diagilev’s ballets. Vera de Bosset, a dancer, would play a very important role in Lourié’s life: in 1920 she and Sudeikin moved to Paris where she met and soon become a lover of (and much later the wife of) Igor Stravinsky. Vera would eventually introduce Lourié to Stravinsky which started a long, if contentious, friendship. Lourié’s work at the Soviet ministry didn’t last long, and in 1921 he moved to Berlin where he befriended Ferruccio Busoni and Edgar Varèse. A year later, in 1922, he moved to Paris, and through Vera met up with Stravinsky. He became one of Stravinsky’s most important supporters, writing articles and speaking on his behalf. There is no doubt that of the two it was Stravinsky who possessed an enormous creative talent but many musicologists point out that Lourié’s compositions may have influenced Stravinsky’s work: for example, Lourié’s A Little Chamber Music (here) was written in 1924, and it sounds stylistically very similar to Stravinsky’s Apollon musagète, which was written three years later, in 1927.

The portrait of Lourié, above, is by Theodore Stravinsky, Igor’s son from his first marriage. The portrait of Vera de Bosset is by Sergei Sudeikin.Permalink

May 1, 2017. Alessandro Scarlatti, Brahms and Tchaikovsky. Scarlatti père was born on May 2nd of 1660 in Palermo, Sicily. These days we know his son, Domenico, the composer of wonderful clavier sonatas, much better, but this has more to do with changes in tastes in musical genres than their relative talents. During his time, Scarlatti, famous for his operas, w as one of the most popular composers in Italy. It’s much more difficult to stage an opera, especially a baroque opera, than perform a piano sonata, thus our familiarity with Alessandro is limited while many of Domenico’s sonatas became popular fare. This is a pity: Alessandro Scarlatti wrote close to 70 operas and some of them are remarkable. One of the finest is Il Mitridate Eupatore, which Scarlatti wrote in 1706; it was premiered in Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo in Venice in January of 1707. Scarlatti moved to Venice from Rome, where performances of operas were forbidden (fortunately, temporarily) by the Pope – Venice, on the other hand, had the most active opera scene in the world. The above mentioned Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo, for example, one of the finest and largest in Venice, was built in 1678. It had five levels of boxes, with 30 boxes in each row, plus stalls for the hoi polloi. In 1709, the theater saw the premier of Handel’s Agrippina. The theater exists to this day, now knowns as Teatro Malibran, after Maria Malibran, the great Spanish mezzo famous for her roles in operas by Rossini and Donizetti (Malibran died in 1836 at the age of 28, the age when most singers would not have yet properly developed their voice). But back to Scarlatti: he soon realized that in Venice, with its dozens of opera theaters, he would have a stiff competition and even the support of Prince Antiono Ottoboni, the father of Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni, wouldn’t guarantee success. Scarlatti’s premonition came true: both of his Venetian operas, Il trionfo della libertà and Il Mitridate Eupator, were met with mixed success at best. Bitterly disappointed, Scarlatti left Venice and, after a stay in Urbino, returned to Rome. Much of the score of Il trionfo is lost but fortunately for us, Mitridate survived and is staged, if not often, to this day. Its music is marvelous, as you can judge for yourself. Here is Cara tomba, sung by the soprano Simone Kermes; here – a Dolce stimola with the incomparable Joan Sutherland.

as one of the most popular composers in Italy. It’s much more difficult to stage an opera, especially a baroque opera, than perform a piano sonata, thus our familiarity with Alessandro is limited while many of Domenico’s sonatas became popular fare. This is a pity: Alessandro Scarlatti wrote close to 70 operas and some of them are remarkable. One of the finest is Il Mitridate Eupatore, which Scarlatti wrote in 1706; it was premiered in Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo in Venice in January of 1707. Scarlatti moved to Venice from Rome, where performances of operas were forbidden (fortunately, temporarily) by the Pope – Venice, on the other hand, had the most active opera scene in the world. The above mentioned Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo, for example, one of the finest and largest in Venice, was built in 1678. It had five levels of boxes, with 30 boxes in each row, plus stalls for the hoi polloi. In 1709, the theater saw the premier of Handel’s Agrippina. The theater exists to this day, now knowns as Teatro Malibran, after Maria Malibran, the great Spanish mezzo famous for her roles in operas by Rossini and Donizetti (Malibran died in 1836 at the age of 28, the age when most singers would not have yet properly developed their voice). But back to Scarlatti: he soon realized that in Venice, with its dozens of opera theaters, he would have a stiff competition and even the support of Prince Antiono Ottoboni, the father of Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni, wouldn’t guarantee success. Scarlatti’s premonition came true: both of his Venetian operas, Il trionfo della libertà and Il Mitridate Eupator, were met with mixed success at best. Bitterly disappointed, Scarlatti left Venice and, after a stay in Urbino, returned to Rome. Much of the score of Il trionfo is lost but fortunately for us, Mitridate survived and is staged, if not often, to this day. Its music is marvelous, as you can judge for yourself. Here is Cara tomba, sung by the soprano Simone Kermes; here – a Dolce stimola with the incomparable Joan Sutherland.

Johannes Brahms was born on May 7th of 1833, and exactly seven years later so was Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Every year we try to compare the two: both wrote wonderful symphonies, their violin concertos are among the best ever written, and the same could be said about Tchaikovsky’s First piano concerto and Brahms’s First and, maybe even more so, his Second. Still, the basic truth is that while they worked during the same period, it’s hard to imagine two composers more different than the conservative follower of Beethoven and the Russian nationalist Romantic. One thing they do have in common is their songs: both wrote absolutely wonderful songs which were overshadowed by their larger compositions. Brahms wrote songs throughout his whole life, from his Six songs op. 3 to the Five songs, op 107. Altogether he wrote about 200 songs. Here’s his Sapphische Ode, op.94, no. 4, sung by the soprano Bernarda Fink with Anthony Spiri on the piano. The same performer can be heard here in Brahms’s song Feldeinsamkeit, op.86, no. 2. Tchaikovsky’s song output is smaller but contains many gems. Here are two songs from his Op. 54, Song for Children. First, Lullaby in a Storm, from op. 54 and then, Child’s song (“My Lizochek”). The soprano Ljuba Kazarnovskaya is accompanied by Ljuba Orfenova.Permalink

April 24, 2017. Prokofiev. Confusion surrounds the birth date of Sergei Prokofiev. One problem is calendar-related: when he was born, Russia was using the old Julian calendar. Prokofiev.jpg) himself always thought that he was born on April 11th of 1891. When Russia moved to the Gregorian calendar after the October Revolution, April 11th became April 23rd while, quite confusingly, the anniversary of the revolution itself fell on November 7th. Prokofiev celebrated his birthday on the 23rd, but that’s not what is written in the existing copy of his birth certificate, which says that he was born on April 15th (old style), or April 27th. Last year we celebrated Prokofiev’s 125th anniversary and we wrote about him in some detail. Prokofiev’s life, like the lives of so many Russian artists of that time, can be divided in geographic periods: Russia, America, Europe, the USSR. He was born in the village of Sontsovka, not far from the present-day Donetsk, where his father managed an estate. His mother gave him his first piano lessons. At the age of 11, while in Moscow, he was introduced to Sergei Taneyev , who was quite impressed and asked his friend, composer Reinhold Glière, to give Prokofiev lessons in composition. A year later Prokofiev entered the St-Petersburg conservatory, where his studied with Lyadov and Rimsky-Korsakov. A brilliant pianist and promising composer, he became famous early, even though the more conservative public was scandalized by works like The Scythian Suite. After the Revolution Prokofiev emigrated to the United States, thus starting the second and rather short period of his life. His time in the US was not very happy: as a pianist, he had to compete with the very successful Rachmaninov, and as a composer – with the more famous Stravinsky. He did compose a very successful opera The Love for Three Oranges, but as his career was not progressing, he moved to Europe, thus entering the third phase of his life. Prokofiev lived in Europe from 1922 to 1936, first in Germany and then in Paris. He married a Spanish singer, Lina Lubera, continued composing for Diagilev and mended his ways with Stravinsky, who considered Prokofiev the greatest Russian composer – after himself. Unlike Stravinsky, Prokofiev continued to maintain relationships with Soviet musicians and even wrote music for a Soviet film, Lieutenant Kijé (he reused the music in a very popular suite). He even received a commission from the Mariinsky theater, then recently renamed the Kirov, to create a ballet, Romeo and Juliet. As his links with the Soviet musical establishment grew, he was offered to return to Russia; he accepted in 1936. Why he made this fateful decision, considering the purges and recent condemnation of Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk, we’ll never know.

himself always thought that he was born on April 11th of 1891. When Russia moved to the Gregorian calendar after the October Revolution, April 11th became April 23rd while, quite confusingly, the anniversary of the revolution itself fell on November 7th. Prokofiev celebrated his birthday on the 23rd, but that’s not what is written in the existing copy of his birth certificate, which says that he was born on April 15th (old style), or April 27th. Last year we celebrated Prokofiev’s 125th anniversary and we wrote about him in some detail. Prokofiev’s life, like the lives of so many Russian artists of that time, can be divided in geographic periods: Russia, America, Europe, the USSR. He was born in the village of Sontsovka, not far from the present-day Donetsk, where his father managed an estate. His mother gave him his first piano lessons. At the age of 11, while in Moscow, he was introduced to Sergei Taneyev , who was quite impressed and asked his friend, composer Reinhold Glière, to give Prokofiev lessons in composition. A year later Prokofiev entered the St-Petersburg conservatory, where his studied with Lyadov and Rimsky-Korsakov. A brilliant pianist and promising composer, he became famous early, even though the more conservative public was scandalized by works like The Scythian Suite. After the Revolution Prokofiev emigrated to the United States, thus starting the second and rather short period of his life. His time in the US was not very happy: as a pianist, he had to compete with the very successful Rachmaninov, and as a composer – with the more famous Stravinsky. He did compose a very successful opera The Love for Three Oranges, but as his career was not progressing, he moved to Europe, thus entering the third phase of his life. Prokofiev lived in Europe from 1922 to 1936, first in Germany and then in Paris. He married a Spanish singer, Lina Lubera, continued composing for Diagilev and mended his ways with Stravinsky, who considered Prokofiev the greatest Russian composer – after himself. Unlike Stravinsky, Prokofiev continued to maintain relationships with Soviet musicians and even wrote music for a Soviet film, Lieutenant Kijé (he reused the music in a very popular suite). He even received a commission from the Mariinsky theater, then recently renamed the Kirov, to create a ballet, Romeo and Juliet. As his links with the Soviet musical establishment grew, he was offered to return to Russia; he accepted in 1936. Why he made this fateful decision, considering the purges and recent condemnation of Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk, we’ll never know.

The Soviets promised him a good life and artistic freedom, and initially that’s how it worked. Prokofiev adapted his work according to the political climate, writing songs on patriotic texts and a cantata in 10 movements for the 20th Anniversary of the October Revolution, whose orchestration included a military band and several accordions. (Despite all this the Cantata had to wait its premier till 1966). Then, in 1941 Germany attacked the Soviet Union, and Prokofiev, like all important artists, was evacuated to the eastern parts of the country. Despite the hardship he continued to compose, which to some extent was easier as the musical censorship was relaxed. The three War piano sonatas and most of the opera War and Peace come from that period. And then, as the war ended, “Zhdanovshchina” erupted. While Stalin’s underlings Yezhov and Beria were terrorizing people physically, Andrei Zhdanov, Stalin’s chief ideolog, terrorized the Soviet cultural elite. He started with the writers and the poets in 1946, then moved on to condemnations of theater and film. Then, in 1948 the Politburo of the Communist Party issued a resolution criticizing “formalism” in classical music. We’ll consider the tragic consequences of this resolution another time. Here, from a much happier period, is Prokofiev’s answer to Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring – his Scythian Suite. Claudio Abbado conducts the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.Permalink

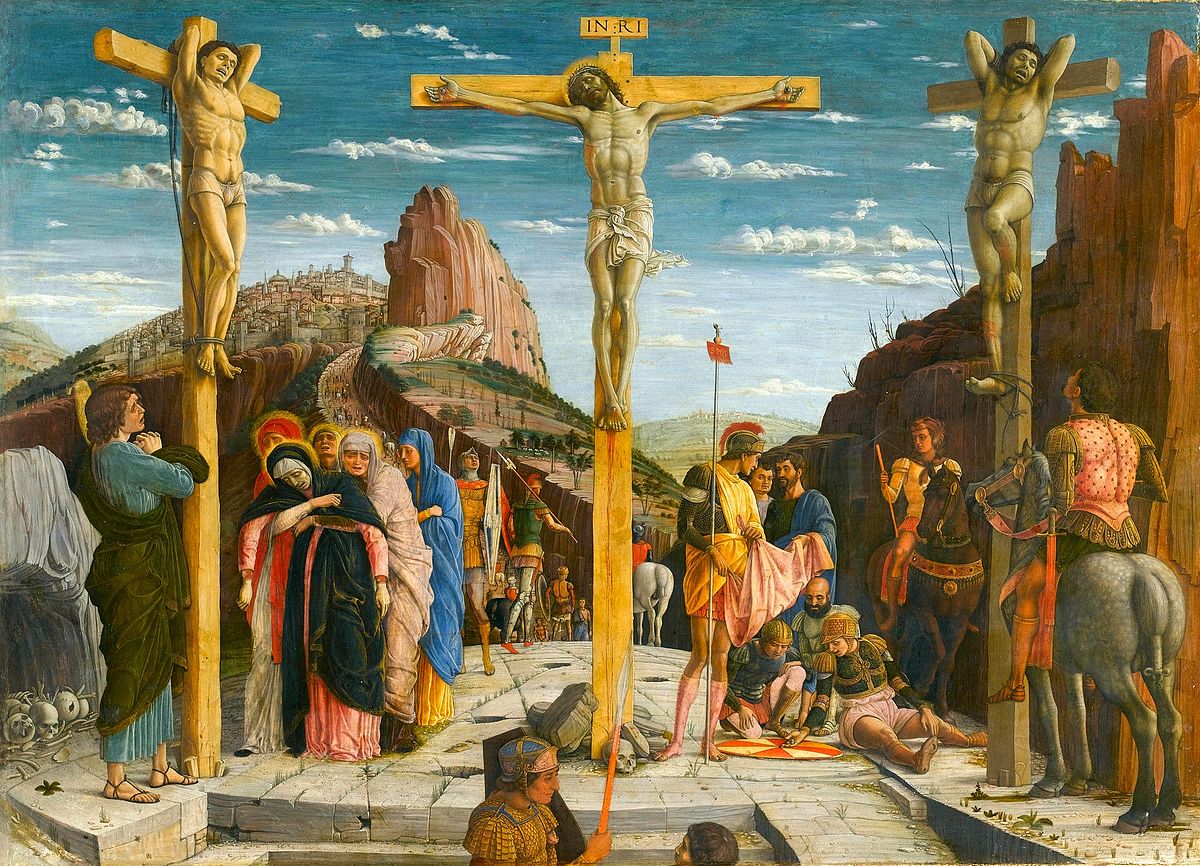

April 17, 2017. Happy Easter! The Eastern Orthodox churches use the Julian calendar; the Western Churches – the Gregorian that we all are accustomed to. Both use arcane methods (phases of the moon come into play) to derive the dates of Easter Sundays. Once in a while these obscure calculations end up with the same date, as it happened this year (we won’t have another one till 2025). In addition, Passover this year started on Monday, April 10th and runs through April 18th, making for an unusually rich holiday period.

till 2025). In addition, Passover this year started on Monday, April 10th and runs through April 18th, making for an unusually rich holiday period.

The Western tradition of writing music for Easter goes back to the Middle Ages and became especially strong during the Renaissance. In 1585, the great Spanish composer Tomás Luis de Victoria published a set of 18 motets called Tenebrae responsories sung during the Latin services on Thursday, Friday and Saturday of the Holy week. Here’s one of these motets, O vos omnes (All you who walk by on the road), sung on Saturday. It’s performed by the ensemble Tallis Scholars. About 25 years later, Carlo Gesualdo wrote his own setting of Tenebrae responsories. It’s an amazing vocal piece whose tonal modulations sound startling even today. Here’s Omnes amici mei dereliquerunt me (All my friends have deserted me) for Good Friday. The Taverner Consort is conducted by Andrew Parrott. Both settings above were created for a Catholic service. When Thomas Tallis composed his Lamentations of Jeremiah sometime in the 1570s, England’s Anglican Church had already separated from Rome, although it’s not clear whether Lamentations were composed for the Catholic or Anglican service. In England of the late 16th century the settings of the Lamentations were traditionally performed at the Tenebrae service of the Holy week. Many settings were written – William Byrd for example, created one. Tallis’s is probably the most profound. Here’s the first part, performed by the ensemble Magnificat, Philip Cave conducting.

Johann Sebastian Bach composed some of the greatest music for Easter: two sets of Passions, one, set to the chapters of the Gospel according to St. John, another – St. Matthew. Bach’s obituary mentions five Passions but these two the only ones extant. Bach also wrote Easter Oratorio, the first version of which was completed the same year as the St. Matthew Passion, 1725. Here’s the first part of St. John Passion. Concentus Musicus Wien and Arnold Schoenberg Choir are conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt.

The Eastern orthodox church historically lacked the tradition of “composed” music. Different chants, the so-called Znamenny chant being the major one, were used for centuries. These chants go back to the Byzantine service and are written not in notes but special signs . Only at the end of the 19th century did Russian composers turn to the liturgical music, Alexander Gretchaninov and especially Sergei Rachmaninov among them. There are many recordings of the traditional services, but the one created by the choir of the Chevetogne Abbey is especially interesting. They Abbey is dedicated to Christian unity and though it is a Benedictine abbey, it has both Western rite and Eastern rite churches and made recordings of both Eastern and Latin services. Here’s the first part of the Service for Holy Saturday, performed by the Choir of the Abbey of Chevetogne.Permalink