Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

December 5, 2016. Berlioz, Les Troyens. Several wonderful composers were born this week: Francesco Geminiani, on this day in 1687 in Lucca, a somewhat minor but still interesting Baroque composer and violinist; Henryk Górecki, on December 6th of 1933 – a leading Polish modernist (and, surprisingly, commercially successful) composer; Bernardo Pasquini, December 7th of 1637 in Tuscany, an important opera and keyboard composer of the Alessandro Scarlatti and Antonio Corelli generation. And then, also on December 7th but of 1863, another Italian – Pietro Mascagni of the Cavalleria Rusticana fame. The following day, December 8th, is the birthday of the Finnish national composer, Jean Sibelius; he was born in 1865. Also on the same day but in 1890, a leading Czech composer of the early 20th century was born – Bohuslav Martinu, who used a neoclassical idiom and, sometimes, jazz, as in his whimsical La Revue de Cuisine. Also on the same day was born a wonderful Soviet composer Mieczysław (Moisey) Weinberg. Weinberg was born in Warsaw, fled to the Soviet Union at the outbreak of WWII (his family stayed behind and perished during the Holocaust), and eventually became “the third great Soviet composer,” after Shostakovich and Prokofiev, except that he remained practically unknown to the public: his work was banned during the Stalin time, in 1953 he was arrested during the anti-Jewish campaign and survived only because Stalin died several months later. Even though Weinberg was “rehabilitated” by the Soviets, performances of his music were rare. During the last 10 years, his opera The Passenger gained prominence after being staged in several major theaters, including the Lyric Opera. Also this week (and what a week!), two more birthdays on the 10th of December: César Franck, born in 1822, and one of the greatest composers of the 20th century, Olivier Messiaen, in 1908.

modernist (and, surprisingly, commercially successful) composer; Bernardo Pasquini, December 7th of 1637 in Tuscany, an important opera and keyboard composer of the Alessandro Scarlatti and Antonio Corelli generation. And then, also on December 7th but of 1863, another Italian – Pietro Mascagni of the Cavalleria Rusticana fame. The following day, December 8th, is the birthday of the Finnish national composer, Jean Sibelius; he was born in 1865. Also on the same day but in 1890, a leading Czech composer of the early 20th century was born – Bohuslav Martinu, who used a neoclassical idiom and, sometimes, jazz, as in his whimsical La Revue de Cuisine. Also on the same day was born a wonderful Soviet composer Mieczysław (Moisey) Weinberg. Weinberg was born in Warsaw, fled to the Soviet Union at the outbreak of WWII (his family stayed behind and perished during the Holocaust), and eventually became “the third great Soviet composer,” after Shostakovich and Prokofiev, except that he remained practically unknown to the public: his work was banned during the Stalin time, in 1953 he was arrested during the anti-Jewish campaign and survived only because Stalin died several months later. Even though Weinberg was “rehabilitated” by the Soviets, performances of his music were rare. During the last 10 years, his opera The Passenger gained prominence after being staged in several major theaters, including the Lyric Opera. Also this week (and what a week!), two more birthdays on the 10th of December: César Franck, born in 1822, and one of the greatest composers of the 20th century, Olivier Messiaen, in 1908.

But the composer we really wanted to talk about, notwithstanding the immense talent we just listed above, is Hector Berlioz, born on December 11th of 1803. And the reason is not that he’s one of the greatest composers of all time (which of course he is) but that the Lyric Opera of Chicago is currently staging his monumental opera, Les Troyens. It is long, about 3 hours and 40 minutes of music (plus intermissions that push the performance closer to 5 hours altogether), it is intense – no recitatives, no frilly entr'actes, just continuous orchestral and vocal music. And despite it consisting of two separate parts and five acts, the libretto is surprisingly coherent, unlike some of Wagner’s undertakings. Berlioz wrote the libretto himself, after Virgil’s poem Aeneid. The first part, called The Taking of Troy, which starts in Troy after the apparent departure of the Greeks, describes Cassandra’s futile attempts to warn the Trojans of the looming dangers. The Trojans, relieved that the war is over, do not believe her till it’s too late: the infamous giant horse, which the Greeks left as a “gift,” is full of soldiers. They pillage and murder; Trojan women commit suicide rather than falling into slavery, while the ghost of Hector convinces Aeneas, who’s ready to fight to the end, to leave the fallen city and build a new Troy, which of course is Rome. The second part takes place in Carthage, ruled by Queen Dido. Aeneas and his cohorts, after being lost at sea, find refuge there. The chaste queen, who still mourns her husband, eventually falls in love with Aeneas, and though they lead an idyllic life, it’s clear that Aeneas must leave, as he has a mission – to build the new Troy. The ghost of Hector, this time accompanied by the dead Cassandra and King Priam, remind him of that mission, and, reluctantly, Aeneas gathers his men and sets sail for Italy. Dido is furious that Aeneas abandoned her. She burns all the gifts she received from Aeneas, prophesizes that a general from Carthage will take revenge on Rome (as Hannibal did, to an extent), and then stabs herself to death.

In the Chicago production Susanne Graham was superb as Dido. Here she is in the Morte de Didonne scene. This 2003 Paris recording features Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, John Eliot Gardiner conducting. And here is the famous Chasse royale et orage (The Royal hunt and the storm) purely orchestral ballet scene, performed by the Royal Opera House orchestra, Sir Colin Davis conducting.

PermalinkNovember 28, 2016. Lully, Part I. Jean-Baptiste Lully was born on this day in 1632 in Florence, Tuscany. His family was of modest means and not musical. Giovanni Battista, as he was called in those days, probably studied music with local friars. Then his life changed overnight. How it happened that Roger de Lorraine, the chevalier de Guise, picked a 14-year old boy to become a tutor in Italian for his niece, we don’t know. What we do know is that the niece was none other than Anne-Marie-Louise d’Orléans, known as the “Grande Mademoiselle,” the eldest daughter of Gaston, the Duke of Orléans, a brother of Louis XIII and, therefore, the niece of King Louis XIV. The Grande Mademoiselle, then 19, was living in the Palais des Tuileries, and it was in the palace that Jean-Baptiste completed his musical education. One wonders whether Lully had any knowledge of Italian music before he was brought to France; it seems likely that he became familiar with it later on, when he was already employed by the court. In addition to music, Jean-Baptiste was taught to dance, and, apparently was very good at that – at least that was the capacity in which he started at the Royal court. The Second Fronde (the Fronde of the Nobles) compromised the position of the Grande Mademoiselle, and in 1653 she was forced to leave Paris. Soon after, Jean-Baptiste returned to the city and was brought to the court as a dancer in a Ballet royal de la nuit, a sumptuous production which called for a large number of performers. (The 14-year old King, who loved to dance, performed as Apollo – it was his debut). The performance went well and Lully was accepted to the corp. As Lully was already dabbling in composition, he was appointed a “composer of instrumental music,” but his duties were to combine dancing and composing, with an emphasis on dancing. Jean-Baptiste was so good at it that he got noticed by the King. Soon he became the King’s favorite – first as a dancer and, later, as a composer. Back then, the traditions of French court music were rather unusual, at least by our standards. For example, several composers were supposed to create a single ballet. The ballets were complex affairs, not just with dances but also with different vocal parts and instrumental interludes. Some composers were considered to be especially good in writing vocal music, while others were famous as instrumentalists (the young Lully was known for his dance music). For example, Ballet de la Nuit, mentioned above, was written by at least three people. It wasn’t till 1656 that Lully would have a chance to create a complete ballet of his own, L'Amour malade; that happened partly because of the influence of the Italian musicians in the entourage of the King’s chief advisor, Cardinal Mazarin, himself an Italian. L'Amour malade, a vast production with mimes, dancers (Lully being one of them) and singers, was a huge success. From that point on, he was considered the greatest ballet composer in France. That would become his main preoccupation for the next several years: he would write ballets for the court and even add ballet scenes to operas of other composers. A rather scandalous story happened when the famous Italian opera composer, Francesco Cavalli, came to town with his fine opera, Ercole amante. Lully decided to add several ballet pieces to it. The entire production became a six-hour affair; the king, the queen and the court danced to the ballet music, which received all the praise, while the rest of the opera was panned. Cavalli left Paris soon after.

music with local friars. Then his life changed overnight. How it happened that Roger de Lorraine, the chevalier de Guise, picked a 14-year old boy to become a tutor in Italian for his niece, we don’t know. What we do know is that the niece was none other than Anne-Marie-Louise d’Orléans, known as the “Grande Mademoiselle,” the eldest daughter of Gaston, the Duke of Orléans, a brother of Louis XIII and, therefore, the niece of King Louis XIV. The Grande Mademoiselle, then 19, was living in the Palais des Tuileries, and it was in the palace that Jean-Baptiste completed his musical education. One wonders whether Lully had any knowledge of Italian music before he was brought to France; it seems likely that he became familiar with it later on, when he was already employed by the court. In addition to music, Jean-Baptiste was taught to dance, and, apparently was very good at that – at least that was the capacity in which he started at the Royal court. The Second Fronde (the Fronde of the Nobles) compromised the position of the Grande Mademoiselle, and in 1653 she was forced to leave Paris. Soon after, Jean-Baptiste returned to the city and was brought to the court as a dancer in a Ballet royal de la nuit, a sumptuous production which called for a large number of performers. (The 14-year old King, who loved to dance, performed as Apollo – it was his debut). The performance went well and Lully was accepted to the corp. As Lully was already dabbling in composition, he was appointed a “composer of instrumental music,” but his duties were to combine dancing and composing, with an emphasis on dancing. Jean-Baptiste was so good at it that he got noticed by the King. Soon he became the King’s favorite – first as a dancer and, later, as a composer. Back then, the traditions of French court music were rather unusual, at least by our standards. For example, several composers were supposed to create a single ballet. The ballets were complex affairs, not just with dances but also with different vocal parts and instrumental interludes. Some composers were considered to be especially good in writing vocal music, while others were famous as instrumentalists (the young Lully was known for his dance music). For example, Ballet de la Nuit, mentioned above, was written by at least three people. It wasn’t till 1656 that Lully would have a chance to create a complete ballet of his own, L'Amour malade; that happened partly because of the influence of the Italian musicians in the entourage of the King’s chief advisor, Cardinal Mazarin, himself an Italian. L'Amour malade, a vast production with mimes, dancers (Lully being one of them) and singers, was a huge success. From that point on, he was considered the greatest ballet composer in France. That would become his main preoccupation for the next several years: he would write ballets for the court and even add ballet scenes to operas of other composers. A rather scandalous story happened when the famous Italian opera composer, Francesco Cavalli, came to town with his fine opera, Ercole amante. Lully decided to add several ballet pieces to it. The entire production became a six-hour affair; the king, the queen and the court danced to the ballet music, which received all the praise, while the rest of the opera was panned. Cavalli left Paris soon after.

Here are several excerpts from an early ballet by Lully called Ballet des Plaisirs. It was composed in 1655; Lully danced several roles in the production. Aradia Baroque Ensemble, a Canadian group, is conducted by Kevin Mallon.Permalink

November 21, 2016. Eight composers in seven days. This is one of the weeks when practically every day allows us to celebrate a talented, if not necessarily great, composer. Monday is Francisco Tarrega’s birthday: he was born on November 21st of 1852 in Villareal, Spain. A virtuoso guitarist and an imaginative, if rather conservative, composer, he was part of the romantic revival of Spanish music at the second half of the 19th century. A friend of Isaac Albéniz and Enrique Granados, he lived most of his life in Barcelona. Here’s one of his most famous compositions, Capricho Árabe, performed by Eric Henderson. And speaking of guitar compositions, some of the most famous were written by another Spanish composer whose birthday falls on Tuesday: Joaquin Rodrigo, the author of Concierto de Aranjuez and Concierto Andaluz was born on November 22nd of 1901. Rodrigo went blind at the age of three after contracting diphtheria. This didn’t stop him from composing (he wrote in Braille music code which was then transcribed into regular music notation), studying and travelling. He went to Paris to study with Paul Dukas and it was in Paris that he composed his most famous piece, Concierto de Aranjuez for the guitar and orchestra. It’s interesting that while Tarrega was a virtuoso guitar player, Rodrigo never learned to play the instrument. Here’s another well-known piece by Rodrigo written for the guitar and orchestra: his Fantasía para un gentilhombre (Fantasia for a Gentleman). Fantasia was written at the request of Andrés Segovia who premiered it in 1958. Segovia is the soloist in this recording, and the conductor, Enrique Jordá, was conducting the premier. The orchestra, though, is different: in the recording it’s “Symphony Of The Air”, while the premier was played by the San Francisco Symphony.

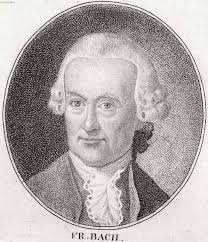

Also on Tuesday we mark the birthday of Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, Johan Sebastian’s oldest son. Friedmann was born on November 22nd of 1710 in Weimar, where his father worked in the employ of Wilhelm Ernst, duke of Saxe-Weimar. A talented composer, he never found satisfying employment throughout his entire life. As a young man, he worked as the organist at Sophienkirche in Dresden, then moved to Halle, taking the appointment at Liebfrauenkirch. While his early years in Halle seemed to be agreeable, eventually Friedemann grew unsatisfied with his position, and so were his superiors. He left Halle without securing employment anywhere else and spent the rest of his life in difficult circumstances. Eventually he was forced to sell his music library, which also contained the sheet music he inherited from his father. Friedemann died on July 1st of 1784 in Berlin, still remembered as a supreme organist and a major composer but leaving his family in poverty. Here’s a lovely Duet for two violas, performed by Ryo Terakado and François Fernandez of the Ricercar Consort.

Friedmann was born on November 22nd of 1710 in Weimar, where his father worked in the employ of Wilhelm Ernst, duke of Saxe-Weimar. A talented composer, he never found satisfying employment throughout his entire life. As a young man, he worked as the organist at Sophienkirche in Dresden, then moved to Halle, taking the appointment at Liebfrauenkirch. While his early years in Halle seemed to be agreeable, eventually Friedemann grew unsatisfied with his position, and so were his superiors. He left Halle without securing employment anywhere else and spent the rest of his life in difficult circumstances. Eventually he was forced to sell his music library, which also contained the sheet music he inherited from his father. Friedemann died on July 1st of 1784 in Berlin, still remembered as a supreme organist and a major composer but leaving his family in poverty. Here’s a lovely Duet for two violas, performed by Ryo Terakado and François Fernandez of the Ricercar Consort.

Also born on the same day, November 22nd, was one of the most important composers of the 20th century, Benjamin Britten. And speaking of important 20th century composers: three more were born this week. Krzysztof Penderecki on November 23rd of 1933, Alfred Schnittke on November 24th of 1934, and Virgil Thomson on November 25th of 1897. And to round things out, we should mention Sergei Taneyev, a prolific composer, a wonderful pianist and a good friend of Tchaikovsky’s (he successfully premiered Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto in Moscow after it flopped in St-Petersburg where Gustav Kross was the soloist). Taneyev was born on November 25th of 1856.Permalink

November 14, 2016. Paul Hindemith. One of the most important composers of the 20th century, Paul Hindemith was born on November 16th of 1895 in Hanau, near Frankfurt. Paul’s father, a painter, was a music lover and insisted that his children study music: Paul played violin, his sister studied the piano and their younger brother – the cello. Some year later they would play in public as the “Frankfurt Children’s Trio,” with their father sometimes accompanying them on the zither. Paul attended the Frankfurt Conservatory, concentrating in violin and later, in 1912, adding classes in composition (his first composition teacher was Arnold Mendelssohn, a great-nephew of Felix Mendelssohn). While at the conservatory, Hindemith wrote his first compositions, which were technically strong, very romantic (just the opposite of what would become his later style) but not terribly inventive. In 1914 he joined the orchestra of the Frankfurt Opera and soon became the concertmaster. Three years into the war he was conscripted; he served mostly in a military band but at the end of the war spent some time in the trenches. He remembered how in March of 1918 he and his fellow musicians were playing Debussy’s String Quartet when it was announced on the radio (sic!) that Debussy had died. When after the war he returned to Frankfurt, he switched from the violin to the viola; he continued playing in the opera orchestra and with the Rebner Quartet.

a music lover and insisted that his children study music: Paul played violin, his sister studied the piano and their younger brother – the cello. Some year later they would play in public as the “Frankfurt Children’s Trio,” with their father sometimes accompanying them on the zither. Paul attended the Frankfurt Conservatory, concentrating in violin and later, in 1912, adding classes in composition (his first composition teacher was Arnold Mendelssohn, a great-nephew of Felix Mendelssohn). While at the conservatory, Hindemith wrote his first compositions, which were technically strong, very romantic (just the opposite of what would become his later style) but not terribly inventive. In 1914 he joined the orchestra of the Frankfurt Opera and soon became the concertmaster. Three years into the war he was conscripted; he served mostly in a military band but at the end of the war spent some time in the trenches. He remembered how in March of 1918 he and his fellow musicians were playing Debussy’s String Quartet when it was announced on the radio (sic!) that Debussy had died. When after the war he returned to Frankfurt, he switched from the violin to the viola; he continued playing in the opera orchestra and with the Rebner Quartet.

The period starting around 1920 was very productive one; that was also the time when Hindemith found his voice, dropping romanticism in favor of expressionism. An interesting example is his sexually charged one-act opera, Sancta Susanna (the protagonist, a nun, gives in to her erotic fantasies; Satan seems to be very active). The performance created a scandal; it is said that in Hamburg, attendees were required to pledge, in writing, to not cause a disturbance. Here it is, in its entirety – Susanna is just 25 minutes long. The American soprano Helen Donath, who had worked mostly in Germany, is Susanna; The Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra is conducted by Gerd Albrecht.

We are used to thinking of Hindemith as a cerebral composer of complex, contrapuntal music. Many compositions from the early 1920s are very different: very expressive, even wild. Grove Music Dictionary gives us a wonderful quote from Hindemith. Regarding the performance of the last movement of his piano Suite 1922, he says: “Disregard what you learnt in your piano lessons. Don’t spend too much time considering whether to strike D# with the fourth or the sixth finger. Play this piece in a very wild manner, but always keep it very strict rhythmically, like a machine. Look on the piano here as an interesting kind of percussion instrument and treat accordingly.” Here’s Suite 1922 in the excellent performance by a Swiss pianist Esther Walker. Ms. Walker is a big proponent of Hindemith’s music and is currently in a process of recording complete piano works of the composer.

Starting around 1923, Hindemith’s style underwent a significant change as he entered his Neo-classical phase, sometimes called the New Objectivity. He also married Gertrud Rottenburg, the daughter of the Jewish conductor of the Frankfurt opera, Ludwig Rottenberg. How this affected Hindemith’s artistic and person life we’ll consider another time.Permalink

November 7, 2016. Couperin le Grand. François Couperin, one of the most important French composers of the end of the 17th – early 18th century, was born on November 10th of 1668. He’s one of the three great composers who defined the French Baroque, born 32 years after Jean-Baptiste Lully and 15 years ahead of Jean-Philippe Rameau. Couperin came from a famous musical family: his uncle, Louis Couperin, was a noted composer and the organist at the church of St-Gervais in central Paris. After Louis’s death, François’s father Charles assumed the post. François’s father died in in 1679; the young François was so promising and obviously talented that the church agreed to hire him as the organist on his 18th birthday. In the interim, François played there often and was practically a full-time organist at St-Gervais even before his official appointment. At the age of 20 François married a girl from a wealthy bourgeois family; her connections helped him to acquire the royal privilege to print and sell his music. A year later Couperin published a collection of organ works, but it was his fame as an organist that brought him to the attention of the court. In 1693, at the age of 25, he received a fabulous appointment as the organist to the court of Louis XIV. Around that time, he wrote a set of trio sonatas, which were later incorporated into a larger selection published under the title of Les nations. The sonatas were clearly modelled after asimilar set of trio sonatas by Arcangelo Corelli, who was Couperin’s favorite composer. As Couperin himself related later on in a preface to the publication, he indulged in a bit of subterfuge in order to promote his work. Knowing that the French were still enamored with all things Italian while looking down at local composers, he concocted a story about an Italian origin of the first sonata. He even made up an Italianate name of the “composer” by rearranging letters of his own name. The sonata was received very favorably, which encouraged Couperin to continue composing.

great composers who defined the French Baroque, born 32 years after Jean-Baptiste Lully and 15 years ahead of Jean-Philippe Rameau. Couperin came from a famous musical family: his uncle, Louis Couperin, was a noted composer and the organist at the church of St-Gervais in central Paris. After Louis’s death, François’s father Charles assumed the post. François’s father died in in 1679; the young François was so promising and obviously talented that the church agreed to hire him as the organist on his 18th birthday. In the interim, François played there often and was practically a full-time organist at St-Gervais even before his official appointment. At the age of 20 François married a girl from a wealthy bourgeois family; her connections helped him to acquire the royal privilege to print and sell his music. A year later Couperin published a collection of organ works, but it was his fame as an organist that brought him to the attention of the court. In 1693, at the age of 25, he received a fabulous appointment as the organist to the court of Louis XIV. Around that time, he wrote a set of trio sonatas, which were later incorporated into a larger selection published under the title of Les nations. The sonatas were clearly modelled after asimilar set of trio sonatas by Arcangelo Corelli, who was Couperin’s favorite composer. As Couperin himself related later on in a preface to the publication, he indulged in a bit of subterfuge in order to promote his work. Knowing that the French were still enamored with all things Italian while looking down at local composers, he concocted a story about an Italian origin of the first sonata. He even made up an Italianate name of the “composer” by rearranging letters of his own name. The sonata was received very favorably, which encouraged Couperin to continue composing.

In addition to the position of the Royal organist, Couperin was appointed the harpsichordist to the court. He also continued to work at the church of St-Gervais. He had many students, most from noble families. And still he found time to compose. In 1713 he published the first book of harpsichord pieces; eventually he would publish three more. In 1715 Louis XIV died and was succeed by the regency, as Louis XV, the future king, was too young to rule. Couperin retained his position at the court and continued with all his commitments and composing. By his contemporaries he was considered probably the greatest composer of his generation, and clearly the best composer for the harpsichord. Couperin became less productive in the last years of his life as his health was failing him. He died on September 11th of 1733. Couperin wrote in many genres: instrumental chamber music, music for the organ, some vocal music, but he excelled above all at composing for the harpsichord.

<Couperin inspired many composers, none more than Richard Strauss, who wrote not one but two symphonic pieces after Couperin’s harpsichord pieces. Let’s listen to several of the originals and then the Divertimento by Richard Strauss. First, the three pieces by Couperin: La Visionnaire, performed by Blandine Rannou, Musétes de Choisi et de Taverni, performed by Lionel Party, and Le tic-toc-choc, ou Les maillotins, played by Jory Vinocur. And here’s how Strauss adapted them for the orchestra. The Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra is conducted by Hirogi Wakasugi.Permalink

October 31, 2016. Bellini and Sweelinck. Vincenzo Bellini was born on October 3rd of 1801 in Catania, Sicily. We don’t write about opera composers very often, opera being a stepchild at Classical Connect; the reasons are purely technical, we do love a good opera. Even though Bellini lived for just 33 years he managed to create several masterpieces that belong to the pantheon of operatic art and have been continuously performed throughout the past 200 years. It’s interesting to note that at the beginning of the 19th century, before Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti produced their major works, Italian opera and composing in general, were not doing well. Opera was born in Italy, and for a century (the 17th, to be exact) Italians were by far the major innovators, even if we consider the talents of Lully, an Italian working in France, and Rameau, the first truly French opera composer. Things changed with George Frideric Handel, a German who absorbed the Italian tradition of Opera Seria and became (in England, of all the places) the major opera composer of his generation. Things shifted to Germany completely by the mid-18th century, with Gluck and especially, Mozart, producing masterpieces above anything else written in the genre. So, when in 1813, Rossini came up with his first major success, L'italiana in Algeri, and then, three years later, created Il barbiere di Siviglia, that ended a drought that lasted for almost 100 years. And in the following 20 years, between the three of them, Rossini, Donizetti and Bellini changed opera completely, producing works that sustain it even today. Bellini was the youngest of the three and his life was the shortest but his contributions were great: Il pirate in 1827, I Capuleti e i Montecchi in1830, La sonnambula a year later, then, in the same 1831, the great Norma and finally I puritani, written in 1835 and premiered in Paris just months before Bellini’s death. In our library we have several Bellini samples but none from Il Pirata. It was written while Bellini was living Milan; the La Scala premier was a great success. Here’s the final scene. Maria Callas is Imogene; the recoding was made in 1958 when Callas was past her absolute prime. Still this is better than anything we can hear being performed these days. The Philharmonia orchestra is led by Nicola Rescigno.

the reasons are purely technical, we do love a good opera. Even though Bellini lived for just 33 years he managed to create several masterpieces that belong to the pantheon of operatic art and have been continuously performed throughout the past 200 years. It’s interesting to note that at the beginning of the 19th century, before Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti produced their major works, Italian opera and composing in general, were not doing well. Opera was born in Italy, and for a century (the 17th, to be exact) Italians were by far the major innovators, even if we consider the talents of Lully, an Italian working in France, and Rameau, the first truly French opera composer. Things changed with George Frideric Handel, a German who absorbed the Italian tradition of Opera Seria and became (in England, of all the places) the major opera composer of his generation. Things shifted to Germany completely by the mid-18th century, with Gluck and especially, Mozart, producing masterpieces above anything else written in the genre. So, when in 1813, Rossini came up with his first major success, L'italiana in Algeri, and then, three years later, created Il barbiere di Siviglia, that ended a drought that lasted for almost 100 years. And in the following 20 years, between the three of them, Rossini, Donizetti and Bellini changed opera completely, producing works that sustain it even today. Bellini was the youngest of the three and his life was the shortest but his contributions were great: Il pirate in 1827, I Capuleti e i Montecchi in1830, La sonnambula a year later, then, in the same 1831, the great Norma and finally I puritani, written in 1835 and premiered in Paris just months before Bellini’s death. In our library we have several Bellini samples but none from Il Pirata. It was written while Bellini was living Milan; the La Scala premier was a great success. Here’s the final scene. Maria Callas is Imogene; the recoding was made in 1958 when Callas was past her absolute prime. Still this is better than anything we can hear being performed these days. The Philharmonia orchestra is led by Nicola Rescigno.

Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck is a Renaissance Dutch composer we’ve never written about, the only excuse being that we don’t know his birthday. Sweelinck was born in Deventer in 1562. Soon after, his family moved to Amsterdam where his father, Pieter, became an organist at Aude Kerk (Old Church), Amsterdam’s oldest building located in what is now Amsterdam’s red-light district. The church has the largest wooden vault in Europe, which creates wonderful acoustics. Pieter died in 1577 and the 15-year old Jan Pieterszoon took his place. He served as the organist at Aude Kerk for the rest of his uneventful life. Sweelinck had many pupils, who eventually became influential organists in the Netherlands and northern Germany. Even though he never travelled to Italy (one of the few major composers not to have done so) or anywhere else, he was clearly familiar with the contemporary Italian and English music. Sweelinck was famous for his improvisations: foreigners were brought to his church to hear him play. Sweelinck wrote many keyboard compositions, none of which, were printed during his lifetime. What was published in large numbers were his choral works. Curiously, none of the text are in Dutch – all are set in French. Here, for example, are his setting of Psalm 150 (Or soit loué l'Eternel) and Psalm 53 (Le fol malin). Both are performed by the Netherlands Chamber Choir under the direction of Peter Phillips.

Permalink