Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

June 20, 2016. The brothers Marcello. Benedetto Marcello was born on June 24th of 1686 in Venice. Of a noble family, he was a younger brother of Alessandro, also a composer. Benedetto followed in Alessandro’s steps, becoming a member of the Grand Council of Venice at the age of 20. Their father wanted Marcello to study law and Benedetto obliged. In 1711 he became a member of the Council of Forty, the government of Venice. In 1730 he was sent as a governor to Pula, Istria, then a territory of the Venetian Republic, now part of Croatia. Eight years later he returned to Italy, in rather poor health, and was hired by the city of Brescia as chief financial officer. He died a year later, in 1739, of tuberculosis.

age of 20. Their father wanted Marcello to study law and Benedetto obliged. In 1711 he became a member of the Council of Forty, the government of Venice. In 1730 he was sent as a governor to Pula, Istria, then a territory of the Venetian Republic, now part of Croatia. Eight years later he returned to Italy, in rather poor health, and was hired by the city of Brescia as chief financial officer. He died a year later, in 1739, of tuberculosis.

Benedetto studied music from an early age; among his teachers was Francesco Gasparini, a well-known composer and teacher (Johann Sebastian Bach was familiar with Gasparini’s compositions). Though a prolific composer, he never held a musical appointment, which put him in a different category compared to professional musicians: in Italy there was a clear social separation between “maestri” and “dilettanti.” That didn’t stop him from being one of the most influential composers of his time. One of Benedetto’s major works was the setting of psalms he called “Estro-poetico armonico.” It was published in eight volumes between 1724 and 1726. Here’s one of the psalms, Mentre io tutta ripongo in Dio, a setting for four voices. It’s performed by the ensemble Cantus Cölln, Konrad Junghänel conducting and playing the lute. In 1731, when he was in Pula, he wrote an oratorio Il piano e il riso delle quattro stagioni dell'anno (Lamentation and Joy of the Four Seasons of the Year). Here’s a Symphony from the oratorio. It’s performed by I Virtuosi delle Muse under the direction of Stefano Molardi.

Some sources say that Alessandro Marcello was born on February 1st, 1673, others have his birthday almost four years earlier, on August 24th, 1669. The latter is more likely, co nsidering that he was admitted to the Grand Council of Venice in 1690: it’s much more probable that he became a member at the age of 21 rather than 17. Highly educated and a man of varied interests, he served as ambassador, was a prolific writer, for a short time indulged in painting and was a talented composer. Alessandro was a member of the prestigious Accademia degli Animosi, the Venetian branch of the Roman Accademia degli Arcadi. He also collected musical instruments, which are now exhibited in Rome, in the National museum of musical instruments. Alessandro wrote a number of cantatas, and also an Oboe concerto, which is often attributed to his brother Benedetto. Johann Sebastian Bach liked it so much that he transcribed it for the harpsichord; in the catalogue of Bach’s works it has number BWV 974. Here’s the original, from Alessandro Marcello. The soloist is Paolo Grazzi, Andrea Marcon is leading the Venice Baroque Orchestra.Permalink

nsidering that he was admitted to the Grand Council of Venice in 1690: it’s much more probable that he became a member at the age of 21 rather than 17. Highly educated and a man of varied interests, he served as ambassador, was a prolific writer, for a short time indulged in painting and was a talented composer. Alessandro was a member of the prestigious Accademia degli Animosi, the Venetian branch of the Roman Accademia degli Arcadi. He also collected musical instruments, which are now exhibited in Rome, in the National museum of musical instruments. Alessandro wrote a number of cantatas, and also an Oboe concerto, which is often attributed to his brother Benedetto. Johann Sebastian Bach liked it so much that he transcribed it for the harpsichord; in the catalogue of Bach’s works it has number BWV 974. Here’s the original, from Alessandro Marcello. The soloist is Paolo Grazzi, Andrea Marcon is leading the Venice Baroque Orchestra.Permalink

June 13, 2016. Gounod, Stravinsky and a Stamitz. Charles Gounod and Igor Stravinsky were born this week, and also Johann Stamitz (père), a Czech-German composer, and the popular Norwegian, Edvard Grieg. Johann Stamitz had two sons, Carl and Anton, Carl being probably the better known of the three, but Johann’s talent shouldn’t be underrated. He was born Jan Václav Stamic (he Germanized the name later in his life) on June 18th or 19th of 1717 in a small town in Bohemia. After studying at the University of Prague he embarked on a career of violin virtuoso. Sometime around 1741 Stamitz was hired by the Mannheim court, which at the time had one of the best orchestras in Germany. Stamitz started as a violinist, then was promoted to the position of Concertmaster and eventually the music director. Stamitz’s responsibilities were to compose orchestral music and conduct; under him the orchestra developed into the most famous ensemble in the world. Some years later the 18-year old Mozart would marvel at their precision and technique. In 1754 Stamitz traveled to Paris and stayed there for a year. In Paris he performed at the Concert Spirituel, the first public concert series in history (the performances took place at the Tuileries Palace, which was burned down during the days of the Paris Commune in 1871). Stamitz returned to Mannheim in the fall of 1755. He died less than two years later at the age of 39. Stamitz composed 58 symphonies and is considered the founding father of the “Mannheim School” of composition, which influenced many composers, including Haydn and Mozart. Here’s one of his symphonies, in A major "Frühling" (“Spring”). Virtuosi di Praga are conducted by Oldřich Vlček.

Jan Václav Stamic (he Germanized the name later in his life) on June 18th or 19th of 1717 in a small town in Bohemia. After studying at the University of Prague he embarked on a career of violin virtuoso. Sometime around 1741 Stamitz was hired by the Mannheim court, which at the time had one of the best orchestras in Germany. Stamitz started as a violinist, then was promoted to the position of Concertmaster and eventually the music director. Stamitz’s responsibilities were to compose orchestral music and conduct; under him the orchestra developed into the most famous ensemble in the world. Some years later the 18-year old Mozart would marvel at their precision and technique. In 1754 Stamitz traveled to Paris and stayed there for a year. In Paris he performed at the Concert Spirituel, the first public concert series in history (the performances took place at the Tuileries Palace, which was burned down during the days of the Paris Commune in 1871). Stamitz returned to Mannheim in the fall of 1755. He died less than two years later at the age of 39. Stamitz composed 58 symphonies and is considered the founding father of the “Mannheim School” of composition, which influenced many composers, including Haydn and Mozart. Here’s one of his symphonies, in A major "Frühling" (“Spring”). Virtuosi di Praga are conducted by Oldřich Vlček.

Charles Gounod was born on June 17th of 1818. He’s rightfully famous for his opera Faust, but he also composed 11 other operas, though none of them at the level of Faust. One of the first operas, Sapho from 1851, was written for his friend, soprano Pauline Viardo, who had recently triumphed in Meyerbeer’s Le prophète. The opera wasn’t successful commercially, but established Gounod as one of the leading young composers. Sapho isn’t staged often these days but some arias are lovely. Here’s the aria Ô ma lyre immortelle in the performance by the wonderful French singer, a soprano-turned-mezzo, Régine Crespin. And of course Je veux vivre from Roméo et Juliette remains popular to this day. Here it is sung by another French singer, the soprano Natalie Dessay.

Also on June 17th but of 1882 Igor Stravinsky was born. We celebrate him every year, and mention him more often than any other composer of the 20th century. Last year we explored Le Baiser de la Fée, his ballet from 1927, commissioned by Ida Rubinstein. At the same time Stravinsky was working on another ballet, Apollo (or Apollon musagète). The commission came from an unusual source, the US Library of Congress. In 1928, Apollo was choreographed first by Adolph Bolm (Ruth Page was one of the muses); that production was quickly forgotten. The same year, the 24-year-old George Balanchine, working for Diagilev’s Ballets Russe, staged Apollo in Paris; the costumes were designed by Coco Chanel, Stravinsky conducted. Apollo became one of his most popular neoclassical pieces. Here it is, performed by the London Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Robert Craft. Robert Craft, a writer and conductor who died a half a year ago, on November 10th of 2015, was one of the people closest to Stravinsky. He recorded practically all of Stravinsky’s orchestral music and wrote several books about the composer, including Conversations with Igor Stravinsky.

Permalink

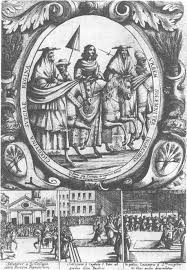

June 6, 2016. Queen Christina, Part II. Christina left Sweden in the summer of 1654; she was 27 years old. She converted to the Catholic faith while in Brussels, and the event was celebrated several weeks later in Innsbruck, under the auspice of Archduke Ferdinand. The festivities, which lasted a whole week, included a performance of L’Argia, an opera by a then very popular composer, Antonio Cesti. Christina’s journey to Rome, with a large entourage and accompanied by cardinals, felt like a triumphal procession. She arrived in Rome just before Christmas of 1655; the Pope Alexander VII received her as if she were a reigning Queen: a royal convert from Protestantism to Catholicism was a big catch for the Papacy. Festivities followed Christina’s arrival, and operas, still new as a genre and very popular in Rome, were at the center: Marco Marazzoli’s Vita humana, dedicated to Christina, an opera by Antonio Tenaglia, and Historia di Abraham et Isaac by Giacomo Carissimi. The staging venues were private palazzos: Palazzo Barberini and Palazzo Pamphilj – as there were no public opera theaters in Rome at the time, those were for Christina to establish.

which lasted a whole week, included a performance of L’Argia, an opera by a then very popular composer, Antonio Cesti. Christina’s journey to Rome, with a large entourage and accompanied by cardinals, felt like a triumphal procession. She arrived in Rome just before Christmas of 1655; the Pope Alexander VII received her as if she were a reigning Queen: a royal convert from Protestantism to Catholicism was a big catch for the Papacy. Festivities followed Christina’s arrival, and operas, still new as a genre and very popular in Rome, were at the center: Marco Marazzoli’s Vita humana, dedicated to Christina, an opera by Antonio Tenaglia, and Historia di Abraham et Isaac by Giacomo Carissimi. The staging venues were private palazzos: Palazzo Barberini and Palazzo Pamphilj – as there were no public opera theaters in Rome at the time, those were for Christina to establish.

Christina herself was initially installed inside the Vatican but a few weeks later moved into one of the most magnificent palazzos of Rome, Palazzo Farnese. Immediately she became the center of the intellectual life of Rome. She established Wednesdays as a day when the palazzo was opened to the nobility and artists to enjoy conversation and good music; a circle of friends that was formed early in 1656 eventually became the Accademia degli Arcadi, a literary academy which survives (as Accademia Letteraria Italiana) to this day. Over the following three and a half centuries, Popes, heads of state, musicians and poets were members. Christina stayed in Rome till September of that year, when she departed for France: France and Spain were contesting the control of Naples, and Christina, whose income was cut by the Swedes since her conversion, needed money. Her goal was to become the Queen of Naples, become financially independent and acquire a role in European politics. She stayed in France for almost two years, first greeted warmly by both Mazarin, the Chief Minister to King Lois XIV and the King himself but eventually wearing out her welcome. Without achieving anything politically, she returned to Rome in 1568 to a much cooler welcome.

She eventually settled in Palazzo Riario (now Corsini) in the Trastevere section of Rome, next to Palazzo Farnesina. She remained there for the rest of her life, save for short trips to Sweden again and Hamburg. She continued collecting art and her collection of Venetian masters was considered unsurpassed. She created a theater in her palace, and in 1667 helped to rebuild Teatro Tor di Nona, which became the first public opera theater in Rome. Her friends included the best painters (Gian Lorenzo Bernini among them) and poets of Rome, and above all, musicians. Major composers dedicated operas to her (Bernardo Pasquini, for example, and Alessandro Stradella), Giacomo Carissimi led her orchestra for a while, Arcangelo Corelli became one of her musicians (and also dedicated several of his compositions to her), and the 18 year-old Alessandro Scarlatti attracted her attention and became her Maestro di Capella. Christina wrote an autobiography (unfinished) and many essays on history and arts. She continued to be active in politics, proclaiming, for example, that Roman Jews were under her protection. In February of 1689 she fell ill and died on April 19th of 1689 at the age of 62. The Pope (Innocent XI, the fourth Pope during Christina’s time in Rome), ordered an official burial. Her body laid in state for four days and then was buried in the Saint Peter Basilica. Her books became part of the Vatican library; her collection of paintings became part of the famous Orleans Collection, which was eventually dispersed around Europe.

The engraving above (by Orazio Marinari) depicts her first, triumphal, entrance into Rome in 1655. She’s flanked by cardinals Orsini and Costaguti.Permalink

May 30, 2016. Queen Christina – Part I. The 17th century was a time of great art and its glorious patrons, and Rome was the center of it all – art, music, riches, and patronage. We’ve written about one of the major figures of the time - Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni, but Queen Christina of Sweden, the benefactress of Giacomo Carissimi, Alessandro Stradella, Bernardo Pasquini, Arcangelo Corelli, Alessandro Scarlatti and so many others, was the one who set the example for all the powerful men that followed in her steps as major patrons of arts. Christina was an extraordinary person, unconventional in every possible way: socially, religiously, sexually, and artistically. She was born on December 18th of 1626 in Stockholm to Gustav II Adolf, King of Sweden. Her father, a great military leader who ably commanded the Swedish army during the Thirty Year War, made sure that she would inherit the throne in case of his death and that she was given extensive tutoring, ordinarily provided only to princes. In 1632 Gustav II was killed in battle and at the age of six Christina became Queen regnant. She eagerly continued her studies, learning Latin and Greek (eventually she learned eight more languages, including French and Italian, both of which she knew perfectly, German, Arabic and even Hebrew). She studied for10 hours a day and seemed to enjoy it. Philosophy and religion were her favorite subjects, and also history and mathematics. “She was not like a female,” was the judgment of one of her courtiers. Intellectually curious, the young Christina invited scholars and philosophers to the court; one of the visitors was a Portuguese rabbi and kabbalist, Menasseh ben Israel. With her guests, she discussed astronomy, theology and natural sciences. She even invited the celebrated French philosopher René Descartes, who came to Stockholm in 1649. They would meet every day, at 5 o’clock in the morning and talk for hours. The tasking schedule and drafty rooms affected Decartes’ health, four months later he caught a cold and died. Christina, who loved the theater (Pierre Corneille’s plays especially) was an amateur actress, and ordered to set one of the palace halls as a theater. In 1648 she invited the famous Flemish painter Jacob Jordaens to create 35 paintings for one of her castles. Around that time, she became one of the biggest collectors of art in Europe. Even though she was yet to get involved with music, these rather costly activities presaged her life as a major patron of arts later on, in Rome.

powerful men that followed in her steps as major patrons of arts. Christina was an extraordinary person, unconventional in every possible way: socially, religiously, sexually, and artistically. She was born on December 18th of 1626 in Stockholm to Gustav II Adolf, King of Sweden. Her father, a great military leader who ably commanded the Swedish army during the Thirty Year War, made sure that she would inherit the throne in case of his death and that she was given extensive tutoring, ordinarily provided only to princes. In 1632 Gustav II was killed in battle and at the age of six Christina became Queen regnant. She eagerly continued her studies, learning Latin and Greek (eventually she learned eight more languages, including French and Italian, both of which she knew perfectly, German, Arabic and even Hebrew). She studied for10 hours a day and seemed to enjoy it. Philosophy and religion were her favorite subjects, and also history and mathematics. “She was not like a female,” was the judgment of one of her courtiers. Intellectually curious, the young Christina invited scholars and philosophers to the court; one of the visitors was a Portuguese rabbi and kabbalist, Menasseh ben Israel. With her guests, she discussed astronomy, theology and natural sciences. She even invited the celebrated French philosopher René Descartes, who came to Stockholm in 1649. They would meet every day, at 5 o’clock in the morning and talk for hours. The tasking schedule and drafty rooms affected Decartes’ health, four months later he caught a cold and died. Christina, who loved the theater (Pierre Corneille’s plays especially) was an amateur actress, and ordered to set one of the palace halls as a theater. In 1648 she invited the famous Flemish painter Jacob Jordaens to create 35 paintings for one of her castles. Around that time, she became one of the biggest collectors of art in Europe. Even though she was yet to get involved with music, these rather costly activities presaged her life as a major patron of arts later on, in Rome.

At the age of nine Christina, after reading the biography of the English Queen Elisabeth, decided that she will not marry. She wrote about “distaste for marriage” in her unfinished autobiography. At the age of 23 she made an official announcement, and asked that her cousin Charles be appointed heir to the throne. For a Queen, she lived a very unusual life: studied all the time, slept just three - four hours a day, and often wore men’s clothes and shoes “for convenience (later in her life in Rome, though, she would wear dresses with such décolleté that even the Pope rebuked her). At the time, her closest friend was her lady-in-waiting, Ebba Sparre, with whom she was probably intimate. In 1651, totally exhausted, she suffered what probably was a nervous breakdown. Her French doctor banned all studies and ordered entertainment instead. Surprisingly, Christina took his advice to heart and abandoning her ascetic lifestyle.

While Sweden was Protestant, since an early age Christina had been interested in Catholicism. One of her confidants was Antonio Macedo, a Portuguese Jesuit. She developed plans to convert. Her unwillingness to marry and Catholicism were clearly conflicting with her position as Queen. In June of 1654 she abdicated in favor of her cousin, Charles Gustav. Few days later she left the country, first to Hamburg, then Antwerp and eventually Rome.Permalink

May 20, 2016. Franz Liszt, Venezia e Napoli. Today we’ll publish an article on Liszt’s Venezia e Napoli, a revision of the earlier set by the same name, which was published as a supplement to the Deuxième année: Italie. We’ll illustrate Gondoliera with a performance by the young Korean-American pianist Woobin Park, Canzone – by a 1985 recording made by the great Jorge Bolet, when he was 71, and Tarantella – with a performance by another young pianist, the American Heidi Hau. ♫

The cities of Venice and Naples must have made a particular impression upon Franz Liszt during his travels with Marie d’Agoult, for, beside the several pieces that would ultimately become the travelogue of his journeys through Italy in the second volume of Années de pèlerinage, he also composed in 1840 a further four pieces named after them—Venezia e Napoli. Like Années de perinage, Venezia e Napoli likewise underwent a significant process of revision once Liszt was in Weimar. Of the original four pieces, only the last two were kept: the Andante placido, which became Gondoliera; and the Tarantelles Napolitaines, which was simply renamed Tarantella. Liszt then inserted a doleful Canzone between these two pieces, creating the triptych now known today. It was published as a supplement to Deuxième Année in 1861.

during his travels with Marie d’Agoult, for, beside the several pieces that would ultimately become the travelogue of his journeys through Italy in the second volume of Années de pèlerinage, he also composed in 1840 a further four pieces named after them—Venezia e Napoli. Like Années de perinage, Venezia e Napoli likewise underwent a significant process of revision once Liszt was in Weimar. Of the original four pieces, only the last two were kept: the Andante placido, which became Gondoliera; and the Tarantelles Napolitaines, which was simply renamed Tarantella. Liszt then inserted a doleful Canzone between these two pieces, creating the triptych now known today. It was published as a supplement to Deuxième Année in 1861.

Liszt based Gondoliera (here), or “Gondolier’s song,” on a well-known melody (“La biondina in gondoletta”) composed by Giovanni Battista Peruchini, an Italian composer born in 1784. Unlike the original version, the 1859 revision opens with an extended introduction in the key of F-sharp minor. Undulating eighth notes in compound meter begin quietly in the bass and slowly rise towards the tonic. In the treble, glistening arpeggios instantly conjure the imagery of a peaceful Venetian canal. Eventually gaining an F-sharp major chord, the music pauses before the commencement of the melody. Marked sempre dolcissimo, the melody, in its first statement, sings out in the rich middle register of the piano above a tonic pedal suggested by the eighth notes still present in the bass. Two more statements follow, each separated by a brief fantasia in Liszt’s usual florid style. Only the latter half of the melody is present in the second statement, but is otherwise only slightly changed. The eighth notes of the bass, however, have now become sixteenths, imbuing the music with an increasing energy. The final statement, on the other hand, is greatly embellished. The melody, still essentially unaltered, now appears against a glimmering accompaniment of trills and broken chords, as if the gondola has suddenly emerged from between two buildings and brilliant sunlight now reflects off the surrounding waters. The melody is repeated again, now below the accompanimental arpeggios, and with its penultimate measure trailing off into a final passage of filigree. From there, the lengthy coda turns the melody somewhat wistful, as its strains are broken up and the minor key creeps back into the tonal fabric. On a stunningly beautiful passage in which full-voice chords move about a fixed F-sharp and A-sharp, the music fades away, like the empty gondola slowly receding from its former passenger. (Read more here).Permalink

May 16, 2016. Wagner and more. Richard Wagner was born on May 22nd of 1813. Last year we wrote about his life around the time he created Tannhäuser. The premier of Lohengrin, the third of his so-called Romantic operas, followed five years later in 1850, although Wagner had started working on it several years earlier, in the mid-1840s. Wagner was still living and working in Dresden, where he was the Kapellmeister at the court of the King of Saxony. Before writing the libretto of Lohengrin, Wagner immersed himself in the old German epics, Parzival, by Wolfram von Eschenbach and Lohengrin; both written in the 13th century (the study of Parzival resulted, some 30 years later, in Wagner writing an idiosyncratic libretto for his last opera, Parsifal). The protagonist, Lohengrin, is the son of Parzival/Parsifal, one of King Arthur's Knights of the Round Table. Lohengrin is sent to rescue a certain maiden, and he undertakes the journey in a boat pulled by swans. The legend, used by Eschenbach to write his epics, originated around the time of the Crusades, so the great Minnesingers, born around 1160, worked with what may be considered “fresh material.” Wagner was still working on the opera when the 1848 insurrections in Paris and Vienna were followed by disturbances in all major cities of Europe. A year later, the left-leaning Wagner became politically active during the troubles in Dresden. As Prussian troops took over the city in May of 1849, Wagner fled to Weimar where he was sheltered for a while by Franz Liszt and then left for Zurich. He stayed out of Germany till 1860. It was Liszt, his future father-in-law, who directed the premier of Lohengrin in Weimar in August of 1850. The opera was a huge success, and not just in Germany – Riga, Vienna, Paris, St.-Petersburg premiers followed during the next several years. Unfortunately, 1850 was also the year when Wagner wrote his infamous article, Das Judenthum in der Musik (Jewishness in Music, often translated as Judaism in Music). Antisemitic and unfair (the article denigrates both Meyerbeer and Mendelssohn) it’s an utter embarrassment, especially considering the influence it had on the murderous anti-Semites of the following years. But going back to the music – Lohengrin, despite its usual Wagnerian length (at about 3 ½ hours, it’s actually among his shortest), is a wonderful opera. Here is the prelude to Act 1, performed by the Berlin Philharmonic, Herbert von Karajan conducting.

Romantic operas, followed five years later in 1850, although Wagner had started working on it several years earlier, in the mid-1840s. Wagner was still living and working in Dresden, where he was the Kapellmeister at the court of the King of Saxony. Before writing the libretto of Lohengrin, Wagner immersed himself in the old German epics, Parzival, by Wolfram von Eschenbach and Lohengrin; both written in the 13th century (the study of Parzival resulted, some 30 years later, in Wagner writing an idiosyncratic libretto for his last opera, Parsifal). The protagonist, Lohengrin, is the son of Parzival/Parsifal, one of King Arthur's Knights of the Round Table. Lohengrin is sent to rescue a certain maiden, and he undertakes the journey in a boat pulled by swans. The legend, used by Eschenbach to write his epics, originated around the time of the Crusades, so the great Minnesingers, born around 1160, worked with what may be considered “fresh material.” Wagner was still working on the opera when the 1848 insurrections in Paris and Vienna were followed by disturbances in all major cities of Europe. A year later, the left-leaning Wagner became politically active during the troubles in Dresden. As Prussian troops took over the city in May of 1849, Wagner fled to Weimar where he was sheltered for a while by Franz Liszt and then left for Zurich. He stayed out of Germany till 1860. It was Liszt, his future father-in-law, who directed the premier of Lohengrin in Weimar in August of 1850. The opera was a huge success, and not just in Germany – Riga, Vienna, Paris, St.-Petersburg premiers followed during the next several years. Unfortunately, 1850 was also the year when Wagner wrote his infamous article, Das Judenthum in der Musik (Jewishness in Music, often translated as Judaism in Music). Antisemitic and unfair (the article denigrates both Meyerbeer and Mendelssohn) it’s an utter embarrassment, especially considering the influence it had on the murderous anti-Semites of the following years. But going back to the music – Lohengrin, despite its usual Wagnerian length (at about 3 ½ hours, it’s actually among his shortest), is a wonderful opera. Here is the prelude to Act 1, performed by the Berlin Philharmonic, Herbert von Karajan conducting.

And now to a somewhat disappointing discovery. Maria Theresia von Paradis was born on May 15th of 1759. We always thought that she was famous for three things: being blind but creative in the age when that was so difficult; for Mozart writing a concerto for her, and the Sicilienne, a wonderful little piece, especially as played by Jacqueline du Pré (here). Unfortunately, the Groves Dictionary suggests that it was not Paradis who was the author of the piece but the purported “discoverer,” the violinist Samuel Dushkin, who arranged the music based on the violin sonata by Carl Maria von Weber and called it Sicilienne. And indeed, if you listen to the second movement of Weber’s Sonata op. 10 no. 1 (here, as played by Leonid Kogan and Grigory Ginsburg), there cannot be any doubt as to the source of the music. Dushkin, a wonderful violinist who worked extensively with Stravinsky and created a number of arrangement, is known to be an author of at least one other “musical hoax”: the so-called Grave for violin and orchestra by Johann Georg Benda, which had nothing to do with the 18th century Bohemian violinist and composer.Permalink