Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

September 17, 2012. We have some unfinished business from the two previous weeks. With the explosion of anniversaries we had very little time to write about Arnold Schoenberg and Antonin Dvořák. With Schoenberg we traced his career to the point when he abandoned tonality in pieces such as Pierrot Lunaire, Op. 21, written in 1912. Though very radical in its completeness, Schoenberg’s atonal music was not truly revolutionary: even Wagner extensively used shifting tonalities in his operas, sometimes to such extent that the major tonal center would seem to completely disappear (many of you may have heard it last week on public television during the rebroadcast of the wonderful Ring Cycle from the Metropolitan Opera). Some works of Debussy had the same quality, but of course not to the degree as used by Schoenberg. As unusual as it sounds, the atonal music still maintains the traditional tonal relationships, except that they are dispersed in small droplets within the composition. Schoenberg didn't stop there: he evolved his style to eliminate all traces of tonality, making all 12 tones of the scale equal throughout a piece of music. This style became known as dodecaphone, or the twelve tone technique. Schoenberg "invented" it around 1921. By then he had already established a group of followers and pupils who became known as the Second Viennese School. The key participants in this group were the tremendously talented Alban Berg and Anton Webern. Among other noted members were Hanns Eisler and Viktor Ullmann. All of them continued composing in the twelve tone style, which became extremely influential by the middle of the century. Composers such as Milton Babbitt in the US, the Frenchman Pierre Boulez, the Italians Luciano Berio and Luigi Dallapiccola, and the Austrian-American Ernst Krenek were major proponents of the system. Even Stravinsky experimented with it.

traced his career to the point when he abandoned tonality in pieces such as Pierrot Lunaire, Op. 21, written in 1912. Though very radical in its completeness, Schoenberg’s atonal music was not truly revolutionary: even Wagner extensively used shifting tonalities in his operas, sometimes to such extent that the major tonal center would seem to completely disappear (many of you may have heard it last week on public television during the rebroadcast of the wonderful Ring Cycle from the Metropolitan Opera). Some works of Debussy had the same quality, but of course not to the degree as used by Schoenberg. As unusual as it sounds, the atonal music still maintains the traditional tonal relationships, except that they are dispersed in small droplets within the composition. Schoenberg didn't stop there: he evolved his style to eliminate all traces of tonality, making all 12 tones of the scale equal throughout a piece of music. This style became known as dodecaphone, or the twelve tone technique. Schoenberg "invented" it around 1921. By then he had already established a group of followers and pupils who became known as the Second Viennese School. The key participants in this group were the tremendously talented Alban Berg and Anton Webern. Among other noted members were Hanns Eisler and Viktor Ullmann. All of them continued composing in the twelve tone style, which became extremely influential by the middle of the century. Composers such as Milton Babbitt in the US, the Frenchman Pierre Boulez, the Italians Luciano Berio and Luigi Dallapiccola, and the Austrian-American Ernst Krenek were major proponents of the system. Even Stravinsky experimented with it.

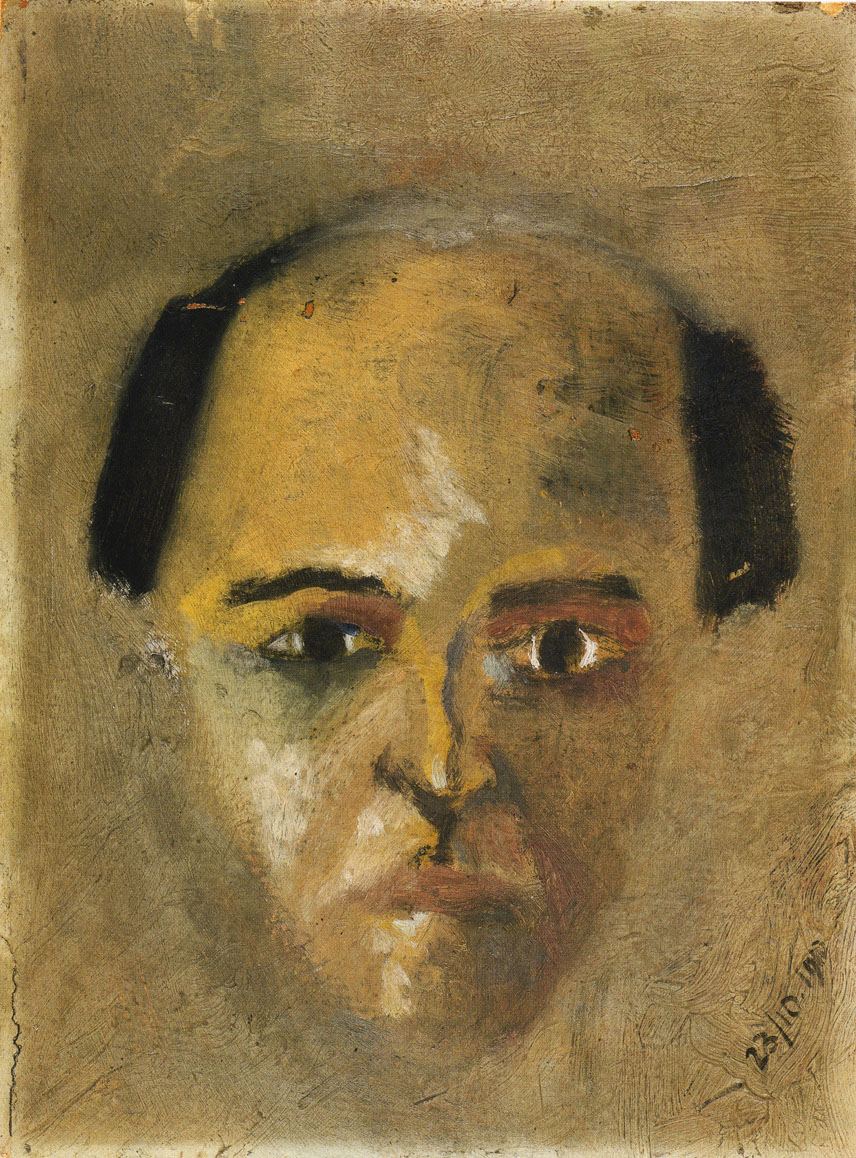

In 1924 Schoenberg moved to Berlin, accepting the position of Director of the Master Class in Composition at the Prussian Academy of Arts. He held this position till 1933, when Adolf Hitler was elected Chancellor of Germany. Fearing for his safety, Schoenberg moved to the United States and eventually settled in Los Angeles. He taught at UCLA and the University of Southern California (John Cage and Lou Harrison were among his students). He also continued composing; among the music written during this period are two concertos, one for the violin and another for the piano, and (the unfinished) opera Moses und Aron. We'll hear the first movement of the Piano concerto, performed by Mitsuko Uchida and the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, Jeffrey Tate conducting (here, courtesy of YouTube). Schoenberg was also a serious amateur painter. The picture above is a self-portrait, painted in 1910.

It's hard to imagine a composer more different than Schoenberg, but here we are, celebrating Antonin Dvořák. His anniversary was two weeks ago, but at that time we were too busy with Bruckner. It's interesting that on a superficial but factual level, one can find a lot of similarities between Schoenberg and Dvořák. A generation apart (Dvořák was born in 1841, Schoenberg in 1874) both were children of the Austrian Empire: Dvořák was born near Prague, the capital of Bohemia (now the Czech Republic), which back then was an important part of the empire, Schoenberg in Vienna. Both spent some time in the US: Schoenberg, the last 18 years of his life, Dvořák - three very productive years at the end of his. Musically, both were influenced by Brahms, which, while unnoticeable in Schoenberg's later compositions, is very clear in all of Dvořák's oeuvre. And during different periods of their respective careers, both were supported by Gustav Mahler. But as far as their compositions are concerned, while Schoenberg was a revolutionary, Dvořák was everything but. Which of course doesn't mean that he didn't write some wonderful music: his "New World" symphony, the cello concerto, the opera "Rusalka," some songs, quartets, and piano music are first class. Here is his Piano Quintet in A major, Op. 81. It's performed by Tessa Lark and Yoon-Jung Yang, violins, Yiyin Li, viola, Sébastien Gingras, cello and Helen Huang, piano.Permalink

This week is almost as rich with birthdays. William Boyce, one of the most important English composers of the 18th century was born around September 11, 1711 (he was baptized that day). Friedrich Kuhlau, a Danish composer, was born on September 11, 1786. These days he may not be performed very often in concert halls, but anybody who ever studied piano has most likely played one of his pieces. September 11th is also the birthday of the one of most interesting living composer, the Estonian Arvo Pärt. He was born in 1935. We’ll definitely write more about him at a later time. Clara Schumann, the wife of Robert Schumann, a pianist and composer and close friend of Johannes Brahms, was born on September 13, 1819. But the person we’d like to commemorate today at least to some degree is Arnold Schoenberg. He was born in Vienna on September 13, 1874 into a middle-class Jewish family. The only musical lessons he ever took were from the composer Alexander von Zemlinsky, his future brother-in-law. Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss were early supporters of Schoenberg, even though initially Schoenberg didn’t like Mahler’s music (he was "converted" after hearing Mahler’s Third Symphony). His first significant work was the string sextet Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night), written in 1899. Clearly a late-Romantic piece, it’s still a tonal composition. But in 1908 he wrote his Second Quartet, the fourth movement of which is Schoenberg’s first real atonal work (during that time his wife, Mathilde Zemlinsky, left him and started an affair with the young painter Richard Gerstl. One wonders if there is a connection). In 1912 he followed up with a hugely influential Pierrot Lunaire, Op. 21, a setting of 21 poems by the Belgian-French poet Albert Giraud. It’s scored for a narrator (usually a soprano) and a chamber ensemble usually containing a clarinet, a flute, piano, and string instruments. This is also an atonal work, but it’s still not a 12-tone composition: he would develop the 12-tone system several years later.

This week is almost as rich with birthdays. William Boyce, one of the most important English composers of the 18th century was born around September 11, 1711 (he was baptized that day). Friedrich Kuhlau, a Danish composer, was born on September 11, 1786. These days he may not be performed very often in concert halls, but anybody who ever studied piano has most likely played one of his pieces. September 11th is also the birthday of the one of most interesting living composer, the Estonian Arvo Pärt. He was born in 1935. We’ll definitely write more about him at a later time. Clara Schumann, the wife of Robert Schumann, a pianist and composer and close friend of Johannes Brahms, was born on September 13, 1819. But the person we’d like to commemorate today at least to some degree is Arnold Schoenberg. He was born in Vienna on September 13, 1874 into a middle-class Jewish family. The only musical lessons he ever took were from the composer Alexander von Zemlinsky, his future brother-in-law. Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss were early supporters of Schoenberg, even though initially Schoenberg didn’t like Mahler’s music (he was "converted" after hearing Mahler’s Third Symphony). His first significant work was the string sextet Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night), written in 1899. Clearly a late-Romantic piece, it’s still a tonal composition. But in 1908 he wrote his Second Quartet, the fourth movement of which is Schoenberg’s first real atonal work (during that time his wife, Mathilde Zemlinsky, left him and started an affair with the young painter Richard Gerstl. One wonders if there is a connection). In 1912 he followed up with a hugely influential Pierrot Lunaire, Op. 21, a setting of 21 poems by the Belgian-French poet Albert Giraud. It’s scored for a narrator (usually a soprano) and a chamber ensemble usually containing a clarinet, a flute, piano, and string instruments. This is also an atonal work, but it’s still not a 12-tone composition: he would develop the 12-tone system several years later.

September 10, 2012. This week, very much like the last one, is abundant in anniversaries. The only person we wrote about last week was Anton Bruckner, but several other composers are also worth mentioning.. Darius Milhaud, a wonderful French composer and a member of Les Six, was born on September 4, 1892. Johann Christian Bach, the youngest of Johann Sebastian Bach’s sons and an influential composer of the Classical era, was born on September 5, 1735 (Mozart loved his music and wrote three piano concertos based on J.C. Bach’s keyboard sonatas). Anton Diabelli was also born on September 5, but half a century later, in 1781. Diabelli, a music publisher, wasn’t a good composer, but his ditzy waltz inspired Beethoven to write one of the most profound pieces in all of piano literature, the Diabelli Variations, Op. 120, boring if played poorly, sublime if played well. On the same day, but in 1867, Amy Beach, the first American woman to establish herself a classical composer, was born in Henniker, New Hampshire. September 8th is the anniversary of the great Czech composer Antonin Dvořák, who was born in 1841. We’ll write about Dvořák another time, but here’s his Romance, Op. 11. It’s performed by the violinist Natasha Korsakova, Charles Olivieri-Munroe conducting the North Czech Philharmonic Orchestra. And on September 9 of 1583, Girolamo Frescobaldi, one of the most interesting composers of the later Renaissance, was born in Ferrara. All of this in one week!

We’ll continue with Schoenberg and probably some other composers next week. In the mean time, you can listen to Verklärte Nacht here. It’s performed by Angelo Xiang Yu, violin, Yuuki Wong, violin, Hanna Lee, viola, Minkyung Sung, viola, and Karen Ouzounian, cello, Se-Doo Park, cello.

PermalinkSeptember 3, 2012. Anton Bruckner was born on September 4, 1824. This very fact gives one pause: Bruckner was born 9 year before Brahms! Brahms has been part of the canon for more than a century, one of the “Three Bs.” The music of Bruckner, while clearly of the Romantic tradition, feels new even today, fresh and absolutely original. Its history was difficult; initially, Vienna rejected it. Then, forty years after Bruckner’s death, the Nazis appropriated it, to some extent undermining it for the following generations. Still, thanks to Bruno Walter, Wilhelm Furtwängler, Karajan, Günter Wand, Sergiu Celibidache, and many other conductors, Bruckner’s music thrives today, becoming a touchstone of sorts for any great orchestra.

clearly of the Romantic tradition, feels new even today, fresh and absolutely original. Its history was difficult; initially, Vienna rejected it. Then, forty years after Bruckner’s death, the Nazis appropriated it, to some extent undermining it for the following generations. Still, thanks to Bruno Walter, Wilhelm Furtwängler, Karajan, Günter Wand, Sergiu Celibidache, and many other conductors, Bruckner’s music thrives today, becoming a touchstone of sorts for any great orchestra.

Bruckner was born in a small village outside of Linz, Austria. His first music teacher was his father, a local schoolmaster. He started playing the organ very early, and greatly improved in his second school, where the schoolmaster was an organist. After his father’s death, the 13 year-old Anton was sent to the monastery in Sankt-Florian, which had a great Baroque organ (see the photo below). He sometimes played the instrument during services. The following years were very difficult for Bruckner: his mother sent him to a teacher’s seminar, following which he had a number of low-paying teaching positions in St.-Florian and other towns. In 1855 Bruckner started studying musical theory and counterpoint with the Viennese composer, organist, and music theorist Simon Sechter. They mostly corresponded by mail, but Bruckner also made several visits to Vienna. That was also the time when Bruckner was introduced to the music of Wagner, which he liked and studied diligently. When Sechter died in 1868, the Vienna Conservatory offered his position to Bruckner. He accepted and taught there for a number of years. He later taught at the Vienna University. Bruckner wrote most of his symphonies while in Vienna (there was an unnumbered “study” symphony that he wrote while in St.-Florian, and started his 1st symphony there, although the revisions were written in Vienna).

A man of genius, Bruckner was a very unusual person, and very unusual as a composer. Mahler, who admired him, called him “half simpleton, half God.” He was a direct opposite of the archetypical creator, an auteur impervious to all criticism. Very humble and unsure of himself, he sought advice from everybody, from his students to conductors, and readily incorporated their suggestions. He significantly reworked many of his symphonies. Symphony no. 1 has three versions, as do symphonies 2 and 4. Symphony no. 3 has four different revisions. A provincial, he never got comfortable living in the capital. That the musical tastes in Vienna were dictated by the famous critic Eduard Hanslick, an admirer of Brahms and anti-Wagnerite, didn’t help either: Hanslick strongly disliked Bruckner’s music. Bruckner never married, although he made numerous proposals to very young girls. He died on October 11, 1896, at age 72, and was buried under his beloved organ in St.-Florian.

who admired him, called him “half simpleton, half God.” He was a direct opposite of the archetypical creator, an auteur impervious to all criticism. Very humble and unsure of himself, he sought advice from everybody, from his students to conductors, and readily incorporated their suggestions. He significantly reworked many of his symphonies. Symphony no. 1 has three versions, as do symphonies 2 and 4. Symphony no. 3 has four different revisions. A provincial, he never got comfortable living in the capital. That the musical tastes in Vienna were dictated by the famous critic Eduard Hanslick, an admirer of Brahms and anti-Wagnerite, didn’t help either: Hanslick strongly disliked Bruckner’s music. Bruckner never married, although he made numerous proposals to very young girls. He died on October 11, 1896, at age 72, and was buried under his beloved organ in St.-Florian.

We’ll hear the 3rd movement (Scherzo) of his Symphony no. 4. There’s a story connected to this symphony. Hans Richter, the famous conductor who by then had worked with Wagner, was rehearsing for the premier of the symphony. According to Richter, "When the symphony was over, Bruckner came to me, his face beaming with enthusiasm and joy. I felt him press a coin into my hand. 'Take this' he said, 'and drink a glass of beer to my health.'” Richter took the coin, and later wore it on his watch-chain. We’ll hear the original version (there are two others, each in more than one form. Even Mahler got into the game and created a version). It’s performed by Staatskapelle Dresden, Herbert Blomstedt conducting (to listen, click here, courtesy of YouTube).

PermalinkAugust 27, 2012. Nana Jashvili, a friend of the site, is a violin virtuoso recognized by the press and critics for the emotional intensity and the profound lyricism of her playing. Nana’s musical ability was developed under the influence of two cultures, Georgian and Russian. She was born in Tbilisi into a musical family. Her father, Luarsab Jashvili, a violinist and violist, was a professor at the Tbilisi Conservatory. He was Nana’s first teacher. Nana’s older sister, Marina Jashvili (Yashvili), who also took her first lessons with her father, became a famous violinist and a professor at the Moscow Conservatory. Marina died on July 9 of this year at the age of 79 after a long illness, and we mourn her passing.

Russian. She was born in Tbilisi into a musical family. Her father, Luarsab Jashvili, a violinist and violist, was a professor at the Tbilisi Conservatory. He was Nana’s first teacher. Nana’s older sister, Marina Jashvili (Yashvili), who also took her first lessons with her father, became a famous violinist and a professor at the Moscow Conservatory. Marina died on July 9 of this year at the age of 79 after a long illness, and we mourn her passing.

After studying with her father, Nana moved to Moscow and entered the class of the great violinist Leonid Kogan at the Moscow conservatory. As a student she won several national competitions. Then, at the age of seventeen, she had her triumphant breakthrough when she won the "Premier Grand Prix" at the International Jacques Thibaud Competition, the youngest winner ever. She was also awarded the "Prix Special" for the best interpretation of Maurice Ravel's "Tzigane." Several years later she also won the "Concours International de Montreal." Since then Nana has given concerts in the great music capitals in Europe, Canada and Japan. She has appeared as a soloist with the Concertgebouw orchestra of Amsterdam, the Gewandhaus orchestra of Leipzig, the Staatskapelle Dresden, the Orchestre de Paris and the Moscow and Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestras. She has worked with many great conductors, such as Claudio Abbado, Karl Böhm, Kurt Masur, Neeme Järvi, Yehudi Menuhin, Valerie Gergiev, Pavel Kogan, and Jansug Kakhidze. Nana Jashvili is a welcome guest artist on the concert stages at the summer festivals of Vienna, Bregenz and Copenhagen. Her repertoire extends from the Baroque to the contemporary. Her interpretation of the violin concerto op.36 by Schoenberg at the Vienna state opera was celebrated as an exceptional event. Nana is a professor at the Folkwang Hochschule in Essen. She plays a Nicola Gagliano violin.

Nana Jashvili’s recordings in our library suffer from many transfers from one media to another. Still, we’re sure that you’ll enjoy several of them. Here’s Béla Bartók’s Six Romanian Folk Dances. Tchaikovsky’s Valse Scherzo in C Major is here. Finally, the complete F-A-E Sonata, written by Albert Dietrich, Robert Schumann and Johannes Brahms, can be heard here. In all performances Nana is accompanied by the pianist Vladimir Skanavi. We hope to bring you more and better quality recordings in the near future.

PermalinkAugust 20, 2012. Claude Debussy. This week we celebrate a major event: the 150th anniversary of one of the greatest composers of the late 19th – early-20th century, Claude- Achille Debussy. He was born in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, a wealthy suburb of Paris (his family was not). He started his musical studies at the age of eight, in Nice, where his mother, then pregnant again, fled during the Prussian occupation of Paris in 1870. At the age of ten he entered the Paris conservatory and studied there for 11 years. In 1884 he won the Prix de Rome and moved to the French Academy in Rome for a four-year residence. He didn’t like it there, neither his companions nor the food. He submitted several pieces, one of which was a symphonic cantata La damoiselle élue. A pretty but rather straightforward piece with just a hint of the kind of harmonies that Debussy was to develop later, it was still labeled by the Academy as “bizarre.” In 1888 he visited Bayreuth to see Wagner’s Parsifal and Die Meistersinger and, deeply impressed, made a return a year later for Tristan und Isolde. 1889. As different as Wagner and Debussy are, it’s not surprising that the shimmering sonorities of Wagner’s orchestra affected the young Debussy. He later disavowed both the influence and Wagner’s music in general. Still, it seems that Wagner’s influence is discernable, and not only on Debussy’s only opera, Pelléas et Mélisande.

Achille Debussy. He was born in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, a wealthy suburb of Paris (his family was not). He started his musical studies at the age of eight, in Nice, where his mother, then pregnant again, fled during the Prussian occupation of Paris in 1870. At the age of ten he entered the Paris conservatory and studied there for 11 years. In 1884 he won the Prix de Rome and moved to the French Academy in Rome for a four-year residence. He didn’t like it there, neither his companions nor the food. He submitted several pieces, one of which was a symphonic cantata La damoiselle élue. A pretty but rather straightforward piece with just a hint of the kind of harmonies that Debussy was to develop later, it was still labeled by the Academy as “bizarre.” In 1888 he visited Bayreuth to see Wagner’s Parsifal and Die Meistersinger and, deeply impressed, made a return a year later for Tristan und Isolde. 1889. As different as Wagner and Debussy are, it’s not surprising that the shimmering sonorities of Wagner’s orchestra affected the young Debussy. He later disavowed both the influence and Wagner’s music in general. Still, it seems that Wagner’s influence is discernable, and not only on Debussy’s only opera, Pelléas et Mélisande.

By about 1890, Debussy had fully developed his own musical language. One of the first compositions to clearly manifest the new style was Suite bergamasque for piano (you can listen to it here, in the performance by the young Chinese pianist Xiang Zou). During that period Debussy was spending a lot of time in Stéphane Mallarmé symbolist salon. Four years later, influenced by a poem by Stéphane Mallarmé, Debussy wrote a symphonic poem Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune. The poem was later made into a famous ballet, choreographed by Vaslav Nijinsky. His only completed opera, Pelléas et Mélisande premiered in 1902. We had to borrow from YouTube to bring you an excerpt. It is here; Pierre Boulez conducts the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Donald McIntyre is Golaud, George Shirley – a Pelléas, Elisabeth Söderström is Mélisande. One of Debussy’s most popular compositions, three symphonic "sketches" titled La mer was written in 1903. A large number of piano compositions followed: Estampes, also in 1903, Children's Corner Suite in 1908, the first book of Préludes in1910 (the second book was written in 1913 and differs in style rather considerably). Debussy’s works were becoming more angular, with a larger number of unresolved dissonances, such as in this Etude No.11 "Pour les arpèges composes," (1915) performed here by the pianist Jiyeon Shin. And then in 1917 he wrote the violin sonata, which had much simpler harmonics (it is performed here by the Japanese violinist Mari Lee with Ieva Jokubaviciute on the piano). We don’t know if there was a general shift in Debussy’s compositional style: he wanted to write six sonatas but completed just three, for violin, for cello, and for flute, viola and harp (you can find all of them in our library). He died of cancer on March 25, 1918, while Paris was being heavily bombarded by the Germans. He was buried at the Père Lachaise with no public ceremony. The following year Debussy was re-interred at Passy, a small pretty cemetery behind the Trocadéro, in the 16th arrondissement.

PermalinkAugust 13, 2012. More mid-August birthdays. This week is full of anniversaries, even if most of them are of minor composers. Still, we think they should be noted. Sorabji (Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji), bor n on August 14, 1892, was an English composer of Parsi descent. He was quite controversial in his time and still is – among the people who’ve actually heard his music: some of Sorabji’s pieces are of extreme length. His piano sonata no. 5 runs for about five hours, and that’s not even his longest composition. Some critics think of him as one of the most interesting composers of the 20th century, while others, like The Guardian’s Andrew Clements, feel that Sorabji’s talent never matched his musical ambition. We have a piece by Sorabji, Pastiche on Habanera, but it is not very representative, so here is the first movement of his piano sonata no. 1 played by Marc-André Hamelin (courtesy of YouTube). If Hamelin though it worth studying and performing, that probably means that the sonata is not musically insignificant.

n on August 14, 1892, was an English composer of Parsi descent. He was quite controversial in his time and still is – among the people who’ve actually heard his music: some of Sorabji’s pieces are of extreme length. His piano sonata no. 5 runs for about five hours, and that’s not even his longest composition. Some critics think of him as one of the most interesting composers of the 20th century, while others, like The Guardian’s Andrew Clements, feel that Sorabji’s talent never matched his musical ambition. We have a piece by Sorabji, Pastiche on Habanera, but it is not very representative, so here is the first movement of his piano sonata no. 1 played by Marc-André Hamelin (courtesy of YouTube). If Hamelin though it worth studying and performing, that probably means that the sonata is not musically insignificant.

A totally different composer, the delightful Jacques Ibert, was born on August 15, 1890. He studied at the Paris conservatory, and took private composition and instrumentation lessons with André Gedalge; his fellow students were Arthur Honegger and Darius Milhaud, both influential members of Les Six. Ibert, though friendly with both, never joined the group. Ibert wrote operas, a ballet, several concertos, and a good deal of instrumental music. His songs are among the best in his output. Here’s Chanson à Dulcinée, from Chanson de Don Quichotte. It’s performed by the bass Liam Moran; Renate Rohlfing is on the piano.

Two other French composers were also born this week: Gabriel Pierné and Benjamin Godard, Pierné was born on August 16, 1863, Godard on August 18, 1849. Like Ibert, Godard studied at the Paris Conservatory, and like him, also won the prestigious Prix de Rome. He wrote operas, ballets and instrumental music, but not much of it is performed these days. But here is the first movement of his Sonata op.36 for violin and piano, and it sounds very nice. It’s played by the French violinist Elsa Grether; Eliane Reyes is on the piano. Benjamin Godard also studied at the Paris conservatory, and wrote an enormous number of compositions during his rather brief life (he died at the age of 45). There are recordings of his music on the market, but they’re few and far between. Here is a charming little morsel, Abandon. It’s performed by Albert Markov, violin, his son Alexander Markov, violin, with Dmitry Cogan on the piano.

And finally, from a totally different era, Antonio Salieri. He was born on August 18, 1750 in Legnano, Italy but spent most of his productive years in Vienna. Some day we’ll dedicate a whole piece to Salieri, but right now you can listen to part of his 26 Variations on the theme of La Folia. It’s performed by the London Mozart Players, Matthias Bamert, conductor (here, courtesy of YouTube).

Permalink