Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: October 28, 2024. Dittersdorf. Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf, an Austrian with a funny-sounding name, was a serious composer. Born Carl Ditters in Vienna on November 2nd of 1739, he acquired the noble title “von Dittersdorf” years later, while serving at the court of the Prince-Bishop of Breslau. His full surname became Ditters von Dittersdorf and since then he has been known as Dittersdorf. As a child, Carl studied the violin, and as a boy of 11, he was recruited to the orchestra of Prince Sachsen-Hildburghausen, one of the best in Vienna. When the prince left Vienna and disbanded his orchestra, Carl found employment with Count Giacomo Durazzo, director of Burgtheater, the imperial court theatre. Ditters played in the Burgtheater orchestra and soloed, often playing his own violin concertos. By that time a recognized virtuoso and composer, he accompanied Christoph Willibald Gluck on a trip to Italy. In 1765 he left the Burgtheater to accept the position of Kapellmeister for the Bishop of Grosswardein, succeeding Michael Haydn, Franz Joseph’s younger brother. He stayed there for four years, composing orchestral music and operas for the court theater.

November 2nd of 1739, he acquired the noble title “von Dittersdorf” years later, while serving at the court of the Prince-Bishop of Breslau. His full surname became Ditters von Dittersdorf and since then he has been known as Dittersdorf. As a child, Carl studied the violin, and as a boy of 11, he was recruited to the orchestra of Prince Sachsen-Hildburghausen, one of the best in Vienna. When the prince left Vienna and disbanded his orchestra, Carl found employment with Count Giacomo Durazzo, director of Burgtheater, the imperial court theatre. Ditters played in the Burgtheater orchestra and soloed, often playing his own violin concertos. By that time a recognized virtuoso and composer, he accompanied Christoph Willibald Gluck on a trip to Italy. In 1765 he left the Burgtheater to accept the position of Kapellmeister for the Bishop of Grosswardein, succeeding Michael Haydn, Franz Joseph’s younger brother. He stayed there for four years, composing orchestral music and operas for the court theater.

In 1769, after the bishop got into legal troubles, Ditters found employment with Count Schaffgotsch, Prince-Bishop of Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland, at that time a part of Silesia). The prince lived in exile in the castle of Johannisberg and built a theater next to it. Ditters, for all purposes a Kapellmeister except for the title, was tasked with improving the court orchestra, hiring the singers, and composing operas. During that time (in 1772) Ditters’ employer successfully petitioned Empress Maria-Theresia to have Ditters ennobled; thus, he became “von Dittersdorf.” Through trials and tribulations (in 1778 Austrian politics forced the prince to flee Johannisberg, leaving the composer to administer part of his estate), Dittersdorf continued to manage the orchestra and compose. While Schaffgotsch was out of the picture, Dittersdorf offered some of his operas to Prince Esterházy, Haydn’s employer.

With the prince temporarily gone and musical life in Johannisberg in decline, Dittersdorf spent much of his time in Vienna. His oratorio Giob, the twelve symphonies, and the opera Der Apotheker und der Doktor (here is the Overture and the first scene) were all well received. In 1785, while in Vienna, he played a quartet with Franz Joseph Haydn, Mozart, and his pupil, Johann Baptist Wanhal (Dittersdorf played the first violin, Haydn the second violin, while Mozart played the viola). Dittersdorf returned to Johannisberg in 1787, but musical life there was in shambles. Dittersdorf attempted to find a position with Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia, who liked his music, but an offer never came. He was formerly dismissed from Johannisberg in 1785. By the end of his life, Dittersdorf, penniless and suffering from gout, continued to compose; some of his best work was written during those years. He died in 1779 in the castle of one of his patrons.

Dittersdorf was a prolific composer of concertos, operas, symphonies, oratorios and chamber music. Some of his concertos were written for unusual instruments: for example, there are four (!) concertos for the double bass. Let’s listen to one of them, Concerto no. 2 for Double Bass and orchestra. Ödön Rácz is the soloist, he plays with the Franz Liszt Chamber Orchestra. Permalink

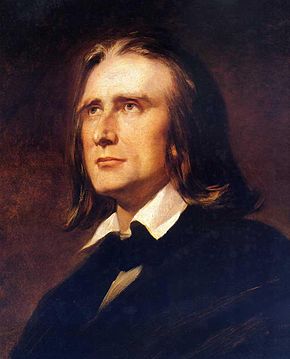

This Week in Classical Music: October 21, 2024. Lieberson and corrections. Last week our calendar got very much confused: we celebrated Franz Liszt, though his birthday, October 22nd, happens this week. There’s nothing wrong with celebrating Liszt early and often, so we’ll do it this week by playing one of his greatest compositions, the B minor Sonata. It’s a magnificent, grand Romantic piece, extremely popular in the early to mid-20th century when it was considered central to any virtuoso’s repertoire; it’s not played as often these days and its importance, so obvious before, is not as apparent. A one-movement piece, it is technically difficult and complex in structure. Liszt completed it in 1853 (the first sketches were written in 1842); it was premiered not by Liszt but Hans von Bülow, his student, in 1857. The sonata is dedicated to Robert Schumann, in return for Schumann dedicating his Fantasy in C major to Liszt some years earlier (Schumann died in 1856, between the Sonata’s completion and its premier). There are scores of excellent performances of the Sonata, so it’s nearly impossible to select the “best” one. Some recordings are more popular than others, for example, Krystian Zimerman’s from 1990 (and it’s indeed very good). And so are the recordings by Martha Argerich, Yuja Wang and Marc-André Hamelin. We’ll play an older recording, made live by the great pianist Sviatoslav Richter. He played it at the Aldeburgh Festival on June 21st of 1966 in the Aldeburgh parish church. We think it’s a profound performance.

happens this week. There’s nothing wrong with celebrating Liszt early and often, so we’ll do it this week by playing one of his greatest compositions, the B minor Sonata. It’s a magnificent, grand Romantic piece, extremely popular in the early to mid-20th century when it was considered central to any virtuoso’s repertoire; it’s not played as often these days and its importance, so obvious before, is not as apparent. A one-movement piece, it is technically difficult and complex in structure. Liszt completed it in 1853 (the first sketches were written in 1842); it was premiered not by Liszt but Hans von Bülow, his student, in 1857. The sonata is dedicated to Robert Schumann, in return for Schumann dedicating his Fantasy in C major to Liszt some years earlier (Schumann died in 1856, between the Sonata’s completion and its premier). There are scores of excellent performances of the Sonata, so it’s nearly impossible to select the “best” one. Some recordings are more popular than others, for example, Krystian Zimerman’s from 1990 (and it’s indeed very good). And so are the recordings by Martha Argerich, Yuja Wang and Marc-André Hamelin. We’ll play an older recording, made live by the great pianist Sviatoslav Richter. He played it at the Aldeburgh Festival on June 21st of 1966 in the Aldeburgh parish church. We think it’s a profound performance.

The American composer Peter Lieberson was born on October 26th of 1946 in New York. He studied composition with Milton Babbitt and Charles Wuorinen, some of the most “modernist” of American composers but his own music is much more tuneful. Lieberson wrote several concertos (three for the piano, one each for the horn, viola, and cello), an opera, and many chamber pieces, but he’s best remembered for his two song cycles, Rilke Songs for mezzo-soprano and piano, composed in 2001 and, from 2005, Neruda Songs for mezzo and orchestra. Both cycles were written for his wife, the wonderful mezzo Loraine Hunt Lieberson. Here, from the Rilke cycle, O ihr Zärtlichen (Oh you, tender ones). Loraine Hunt Lieberson is accompanied by Peter Serkin. And here is another song from the same cycle, Atmen, du unsichtbares Gedicht! (Breathe, you invisible poem!). It’s performed by the same artists.

Loraine Hunt Lieberson died from breast cancer in 2006 at the age of 52. Shortly after her death, Peter Lieberson was diagnosed with lymphoma. He continued to compose till the end of his life. Peter Lieberson died on April 23rd of 2011. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: October 14, 2024. Liszt and much more. Even though this week overflows with talent, we’ll be brief. First and foremost, Franz Liszt was born on October 22nd of 1811 in Doborján, a small village in the Kingdom of Hungary, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Now it’s a town called Raiding which lies in Austria. Liszt is considered Hungary’s national composer, though he never spoke Hungarian. His first language was German, he moved to Paris at the age of 12 and preferred to speak French for the rest of his life. But Hungarians have lived in Doborján for centuries, and Liszt was exposed to Hungarian music as a child. Even though Liszt was a thoroughly German composer heavily involved in German musical life, he used Hungarian (and Gipsy) tunes in many compositions, starting with many versions of Rákóczi-Marsch, the Hungarian national anthem at the time, to Hungarian Rhapsodies, nineteen of them for the piano, of which he later orchestrated six (or eight, but there are doubts about two of the orchestrations), to the symphonic poem Hungaria, and other pieces. Here is Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody no. 1, performed by Gyrgy (Georges) Cziffra, the great Hungarian pianist of Romani descent. The recording, later remastered, was originally made in 1957.

22nd of 1811 in Doborján, a small village in the Kingdom of Hungary, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Now it’s a town called Raiding which lies in Austria. Liszt is considered Hungary’s national composer, though he never spoke Hungarian. His first language was German, he moved to Paris at the age of 12 and preferred to speak French for the rest of his life. But Hungarians have lived in Doborján for centuries, and Liszt was exposed to Hungarian music as a child. Even though Liszt was a thoroughly German composer heavily involved in German musical life, he used Hungarian (and Gipsy) tunes in many compositions, starting with many versions of Rákóczi-Marsch, the Hungarian national anthem at the time, to Hungarian Rhapsodies, nineteen of them for the piano, of which he later orchestrated six (or eight, but there are doubts about two of the orchestrations), to the symphonic poem Hungaria, and other pieces. Here is Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody no. 1, performed by Gyrgy (Georges) Cziffra, the great Hungarian pianist of Romani descent. The recording, later remastered, was originally made in 1957.

Alexander von Zemlinsky, a very interesting Austrian composer whose music is rarely performed these days, was born on October 14th of 1871 in Vienna. Zemlinsky was central to the musical life of Vienna at the end of the 19th – early 20th century. He knew “everybody,” from Brahms and Mahler to Schoenberg; you can read more in one of our earlier posts here.

Luca Marenzio, an Italian composer of the Renaissance famous for his madrigals, was born in Northern Italy on October 18th, 1553. A century and a quarter later, on October 16th of 1679, the Czech composer Jan Dismas Zelenka was born near Prague. From 1709 to 1716 he worked in Dresden, first for Baron von Hartig and then for the royal court. He then moved to Vienna, later returning to the Dresden court. Zelenka knew Johann Sebastian Bach, who highly valued his music. Here are Lamentations for Maundy Thursday, from Zelenka’s The Lamentations of Jeremiah the Prophet. Jana Semerádová conducts Collegium Marianum.

A quarter of a century later, on October 18th of 1706, Baldassare Galuppi, was born on the island of Burano, next to Venice. He authored many operas, both comical, written to librettos of the playwright Carlo Goldoni, and “serious” (seria), often collaborating with Metastasio, one of the most famous librettists of the 18th century.

Finally, two Americans: Charles Ives, the most original American composer of the early 20th century, on October 20th of 1874, and Ned Rorem, on October 23rd of 1923. Ives’s 150th anniversary calls for a separate entry and we’ll do it soon. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: October 7, 2024. Schütz and more. Heinrich Schutz, the greatest German Renaissance predecessor of Johann Sebastian Bach, was born on October 8th of 1585 in Bad Köstritz, Thuringia. When Heinrich was five, his family moved to Weissenfels, where his father inherited an inn and became a mayor. Heinrich demonstrated musical talent from a very early age. In 1598, Maurice, the landgrave of Hesse-Kasse, a tiny principality then part of the Holy Roman Empire, stayed overnight in the family inn and heard Heinrich sing. Maurice, himself a musician and composer, was so impressed that he invited Heinrich to his court to study music and further his education (while at the court, Heinrich learned several languages, including Latin, Greek and French). Heinrich sang as a choir boy till his voice broke and then went to study law at Marburg. In 1609 he traveled to Venice to study music with Giovanni Gabrieli. Even though Gabrieli was 28 years older than Schütz, they became close friends (Gabrieli left him one of his rings when he died). The master died in 1612 and Schütz returned to Kassel. In 1614 the Elector of Saxony asked Schütz to come to Dresden. The famous Michael Praetorius was nominally in charge of music-making at the court but he had other responsibilities, so the elector was interested in Schütz’s service. Schütz moved to Dresden permanently in 1615. In 1619 he received the title of Hofkapellmeister. Soon after he published his first major work, Psalmen Davids (Psalms of David), a collection of 26 settings of psalms influenced, as one can hear, by Gabrieli. Here’s Psalm 128, “Wohl dem, der den Herren fürchte.” Cantus Cölln and Concerto Palatino are conducted by Konrad Junghänel.

1585 in Bad Köstritz, Thuringia. When Heinrich was five, his family moved to Weissenfels, where his father inherited an inn and became a mayor. Heinrich demonstrated musical talent from a very early age. In 1598, Maurice, the landgrave of Hesse-Kasse, a tiny principality then part of the Holy Roman Empire, stayed overnight in the family inn and heard Heinrich sing. Maurice, himself a musician and composer, was so impressed that he invited Heinrich to his court to study music and further his education (while at the court, Heinrich learned several languages, including Latin, Greek and French). Heinrich sang as a choir boy till his voice broke and then went to study law at Marburg. In 1609 he traveled to Venice to study music with Giovanni Gabrieli. Even though Gabrieli was 28 years older than Schütz, they became close friends (Gabrieli left him one of his rings when he died). The master died in 1612 and Schütz returned to Kassel. In 1614 the Elector of Saxony asked Schütz to come to Dresden. The famous Michael Praetorius was nominally in charge of music-making at the court but he had other responsibilities, so the elector was interested in Schütz’s service. Schütz moved to Dresden permanently in 1615. In 1619 he received the title of Hofkapellmeister. Soon after he published his first major work, Psalmen Davids (Psalms of David), a collection of 26 settings of psalms influenced, as one can hear, by Gabrieli. Here’s Psalm 128, “Wohl dem, der den Herren fürchte.” Cantus Cölln and Concerto Palatino are conducted by Konrad Junghänel.

Schütz lived in Dresden for the rest of his life, making periodic extended trips: in 1628 he went to Venice where he met Claudio Monteverdi who became a big influence. He also made several trips to Copenhagen, composing for the royal court. Schütz lived a long life: he died on November 6th of 1672 at the age of 87. Schütz composed mostly sacred choral music, although in 1627 he wrote what is considered the first German opera, Dafne. Even though the libretto survived, the score was lost years ago. Here’s one of Schütz’s Kleine Geistliche Konzerte (Little Sacred Concertos), composed in 1636. It’s called Bone Jesu Verbum Patris (Good Jesus, word of the Father). Tölzer Knabenchors is conducted by Gerhard Schmidt-Gaden.

Also this week: Giulio Caccini, a very important, if mostly forgotten Italian composer of the transitional period between the Renaissance and the Baroque, was born on October 8th of 1551, probably in Rome. A very popular “Ave Maria,” attributed to Caccini, was written by Vladimir Vavilov, a Russian guitarist, lutenist, composer and musical prankster who published several compositions ascribing them to composes of different eras. In 1970 Melodia issued an LP, “The Lute Music of the 16th and 17th Centuries” performed by Vavilov. Eight out of ten pieces were composed by him rather than composers indicated on the sleeve. Francesco da Milano, a lutenist and composer of the early 16th century, was Vavilov’s “favorite”: he composed six pieces, including a widely performed “Canzona,” and attributed all of them to the Italian. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: September 30, 2024. The Pianists. Last week we complained that there were too many composers of note; this time the situation is reversed: only Paul Dukas of The Sorcerer's Apprentice fame has a birthday in the next seven days. One of the few French Jewish composers, he was born on October 1st of 1865 in Paris. (And our apologies to the fans of Sir Charles Villiers Stanford, we know you are there).

The pianists are faring much better. Vladimir Horowitz was born on October 1st of 1903 in Kiev, the Russian Empire (now Kyiv, Ukraine) into a well-off Jewish family. At nine, Horowitz entered the Kiev Conservatory where he studied with Felix Blumenfeld, among others. He made his solo debut in 1920; around that time, he met the violinist Nathan Milstein, who was the same age and showed great talent. They played together in concerts (Vladimir’s sister Regina was Milstein’s accompanist). Both Horowitz and Milstein left Russia in 1925; Vladimir went first to Berlin and then to the US. His debut, on January 12th of 1928, when he played Tchaikovsky’s First piano concerto faster than the conductor Thomas Beecham would have it and dazzled the public with his technique, became legendary. That was the beginning of one of the most brilliant pianistic careers of the 20th century, even though Horowitz interrupted it four times, first from 1936 to 1938, then from 1953 to 1965, his longest absence from the concert stage, and again in 1969–74 and 1983–85. Altogether, he was away from the public for a long 21 years. That didn’t prevent him from becoming both a celebrity and one of the most interesting pianists of the century.

Horowitz was known to make small alterations to the score. One example is Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition: Horowitz felt that the composer, who wasn’t a pianist, didn’t use the instrument to its fullest extent. He added double octaves to some of Chopin’s pieces. But the real surprise was Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Sonata. Nobody would accuse Rachmaninov, one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century, of not knowing how to use the instrument. The sonata had two versions by then, the original, from 1930, and a reworking made in 1931. In 1940, Horowitz suggested some changes and Rachmaninov, who was in awe of Horowitz the pianist, consented to the alteration. Here it is, in Horowitz’s version, performed live in 1968 in Carnegie Hall. Horowitz always performed on his own Steinways, especially voiced by the maker. You can hear how, at around 12:25, in the middle of the second movement, a string breaks – on his own piano. After playing several more bars, Horowitz pauses (to applause) and waits for the technician to come on stage and remove the string. He then continues. Very often live recordings, despite some missed notes, are more exciting than ones made in a studio. This time the excitement reached a whole new level.

Vera Gornostayeva, a highly regarded Soviet/Russian pianist and pedagogue was born on October 1st of 1929 in Moscow. Alexander Slobodyanik, Pavel Egorov, Eteri Andjaparidze, Ivo Pogorelich, Sergei Babayan, Vassily Primakov, Lukas Geniušas, Vadym Kholodenko, Stanislav Khristenko, and others were her students.

Finally, Edwin Fischer, the Swiss pianist considered one of the greatest interpreters of Bach, was born in Basel on October 6th of 1886. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: September 23, 2024. Another Bountiful Week. We celebrated two 150th anniversaries in a row, those of Schoenberg and Holst, an unusual event. In the process, we missed several anniversaries. We won’t try to catch up, even if we’re sorry to have missed the names of Henry Purcell and Girolamo Frescobaldi, or that of our contemporary, Arvo Pärt. The reason is that this week in itself is very rich in talent. There are three composers from Eastern Europe: Andrzej Panufnik, Dimitri Shostakovich, and Komitas; the great Rameau, also another Frenchman, the controversial Florent Schmitt, and the American favorite, George Gershwin. And then there are the instrumentalists: two pianists, Glenn Gould and Alfred Cortot, and the violinist Jacques Thibaud. Two noted conductors were born this week, Colin Davis and Charles Munch, as was the tenor Fritz Wunderlich, one of the greatest German singers of the 20th century.

we missed several anniversaries. We won’t try to catch up, even if we’re sorry to have missed the names of Henry Purcell and Girolamo Frescobaldi, or that of our contemporary, Arvo Pärt. The reason is that this week in itself is very rich in talent. There are three composers from Eastern Europe: Andrzej Panufnik, Dimitri Shostakovich, and Komitas; the great Rameau, also another Frenchman, the controversial Florent Schmitt, and the American favorite, George Gershwin. And then there are the instrumentalists: two pianists, Glenn Gould and Alfred Cortot, and the violinist Jacques Thibaud. Two noted conductors were born this week, Colin Davis and Charles Munch, as was the tenor Fritz Wunderlich, one of the greatest German singers of the 20th century.

It’s impossible to give credit to all of them; also, in the past, we’ve posted elaborate entries about some (but not all) of the composers and musicians. For example, last year we dedicated an entry to Florent Schmitt, not necessarily a great composer but a very interesting, if contentious, figure in the history of French music. Jacques Thibaud and Charles Munch are two musicians we’ve failed to acknowledge in the past, we’ll correct this fault as soon as the opportunity presents itself.

We have written about Dmitri Shostakovich on several occasions, but he was such a talent that we feel the need to mention him separately. Born on September 25th of 1906 in St. Petersburg, he was admitted to the Conservatory at the age of 13 (the director, Alexander Glazunov, noticed his talent very early). His First Symphony premiered in 1926 to great acclaim – Shostakovich wasn’t yet twenty but became prominent not just in the Soviet Union but in the West, as Bruno Walter, Toscanini, Klemperer, Stokowski and other luminaries presented his symphony in Europe and the US. A talented pianist, in 1927 he participated in the inaugural Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw and earned a diploma (after the competition was over, Shostakovich spent a week in Berlin where he met Walter). In 1934 he wrote his second (after The Nose) opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, which premiered in Leningrad to great success. In 1935 it was staged in Cleveland, Philadelphia, New York, Zurich and other cities. In 1936, Stalin and his entourage attended a performance at the Bolshoi Theater and didn’t like it, after which it was denounced as “Muddle instead of Music” in Pravda, the main Soviet newspaper. That set a terrible pattern: Shostakovich would be rewarded and then criticized; he would then write something in the “Socialist Realism” style (he had a tremendous ear for that kind of music, you can listen to the “Festive Overture” to realize what we mean) then lauded and ostracized again. In 1948 Shostakovich was denounced by Stalin’s henchman, Zhdanov, together with Prokofiev and Khachaturian; he was dismissed from the Moscow Conservatory and was expected to be arrested at any moment. Then, one year later, he was instead sent to the Peace Conference in New York where he dutifully served as a mouthpiece for Soviet propaganda. That didn’t save him from the harsh criticism that his 24 Preludes and Fugues for the piano earned him from the Union of Soviet Composers.

Shostakovich started working on his Tenth Symphony in the late 1940s but finished it in several summer months in 1953, right after Stalin’s death. The Tenth is considered one of his greatest pieces, while the previous large-scale opus, the oratorio Song of the Forests, praising Stalin as a “Great Gardener” is one of the worst (and musically shallow) examples of his fawning productions, it’s painful to listen to. Here’s the first movement of Shostakovich’s Tenth Symphony. Vasily Petrenko leads the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra. Permalink