Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

January 16, 2012

The first two weeks of January. With all the celebrations, religious and secular (two sets of Christmases and New Years, one in the Gregorian calendar, and one in the Julian), we missed several noted birthdays. Mily Balakirev, a Russian composer and the leader of The Five (or The Might Handful – somehow the Russian term escapes a good translation) was born on January 2, 1837. Although not the greatest Russian composer of that time, he still wrote several wonderful pieces, the “Oriental Fantasy” Islamey being probably one of the most popular (and devilishly difficult). Here it is in performance by Sandro Russo. (By the way, one of the members of The Five, Cesar Cui, a Russian composer of French descent – his father entered Russia with Napoleon’s army – was also born around this time, on January 18, 1835).

Giovanni Battista Pergolesi was born on January 4, 1710. His life was tragically short – he died at the age of 26 from tuberculosis, but in the few years that he was actively composing, he wrote a number of opera buffa, some of which are popular to this day, and several sacred works. Probably the best know of them is Stabat Mater, which we’re fortunate to have in the performance by Baroque Band, a period instruments ensemble based in Chicago. You can listen to it here.

Another Russian composer, Alexander Scriabin, was born on January 6, 1872. Scriabin was tremendously popular during his lifetime but fell into relative obscurity in the recent decades. Lately it seems that he has grow in popularity, both on the concert stage and in recordings. Scriabin’s preoccupation with color (he even created a color keyboard, with each key associated with a specific hue) is well known. Recently Eteri Andjaparidze performed a full program of Scriabin in the Baryshnikov center, accompanied by Jennifer Tipton’s intricate, colorful lighting design to create an unusual experience of sound and sight. In the absence of color we will hear Beatrice Berrut play Scriabin’s Piano Sonata no. 3 in f-sharp minor op.23 (click here).

And finally the French composer Francis Poulenc was born on January 7, 1899. Poulenc, a member of The Six, wrote music for piano (solo and a concerto), wonderful chamber music, especially for wind instruments, liturgical music and operas, but he’s probably best known for his songs. In this field his lyrical talent was incomparable. Here’s the song with an unusual title Mon cadavre est doux comme un gant (My dead body is soft as a glove). It comes from Poulenc’s cycle Fiançailles pour rire, based on the poems of Louise de Vilmorin. It’s sung by the baritone Michael Kelly (Jonathan Ware is on the piano).

January 9, 2012

Born in Taiwan, the pianist Stephanie Shih-yu Cheng was about 5 when she started lessons, and started competing when she was 7. She moved to the US when she was 16 to study music at Michigan's Interlochen Academy. Ms. Cheng’s principal teachers have been Ann Schein at the Peabody Conservatory and Gilbert Kalish. She also earned a Doctor of Musical Arts degree from State University of New York at Stony Brook.

Ms. Cheng has performed in the U.S., France, Italy, Japan, and Taiwan to great critical acclaim. She played at the world’s major music centers, including the Weill Recital Hall at Carnegie Hall in New York, Dame Myra Hess Concert Series in Chicago, Opera City Hall of Tokyo, National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., Kravis Center in Florida, and the National Concert Hall of Taipei. She has distinguished herself in several international competitions, including first prizes in the IBLA Grand Prize Competition in Italy, Kingsville International Competition, and the Association of Pianists and Piano Teachers of America International Piano Competition. She was the recipient of Prix-Ville de Fontainebleau in France, which was presented to her by Philippe Entremont. Martin Bernheimer wrote that she plays “eloquently and elegantly…(with) passion and introspection…sensitivity and a finely honed sense of style.” Her recent engagements include concerts with the Stony Brook Symphony under Leon Fleisher and Brampton Symphony Orchestra in Toronto. She frequently appears in recitals with pianist Sara Davis Buechner.

Ms. Cheng was a teaching assistant for Earl Carlyss at the Peabody Conservatory where she received the Rose Marie Milholland Award in Piano. Currently she is on the faculties of the Manhattan School of Music Precollege and City College of New York

Ms. Cheng’s repertoire is broad, but we’ll hear Stephanie play several French Impressionist pieces. First, Scarbo from Maurice Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit (here). We’ll follow with Claude Debussy’s Soiree dans Grenade, from Estampes (here). Finally, back to Ravel and his Sonatine (here). You can find more of Ms. Chang’s performances on her personal page.

January 2, 2012. Happy 2012! Thanks to the tradition of the Vienna Philharmonic concerts, New Year’s music tends toward Johann Strauss Jr. and the 19th century operetta. As much as we enjoy Vienna, this is not the kind of music we love. So we turn again to Bach’s magnificent Christmas Oratorio: Part IV was written for the Feast of the Circumcision of Christ, which falls on New Year's day, and Part V – for the first Sunday of the New Year. Here is the opening chorus from Part IV, Fallt mit Danken, fallt mit Loben (Fall Down in Thanks, Fall Down in Praise). And here is the first movement (Chorus) Ehre sei dir, Gott, gesungen (Let your glory be sung out, oh God) from Part V. Both are performed by English Baroque Soloists the Monteverdi Choir under the direction of John Eliot Gardiner (courtesy of YouTube).

Pictured on the left is St. Nicholas church in Leipzig. It’s interesting that during Bach’s time the only complete performance of the Oratorio took place in St. Nicholas (it happened between December 25, 1734 and January 6, 1735). Only four parts were performed in Bach’s own church of St. Thomas. Two and a half centuries later, in 1989, St. Nicholas became the center of demonstrations against East Germany’s Communist regime, which in the end brought down Berlin Wall.

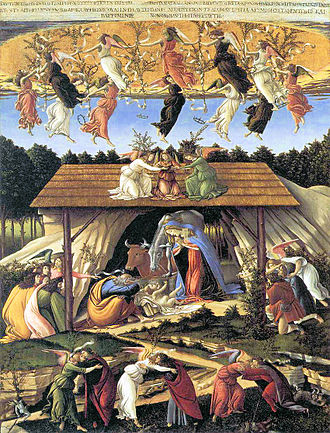

PermalinkDecember 26, 2011. Happy Holidays to all!

Merry Christmas, Happy Hanukkah, which this year almost coincided with Christmas, and Happy New Year to all musicians, and classical music lovers! Have a wonderful holiday season, and here to celebrate we have two pieces of great music.

Have a wonderful holiday season, and here to celebrate we have two pieces of great music.

First, from Johann Sebastian Bach’s Christmas Oratorio, aria Schlafe, mein Liebster (Sleep now, my dearest). It’s especially appropriate because it comes from the part that was written for the second day of Christmas, December 26. Schlafe, mein Liebster is performed by the English Baroque Soloists, the Monteverdi Choir under the baton of John Eliot Gardiner. Bernarda Fink is the mezzo-soprano. To listen, click here.

We couldn’t find any appropriate classical music to celebrate Hanukkah. In the 3rd movement of his First Symphony, Mahler uses a Jewish folk tune, which he even orchestrated to sound like a klezmer band (it comes after the famous Frère Jacques quote). This is as close as we could come. The complete 3rd movement is here. Lorin Maazel conducts the Wiener Philharmoniker. Both musical excerpts are courtesy of YouTube.

PermalinkDecember 19, 2011

Two more of Beethoven’s late Quartets. A couple weeks ago, as Beethoven’s birthday was approaching, we featured two of Beethoven’s late quartets, op. 132 and op. 131. Today we’ll introduce two more, op. 130 and op. 135.

As with all late quartets, there’s confusion regarding their numbers. String Quartet no. 13 in B-flat major op. 130, though second in order of publication, was actually composed during 1825-6 after the quartet in a minor, op. 132, making it the last of the quartets composed to fulfill the commission from the Russian prince Nikolai Galitzin. Whereas the quartet in a minor was Beethoven’s reflection on his recovery from a life-threatening illness, which gave birth to the profound and solemn "Heiliger Dankgesang" (Song of Thanksgiving) that forms the quartet’s centerpiece, the Quartet in B-flat major is quite possibly then the expression of renewed vigor and the composer’s exuberant return to his art. Hardly anywhere in the piece is there a mournful or sad measure. Premiered in March 1826, the original form of the Quartet in B-flat major included the colossal Grosse Fuge as the finale. Opinions of the performance were mixed mostly because of the fugue, which nearly eclipsed, artistically and temporally, the rest of the quartet. Urged by his publisher to replace the fugue with a less weighty finale, Beethoven composed an alternate ending in the fall of 1826, making this a rare instance in which Beethoven was swayed by either the opinion of the public or the publisher. Furthermore, the alternate finale was also his last completed composition. We’ll hear the quartet in its original form. It’s performed by Angelo Xiang Yu, violin, Miriam Fried, violin, Philip Kramp, viola, and Deborah Pae, cello. You can listen to it here.

Beethoven composed his sixteenth String Quartet, Op.135 in F Major, in 1826, a mere few months before his death. Only one other completed composition, the alternate finale for the op. 130 quartet in B-flat major, postdates this work. In this sense, the string quartet in F major represents the culmination of a lifelong dedication to music. Of the late string quartets, the F major is the shortest (26 and a half minutes in this recording), the simplest in construction, and the only other quartet to follow the standard four movement plan besides the op. 127 quartet in E flat major. While in technique the F major quartet no doubt deserves its place among the other late quartets, it does not seem to burden itself with the same weighted discourse. Instead, as the French musicologist Joseph de Marliave stated, it is a "fluent play of brilliant but irresponsible wit," much like the alternate finale Beethoven composed for the op. 130 quartet. The final movement, titled Der schwer gefaβte Entschluβ ("The Difficult Decision"), is perhaps the most famous part of the quartet, largely due to the purportedly philosophical question Beethoven penned above the slow introductory chord: "Es muss sein?" (Must it be?). The answer that Beethoven gives later in the manuscript is simply, "Muss es sein" (It must be). Because of the obvious ambiguity of this question-answer pair, many solutions to this enigma have been proposed, each trying to tease out a meaning that may or may not be there. One of the more well-known explanations, and at least the most comical, comes from Anton Schindler. Schindler states that Beethoven's housekeeper, the only person allowed to disturb him while he was working, would ask him for money with which to buy food and other necessities. Beethoven would reply, "Es muss sein?" (Must it be?). The housekeeper would then emphatically reply, "Muss es sein" (It must be). Here is the performance of quartet op. 135 by Avalon String Quartet.

December 12, 2011

Beethoven. The great German composer was born on the 15th or 16th of December, 1770 (all we know for sure is that he was baptized on the 17th). There’s no need to recount his life: hundreds of books of books were written about him, and his life, from his birth in Bonn, to his studies with Haydn in Vienna, to his first works, still influenced by Mozart and Haydn, to the onset of his hearing loss, to his mature period and then the burst of immense creativity at the late period, when he was completely deaf – al of this is part of the cultural lore. Instead, we’ll just present several pieces from the different periods of his life.

Piano Trio, Op. 11 is an early piece. It was originally written in 1797 as a trio for clarinet, piano and cello, which he then transcribed the for the violin, cello and piano. The trio has the nickname "Gassenhauer" or "Street Song" Trio because of the theme in the last movement, which derives from a popular song of the day. Beethoven used it as a theme for nine variations. It is performed by Lincoln Trio and can be heard here.

String Quartet No. 6 in B-flat Major op. 18, no.6 was written two-three years later, around 1800. Beethoven published his first six quartets as a single opus, just as Haydn and Mozart, who also had published their own multi-quartet sets. The first movement is still quite Haydnesq, but it’s the finale, subtitled La Malinconia" (Melancholy), that is surprisingly innovative. The opening is full of unexpected harmonies and dynamic shifts, and in this sense it portends of the later quartets. It’s performed by Arianna String Quartet, and you listen to it here.

Sonata for violin and piano No. 8 in G Major, the third in opus 30 sonatas, was written in 1801 or 1802. It’s dedicated to the Russian czar Alexander I, somewhat surprising, considering Beethoven’s Republican inclinations.It’s played here by Christoph Seybold, violin and Milana Chernyavska, piano. With its solid sonata form, this wonderful piece is still characteristic of early Beethoven.

From 1804, the beginning of Beethoven's "Heroic" decade (1803-1812), comes one his greatest pianos sonatas of the period, Piano Sonata No. 21 in C major "Waldstein." The Waldstein surpasses Beethoven's previous sonatas in both depth, scope, and freedom of form, setting the stage for his later piano sonatas. The sonata got its name from the dedicatee, Count Waldstein. In Italy and Russia the sonata is known as 'L'Aurora' (the dawn in Italian), probably for the serenity of the opening chords of the third movement. The Waldstein is performed by the pianist Yukiko Sekino. Listen to it here.

We’ll jump almost 17 years, to one of Beethoven’s last sonatas, Sonata in A Flat Major, Op. 110. Between 1810 and 1819 Beethoven wrote just two piano sonatas, but in the years 1819 through 1822 he wrote and published one sonata a year, from the magisterial no. 29, op. 109 “Hammerklavier” to op. 111, the two-part sonata no. 32. Sonata no. 31 is in three movements; the profound third movements consists of several sections, two of which represent a fugue and another one, its inversion. The sonata is played here by the pianist Inesa Sinkevych.

And finally, Große Fuge (Grande Fugue), from 1826. Große Fuge was composed as the final movement of his Quartet No. 13 in B-flat Major, Op. 130. Later Beethoven replaced the finale of the quarter and published the Fugue separately, as opus 133. The contemporaries described the fugue as “incomprehensible” and “a confusion of Babel.” This contrapuntal tour de force is still very demanding on both performers and listeners. Here is it performed by the violinists Angelo Xiang Yu and Miriam Fried, Philip Kramp, viola, and Deborah Pae, cello.