Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

September 12, 2016. Frescobaldi, Cherubini and Schoenberg. Girolamo Frescobaldi, one of the first great keyboard composers, was born on or around September 13th of 1583. We posted a rather detailed entry about him two years ago, so this time we’ll present some of his compositions. As we mentioned, Frescobaldi, even though he wrote in different genres was best known for his works for the keyboard. At the beginning of the 17th century, the keyboard meant the organ or the harpsichord. One of the major collections of organ pieces Frescobaldi wrote late in his life is called Fiori musicali ("Musical Flowers"). It was published in 1635 in Rome; at the time Frescobaldi was working as the organist at St Peter’s Basilica, a prestigious position. Fiori musicali consists of three masses: Missa della Domenica (Sunday Mass), Missa degli Apostoli ("Mass of the Apostles") and Missa della Madonna ("Mass of the Virgin"). At that time, the organ mass was still in development: most masses were choral works. Frescobaldi’s organ setting became highly influential; Henry Purcell studied it, Johann Sebastian Bach copied the whole set by hand. None of the masses cover the complete service; all three start with a Toccata, to be played before the mass. A polyphonic Kyrie section follows, and then a rendition of Credo (written as a Ricercar) and another Toccata. Here’s the third Mass, Missa della Madonna, performed by the organist Roberto Loreggian. About 20 years earlier, in 1615, Frescobladi had published a book of keyboard pieces called “Primo libro di toccata” or the first book of toccatas. The toccatas (there are 12 of them) can be played on the organ or on a harpsichord. Here’s Toccata Prima, played on the harpsichord by Laura Alvini.

detailed entry about him two years ago, so this time we’ll present some of his compositions. As we mentioned, Frescobaldi, even though he wrote in different genres was best known for his works for the keyboard. At the beginning of the 17th century, the keyboard meant the organ or the harpsichord. One of the major collections of organ pieces Frescobaldi wrote late in his life is called Fiori musicali ("Musical Flowers"). It was published in 1635 in Rome; at the time Frescobaldi was working as the organist at St Peter’s Basilica, a prestigious position. Fiori musicali consists of three masses: Missa della Domenica (Sunday Mass), Missa degli Apostoli ("Mass of the Apostles") and Missa della Madonna ("Mass of the Virgin"). At that time, the organ mass was still in development: most masses were choral works. Frescobaldi’s organ setting became highly influential; Henry Purcell studied it, Johann Sebastian Bach copied the whole set by hand. None of the masses cover the complete service; all three start with a Toccata, to be played before the mass. A polyphonic Kyrie section follows, and then a rendition of Credo (written as a Ricercar) and another Toccata. Here’s the third Mass, Missa della Madonna, performed by the organist Roberto Loreggian. About 20 years earlier, in 1615, Frescobladi had published a book of keyboard pieces called “Primo libro di toccata” or the first book of toccatas. The toccatas (there are 12 of them) can be played on the organ or on a harpsichord. Here’s Toccata Prima, played on the harpsichord by Laura Alvini.

Another Italian, Luigi Cherubini lived and worked two centuries after Frescobaldi. He was born on September 14th of 1760 (although some sources state September 8th as his birthday) in Florence. A child prodigy, he studied counterpoint at an early age and also played the harpsichord. When he was thirteen, he composed sections of a Mass and a cantata. He received the Grand Duke’s scholarship to study in Milan and Bologna. During those years he composed several operas (throughout his career he wrote more than 30). In 1785 he traveled to London and then to Paris, where he was presented to Queen Marie Antoinette. The following year, he permanently moved to Paris, where he shared an apartment with his friend and great violinist Giovanni Battista Viotti. Viotti helped him to be appointed the director of Théâtre Feydeau, then called Théâtre de Monsieur, under whose patronage it was created (“Monsieur,” the Count of Provence, the grandson of Louis XV, would become Louis XVIII and reign after the fall of Napoleon, till 1824). Cherubini composed a number of successful operas, presented either at his theater or at the Opéra-Comique (the two theaters would eventually merge). The French Revolution affected Cherubini, as he was associated with the royal family, and at some point he even had to flee Paris, but eventually Napoleon extended him his patronage, however reluctantly (he didn’t like Cherubini’s music). Eventually Cherubini moved away from opera and toward liturgical music. He wrote several masses and a Requiem in C minor, to commemorate the execution of Louis XVI. The Requiem was highly praised by Beethoven and later by Schumann and Brahms (Beethoven held Cherubini in especially high regard, considering him his most talented contemporary). Twenty years later, Cherubini wrote another requiem, in D minor, to be performed at his funeral. Here’s the overture to one of Cherubini’s most successful operas, Les Deux Journées (Two days). Christoph Spering conducts the Neues Berliner Kammerorchester.

Arnold Schoenberg, one of the most influential composer of the first half of the 20th century, was also born this week, on September 13th of 1874. We’ll write about him another time.

PermalinkSeptember 5, 2016. Rare week. Practically every day of this week we could celebrate a birthday of an interesting composer, and on some days more than one. Too much to write in detail, but we’ll mention many. September 5th is especially bountiful – no less than five composers share their birthdays on that day. Johann Christian “the London” Bach, the youngest son of Johann Sebastian and a fine composer, was born on this day in 1735. Anton Diabelli, an Austrian music publisher and composer was born on the same day in 1781. Diabelli is remembered for a very different reason. He had an interesting idea: he wrote a theme and then asked important (mostly Austrian) composers to write one variation, which he then collected and published. For that purpose he composed an unpretentious waltz in C-Major. 51 composers responded, Schubert, Czerny, Hummel, and Moscheles among them. The 12-year old Liszt also submitted an entry (Diabelli didn’t ask him directly, but Czerny, Liszt’s teacher, was eager to demonstrate his student’s talents). One composer responded on a different scale: Beethoven came up not with one but with 33 variations, which became known as Diabelli Variations. Beethoven’s last composition for piano, op. 120 is one of the most profound pieces in piano literature (when played well -- when played poorly, it’s a bore).

this day in 1735. Anton Diabelli, an Austrian music publisher and composer was born on the same day in 1781. Diabelli is remembered for a very different reason. He had an interesting idea: he wrote a theme and then asked important (mostly Austrian) composers to write one variation, which he then collected and published. For that purpose he composed an unpretentious waltz in C-Major. 51 composers responded, Schubert, Czerny, Hummel, and Moscheles among them. The 12-year old Liszt also submitted an entry (Diabelli didn’t ask him directly, but Czerny, Liszt’s teacher, was eager to demonstrate his student’s talents). One composer responded on a different scale: Beethoven came up not with one but with 33 variations, which became known as Diabelli Variations. Beethoven’s last composition for piano, op. 120 is one of the most profound pieces in piano literature (when played well -- when played poorly, it’s a bore).

Three more composers were born on the same day: Giacomo Meyerbeer, who in the mid-19th century was the most popular opera composer in Europe, and two Americans: Amy Beach, born in 1867, and John Cage, in 1912.

Then on September 6th comes the birthday of Isabella Leonarda, who was born in 1620 in Novara, a town west of Milan. When she was 16, the entered a convent and remained there for the rest of her life (she died in the convent at the age of 84, in 1704). Therefore, no interesting events in her life to report. Even though it’s said that she hadn’t started composing till the age of 50, she wrote more than 200 compositions. Her music was well known in Novara but not much in the rest of Italy. Here’s her Sonata Duodecima from 1693 for violin and continuo, performed by the violinist Riccardo Minasi and the ensemble with a whimsical name Bizzarrie Armoniche.

On September 7th we celebrate the birthday of Hernando de Cabezón, born in Madrid around that date in 1541 (we know that he was baptized on the 7th). Hernando was the son of Antonio de Cabezón, also a composer. In 1563 Hernando was appointed organist at Sigüenza Cathedral and stayed there till July of 1566, when his father died and he took his place as the organist to the King Philip II. The King presided over the Golden Age of Spain, when the empire reached its zenith in influence and size. Here’s a song called O bella, from a collection of music compiled by one Octavius Fugger. It’s performed by the French ensemble Charivari Agréable.

September 8th marks the 175th anniversary of the birth of Antonin Dvořák. One of the greatest Czech composers, he excelled as a symphonist; he also wrote chamber music and nine operas, one of which, Rusalka, remains very popular to this day. Here’s his Piano Quintet, op. 81, performed by Quintessence Piano Quintet. Two Englishmen follow, Henry Purcell on the 10th – he was born in 1659, and William Boyce on the 11th of September (Boyce was born in 1711). Purcell, who died tragically young at the age of 36, was one of the greatest English composers of all time. Here’s his When I am laid in earth, from Dido and Aeneas. Jessye Norman is the soprano; English Chamber is conducted by Raymond Leppard. And of course we should remember that Arvo Pärt was also born on the 11th, in 1935.Permalink

August 29, 2016. Bruckner’s Third Symphony. Next Sunday, September 4th, is the birthday of Anton Bruckner, who was born in 1824. The last two years we've celebrated this date with presentations of his Fourth and Fifth symphonies. This time we’ll jump back several years and talk about what many consider his breakthrough work, Symphony no. 3. We had mentioned Bruckner’s notorious lack of confidence, his tendency to rewrite compositions over and over again. In this sense, the Third Symphony is one of the worst examples: there are six different editions of it. The first version was written in 1873. At the time Bruckner was living in Vienna, where he had moved to five years earlier from Linz. He assumed a teaching position at the Vienna Conservatory and became the organist at the Court Chapel, a prestigious but unpaid position. That year Bruckner, who adored Richard Wagner, visited him in Bayreuth and showed him the manuscripts of two symphonies, the Second and the Third, the latter still not complete. Bruckner asked Wagner which one he liked better. Wagner picked the Third, and Bruckner dedicated the symphony to him. The symphony was premiered four years later, the first performance taking place in Vienna on December 16th of 1877. By all accounts, it went badly. The conductor who was supposed to lead the orchestra, one Johann von Herbeck, died unexpectedly on October 28th of that year. Bruckner himself had to step in. He was a decent choral director but quite inexperienced with large symphony orchestras. The Third is about one hour long; the orchestra wasn’t playing well, the public was leaving in droves and by the Finale the hall was almost empty. To make matters worse, Eduard Hanslick, the influential Viennese music critic, a Brahms supporter and Wagner’s detractor, followed the performance with a scathing review. Not everybody disliked the Symphony, however: Mahler, for one, thought enough of it to arrange it for two pianos.

and Fifth symphonies. This time we’ll jump back several years and talk about what many consider his breakthrough work, Symphony no. 3. We had mentioned Bruckner’s notorious lack of confidence, his tendency to rewrite compositions over and over again. In this sense, the Third Symphony is one of the worst examples: there are six different editions of it. The first version was written in 1873. At the time Bruckner was living in Vienna, where he had moved to five years earlier from Linz. He assumed a teaching position at the Vienna Conservatory and became the organist at the Court Chapel, a prestigious but unpaid position. That year Bruckner, who adored Richard Wagner, visited him in Bayreuth and showed him the manuscripts of two symphonies, the Second and the Third, the latter still not complete. Bruckner asked Wagner which one he liked better. Wagner picked the Third, and Bruckner dedicated the symphony to him. The symphony was premiered four years later, the first performance taking place in Vienna on December 16th of 1877. By all accounts, it went badly. The conductor who was supposed to lead the orchestra, one Johann von Herbeck, died unexpectedly on October 28th of that year. Bruckner himself had to step in. He was a decent choral director but quite inexperienced with large symphony orchestras. The Third is about one hour long; the orchestra wasn’t playing well, the public was leaving in droves and by the Finale the hall was almost empty. To make matters worse, Eduard Hanslick, the influential Viennese music critic, a Brahms supporter and Wagner’s detractor, followed the performance with a scathing review. Not everybody disliked the Symphony, however: Mahler, for one, thought enough of it to arrange it for two pianos.

Bruckner started revising the symphony almost as soon as he finished it. In 1874 he created the first revision, mostly by re-orchestrating parts of it. Then, in 1876, he rewrote the second movement, Adagio. Another version followed in 1877 – that’s the version Bruckner gave to Mahler who used it for his two-piano arrangement. By mid-1880s Bruckner’s music became more acceptable. The Third Symphony was performed in several German cities and in the Netherlands, and was brought to New York (it was performed at the old Metropolitan Opera house). That didn’t stop Bruckner from tinkering with it. In 1889, twelve years after the premier, he returned to the Third and created another edition, and then, just one year later, yet another one. The version we’ll hear is from 1889. The Munich Philharmonic Orchestra is conducted by one of the most interesting interpreters of the music of Bruckner, the Romanian-born Sergiu Celibidache who at the time was the Principal conductor of the Munich Philharmonic. As are all Bruckner’s symphonies, the Third is in four parts. The first movement Gemäßigt, mehr bewegt, misterioso (Moderate, more animated, mysterious) runs about 25 minutes (here); the second, Adagio, sixteen and a half (here); the third, Scherzo, is just shy of eight minute (here), and Finale, Allegro (here), is about 15 minutes long.Permalink

August 22, 2016. Debussy and Stockhausen. Claude Debussy, one of the greatest composers of the late 19th – early 20th century, was born in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, a suburb of Paris, on this day in 1862. We’ve written about Debussy many times (here and here, for example) and usually illustrated his art with pieces written in the more popular genres – symphonic music and, especially, piano music. That somewhat skews the perspective: Debussy was prolific as a chamber composer, he wrote a large number of wonderful songs, and ever composed several operas, although he finished only one of them, Pelléas et Mélisande. Pelléas was written in 1902 on the libretto adapted from the namesake play by Maurice Maeterlinck. Debussy had toyed with the idea of writing an opera on several occasions. In 1890 he accepted a libretto written by a noted poet Catulle Mendès and started on the opera he called Rodrigue et Chimène. Debussy worked on it for the following three years, during which time his own compositional style had changed and he got dissatisfied both with his own music and with the libretto. Debussy abandoned Rodrigue after he saw a performance of Maeterlinck’s Pelléas. (The Opéra de Lyon asked Edison Denisov, the Russian composer blacklisted during the Soviet time, to complete the orchestration of the opera; Rodrigue was premiered in 1993, exactly 100 years after it was abandoned by Debussy). A short version of Pelléas was completed in 1895 but Debussy couldn’t find an opera theater that would commit to staging it. In 1898 André Messager, a composer, conductor and a friend of Debussy’, was made the music director of the Opéra-Comique in Paris. That lead to the premier on April 30th of 1902. The reaction was mixed. The public mostly disapproved, while musicians – friends of Debussy and most of the Conservatory students thought very highly of it. Camille Saint-Saëns, who disliked Debussy’s music in general said that he stayed in Paris, instead of leaving for a summer vacation, so that he could say “nasty things about Pelléas.” Here’s Act 3 of the opera (about 27 minutes of music); Claudio Abbado conducts the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, François Le Roux is Pelléas, Maria Ewing is Mélisande.

day in 1862. We’ve written about Debussy many times (here and here, for example) and usually illustrated his art with pieces written in the more popular genres – symphonic music and, especially, piano music. That somewhat skews the perspective: Debussy was prolific as a chamber composer, he wrote a large number of wonderful songs, and ever composed several operas, although he finished only one of them, Pelléas et Mélisande. Pelléas was written in 1902 on the libretto adapted from the namesake play by Maurice Maeterlinck. Debussy had toyed with the idea of writing an opera on several occasions. In 1890 he accepted a libretto written by a noted poet Catulle Mendès and started on the opera he called Rodrigue et Chimène. Debussy worked on it for the following three years, during which time his own compositional style had changed and he got dissatisfied both with his own music and with the libretto. Debussy abandoned Rodrigue after he saw a performance of Maeterlinck’s Pelléas. (The Opéra de Lyon asked Edison Denisov, the Russian composer blacklisted during the Soviet time, to complete the orchestration of the opera; Rodrigue was premiered in 1993, exactly 100 years after it was abandoned by Debussy). A short version of Pelléas was completed in 1895 but Debussy couldn’t find an opera theater that would commit to staging it. In 1898 André Messager, a composer, conductor and a friend of Debussy’, was made the music director of the Opéra-Comique in Paris. That lead to the premier on April 30th of 1902. The reaction was mixed. The public mostly disapproved, while musicians – friends of Debussy and most of the Conservatory students thought very highly of it. Camille Saint-Saëns, who disliked Debussy’s music in general said that he stayed in Paris, instead of leaving for a summer vacation, so that he could say “nasty things about Pelléas.” Here’s Act 3 of the opera (about 27 minutes of music); Claudio Abbado conducts the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, François Le Roux is Pelléas, Maria Ewing is Mélisande.

And now, as Monty Python would say, for something completely different. Karlheinz Stockhausen was also born on this day, in 1928. A seminal figure of the musical avant-garde of the after-WWII generation, he was praised by some and scorned by others (his electronic music Studie II received the lowest possible score of 1 from one of our listeners). Stockhausen was born in Burg Mödrath, near Cologne. When he was seven the family moved to Altenburg, nearby. His mother had a nervous breakdown and was institutionalized. In 1941 the family received an official letter informing them that she died of leukemia. It was determined later that she was gassed, as were most of the patients of the hospital, as a “useless eater” by the Nazis (Stockhausen will reinterpret this terrible episode in his opera Donnerstag aus Licht. Here’s the opening section of the opera. Karlheinz Stockhausen conducts the brass and percussion players). In 1947 he enrolled at the Cologne Musikhochschule (Conservatory), where he studied composition with Frank Martin. Upon graduating in 1951 he was invited to Darmstadt, the famous Ferienkurse für Neue Musik (Summer courses for new music). There he met several students of Olivier Messiaen and decided that he also needed to take his classes. He went to Paris in 1952, was accepted into Messiaen’s class and studied there for a year. Around that time a new Electronic Music Studio was established in Cologne and Stockhausen joined it in 1952. The new aural world was opening up.Permalink

August 15, 2016. Nicola Porpora. Nicola Porpora, a prolific opera composer, was born in Naples on August 17th of 1686. He was 10 when he enrolled in the Conservatorio dei Poveri di Gesù Cristo. In 1708 he received his first opera commission and wrote L’Agrippina but had to wait several years to get another one. That was probably because Alessandro Scarlatti so thoroughly dominated the Neapolitan opera scene: 1708 was the year the much more famous Scarlatti returned to Naples after six years in Florence and Rome. Porpora was 13 and still at the Conservatory when he started teaching and it’s his teaching talents that he would become famous for, at least as much as for his operas. As there were few opera commissions, he earned money working at the Conservatorio di S Onofrio and giving private lessons. In 1719 Scarlatti returned to Rome and that opened the stage for Porpora. One of the operas composed during that period was Angelica, on the libretto by the young Pietro Metastasio. The role of Orlando was sung by Porpora’s star pupil, the 15-year old castrato Farinelli, who would become one of the most celebrated singers in the history of opera. Among Porpora’s pupils was also Gaetano Majorano, known as Caffarelli, also a castrato, second only to Farinelli; he became one of Handel’s favorite singers. Here’s an aria from Angelica called Ombre amene. The countertenor is Robert Expert; the orchestra of Real Compañia Ópera De Cámara is conducted by Juan Bautista Otero.

Gesù Cristo. In 1708 he received his first opera commission and wrote L’Agrippina but had to wait several years to get another one. That was probably because Alessandro Scarlatti so thoroughly dominated the Neapolitan opera scene: 1708 was the year the much more famous Scarlatti returned to Naples after six years in Florence and Rome. Porpora was 13 and still at the Conservatory when he started teaching and it’s his teaching talents that he would become famous for, at least as much as for his operas. As there were few opera commissions, he earned money working at the Conservatorio di S Onofrio and giving private lessons. In 1719 Scarlatti returned to Rome and that opened the stage for Porpora. One of the operas composed during that period was Angelica, on the libretto by the young Pietro Metastasio. The role of Orlando was sung by Porpora’s star pupil, the 15-year old castrato Farinelli, who would become one of the most celebrated singers in the history of opera. Among Porpora’s pupils was also Gaetano Majorano, known as Caffarelli, also a castrato, second only to Farinelli; he became one of Handel’s favorite singers. Here’s an aria from Angelica called Ombre amene. The countertenor is Robert Expert; the orchestra of Real Compañia Ópera De Cámara is conducted by Juan Bautista Otero.

In 1723-24 Porpora traveled to Vienna and Munich but received no appointments. He returned to Italy and settled in Venice. An intense rivalry developed between him and Leonardo Vinci, who was Porpora’s classmate in Naples. In 1730 Porpora and Vinci produced operas which ran simultaneously in two leading Roman opera houses, one in Teatro della Dame, another – in Teatro Capranica (Teatro della Dame was the largest in Rome when built in 1718, it burned down in 1863; Teatro Capranica, the second oldest public opera house in Rome after the Teatro delle Quattro Fontane, still exists but is mostly used for various public events). In 1730 Vinci died, age 40, and for a while Poprora’s competitive impulse focused on another successful opera composer, Johann Adolph Hasse.

In 1733 Porpora received an invitation from a group of Londoners who were setting up an opera house to rival Handel’s. Porpora traveled to London and stayed there for almost three years. During that time he composed five operas, which were staged at the new opera, called Opera of the Nobility. The first, Arianna in Naxo, turned out to be the most successful one, even though Farinelli made his London debut in the subsequent Polifemo. Porpora left London in 1736, and less than a year later both the Opera of the Nobility and Handel’s opera collapsed. Here’s the wonderful French countertenor Philippe Jaroussky singing the area Alto Giove, from Polifemo. Porpora returned to Italy, splitting his time between Venice and Naples. The opera commissions were drying up, and Porpora traveled to Dresden, where he received an appointment as Kapellmeister at the court of Saxony. That lasted for five years; in 1752 he was sent into retirement and moved to Vienna. There he renewed his friendship with Metastasio; and it was probably Metastasio who introduced the 20-year old Joseph Haydn to Porpora. Haydn, who was trying to make a living as a freelancing pianist and composer, became Porpora’s valet, keyboard accompanist, and student. It seems Porpora treated Haydn pretty roughly, but Haydn later claimed that he learned "the true fundamentals of composition from the celebrated Herr Porpora.” Porpora was living mostly on a pension from Dresden, and when that ended in 1759, he moved back to Naples. He was made maestro di cappella in the Conservatorio di S Maria di Loreto. His final opera was a failure, he had to resign from the conservatory and spent the last years of his life in poverty. Porpora died in Naples on March 3rd of 1768. Here’s the aria Tu che d'ardir' m'accendi from his opera Siface. Again, we’ll hear Philippe Jaroussky, this time with Le Concert d'Astree under the direction of Emmanuelle Haim.Permalink

August 6, 2013. Dufay and the early Renaissance, part 2. Last week we discussed, in broad terms, the period of music that is customarily called “Early Renaissance.” Today we’ll present three famous composers of that period, Dufay, Dunstaple and Binchois. What we find fascinating in their stories is how intertwined the European music culture of the time was, on a personal level and with musical ideas spreading from one country to another. All this in a war-torn Europe, which often seems so static to a contemporary observer.

The most famous Franco-Flemish composer of the mid-15th century, Guillaume Dufay was probably born in 1397. Exactly where is not clear: either around Cambrai, in what is now Northern France, or in Beersel, outside of Brussels. He was an illegitimate child of a local priest. His uncle was a canon at the cathedral of Cambrai, and the young Guillaume became a chorister there. His talents were noticed early on and he was given formal musical training. In 1420 Dufay moved to Rimini to serve at the palace of Carlo Malatesta, a famous condottiero. There he wrote church music – masses and motets – and also secular ballades and rondeaux. Dufay stayed in Malatesta’s service till 1424 and then returned to France, to Cambrai or maybe Laon. In 1426 Dufay went back to Italy, this time into the service of Louis Aleman, a French Cardinal who at that time was a papal legate in Bologna. Two years later Dufay moved to Rome and became a member of the papal choir. He remained in Rome till 1433; by then his fame had spread all around Europe. He left Rome to join the court of Amédée VIII, the duke of Savoy. In 1434 the duke’s son Louis married Ann of Cyprus, and many guests were invited to the wedding. One of them wasPhilip the Good, duke of Burgundy. In the duke’s retinue was Gilles Binchois. Apparently Dufay and Binchois met on that occasion, at least according to Martin le Franc, the same le Franc who coined the term La Contenance Angloise to describe the style of John Dunstaple, another famous contemporary. In 1435 Dufay returned to the papal court, which this time was in Florence, where Pope Eugene IV was driven by an insurrection in Rome. It was in Florence that Dufay composed one of his most famous motets, Nuper Rosarum Flores ("Recently Flowers of Roses"). It was written for the consecration of the Florence cathedral, Santa Maria del Fiore (Saint Mary of the Flowers) on March 25th, 1436. The great architect Filippo Brunelleschi had just completed the magnificent cupola, and the Pope himself presided over the festivities. Dufay returned to Cambrai around 1459 and lived there for the rest of his life, actively composing till the end. His life was a long one, for the time: he died on November 24th of 1474.

Franco-Flemish composer of the mid-15th century, Guillaume Dufay was probably born in 1397. Exactly where is not clear: either around Cambrai, in what is now Northern France, or in Beersel, outside of Brussels. He was an illegitimate child of a local priest. His uncle was a canon at the cathedral of Cambrai, and the young Guillaume became a chorister there. His talents were noticed early on and he was given formal musical training. In 1420 Dufay moved to Rimini to serve at the palace of Carlo Malatesta, a famous condottiero. There he wrote church music – masses and motets – and also secular ballades and rondeaux. Dufay stayed in Malatesta’s service till 1424 and then returned to France, to Cambrai or maybe Laon. In 1426 Dufay went back to Italy, this time into the service of Louis Aleman, a French Cardinal who at that time was a papal legate in Bologna. Two years later Dufay moved to Rome and became a member of the papal choir. He remained in Rome till 1433; by then his fame had spread all around Europe. He left Rome to join the court of Amédée VIII, the duke of Savoy. In 1434 the duke’s son Louis married Ann of Cyprus, and many guests were invited to the wedding. One of them wasPhilip the Good, duke of Burgundy. In the duke’s retinue was Gilles Binchois. Apparently Dufay and Binchois met on that occasion, at least according to Martin le Franc, the same le Franc who coined the term La Contenance Angloise to describe the style of John Dunstaple, another famous contemporary. In 1435 Dufay returned to the papal court, which this time was in Florence, where Pope Eugene IV was driven by an insurrection in Rome. It was in Florence that Dufay composed one of his most famous motets, Nuper Rosarum Flores ("Recently Flowers of Roses"). It was written for the consecration of the Florence cathedral, Santa Maria del Fiore (Saint Mary of the Flowers) on March 25th, 1436. The great architect Filippo Brunelleschi had just completed the magnificent cupola, and the Pope himself presided over the festivities. Dufay returned to Cambrai around 1459 and lived there for the rest of his life, actively composing till the end. His life was a long one, for the time: he died on November 24th of 1474.

Gilles Binchois was born around 1400 in the city of Mons, which is now in Belgium and back then was the capital of the County of Hainaut. It later became part of the Duchy of Burgundy. During the Hundred Years’ War the Burgundians fought on the side of the English, and at some point even captured Paris. It’s known that around 1425 Binchois was in Paris serving William de la Pole, earl of Suffolk and one of the English commanders during the War. Around 1430 Binchois joined the court chapel of Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy and stayed there for many years. Philip loved music and hired many musicians and composers; Guillaume Dufay wrote for him. Philip didn’t have a permanent capital and moved his court between the palaces in Brussels, Bruges, Dijon and other cities of the Duchy; Binchois most likely traveled with the court. Eventually he retired to Soignies, just outside of Mons. He died in 1460. Binchois was considered the finest melodist of the 15th century (although some might argue that this honor belongs to John Dunstaple), and was, with Guillaume Dufay, the most significant composer of the early Burgundian (Franco-Flemish) School.

John Dunstaple was born around 1390 (a conjecture based on the timing of some compositions), probably in the town of Dunstable. He served in the court of John of Lancaster, a son of King Henry IV and a brother of Henry V. John led the British forces in many battles of the Hundred Year War with France (he was the one to capture Joan of Arc) and for a number of years was the Governor of Normandy. It’s likely that Dunstaple stayed with John in Normandy. From there his music spread around the continent. Considering that a major war was raging in France, it is quite remarkable. Dunstaple’s influence was significant, especially affecting musicians of the highly developed Burgundian school; the reason was both musical and political, as Burgundy was allied with England in its war against France. The poet Martin Le Franc, a contemporary of Dunstaple, came up with the term La Contenance Angloise, which could be loosely translated as “English manner” and said that it influenced the two greatest composers of Burgundy, Guillaume Dufay and Gilles Binchois. Le Franc wrote his treaties in 1442, by then Dunstaple was back in England, serving in the court of Humphrey of Lancaster, John’s brother. In addition to writing music, he also studied mathematics, and was an astronomer and astrologer. While not a cleric, he was associated with St. Albans Abbey. Dunstaple died in 1453. During the reign of Henry VIII England became Protestant, many monasteries – the main keepers of musical tradition – were "dissolved" and their libraries were ruined. Most of the English manuscripts of Dunstaple’s music were lost. Fortunately, many copies remained in Italy and Germany – evidence of Dunstaple’s international fame. About 50 compositions are currently attributed to him: two complete masses, a number of sections from masses that are otherwise lost, and many motets.

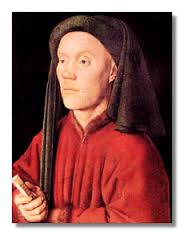

The portrait above, by Jan van Eyck from 1432of an unattributed sitter, is sometimes said to represent Dufay; other believe it to be Binchois.Permalink