Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

June 25, 2012. On Italian Baroque. Recently, while contemplating some pictures of Rome, we were struck, yet again, by the incongruity of terms we use to describe art. This, of course, is part of a much larger problem, one with which this site struggles often when attempting to "describe" music and performances. The way we try to deal with this issue here is by avoiding it whenever possible: we let our users listen to the music instead of talking about it. Still, the problem remains and manifests itself not only when we attempt the impossible, as in "describing" music, but even in much more mundane areas, such as when we try to classify historical art periods. The term "Baroque" is case in point. The Baroque architecture of Rome has its origins in the late 16th – early 17th century (Carlo Maderno designed Santa Susanna around 1603), and reached its glorious zenith with the works of Francesco Borromini, Pietro Cortona and Gian Lorenzo Bernini in the mid-1600s. When we think "Rome" – the façade of Saint Peter’s, the two iconic churches off Piazza Venezia, Santa Maria di Loreto and Santissimo Nome di Maria al Foro Traiano, the interior of the Gesù, the Trevi fountain – all of it is Baroque. But the music that played in Santa Susanna was not "Baroque" in our understanding of the term. Most likely it was written by composers of the Roman school, like Palestrina and the Spaniard, Tomás Luis de Victoria. Another Roman, Gregorio Allegri, composed his famous Miserere in the1630s (it would not have been sung at Santa Susanna anyway, as it was composed specifically for use in the Sistine Chapel). And as much as we like Palestrina and Victoria, it’s clear that music as art did notdevelop to the heights it had reached in its visual forms till much later, and it didn’t happen in Rome. Lully, and later Rameau and Couperin in France, Purcell in England, and later still Vivaldi, Scarlatti, Bach and Handel brought it to the canonical level which we habitually allot to the great painter and architects of Italy.

course, is part of a much larger problem, one with which this site struggles often when attempting to "describe" music and performances. The way we try to deal with this issue here is by avoiding it whenever possible: we let our users listen to the music instead of talking about it. Still, the problem remains and manifests itself not only when we attempt the impossible, as in "describing" music, but even in much more mundane areas, such as when we try to classify historical art periods. The term "Baroque" is case in point. The Baroque architecture of Rome has its origins in the late 16th – early 17th century (Carlo Maderno designed Santa Susanna around 1603), and reached its glorious zenith with the works of Francesco Borromini, Pietro Cortona and Gian Lorenzo Bernini in the mid-1600s. When we think "Rome" – the façade of Saint Peter’s, the two iconic churches off Piazza Venezia, Santa Maria di Loreto and Santissimo Nome di Maria al Foro Traiano, the interior of the Gesù, the Trevi fountain – all of it is Baroque. But the music that played in Santa Susanna was not "Baroque" in our understanding of the term. Most likely it was written by composers of the Roman school, like Palestrina and the Spaniard, Tomás Luis de Victoria. Another Roman, Gregorio Allegri, composed his famous Miserere in the1630s (it would not have been sung at Santa Susanna anyway, as it was composed specifically for use in the Sistine Chapel). And as much as we like Palestrina and Victoria, it’s clear that music as art did notdevelop to the heights it had reached in its visual forms till much later, and it didn’t happen in Rome. Lully, and later Rameau and Couperin in France, Purcell in England, and later still Vivaldi, Scarlatti, Bach and Handel brought it to the canonical level which we habitually allot to the great painter and architects of Italy.

The church in the picture above is Sant'Andrea della Valle, on what is now Corso Vittorio Emanuele II in Rome. It was designed mainly by Carlo Maderno in 1608 and completed later. Here is an example of the music that could be heard in this church during that time. It’s a motet by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, Sicut cervus desiderat, (“As the deer thirsts for the waters, so my soul longs for Thee, O God”). It’s performed by the Westminster Cathedral Choir (courtesy of YouTube).

PermalinkJune 24, 2012. Today is the birthday of a dear friend of Classical Connect, Lev Solomonovich Ruzer: he turns 90! A physicist by profession who successfully transitioned from running a research lab in the Soviet Union to the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, he’s also an amateur pianist. He started piano lessons in his teens,continued playing while at Moscow University, and he still plays piano every day! We suspect that music is what supports his amazing vitality and joie de vivre. On this wonderful day we join his family in wishing him great health, lots of love and more music to enjoy.

A physicist by profession who successfully transitioned from running a research lab in the Soviet Union to the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, he’s also an amateur pianist. He started piano lessons in his teens,continued playing while at Moscow University, and he still plays piano every day! We suspect that music is what supports his amazing vitality and joie de vivre. On this wonderful day we join his family in wishing him great health, lots of love and more music to enjoy.

We could probably record a Classical Connect rendition of Happy Birthday, but we suspect Lev Solomonovich would not be impressed. Here, instead, is the Venezuelan-American pianist Gabriela Montero playing her own improvisation on the traditional tune. She does a much better job with it.

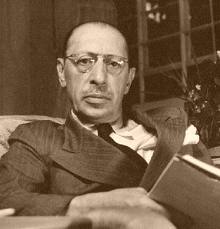

PermalinkJune 18, 2012. Igor Stravinsky. We didn’t have time to talk about Stravinsky last week, but he’s too big a presence in classical music to leave him out completely, so we’ll do it this week instead. Stravinsky was born on June 17, 1882 in Oranienbaum, as small town just outside of Saint Petersburg, famous for one the imperial palaces located there. In the past, we’ve written about Stravinsky quite a bit, both about his peregrinations and the radical changes in his compositional style. There’s no doubt that Stravinsky was a musical giant. His compositions, from the early “Russian” ballets The Firebird and The Rite of Spring, to neoclassical composition, such as ballets Pulcinella and Apollon musagète, two symphonies, in C and in Three Movements, and the opera The Rake's Progress, to the latest forays in serialism – practically his complete oeuvre belongs in the pantheon of classical music of the 20th century. But what we thought we’d mention this time, especially in juxtaposition to Richard Strauss, whom we wrote about last week, is the very trite but still somehow surprising fact that geniuses are not always necessarily good. And we don’t mean being “good” in everyday life, although Stravinsky was, apparently, even though entertaining, a rather unpleasant person to be around. We mean their beliefs and political views. It’s well known that Stravinsky was anti-Semitic. That’s not very surprising, considering his aristocratic background and the fact that the Russian aristocracy during the last years of the monarchy was to a large degree anti-Semitic, with wonderful exceptions, of course, such as the Nabokov family. What comes as a shock is Stravinsky’s infatuation with Mussolini. In an interview he gave to the music critic of Rome’s La Tribuna in 1930 he said: “I don't believe that anyone venerates Mussolini more than I… I have an overpowering urge to render homage to your Duce. He is the savior of Italy and – let us hope – Europe.” He also wrote to a German publisher in 1933, “I am surprised to have received no proposals from Germany for next season, since my negative attitude toward communism and Judaism – not to put it in stronger terms – is a matter of common knowledge.” It’s quite ironic that Nazi cultural censors declared Stravinsky a “Jewish modernist” and banned his work from Germany.

just outside of Saint Petersburg, famous for one the imperial palaces located there. In the past, we’ve written about Stravinsky quite a bit, both about his peregrinations and the radical changes in his compositional style. There’s no doubt that Stravinsky was a musical giant. His compositions, from the early “Russian” ballets The Firebird and The Rite of Spring, to neoclassical composition, such as ballets Pulcinella and Apollon musagète, two symphonies, in C and in Three Movements, and the opera The Rake's Progress, to the latest forays in serialism – practically his complete oeuvre belongs in the pantheon of classical music of the 20th century. But what we thought we’d mention this time, especially in juxtaposition to Richard Strauss, whom we wrote about last week, is the very trite but still somehow surprising fact that geniuses are not always necessarily good. And we don’t mean being “good” in everyday life, although Stravinsky was, apparently, even though entertaining, a rather unpleasant person to be around. We mean their beliefs and political views. It’s well known that Stravinsky was anti-Semitic. That’s not very surprising, considering his aristocratic background and the fact that the Russian aristocracy during the last years of the monarchy was to a large degree anti-Semitic, with wonderful exceptions, of course, such as the Nabokov family. What comes as a shock is Stravinsky’s infatuation with Mussolini. In an interview he gave to the music critic of Rome’s La Tribuna in 1930 he said: “I don't believe that anyone venerates Mussolini more than I… I have an overpowering urge to render homage to your Duce. He is the savior of Italy and – let us hope – Europe.” He also wrote to a German publisher in 1933, “I am surprised to have received no proposals from Germany for next season, since my negative attitude toward communism and Judaism – not to put it in stronger terms – is a matter of common knowledge.” It’s quite ironic that Nazi cultural censors declared Stravinsky a “Jewish modernist” and banned his work from Germany.

We probably could go on, but our site is about music, not politics. Here is a wonderful piano arrangement by Guido Agosti of an excerpt from the Firebird Suite. It’s performed by the pianist Daniil Trifonov.

PermalinkJune 11, 2012. A bountiful week. Richard Strauss, Edvard Grieg, Charles Gounod, and Igor Stravinsky were all born this week. Richard Strauss was born on June 11, 1864. He clearly deserves our full attention, but this week, so full packed with birthdays, we’d like to make just two comments. One is on his place in the musical Pantheon of the late 19th – early 20th century. Strauss said, with amazing self-deprecation, "I may not be a first-rate composer, but I am a first-class second-rate composer." We’d like to disagree. The place of the composer is judged by his best output, not some abstract “average” weighted down by weaker pieces (think of the number of mediocre music written, for example, by Tchaikovsky). Strauss’ tone poems, such as Also sprach Zarathustra, Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks, An Alpine Symphony are all first-rate. As are his operas, Der Rosenkavalier, Ariadne auf Naxos, Salome, and other. And so is his Violin sonata, op. 18 (you can listen to it here, performed by Ilya Kaler, violin, and Eteri Andjaparidze, piano. He also wrote wonderful songs (here is Cäcilie, Op. 27, No. 2, sung by the soprano Janai Brugger-Orman, with Renate Rohlfing on the piano). He clearly was a great composer. And the other comment is to Strauss’ decency. Totally apolitical, he maintained relations with Jewish writers and artists when it was already considered inopportune in Nazi Germany. Here’s a great quote from his letter to the writer Stefan Zweig: “Do you believe I am ever, in any of my actions, guided by the thought that I am 'German'? Do you suppose Mozart was consciously 'Aryan' when he composed? I recognize only two types of people: those who have talent and those who have none.”

birthdays, we’d like to make just two comments. One is on his place in the musical Pantheon of the late 19th – early 20th century. Strauss said, with amazing self-deprecation, "I may not be a first-rate composer, but I am a first-class second-rate composer." We’d like to disagree. The place of the composer is judged by his best output, not some abstract “average” weighted down by weaker pieces (think of the number of mediocre music written, for example, by Tchaikovsky). Strauss’ tone poems, such as Also sprach Zarathustra, Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks, An Alpine Symphony are all first-rate. As are his operas, Der Rosenkavalier, Ariadne auf Naxos, Salome, and other. And so is his Violin sonata, op. 18 (you can listen to it here, performed by Ilya Kaler, violin, and Eteri Andjaparidze, piano. He also wrote wonderful songs (here is Cäcilie, Op. 27, No. 2, sung by the soprano Janai Brugger-Orman, with Renate Rohlfing on the piano). He clearly was a great composer. And the other comment is to Strauss’ decency. Totally apolitical, he maintained relations with Jewish writers and artists when it was already considered inopportune in Nazi Germany. Here’s a great quote from his letter to the writer Stefan Zweig: “Do you believe I am ever, in any of my actions, guided by the thought that I am 'German'? Do you suppose Mozart was consciously 'Aryan' when he composed? I recognize only two types of people: those who have talent and those who have none.”

If we ever had some doubts about the accepted "rankings" of great composers, Edvard Grieg’s position would’ve been the one to question. But the overwhelming popularity of his Piano Concerto and incidental music to Peer Gynt clearly outweigh any snobbish pretenses. He also deserves additional points for being the only national composer in the modern history of Norway! But before our listeners start sending us indignant messages, here is In the Hall of the Mountain King, from the Peer Gynt suite, played by McKeever Piano Duo. And here is Grieg’s wonderful Violin Sonata, op. 45. It’s performed by Gregory Maytan, violin and Nicole Lee, piano. And why are we writing about Grieg? He was born this week, on June 15, 1843 in the city of Bergen in what was then the Union of Sweden and Norway. The Union was dissolved in 1905, two years before Grieg’s death, so there are no questions about Grieg’s nationality!

Just one song from Charles Gounod, the oldest in this group: he was born on June 17, 1818. The young mezzo-soprano Rebecca Henry sings Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle?, Tom Jaber is on the piano (here). We’ll write about Igor Stravinksy (June 17, 1882 – April 6, 1971), who clearly was one of the greatest composers of the 20th century (but probably not as nice a person as Richard Strauss) some other time.

PermalinkJune 4, 2012. Beatrice Berrut. One of the first pieces that Ms. Berrut uploaded to Classical Connect was Schumann’s Piano Sonata no. 1. Schumann was just 23 when he composed what he called Grosse Sonate ("Grand Sonata"). Schumann had at the time already written a number of great pieces, from Papillons to Toccata in C Major to Carnaval, but clearly he still wanted to write a serious, classical piece (perhaps to impress his bride, the young virtuoso Clara Wieck). Beatrice was the same age of 23 when she recorded the sonata in 2009. What impresses the listener in this recording is the depth, the seriousness of it, something you may not expect from a young performer. This is the hallmark of Ms. Berrut’s art. Whether she plays her beloved Schumann (she recorded all three piano sonatas for Centaur Records), Chopin, Brahms, or Scriabin, she digs deep into the music to uncover the essence and bring it to the listener. The great violinist Gidon Kremer recognized this quality when he described Beatrice as “a wonderfully talented and musical pianist, with impressive seriousness, commitment and sensitivity.”

number of great pieces, from Papillons to Toccata in C Major to Carnaval, but clearly he still wanted to write a serious, classical piece (perhaps to impress his bride, the young virtuoso Clara Wieck). Beatrice was the same age of 23 when she recorded the sonata in 2009. What impresses the listener in this recording is the depth, the seriousness of it, something you may not expect from a young performer. This is the hallmark of Ms. Berrut’s art. Whether she plays her beloved Schumann (she recorded all three piano sonatas for Centaur Records), Chopin, Brahms, or Scriabin, she digs deep into the music to uncover the essence and bring it to the listener. The great violinist Gidon Kremer recognized this quality when he described Beatrice as “a wonderfully talented and musical pianist, with impressive seriousness, commitment and sensitivity.”

Beatrice was born in the Swiss canton of Valais, and started the piano rather late, at the age of 9, first in Lausanne with Pierre Goy (paino) and Pierre Amoyal (chamber music), and then at the Neuhaus Foundation in Zurich under renowned pianist Esther Yellin, a pupil of Henrich Neuhaus. She then graduated from the Hanns Eisler Hochschule für Musik in Berlin, where she studied with Galina Iwanzowa. She receives regular guidance from Menahem Pressler and John O’Conor. Beatrice says that she’s also influenced by her work with pianists Brigitte Engerer and Leon Fleisher.

The winner of the Société des Arts Competition in Geneva, she was the Swiss laureate at the Eurovision Contest for young classical musicians, and represented Switzerland at the European Contest in Berlin. She also won the Bach special award at Wiesbaden International Piano Competition. Since the release of her debut CD in 2003 featuring works by Beethoven, Schumann, and Liszt, Beatrice has been in demand as a soloist both in recitals and with numerous orchestras, such as the Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana, Kammerphilharmonie Berlin, Menuhin Chamber Orchestra. She also appears regularly on Swiss, German, US, and Canadian radio and television.

A keen chamber musician, Beatrice was invited in 2005 by Gidon Kremer to play several concerts at his festival in Basel, and in 2007 and 2008 by Shlomo Mintz to his festival in Sion as well as \duo recitals in Argentina in September 2011. In August 2011, she performed Schumann’s Quintet with Itzhak Perlman at the Hamptons, NY.

On Wednesday, June 6 Beatrice will perform at the Dame Myre Hess concert in Chicago. On the program are two Bach chorales in Busoni’s transcription, Chaconne in d minor, and Liszt’s Après une Lecture de Dante. If you cannot make it to the concert, you can listen to Après une Lecture here.

PermalinkMay 28, 2012. Isaac Albéniz. When Isaac Albéniz was born on May 29, 1860, Spanish classical music was in a long decline. Spain was the country where music flourished during the Renaissance and Baroque periods. In the early 16th century Spanish composers were in the forefront of the polyphonic development. Local musicians traveled to Burgundy, France and the Flemish cities, studied and made music with the best of them; many of the best composers went to the courts of Spanish kings. The music of Cristóbal de Morales (1500 – 1553) was known in many European countries. Tomás Luis de Victoria (1548 –1611) is considered one of the greatest composers of the late Renaissance, on par with Giovanni da Palestrina and Orlando di Lasso. During the Baroque period, music continued to thrive. Gaspar Sanz (1640 – 1710) was one of the most important composers for the guitar. Domenico Scarlatti spent a large part of his productive life in Spain. Padre Antonio Soler (1729 –1783) followed in his steps; Soler’s keyboard sonatas are part of the regular piano repertory and are played often. Luigi Boccherini, like Scarlatti, was born in Italy but spent most of his life in Madrid. By the 1800s, however, classical music waned, as did much of the Spanish culture in general. Albéniz was the oldest of the first group of talented composer (together with Enrique Granados, Manuel de Falla and Joaquín Turina) to revive Spanish music in the late 19th century and bring it into the 20th.

Spain was the country where music flourished during the Renaissance and Baroque periods. In the early 16th century Spanish composers were in the forefront of the polyphonic development. Local musicians traveled to Burgundy, France and the Flemish cities, studied and made music with the best of them; many of the best composers went to the courts of Spanish kings. The music of Cristóbal de Morales (1500 – 1553) was known in many European countries. Tomás Luis de Victoria (1548 –1611) is considered one of the greatest composers of the late Renaissance, on par with Giovanni da Palestrina and Orlando di Lasso. During the Baroque period, music continued to thrive. Gaspar Sanz (1640 – 1710) was one of the most important composers for the guitar. Domenico Scarlatti spent a large part of his productive life in Spain. Padre Antonio Soler (1729 –1783) followed in his steps; Soler’s keyboard sonatas are part of the regular piano repertory and are played often. Luigi Boccherini, like Scarlatti, was born in Italy but spent most of his life in Madrid. By the 1800s, however, classical music waned, as did much of the Spanish culture in general. Albéniz was the oldest of the first group of talented composer (together with Enrique Granados, Manuel de Falla and Joaquín Turina) to revive Spanish music in the late 19th century and bring it into the 20th.

We’ll hear three piano pieces by Albéniz. First, Jorge Federico Osorio plays Granada, from Suite Española no. 1 (here). Then the young American pianist Pia Bose performs El Albaicín, from one of the most important Albéniz’s compositions, the suite Iberia (El Albaicín comes from Book III), here. And finally (here), the Russian-American pianist Dmitry Paperno plays Cordoba, Op. 232, No. 4. Here’s what Paperno writes about Cordoba: "The slow introduction to this beautiful piece describes the stillness of a Spanish night. One moment in particular strikes me because it comes extremely close to the sound of Russian Orthodox choir music. This is apparently coincidental, although there are definitely some links between Spanish and Russian music (starting with two Spanish Overtures by Glinka). The faster part of Cordoba is like a melancholic serenade accompanied by guitar. Its victorious major key culmination is interrupted at its peak. The piece never gets all that fast, however, because Spanish music always contains a feeling of dignity and melancholy." We’ll use this quote to segue into yet another anniversary, that of the above-mentioned Mikhail Glinka. Glinka, who was born on June 1, 1804, was, like Albéniz, a pioneer: there was practically no original classical music before his time. Here is Glinka’s piano piece, The Lark, it is performed by the American pianist Tanya Gabrielian.

Permalink