Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

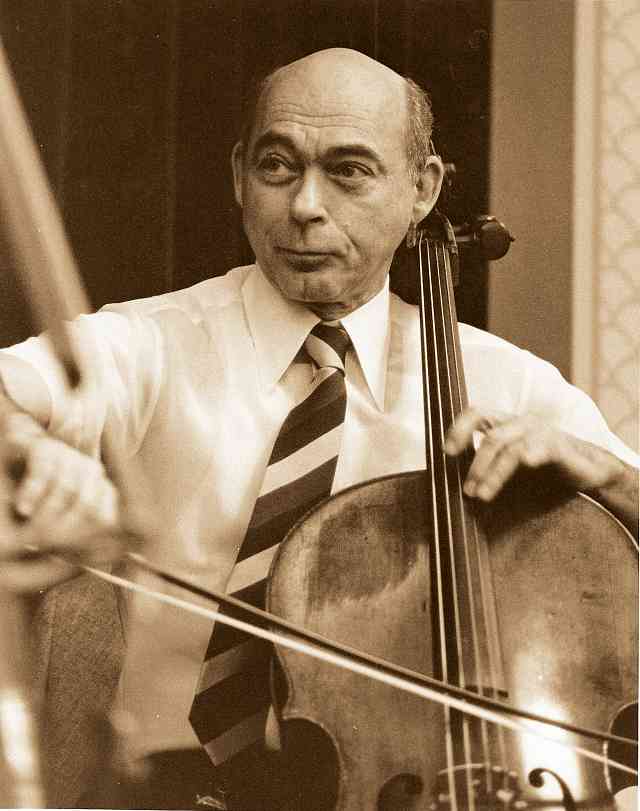

This Week in Classical Music: July 1, 2024. Sarker and more. We will celebrate János Starker’s 100th birthday on July 5th. One of the greatest cellists of the 20th century, Starker was born in Budapest in 1924 into a Jewish family. Starker, a child prodigy, entered the Budapest Academy at the age of seven and gave his first solo performance at 11. His teachers at the Academy were Leo Weiner, Zoltán Kodály, Béla Bartók and Ernő (Ernst von) Dohnányi – the pre-war Budapest Academy was a great music institution. Starker left the Academy in 1939, the year WWII started; he spent the wartime in Budapest and survived (the majority of the Budapest Jews were sent to Auschwitz in the last months of the war and perished there; two of his older brothers were murdered by the Nazis). After the war, with Budapest occupied by the Soviets, Starker joined the Budapest Philharmonic Orchestra as Principal Cello. In 1946 he left Hungary, going to Paris first and two years later to the US. He became the principal cellist of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra whose music director was a fellow Hungarian Jewish conductor Antal Doráti. From 1949 to 1953 Starker was the principal cello of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, then under the direction of Fritz Reiner, another Jewish musician from Budapest. From 1953 to 1958 he occupied the same position at the Chicago Symphony, which at that time was also led by Reiner. In 1958 Starker was appointed professor of cello at Indiana University, Bloomington; he remained there for the rest of his life. He toured widely and made many recordings.

born in Budapest in 1924 into a Jewish family. Starker, a child prodigy, entered the Budapest Academy at the age of seven and gave his first solo performance at 11. His teachers at the Academy were Leo Weiner, Zoltán Kodály, Béla Bartók and Ernő (Ernst von) Dohnányi – the pre-war Budapest Academy was a great music institution. Starker left the Academy in 1939, the year WWII started; he spent the wartime in Budapest and survived (the majority of the Budapest Jews were sent to Auschwitz in the last months of the war and perished there; two of his older brothers were murdered by the Nazis). After the war, with Budapest occupied by the Soviets, Starker joined the Budapest Philharmonic Orchestra as Principal Cello. In 1946 he left Hungary, going to Paris first and two years later to the US. He became the principal cellist of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra whose music director was a fellow Hungarian Jewish conductor Antal Doráti. From 1949 to 1953 Starker was the principal cello of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, then under the direction of Fritz Reiner, another Jewish musician from Budapest. From 1953 to 1958 he occupied the same position at the Chicago Symphony, which at that time was also led by Reiner. In 1958 Starker was appointed professor of cello at Indiana University, Bloomington; he remained there for the rest of his life. He toured widely and made many recordings.

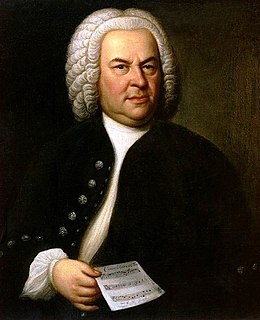

Starker recorded the complete set of Bach’s cello suites five times, the first recording made in 1950-52, the last – in 1997; that one won a Grammy. Here’s Johann Sebastian Bach’s Suite no. 5 in c minor. János Starker recorded it in New York on April 15th and 15th of 1963. There are many wonderful performances of this piece, we think this is one of the very best.

Starker died in Bloomington, Indiana, on April 28th of 2013.

We’d also like to mention several other names. Hans Werner Henze, an influential and prolific German composer, was born in Dresden on July 1st of 1926. And more than two centuries earlier, on July 2nd of 1714, another German, the great Christoph Willibald Gluck was born in the village of Erasbach, now part of Berching, a town in Bavaria.

We wanted to write about Hanns Eisler but Starker’s 100th anniversary intervened. Eisler, a composer of considerable talent, strong political opinions and an unusual life, was born on July 6th of 1898. We’ll write about him next week.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: June 17, 2024. Benedetto Marcello. Benedetto Marcello, born on June 24th of 1686, was an unusual composer: a Venetian patrician, he was an amateur musician. His father wanted Benedetto to become a lawyer, which he did, and was so successful in this profession that at the age of 20, he was admitted to the Great Council of Venice, and five years later elected to the Council of Forty, Venice’s Supreme Court. In 1730 he was sent to Pula in Istria, then part of the Venetian Republic and now in Croatia, to serve as Governor (it could’ve been an exile, but we don’t know). He stayed in Pula for eight years and then retired to Brescia as a papal chamberlain. He died there of tuberculosis in 1739. While a successful public servant (and also a poet), Marcello’s real love was music. He took some lessons in his youth but never had formal musical training. He probably started composing around 1710: as he was never associated with any musical institution, researchers have a difficult time dating his work. He wrote some instrumental pieces, but Marcello’s main interest was sacred music. A collection titled Estro poetico-armonico (it could be roughly translated as Poetic and Harmonic Inspiration) consists of 50 psalms (Salmi), several masses, and a Requiem. Here are Kyrie I and II, from the Requiem. Academia de li Musici is led by Filippo Maria Bressan. And here is one of his Salmi, Psalm 3, O Dio perché. Konrad Junghänel conducts the ensemble Cantus Cölln.

musician. His father wanted Benedetto to become a lawyer, which he did, and was so successful in this profession that at the age of 20, he was admitted to the Great Council of Venice, and five years later elected to the Council of Forty, Venice’s Supreme Court. In 1730 he was sent to Pula in Istria, then part of the Venetian Republic and now in Croatia, to serve as Governor (it could’ve been an exile, but we don’t know). He stayed in Pula for eight years and then retired to Brescia as a papal chamberlain. He died there of tuberculosis in 1739. While a successful public servant (and also a poet), Marcello’s real love was music. He took some lessons in his youth but never had formal musical training. He probably started composing around 1710: as he was never associated with any musical institution, researchers have a difficult time dating his work. He wrote some instrumental pieces, but Marcello’s main interest was sacred music. A collection titled Estro poetico-armonico (it could be roughly translated as Poetic and Harmonic Inspiration) consists of 50 psalms (Salmi), several masses, and a Requiem. Here are Kyrie I and II, from the Requiem. Academia de li Musici is led by Filippo Maria Bressan. And here is one of his Salmi, Psalm 3, O Dio perché. Konrad Junghänel conducts the ensemble Cantus Cölln.

An interesting tidbit: Faustina Bordoni, one of the most famous singers of the 18th century, Handel’s favorite, and the wife of the composer Johann Adolf Hasse, was “brought up under the protection of the brothers Alessandro and Benedetto Marcello,” as per Grove Music, and later received lessons from the brothers.

Handel’s favorite, and the wife of the composer Johann Adolf Hasse, was “brought up under the protection of the brothers Alessandro and Benedetto Marcello,” as per Grove Music, and later received lessons from the brothers.

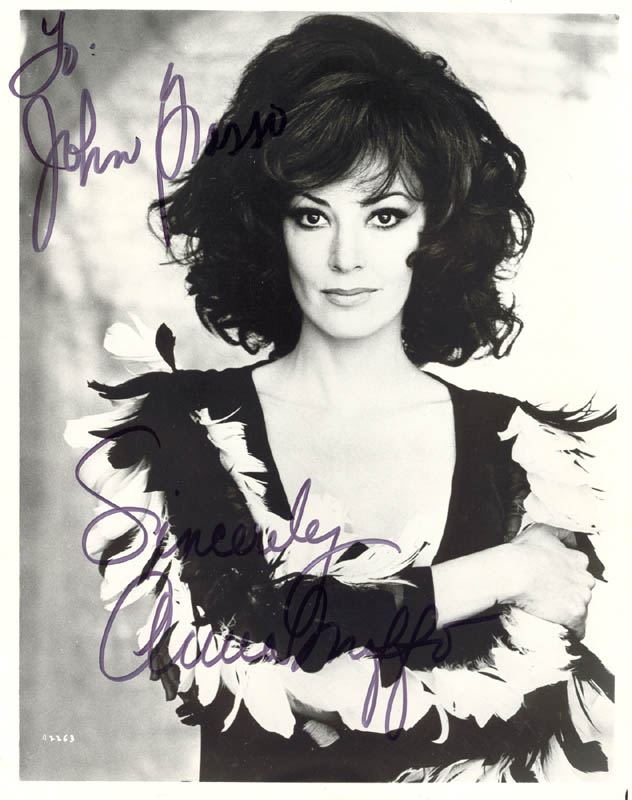

And speaking of singers, Anna Moffo was born on June 27th of 1932 in Philadelphia into a family of poor Italian immigrants. She studied at the Curtis and then in Italy. There, in 1955, she made her debut in Don Pasquale. Then, still just 23 and virtually unknown (but very pretty), she was offered the role of Cio-Cio San by RAI, the main Italian TV company. Madama Butterfly was telecast in January of 1956 and made Moffo famous overnight. Her career took off: she was asked to join Maria Callas, Giuseppe di Stefano and Rolando Panerai in the 1956 now-famous recording of La bohème, conducted by Karajan. In 1957 she premiered at the La Scala, and the Vienna State Opera, and in 1959 made her debut at the Metropolitan. Moffo had a beautiful lyric soprano voice; she also sang coloratura roles. Here she is, singing Sì. Mi chiamano Mimi, from Act I of La bohème. Tullio Serafin conducts the Rome Opera House Orchestra.

And so that we don’t forget, Claudio Abbado, one of our all-time favorite conductors, was born on June 26th of 1933. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: June 17, 2024. Stravinsky. Is it just us or did the music of Stravinsky lose some of its magic? Not that long ago it seemed that Stravinsky’s place at the very top of the musical Olympus was unshakable – but maybe listeners have had too much of The Rite of Spring and piano transcriptions of Petrushka. That Igor Stravinsky, born on June 17th of 1882 outside of St. Peterburg, was a genius is without a doubt. He had several creative phases: the initial, “Russian” phase, closely linked to Sergei Diaghilev, a great Russian impresario who established himself in Paris. It was during this period and owing to Diaghilev’s commissions that Stravinsky composed his most popular ballets: The Firebird (1910), Petrushka (1911), The Rite of Spring (1913), Les Noces (The Wedding, 1914-17). He made symphonic suites out of The Firebird and The Rite and transcribed parts of Petrushka for the piano; the public knows them better in these incarnations. He also composed two operas, The Nightingale in 1914 and Histoire du soldat in 1918, and, as with the ballets, he then used them to write orchestral pieces, Song of the Nightingale and a chamber suite from the Histoire. This was a remarkably fertile period: his music was unlike anything else ever composed (and therefore, scandalous, which only helped his fame), its harmonies and dissonances, its rhythms, the Russian exoticism – all of it captivated the public. By the end of WWI Stravinsky was acknowledged as one of the greatest living composers. And then, in the early 1920s he completely changed his style, the very nature of his compositions, replacing the wild, in-your-face energy of The Rite of Spring and other Russian-phase compositions with the Apollonian clarity, balance and emotional distance of the ballets Pulcinella, Apollo, and The Fairy's Kiss; the opera Oedipus rex, and several instrumental pieces. Later he wrote three symphonies, Symphony of Psalms (1930), Symphony in C (1940), and Symphony in Three Movements (1945). All three are composed mostly in the “neo-classical” style, though one can hear the younger Stravinsky in all of them. And then he made another turn, this time to the twelve-tone technique of his rival, Schoenberg. That was in the mid-1950s when Stravinsky was already in his 70s. In music, this capacity to reinvent himself is unique but he had a great counterpart in the arts, Pablo Picasso, who also went through many “periods”: Blue, Rose, Cubism, Neoclassical, Surrealist, and so on. For a long time, Picasso was considered the greatest artist of the 20th century, but recently we came across an article that questioned his primacy. Is the same happening to Stravinsky?

top of the musical Olympus was unshakable – but maybe listeners have had too much of The Rite of Spring and piano transcriptions of Petrushka. That Igor Stravinsky, born on June 17th of 1882 outside of St. Peterburg, was a genius is without a doubt. He had several creative phases: the initial, “Russian” phase, closely linked to Sergei Diaghilev, a great Russian impresario who established himself in Paris. It was during this period and owing to Diaghilev’s commissions that Stravinsky composed his most popular ballets: The Firebird (1910), Petrushka (1911), The Rite of Spring (1913), Les Noces (The Wedding, 1914-17). He made symphonic suites out of The Firebird and The Rite and transcribed parts of Petrushka for the piano; the public knows them better in these incarnations. He also composed two operas, The Nightingale in 1914 and Histoire du soldat in 1918, and, as with the ballets, he then used them to write orchestral pieces, Song of the Nightingale and a chamber suite from the Histoire. This was a remarkably fertile period: his music was unlike anything else ever composed (and therefore, scandalous, which only helped his fame), its harmonies and dissonances, its rhythms, the Russian exoticism – all of it captivated the public. By the end of WWI Stravinsky was acknowledged as one of the greatest living composers. And then, in the early 1920s he completely changed his style, the very nature of his compositions, replacing the wild, in-your-face energy of The Rite of Spring and other Russian-phase compositions with the Apollonian clarity, balance and emotional distance of the ballets Pulcinella, Apollo, and The Fairy's Kiss; the opera Oedipus rex, and several instrumental pieces. Later he wrote three symphonies, Symphony of Psalms (1930), Symphony in C (1940), and Symphony in Three Movements (1945). All three are composed mostly in the “neo-classical” style, though one can hear the younger Stravinsky in all of them. And then he made another turn, this time to the twelve-tone technique of his rival, Schoenberg. That was in the mid-1950s when Stravinsky was already in his 70s. In music, this capacity to reinvent himself is unique but he had a great counterpart in the arts, Pablo Picasso, who also went through many “periods”: Blue, Rose, Cubism, Neoclassical, Surrealist, and so on. For a long time, Picasso was considered the greatest artist of the 20th century, but recently we came across an article that questioned his primacy. Is the same happening to Stravinsky?

Here, from the late neo-classical period, is Stravinsky’s Symphony in Three Movements. In this 1985 live recording, Leonard Bernstein leads the Israel Philharmonic.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: June 10, 2024. On Place of Music in Culture, again. Edvard Grieg and Richard Strauss were born this week, the Norwegian on June 15th of 1843, and the German – on June 11th of 1864, but this is not what we want to write about this week. The pianist Bruce Liu played a recital in Chicago on Sunday a week ago. Mr. Liu is 27, he was born in Paris and raised in Montreal. Three years ago, he won the Chopin Piano Competition and since then his career has taken off. We heard good things about him, and his YouTube videos sounded interesting; we considered going to the concert but then circumstances intervened and we missed it. A couple of days later, interested in learning how Mr. Liu had played, we went online looking for a review. It turned out that not a single Chicago media outlet sent a reviewer to the concert: not the Chicago Tribune, not the Sun-Times, not even Larry Johnson’s Chicago Classical Review. We don’t know if Mr. Lui played well; what we do know is that the audience was very happy with him: he played six encores, all of them listed in the CSO updated program.

German – on June 11th of 1864, but this is not what we want to write about this week. The pianist Bruce Liu played a recital in Chicago on Sunday a week ago. Mr. Liu is 27, he was born in Paris and raised in Montreal. Three years ago, he won the Chopin Piano Competition and since then his career has taken off. We heard good things about him, and his YouTube videos sounded interesting; we considered going to the concert but then circumstances intervened and we missed it. A couple of days later, interested in learning how Mr. Liu had played, we went online looking for a review. It turned out that not a single Chicago media outlet sent a reviewer to the concert: not the Chicago Tribune, not the Sun-Times, not even Larry Johnson’s Chicago Classical Review. We don’t know if Mr. Lui played well; what we do know is that the audience was very happy with him: he played six encores, all of them listed in the CSO updated program.  Of course, the number of encores depends not only on the public’s enthusiasm but also on the performer – some prefer not to play any, as, for example, Sviatoslav Richter or Claudio Arrau later in their careers, others, likeEvgeny Kissin, enjoy playing them. Still, six encores at Orchestra Hall is a substantial number, which very likely reflects the audience’s appreciation, whether of the pianist's technique or musicianship, that we don’t know (that the technique is there is certain: listen to this half-minute Etude by Alkan).

Of course, the number of encores depends not only on the public’s enthusiasm but also on the performer – some prefer not to play any, as, for example, Sviatoslav Richter or Claudio Arrau later in their careers, others, likeEvgeny Kissin, enjoy playing them. Still, six encores at Orchestra Hall is a substantial number, which very likely reflects the audience’s appreciation, whether of the pianist's technique or musicianship, that we don’t know (that the technique is there is certain: listen to this half-minute Etude by Alkan).

And here’s another thing: while looking for a review, we came across one from the Stanford Daily. Musicians often perform on campuses, and it seems that student newspapers are better at covering classical music than the mainstream media (we saw several more of those). The review was enthusiastic if not very professional, but that was a minor problem. What caught our eye was a disclaimer that preceded the review itself. It said, “This article is a review and includes subjective thoughts, opinions and critiques.” Just think about it for a second: the readers, mostly students, were warned (or, in modern parlance, trigger-warned) that the article they’re about to read may include such scary things as “opinion and critique.” It is like the warning TV news programs give their thin-skinned viewer when covering wars, that some unpleasant things may be seen, probably because they don’t trust their audience to know what a war is. These warnings about thoughts, opinions and critiques are a direct consequence of the cultural metamorphosis on our campuses that also produced “safe spaces” and the notion of microaggression, and which, in the last years, spread out to society at large. It will take at least a generation to get rid of this inanity.

If anything, the program Bruce Liu played in Chicago was very imaginative: a sonata by Haydn, Chopin’s sonata no. 2, a piece by Kapustin, several pieces by Rameau, with Prokofiev’s Piano Sonata no 7 concluding the announced part of the program (the encores were by Bach, Chopin, Tchaikovsky and Liszt). Here’s one piece he played during the concert: Rameau’s Gavotte with six doubles from Nouvelles suites de pièces de clavecin. We think it’s very well-played, nuanced and in good taste. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: June 2, 2024. Argerich and Bartoli. For several weeks now we’ve been posting entries about composers, neglecting the performers. In a way, it’s understandable: somehow, we value the creative talent of composers higher than that of performers and interpreters. It’s not immediately obvious why a gift from God of one type should be considered more important than another, especially considering that, historically, this has not always been the case, but this is a topic for another time. Two supremely gifted women were born this week, the pianist Martha Argerich, on June 5th of 1941, and the singer Cecilia Bartoli, on June 4th of 1966. Argerich, one of the most celebrated musicians of our time, still performs, at the age of 83. Here’s part of her schedule for June of this year: three performances on June 13th through 1

understandable: somehow, we value the creative talent of composers higher than that of performers and interpreters. It’s not immediately obvious why a gift from God of one type should be considered more important than another, especially considering that, historically, this has not always been the case, but this is a topic for another time. Two supremely gifted women were born this week, the pianist Martha Argerich, on June 5th of 1941, and the singer Cecilia Bartoli, on June 4th of 1966. Argerich, one of the most celebrated musicians of our time, still performs, at the age of 83. Here’s part of her schedule for June of this year: three performances on June 13th through 1 5th of Beethoven’s Second Piano Concerto in Rome at the Auditorium Il Parco Della Musica, then several concerts in Hamburg – playing Ravel’s La Valse for two pianos with Sergio Tiempo on the 20th, the next day playing chamber pieces of Schumann, Beethoven and Shostakovich, and the following day giving a concert of Chopin pieces. And it goes like that for the rest of the month, almost every day: Schumann’s Dichterliebe with Ema Nikolovska, Beethoven’s Triple Concerto with Gil Shaham and Edgar Moreau, some Debussy, Schubert and Mussorgsky, and on the last day of the month, Shostakovich’s Concerto no. 1, for piano and trumpet with Sergei Nakariakov, a Russian-Israeli, Paris-based trumpet virtuoso. What amazing energy! We wish her many years to come.

5th of Beethoven’s Second Piano Concerto in Rome at the Auditorium Il Parco Della Musica, then several concerts in Hamburg – playing Ravel’s La Valse for two pianos with Sergio Tiempo on the 20th, the next day playing chamber pieces of Schumann, Beethoven and Shostakovich, and the following day giving a concert of Chopin pieces. And it goes like that for the rest of the month, almost every day: Schumann’s Dichterliebe with Ema Nikolovska, Beethoven’s Triple Concerto with Gil Shaham and Edgar Moreau, some Debussy, Schubert and Mussorgsky, and on the last day of the month, Shostakovich’s Concerto no. 1, for piano and trumpet with Sergei Nakariakov, a Russian-Israeli, Paris-based trumpet virtuoso. What amazing energy! We wish her many years to come.

Cecilia Bartoli was born in Rome and studied there at the Santa Cecilia Conservatory. She made her opera debut at the age of 21, and one year later was already widely known in Europe. Bartoli has a rare voice, a coloratura mezzo-soprano, with a huge range and unique flexibility. This allowed her to sing not just the standard mezzo repertoire, such as Rosina in The Barber of Seville, Zerlina in Don Giovanni, Cherubino in The Marriage of Figaro, or Dorabella in Così fan tutte, all of which she did extremely well;, she also brought to life Baroque music rarely heard before, and almost never performed on such a level, not since the end of the era of castrati. Here, for example, is Bartoli performing two arias from Vivaldi’s opera Griselda. First, Agitata da due venti (Moved by the wind), recorded in 1998 with the ensemble Sonatori de la Gioiosa Marca, and next, Dopo Un'orrida Procella (After a horrible storm), recorded one year later with Il Giardino Armonico under the direction of Giovanni Antonini. We find Bartoli’s musicianship and technique incredible.

Here are the names of three conductors born this week, Yevgeny Mravinsky, born June 4th of 1903, who led the Leningrad Philharmonic for 50 years and was a great interpreter of the music of Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich; a wonderful Mahlerian, the German conductor Klaus Tennstedt (June 6th of 1926); and the Jewish Hungarian-American, George Szell (June 7th of 1897), who, among other things, made the Cleveland Orchestra into one of the best in the world. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: May 27, 2024. Joachim Raff. The German composer Joachim Raff was born on this day in 1822. For all the years we’ve been writing these entries, not once did we mention his name. Of course, there are thousands of composers whose names escaped our attention, but these are usually second and third-tier; what makes Raff’s case unusual is that at the height of his popularity in the 1860s and 70s, his work was more popular than that of any other living German composer, including Bruckner (not at all popular during his lifetime) and Brahms. Soon after his death, Raff’s music was forgotten, and very few pieces are still performed today; it’s interesting to look back to see what attracted the sophisticated German public to his work and why it was abandoned so quickly. Raff, of German descent, was born in Switzerland, where his father escaped to avoid conscription during the Napoleonic wars. He was trained as a teacher, but as a musician, Raff was mostly self-taught (he became an accomplished pianist and organist); he started composing in his early 20s. Raff sent some of his work to Mendelssohn, who praised it and helped to get it published. In 1845 Raff, who lived in Zurich, met the great Franz Liszt. Liszt took a liking to him and found Raff a job in Cologne in a piano and music store. While in Cologne, Raff met Mendelssohn face-to-face and stayed in contact with Liszt. In 1847 he moved to Stuttgart and met the young Hans von Bülow. Bülow would later go to study with Liszt, marry his daughter Cosima, and then lose her to Wagner. He would also be one of the 19th-century best pianists and conductors. Bülow and Raff became best friends; Bülow had strong opinions and a sharp tongue and sometimes criticized Raff’s compositions but their friendship survived for the rest of Raff’s life.

we mention his name. Of course, there are thousands of composers whose names escaped our attention, but these are usually second and third-tier; what makes Raff’s case unusual is that at the height of his popularity in the 1860s and 70s, his work was more popular than that of any other living German composer, including Bruckner (not at all popular during his lifetime) and Brahms. Soon after his death, Raff’s music was forgotten, and very few pieces are still performed today; it’s interesting to look back to see what attracted the sophisticated German public to his work and why it was abandoned so quickly. Raff, of German descent, was born in Switzerland, where his father escaped to avoid conscription during the Napoleonic wars. He was trained as a teacher, but as a musician, Raff was mostly self-taught (he became an accomplished pianist and organist); he started composing in his early 20s. Raff sent some of his work to Mendelssohn, who praised it and helped to get it published. In 1845 Raff, who lived in Zurich, met the great Franz Liszt. Liszt took a liking to him and found Raff a job in Cologne in a piano and music store. While in Cologne, Raff met Mendelssohn face-to-face and stayed in contact with Liszt. In 1847 he moved to Stuttgart and met the young Hans von Bülow. Bülow would later go to study with Liszt, marry his daughter Cosima, and then lose her to Wagner. He would also be one of the 19th-century best pianists and conductors. Bülow and Raff became best friends; Bülow had strong opinions and a sharp tongue and sometimes criticized Raff’s compositions but their friendship survived for the rest of Raff’s life.

Raff followed Lisz to Weimar, where, as Liszt’s protégé, he entered the circle of “New German composers,” an influential group that included Wagner. There he met Brahms and the famous violinist and conductor Josef Joachim. He also met his future wife, actress Doris Genast. Things looked positive for a while but eventually, it became clear that opportunities in Weimer were limited. And so, even though Liszt aided Raff financially and supported his musical efforts, Raff decided to leave Weimar. Around 1858, he found a position in Wiesbaden and moved there. It was in Wiesbaden that Raff composed the majority of his work and achieved public recognition. His First Symphony, a 70-minute composition subtitled An das Vaterland (To the Fatherland) was composed between 1859 and 1861 and was well received. And so were many other works that followed: his Third Symphony (Im Walde, In the Forest) became one of the most often-performed symphonies of its time, and the Fifth (Lenore) was also received enthusiastically. His piano and violin concertos became popular and the chamber pieces were widely performed. It’s even said that Raff’s music had some influence on Tchaikovsky and Richard Strauss. It’s not clear why Raff was forgotten so quickly. Indeed, he was not very original, much of his music was too long, and he wrote too much of it. But the same could be said about some 19th-century composers who are still feted today. And some of Raff’s music is very pretty. These days very few of his pieces are played, his Fifth Symphony, Lenore, is one of them. You can judge for yourself whether it’s worth it. Here’s the 1st movement of this symphony. Yondani Butt is leading the Philharmonia Orchestra. And if you want to hear more, here’s the rest of the symphony: the 2nd, 3rd and 4th movements.

Permalink