Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

May 25, 2015. Chopin’s Waltzes. With apologies to the devotees of the music of Isaac Albéniz, Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Marin Marais, all of whom were born this week, we’re publishing a longer piece by Joseph DuBose on waltzes by Frédéric Chopin. We’ll illustrate each of these concise gems with performances, some by the young artists for whom Classical Connect serves as a virtual concert stage: Bill-John Newbrough, Anastasya Terenkova, Konstantyn Travinsky, Yury Shadrin; others – by the acknowledged masters. You’ll hear the 77 year-old Artur Rubinstein live in Moscow (you can hear him announcing the encore), Evgeny Kissin live in Carnegie Hall, Zoltan Kocsis, Philippe Entremont, the French pianist and conductor, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, Dinu Lipatti in a recording made in 1950, just months before his death at the age of 33; Vladimir Ashkenazy and Samson François in a 1963 recording. ♫

for whom Classical Connect serves as a virtual concert stage: Bill-John Newbrough, Anastasya Terenkova, Konstantyn Travinsky, Yury Shadrin; others – by the acknowledged masters. You’ll hear the 77 year-old Artur Rubinstein live in Moscow (you can hear him announcing the encore), Evgeny Kissin live in Carnegie Hall, Zoltan Kocsis, Philippe Entremont, the French pianist and conductor, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, Dinu Lipatti in a recording made in 1950, just months before his death at the age of 33; Vladimir Ashkenazy and Samson François in a 1963 recording. ♫

The waltz is inextricably connected to that great musical city of Vienna. Thus, when, as a budding composer and pianist, Frederic Chopin made his debut in the city in 1829 soon after his graduation from the Warsaw Conservatory, and again visited in 1830, it is no surprise that he tried to assimilate himself into its musical culture by performing and even composing waltzes. Yet, Chopin’s Polish roots ran too deep, and he was never able to fully master the distinctive waltz style. On his return from the Austrian capital, he admitted to a friend, “I have acquired nothing of that which is specially Viennese by nature, and accordingly I am still unable to play valses.”

Chopin’s earliest waltzes roughly date from the time of his first visit to Vienna. Yet, these early attempts remained unpublished during the composer’s lifetime. Indeed, his first waltz only appeared in print after he had left Vienna for Paris, where he would remain for the rest of his life. Currently, there are eighteen known waltzes that Chopin composed, though it is believed he wrote others. However, only the first fourteen are generally numbered. Of these fourteen, only eight were published during Chopin’s lifetime—opp. 18 and 42, and the two sets of three of opp. 34 and 64. Five more were issued in the decade following Chopin’s death and make up opp. 69 and 70. Finally, two others appeared during the remainder of the 19th century—the well-known E minor waltz in 1868 and another in E major in the early 1870s. (Continue reading here).

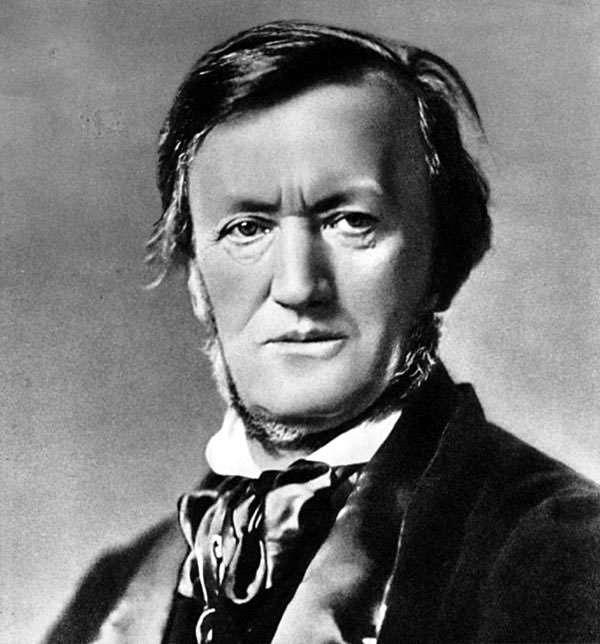

PermalinkMay 18, 2015. Wagner’s Tannhäuser. Richard Wagner was born on May 22nd of 1813. Somehow, this date seems incongruous: was he really just three years younger than Chopin and Schumann? Those are geniuses firmly established in the Pantheon of classical music, while people still argue about Wagner. His music and his writings still can create controversies, as we’ll see in a minute. Wagner was living in Paris when he completed his third and fourth operas, Rienzi and The Flying Dutchman. He approached Giacomo Meyerbeer, a German-Jewish composer who was living in Paris and asked for advice on the staging of Rienzi. Wagner’s letters to Meyerbeer sound almost obsequious, which is worth noticing, considering the events that followed. In the previous decade Meyerbeer had conquered Paris with his own operas, Robert le Diable in particular. Even though he had lived in Paris for many years, Meyerbeer still maintained connections in Germany, which he used to help Wagner, in Dresden with Rienzi and in Berlin with The Flying Dutchman. In 1842 Rienzi was accepted at the Dresden Court Theater and Wagner moved there right away. The opera was premiered in October of that year and proved to be a success, Wagner’s first. A couple years later he was appointed the conductor at the Court Theater. Wagner, whom Meyerbeer not only helped at a critical moment of Wagner’s life, but who also deeply influenced him by his operas, eventually became Meyerbeer’s biggest enemy. He wrote several pamphlets against Meyerbeer, all of them deeply anti-Semitic in nature. But that was to come later. While still in Dresden, Wagner wrote Tannhäuser, an opera on his own libretto, derived from German legends about a 13th-century German minnesinger Henrich Tannhäuser and a certain song contest. Long, convoluted, and at times incoherent, it tells a story of the poet and singer Tannhäuser who lives in the realm of Venus, the goddess of love, surrounded by young beautiful women. After some sexual shenanigans he decides that he’s had enough and returns to real life in Wartburg. There, the local count holds a song contest. Tannhäuser’s love song is considered too profane and he’s banished from Wartburg and ordered to visit the Pope. More fantastic events take place, involving Tannhäuser, his love interest Elisabeth, and his friend Wolfram, with Venus making an appearance and the Pope’s staff flowering at the very end of the opera. None of it makes much sense, but the juxtaposition of Venus and the church, of lust, love and faith gives directors ample opportunity to excersize their fantazy. Modern productions set Tannhäuser in different eras and some use a good doze of nudity and profanity. One such production, rather mild by European standards, was recently created in the Russian city of Novosibirsk. What followed was a rather typical Russian story. The hierarchs of the local Orthodox church rose in protest, and so did the more conservative members of the local society. Demonstrations were staged, accusations were hurled in the media, the courts got involved. And even though some members of the Russian artistic community tried (rather meekly, it has to be said) to defend the production, the minister of culture moved in and sacked the director. Truly, modern Russia is more bizarre than any of Wagner’s librettos.

when he completed his third and fourth operas, Rienzi and The Flying Dutchman. He approached Giacomo Meyerbeer, a German-Jewish composer who was living in Paris and asked for advice on the staging of Rienzi. Wagner’s letters to Meyerbeer sound almost obsequious, which is worth noticing, considering the events that followed. In the previous decade Meyerbeer had conquered Paris with his own operas, Robert le Diable in particular. Even though he had lived in Paris for many years, Meyerbeer still maintained connections in Germany, which he used to help Wagner, in Dresden with Rienzi and in Berlin with The Flying Dutchman. In 1842 Rienzi was accepted at the Dresden Court Theater and Wagner moved there right away. The opera was premiered in October of that year and proved to be a success, Wagner’s first. A couple years later he was appointed the conductor at the Court Theater. Wagner, whom Meyerbeer not only helped at a critical moment of Wagner’s life, but who also deeply influenced him by his operas, eventually became Meyerbeer’s biggest enemy. He wrote several pamphlets against Meyerbeer, all of them deeply anti-Semitic in nature. But that was to come later. While still in Dresden, Wagner wrote Tannhäuser, an opera on his own libretto, derived from German legends about a 13th-century German minnesinger Henrich Tannhäuser and a certain song contest. Long, convoluted, and at times incoherent, it tells a story of the poet and singer Tannhäuser who lives in the realm of Venus, the goddess of love, surrounded by young beautiful women. After some sexual shenanigans he decides that he’s had enough and returns to real life in Wartburg. There, the local count holds a song contest. Tannhäuser’s love song is considered too profane and he’s banished from Wartburg and ordered to visit the Pope. More fantastic events take place, involving Tannhäuser, his love interest Elisabeth, and his friend Wolfram, with Venus making an appearance and the Pope’s staff flowering at the very end of the opera. None of it makes much sense, but the juxtaposition of Venus and the church, of lust, love and faith gives directors ample opportunity to excersize their fantazy. Modern productions set Tannhäuser in different eras and some use a good doze of nudity and profanity. One such production, rather mild by European standards, was recently created in the Russian city of Novosibirsk. What followed was a rather typical Russian story. The hierarchs of the local Orthodox church rose in protest, and so did the more conservative members of the local society. Demonstrations were staged, accusations were hurled in the media, the courts got involved. And even though some members of the Russian artistic community tried (rather meekly, it has to be said) to defend the production, the minister of culture moved in and sacked the director. Truly, modern Russia is more bizarre than any of Wagner’s librettos.

All of this doesn’t really matter: the music of Tannhäuser is great, and gets better as the opera evolves. The third act is magnificent. Here’s an excerpt, with the great German baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, the orchestra of Staatsoper Berlin, Franz Konwitschny conducting.

PermalinkMay 11, 2015. Monteverdi. The great Italian composer Claudio Monteverdi was born this week, on May 15th of 1567. And so were three French composers, Jules Massenet, Gabriel Fauré and Erik Satie: Massenet on May 12th of 1842, Fauré on the same day three years later in 1845 and Satie on May 17th, 1866. We wrote about Massenet and Fauré last year, and the wonderfully whimsical Satie will have to wait for another occasion, as this entry will go to the “father of the Italian opera.”

Here are two episodes from L’Orfeo: first, Rosa del ciel, (Orfeo and Euridice nuptial ceremony) from Act I, with Montserrat Figueras and Furio Zanasi, with Jordi Savall directing Le Concert des Nations; then, aria Tu se' morta from Act II. Georg Nigl is Orfeo. And here’s from the 2010 production of L'incoronazione di Poppea, with the wonderful Danielle de Niese as Poppea and Philippe Jaroussky as Nerone. William Christie conducts Les Arts Florissants.Permalink

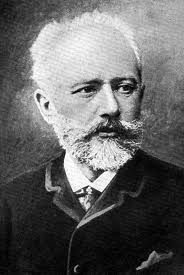

May 4, 2015. Brahms and Tchaikovsky. This is the week when we celebrate two birthdays, that of Johannes Brahms and of Peter Tchaikovsky. Both were born on May 7th: Brahms in 1833, Tchaikovsky – in 1840. Last year we wrote rather extensively about the latter, and heard two first symphonies, the magisterial one by Brahms, which he spent almost 15 years composing (he started working on it in 1862, it was premiered in 1876), and also Tchaikovsky’s First, which is much smaller both in scale and as a musical achievement; it was written in 1866. Тhe comparison wasn’t quite fair, and we did it only because of Tchaikovsky’s incomprehensible disdain for Brahms’s music. Tchaikovsky wrote six symphonies and only the last three represent his talent at its highest level, while all four of Brahms’s symphonies are great. So if we were to continue the parallel, we’d probably have to compare Tchaikovsky’s Fourth with Brahms’s Second, especially considering that they were written practically at the same time: Tchaikovsky’s in 1877-78, while Brahms, after procrastinating over his first, wrote the second in just one summer of 1877.

first symphonies, the magisterial one by Brahms, which he spent almost 15 years composing (he started working on it in 1862, it was premiered in 1876), and also Tchaikovsky’s First, which is much smaller both in scale and as a musical achievement; it was written in 1866. Тhe comparison wasn’t quite fair, and we did it only because of Tchaikovsky’s incomprehensible disdain for Brahms’s music. Tchaikovsky wrote six symphonies and only the last three represent his talent at its highest level, while all four of Brahms’s symphonies are great. So if we were to continue the parallel, we’d probably have to compare Tchaikovsky’s Fourth with Brahms’s Second, especially considering that they were written practically at the same time: Tchaikovsky’s in 1877-78, while Brahms, after procrastinating over his first, wrote the second in just one summer of 1877.

Tchaikovsky composed the Fourth around the time he was recovering from the disastrous marriage to his former student, Antonina Milyukova. Tchaikovsky married Milyukova in July of 1877 (at that time he was working on his opera “Eugene Onegin”). The marriage was hastily arranged. It seems that Tchaikovsky mostly wanted to stop the rumors of his homosexuality; at least that’s what we find in his letter to his brother Modest. But homosexuality was also the reason the marriage turned a devastating failure. In just several weeks Tchaikovsky fled. The whole experience upset him to no end. Despondent, he quit his position at the Moscow Conservatory and set off for Italy. But even in this terrible mental state, he continued to compose, and the Forth symphony was the main work he produced during that period. Most of its themes are either tragic or full of melancholy. Following Beethoven’s Fifth, the first movement is built around the theme of Fate; Tchaikovsky himself spelled out the “program” of the first movement in a letter to his patroness Nadezhda von Meck, writing that fate prevents one from attaining happiness). The reference in the fourth movement%20by%20Lev%20Russov.jpg) to a simple Russian folk song about the birch tree in a field also has melancholy overtones. Even the rousing finale refers to the Fate motive of the first movement. Tchaikovsky was in Florence when the Symphony premiered in Moscow, in February of 1878 with his friend Nikolai Rubinstein conducting. The initial reception was rather negative, not just in Russia but also in the US, Germany and Britain. Soon after, though, opinions changed with the Fourth being acknowledged as Tchaikovsky’s masterpiece and one of the most important Romantic symphonies. We’ll hear it in a taut, unsentimental 1957 performance by the Leningrad Philharmonic under the baton of the great Russian conductor Evgeny Mravinsky. The portrait of Mravinsky, above, was painted by Lev Russov the same year the recording was made, in 1957.

to a simple Russian folk song about the birch tree in a field also has melancholy overtones. Even the rousing finale refers to the Fate motive of the first movement. Tchaikovsky was in Florence when the Symphony premiered in Moscow, in February of 1878 with his friend Nikolai Rubinstein conducting. The initial reception was rather negative, not just in Russia but also in the US, Germany and Britain. Soon after, though, opinions changed with the Fourth being acknowledged as Tchaikovsky’s masterpiece and one of the most important Romantic symphonies. We’ll hear it in a taut, unsentimental 1957 performance by the Leningrad Philharmonic under the baton of the great Russian conductor Evgeny Mravinsky. The portrait of Mravinsky, above, was painted by Lev Russov the same year the recording was made, in 1957.

Brahms’s life during this period was very different. His career was at the summit. Even though some years earlier his First Piano concerto was poorly received, the German Requiem established him as one of the most important European composer. He had recently completed the First symphony, and was invited all around Europe to perform it as the pianist and conductor (he mostly played his own work). He had many friends (Clara Schumann being one of them) and even more admirers. In 1878, for the first time in his life, he went on vacation to Italy, which he described as paradise. Brahms was in Italy practically at the same time as Tchaikovky – but in a very different mood. Somehow this mood affected his Second symphony, so "pastoral" in nature that it was often compared to Beethoven’s Sixth. Here’s Brahm’s Symphony no. 2 in D major, Op. 73, performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Georg Solti conducting.Permalink

April 27, 2015. Alessandro Scarlatti and Leoncavallo. Two wonderful Italian opera composer were born around this time, two centuries apart - Alessandro Scarlatti and Ruggero Leoncavallo. Scarlatti was close to the beginning of the Italian opera, Leoncavallo – at the end of it, or at least that’s how it feels from our vantage point (let’s hope the Italian genius rejuvenates itself in the near future). Alessandro Scarlatti was born on May 2nd of 1660 in Palermo, Sicily (we’ve written about him a number of times, for example here and here). When he was 12, he went to Rome and studied there with Giacomo Carissimi, another seminal figure in the history of Italian opera (Carissimi’s birthday was just several days ago: he was born on April 18th of 1605). Scarlatti wrote his first opera at the age of 19. As so many Roman composers of his time, Scarlatti worked under the patronage of Queen Christina. He then went to Naples to serve at the courts of the Viceroys, who ruled Naples on behalf of the King of Spain. He moved between Naples and Rome for the rest of his life. Scarlatti wrote 115 opera, of which 64 survive. In the process, he came up with a number of innovations, di capo aria being one of them; di capo, a tripartite aria in which the third part repeats the first (di capo meaning “from the head” or from the beginning in Italian), but with improvisations, became a mainstay of the baroque opera. Scarlatti’s last opera, La Griselda, was written in 1721. Here’s the aria In voler cio che tu brami... Che arrechi, Ottone. It’s sung by the wonderful Italian soprano Mirella Freni; Nino Sanzogno conducts the Alessandro Scarlatti Orchestra. Scarlatti wrote several oratorios, and here’s an aria from one of them, Oratorio La Santissima Vergine del Rosario. The music is absolutely exquisite and so is the performance by the incomparable mezzo-soprano Cecilia Bartoli. Les Musiciens du Louvre are conducted by Marc Minkowski.

genius rejuvenates itself in the near future). Alessandro Scarlatti was born on May 2nd of 1660 in Palermo, Sicily (we’ve written about him a number of times, for example here and here). When he was 12, he went to Rome and studied there with Giacomo Carissimi, another seminal figure in the history of Italian opera (Carissimi’s birthday was just several days ago: he was born on April 18th of 1605). Scarlatti wrote his first opera at the age of 19. As so many Roman composers of his time, Scarlatti worked under the patronage of Queen Christina. He then went to Naples to serve at the courts of the Viceroys, who ruled Naples on behalf of the King of Spain. He moved between Naples and Rome for the rest of his life. Scarlatti wrote 115 opera, of which 64 survive. In the process, he came up with a number of innovations, di capo aria being one of them; di capo, a tripartite aria in which the third part repeats the first (di capo meaning “from the head” or from the beginning in Italian), but with improvisations, became a mainstay of the baroque opera. Scarlatti’s last opera, La Griselda, was written in 1721. Here’s the aria In voler cio che tu brami... Che arrechi, Ottone. It’s sung by the wonderful Italian soprano Mirella Freni; Nino Sanzogno conducts the Alessandro Scarlatti Orchestra. Scarlatti wrote several oratorios, and here’s an aria from one of them, Oratorio La Santissima Vergine del Rosario. The music is absolutely exquisite and so is the performance by the incomparable mezzo-soprano Cecilia Bartoli. Les Musiciens du Louvre are conducted by Marc Minkowski.

Ruggero Leoncavallo is famous for just one piece of music, but what a great piece it is! Pagliacci became immensely popular immediately after its first performance in May of 1892 and it remained one of the most often performed operas ever since. Leoncavallo was born on April 23rd of 1857 in Naples into a well-to-do family (his father was a magistrate). Leoncavallo went to the Naples conservatory where he studied composition with an opera composer Lauro Rossi. Upon graduating in 1876, he wrote an opera, Chatterton, but couldn’t get it staged (it was premiered 20 years later but vanished from the repertory soon after). He traveled to Egypt and France and settled in Paris, living a bohemian life and earning some money giving music lessons. In Paris he heard Wagner’s The Ring and decided to create a trilogy as an Italian response to the German epic. He worked on it on and off; the results never amounted to much. In Paris Leoncavallo married Berthe Rambaud, a French singer. Soon after they returned to Milan, where Leoncavallo proceeded to work as librettist and composer; one of his most successful works was the libretto for Giacomo Puccini’s Manon Lescaut. 1890 witnessed the enormously successful premier of Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana. It strongly affected Leoncavallo, who decided to write an opera in a similar realistic (verismo) style and almost immediately started working on Pagliacci (The Clowns). Leoncavallo claimed that he wrote the libretto based on an episode from his childhood, when his father presided over a murder trial involving a love triangle. Some critics maintain that in reality the basis was a French play. The opera was premiered in Milan to mixed critical reviews and great popular acclaim. It became the first complete opera ever to be recorded and the aria Vesti la giubba (Put on the costume) became a signature piece of the great Caruso (his recording of the aria was the first to sell one million copies). Here’s Luciano Pavarotti, in a 1994 recording with the Met orchestra and James Levine.Permalink

April 20, 2015. Sergey Prokofiev. Here at Classical Connect we love all music, from the Renaissance to the contemporary. Of course we cannot get enough of the core, from Bach to the Viennese masters, to the Romantics of the 19th century, and then, through Mahler into the 20th and on. But life would be boring without the great experiments of the early composers, who were trying to find their way from craft to art. Or the more obscure baroque musicians who developed the unheard-of-before styles, such as, for example, opera. And of course we value the music of the late 20th century, as challenging as it sometimes is. And within this enormous aural universe, we have our favorites. Some of them stay with us for a very long time, other retire to the background. The same of course happens with musical tastes in general: just take a look at the Klavierabend (piano recital) programs of the first half of the 20th century: they are drastically different from what you would hear today. One composer that remains our perennial favorite is Sergei Prokofiev. As is the case with so many talented Russian artists whose life spanned two different eras, one before, another after the October Revolution, his life was full of tragedies and triumphs, exiles and returns. We’ve written about Prokofiev, who was born on April 23rd of 1891, many times, for example, here last year, and here the year before. That’s why this time we’ll just play one piano sonata, no. 8. This is the third of the so-called War sonatas; this is a traditional misnomer as the first of the three, Piano Sonata no. 6, was completed in February and premiered in April of 1940, before the Soviet Union was invaded by the Germans. Sviatoslav Richter was the pianist to first play sonatas no. 6 and 7. Sonata no. 8, on the other hand, was premiered by Emil Gilels; the event took place on December 30th of 1944 in the Great Hall of Moscow Conservatory.

Romantics of the 19th century, and then, through Mahler into the 20th and on. But life would be boring without the great experiments of the early composers, who were trying to find their way from craft to art. Or the more obscure baroque musicians who developed the unheard-of-before styles, such as, for example, opera. And of course we value the music of the late 20th century, as challenging as it sometimes is. And within this enormous aural universe, we have our favorites. Some of them stay with us for a very long time, other retire to the background. The same of course happens with musical tastes in general: just take a look at the Klavierabend (piano recital) programs of the first half of the 20th century: they are drastically different from what you would hear today. One composer that remains our perennial favorite is Sergei Prokofiev. As is the case with so many talented Russian artists whose life spanned two different eras, one before, another after the October Revolution, his life was full of tragedies and triumphs, exiles and returns. We’ve written about Prokofiev, who was born on April 23rd of 1891, many times, for example, here last year, and here the year before. That’s why this time we’ll just play one piano sonata, no. 8. This is the third of the so-called War sonatas; this is a traditional misnomer as the first of the three, Piano Sonata no. 6, was completed in February and premiered in April of 1940, before the Soviet Union was invaded by the Germans. Sviatoslav Richter was the pianist to first play sonatas no. 6 and 7. Sonata no. 8, on the other hand, was premiered by Emil Gilels; the event took place on December 30th of 1944 in the Great Hall of Moscow Conservatory.

Prokofiev started writing the sonata much earlier, in 1939. That was the year when he met and fell in love with Mira Mendelson, a young writer half his age. At the time Prokofiev was still married to Lina Llubera (they married in 1923), a Spanish singer whom he met in New York and brought to Moscow in 1936 when he decided to return to the Soviet Union. By 1941 Prokofiev and Lina were separated, and he was living openly with Mira. Mira became Prokofiev’s wife in 1948 and a very troubling story ensued (we’ll write about it another time). Mira is the dedicatee of the Eighth sonata, probably the most complex and deep of the three. Gilels’s 1944 performance was a triumph and soon became an essential part of his vast repertoire. He recoded it a number of times and played it, very successfully, around the world (Richter also made a great recording of the sonata). Here’s a studio recording, made by Gilels in Vienna in 1974. It’s four minutes longer than, for example, his live concert recording of 1967.

Permalink