Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: September 23, 2024. Another Bountiful Week. We celebrated two 150th anniversaries in a row, those of Schoenberg and Holst, an unusual event. In the process, we missed several anniversaries. We won’t try to catch up, even if we’re sorry to have missed the names of Henry Purcell and Girolamo Frescobaldi, or that of our contemporary, Arvo Pärt. The reason is that this week in itself is very rich in talent. There are three composers from Eastern Europe: Andrzej Panufnik, Dimitri Shostakovich, and Komitas; the great Rameau, also another Frenchman, the controversial Florent Schmitt, and the American favorite, George Gershwin. And then there are the instrumentalists: two pianists, Glenn Gould and Alfred Cortot, and the violinist Jacques Thibaud. Two noted conductors were born this week, Colin Davis and Charles Munch, as was the tenor Fritz Wunderlich, one of the greatest German singers of the 20th century.

we missed several anniversaries. We won’t try to catch up, even if we’re sorry to have missed the names of Henry Purcell and Girolamo Frescobaldi, or that of our contemporary, Arvo Pärt. The reason is that this week in itself is very rich in talent. There are three composers from Eastern Europe: Andrzej Panufnik, Dimitri Shostakovich, and Komitas; the great Rameau, also another Frenchman, the controversial Florent Schmitt, and the American favorite, George Gershwin. And then there are the instrumentalists: two pianists, Glenn Gould and Alfred Cortot, and the violinist Jacques Thibaud. Two noted conductors were born this week, Colin Davis and Charles Munch, as was the tenor Fritz Wunderlich, one of the greatest German singers of the 20th century.

It’s impossible to give credit to all of them; also, in the past, we’ve posted elaborate entries about some (but not all) of the composers and musicians. For example, last year we dedicated an entry to Florent Schmitt, not necessarily a great composer but a very interesting, if contentious, figure in the history of French music. Jacques Thibaud and Charles Munch are two musicians we’ve failed to acknowledge in the past, we’ll correct this fault as soon as the opportunity presents itself.

We have written about Dmitri Shostakovich on several occasions, but he was such a talent that we feel the need to mention him separately. Born on September 25th of 1906 in St. Petersburg, he was admitted to the Conservatory at the age of 13 (the director, Alexander Glazunov, noticed his talent very early). His First Symphony premiered in 1926 to great acclaim – Shostakovich wasn’t yet twenty but became prominent not just in the Soviet Union but in the West, as Bruno Walter, Toscanini, Klemperer, Stokowski and other luminaries presented his symphony in Europe and the US. A talented pianist, in 1927 he participated in the inaugural Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw and earned a diploma (after the competition was over, Shostakovich spent a week in Berlin where he met Walter). In 1934 he wrote his second (after The Nose) opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, which premiered in Leningrad to great success. In 1935 it was staged in Cleveland, Philadelphia, New York, Zurich and other cities. In 1936, Stalin and his entourage attended a performance at the Bolshoi Theater and didn’t like it, after which it was denounced as “Muddle instead of Music” in Pravda, the main Soviet newspaper. That set a terrible pattern: Shostakovich would be rewarded and then criticized; he would then write something in the “Socialist Realism” style (he had a tremendous ear for that kind of music, you can listen to the “Festive Overture” to realize what we mean) then lauded and ostracized again. In 1948 Shostakovich was denounced by Stalin’s henchman, Zhdanov, together with Prokofiev and Khachaturian; he was dismissed from the Moscow Conservatory and was expected to be arrested at any moment. Then, one year later, he was instead sent to the Peace Conference in New York where he dutifully served as a mouthpiece for Soviet propaganda. That didn’t save him from the harsh criticism that his 24 Preludes and Fugues for the piano earned him from the Union of Soviet Composers.

Shostakovich started working on his Tenth Symphony in the late 1940s but finished it in several summer months in 1953, right after Stalin’s death. The Tenth is considered one of his greatest pieces, while the previous large-scale opus, the oratorio Song of the Forests, praising Stalin as a “Great Gardener” is one of the worst (and musically shallow) examples of his fawning productions, it’s painful to listen to. Here’s the first movement of Shostakovich’s Tenth Symphony. Vasily Petrenko leads the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: September 16, 2024. Gustav Holst. We must admit that we’re not big fans of Gustav Holst’s music, though we readily acknowledge the talent of this English composer. Neither are we greatly enamored with the music of his best friend Ralph Vaughan Williams, or the older and more famous Edgar Elgar, or practically any other British composer of the late 19th - early 20th century. We know they’re all very dear to the English heart, but we find the music composed during the same period in Germany, Austria, France and Russia much more interesting and more to our taste. Nevertheless, September 21st marks the 150th anniversary of Holst’s birth, and obviously, we should recognize this important date. (History plays games with us: just last week we celebrated the 150th anniversary of Arnold Schoenberg, creating an interesting if unintended juxtaposition).

composer. Neither are we greatly enamored with the music of his best friend Ralph Vaughan Williams, or the older and more famous Edgar Elgar, or practically any other British composer of the late 19th - early 20th century. We know they’re all very dear to the English heart, but we find the music composed during the same period in Germany, Austria, France and Russia much more interesting and more to our taste. Nevertheless, September 21st marks the 150th anniversary of Holst’s birth, and obviously, we should recognize this important date. (History plays games with us: just last week we celebrated the 150th anniversary of Arnold Schoenberg, creating an interesting if unintended juxtaposition).

Holst was born in Cheltenham, a spa town in the Cotswolds. His father’s side of the family was of German descent and musical, his mother was English. Interested in music from an early age, Holst studied composition at the Royal College of Music with the prominent composer Charles Villiers Stanford. Till The Planets were first performed in 1918, Holst had to support himself by teaching and playing the trombone in different orchestras; none of his early compositions achieved popular success. That all changed with The Planets. This is an unusual piece, as few seven-movement symphonic works have ever been composed. Holst started working on it in 1913 and completed the suite in 1917. The premier, held on September 29th of 1918, less than six weeks before the end of WWI, was conducted by Adrian Boult. Boult, then 28 years old, lived to the ripe age of 92 and conducted almost till the end. The concert took place in the old Queen’s Hall, then the main performance venue in London (the hall was destroyed by a German bomb in 1941). It was a semi-private affair, as only selected listeners were invited, and the hall was half empty. While the structure and the musical language of the composition were quite unusual, many of the reviews were positive, and even those newspapers that first panned the music changed their minds soon after. Even though several subsequent performances played only four or five movements of the whole work, The Planets’ reputation grew with every concert and solidified soon after. In 1922 Holst himself conducted the first recording of the suite; more than 80 recordings have been made since then.

Here is the first movement of The Planets, Mars, the Bringer of War. Herbert von Karajan conducts the Vienna Philharmonic. And here, with the same performers, is the very contrasting last movement of the suite, Neptune, the Mystic, with a hidden chorus. This recording was issued in 1962.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: September 9, 2024. Schoenberg 150. Last week we celebrated the 200th anniversary of Bruckner’s birth. This week is no less important: September 13th marks the 150th anniversary of one of the most consequential composers in the history of Western music, Arnold Schoenberg. Schoenberg was born in Leopoldstadt, a heavily Jewish district of Vienna, in 1874. Two years ago we published a series of four entries about him, here, here, here, and here, so we won’t go into the details of his life today. Even though Schoenberg’s music is still played only occasionally, especially pieces from his atonal and twelve-tone phases, it's generally accepted that he was a seminal figure in the history of music, and, given that it’s such an important date, many institutions around the world celebrate his anniversary with festivals and performances. Vienna, his birthplace, is exceptional in this regard, setting up exhibitions, a film festival, and many concerts. On Schoenberg’s birthday, September 13th, and the following day, the Vienna Symphony, three choruses and soloists, all under the direction of Petr Popelka, will perform his Gurre-Lieder, an oratorio in three parts, composed between 1900 and 1903 but finished in 1911 (Gurre-Lieder, together with Verklärte Nacht, is considered the most important of Schoenberg’s pieces from his tonal, late-Romantic period). Germany, where Schoenberg lived for years, mounted more events and performances than any other country, they’re spread among many cities. California, Schoenberg’s home for the last 16 years of his life, also celebrates the event with several concerts. The Chicago Symphony, on the other hand, completely ignored the anniversary. In general, Europe seems to be much more interested in Schoenberg than the US. Even in war-torn Ukraine, they plan to have two Schoenberg concerts, both in Kyiv. New recordings are also being made. Fabio Luisi, the Italian conductor who leads three orchestras at the same time - the Danish National Symphony, the Dallas Symphony and the NHK Symphony in Japan, is embarking on the most ambitious project. He plans to record all of Schoenberg’s symphonic output with the Danish NSO and distribute it on the Deutsche Grammophon label.

the 150th anniversary of one of the most consequential composers in the history of Western music, Arnold Schoenberg. Schoenberg was born in Leopoldstadt, a heavily Jewish district of Vienna, in 1874. Two years ago we published a series of four entries about him, here, here, here, and here, so we won’t go into the details of his life today. Even though Schoenberg’s music is still played only occasionally, especially pieces from his atonal and twelve-tone phases, it's generally accepted that he was a seminal figure in the history of music, and, given that it’s such an important date, many institutions around the world celebrate his anniversary with festivals and performances. Vienna, his birthplace, is exceptional in this regard, setting up exhibitions, a film festival, and many concerts. On Schoenberg’s birthday, September 13th, and the following day, the Vienna Symphony, three choruses and soloists, all under the direction of Petr Popelka, will perform his Gurre-Lieder, an oratorio in three parts, composed between 1900 and 1903 but finished in 1911 (Gurre-Lieder, together with Verklärte Nacht, is considered the most important of Schoenberg’s pieces from his tonal, late-Romantic period). Germany, where Schoenberg lived for years, mounted more events and performances than any other country, they’re spread among many cities. California, Schoenberg’s home for the last 16 years of his life, also celebrates the event with several concerts. The Chicago Symphony, on the other hand, completely ignored the anniversary. In general, Europe seems to be much more interested in Schoenberg than the US. Even in war-torn Ukraine, they plan to have two Schoenberg concerts, both in Kyiv. New recordings are also being made. Fabio Luisi, the Italian conductor who leads three orchestras at the same time - the Danish National Symphony, the Dallas Symphony and the NHK Symphony in Japan, is embarking on the most ambitious project. He plans to record all of Schoenberg’s symphonic output with the Danish NSO and distribute it on the Deutsche Grammophon label.

We’ll celebrate Schoenberg’s anniversary with two different pieces, his Five Pieces for Orchestra, op. 16, from 1909, and Four Orchestral Songs for soprano and large orchestra, composed between 1913 and 1916. Opus 16 was written while Schoenberg was still working within the tonal idiom, although by then he was already using “extreme chromaticism.” This music is clearly beyond the Romanticism of his earlier works. Here it is, performed by the London Symphony, Robert Craft conducting.

The admittedly more difficult Four Songs are the last ones from Schoenberg’s free atonal period, the one that followed his Romantic beginnings. After that, and for a long period, he wrote music using his own newly developed twelve-tone technique (at the end of his life he would sometimes revert to tonal compositions). The singer in this recording is the mezzo Catherine Wyn-Rogers. Robert Craft is again the conductor, in this case leading the Philharmonia Orchestra.

A note: while we’re celebrating Arnold Schoenberg, we remember that this week is rich in important birthdays, Henry Percell and Girolamo Frescobaldi’s among them, and also Clara Schumann’s and Arvo Pärt’s, who will be 89 on September 11th. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: September 2, 2024. Bruckner 200. Several composers were born this week, the first and foremost of them – Anton Bruckner. We’re celebrating his 200th anniversary: Bruckner was born September 4th of 1824 in Ansfelden, a village outside of Linz. We love Bruckner and have written about him on many occasions, him personally (here, for example), as well as his music (here, about one of the several symphonies that we’ve touched upon). We had mentioned Bruckner’s notorious lack of confidence often: he was convinced that professional musicians knew and understood his music better than he did himself. This resulted in Bruckner rewriting major parts of practically all his symphonies over and over, sometimes following innocuous comments. In best cases we’re left with many editions of the same symphony: for example, he revised his Symphony no. 4, one of his most popular symphonies today, five times, and there are numerous editions of each revision, around 10 of them altogether. The Fourth was composed in 1872, the first revision followed one year later while the last one – in 1892, twenty years after the original composition was put to paper. But sometimes, things turned out much worse. Between January and September of 1869, Bruckner composed a symphony. It followed Symphony no. 1, which Bruckner completed in 1866 (as usual, many versions would follow, all the way to 1891), so he called it Symphony no. 2 (in D minor). Then, Otto Dessoff, a minor composer but a noted conductor who then led the Vienna Philharmonic, made a comment, and we’ll quote Georg Tintner, an Austrian conductor, on the consequences. "How an off-hand remark, when directed at a person lacking any self-confidence, can have such catastrophic consequences! Bruckner, who all his life thought that able musicians (especially those in authority) knew better than he did, was devastated when Otto Dessoff (then the conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic) asked him about the first movement: "But where is the main theme?" In the aftermath, Bruckner failed to submit the Symphony for a performance, and some years later, while reviewing his output, wrote "annullirt" ("nullified") on the front page and replaced the number (no. 2) with a symbol "∅" which was later interpreted as zero (0). Since then, the symphony acquired the designation of “Symphony no. 0.” The first performance was made in 1924, 55 years after it was completed, and the first recording – some nine years later, in 1933. There are many wonderful recordings of the symphony, one of them made by Bernard Haitink in 1966 with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. You can listen to it here.

anniversary: Bruckner was born September 4th of 1824 in Ansfelden, a village outside of Linz. We love Bruckner and have written about him on many occasions, him personally (here, for example), as well as his music (here, about one of the several symphonies that we’ve touched upon). We had mentioned Bruckner’s notorious lack of confidence often: he was convinced that professional musicians knew and understood his music better than he did himself. This resulted in Bruckner rewriting major parts of practically all his symphonies over and over, sometimes following innocuous comments. In best cases we’re left with many editions of the same symphony: for example, he revised his Symphony no. 4, one of his most popular symphonies today, five times, and there are numerous editions of each revision, around 10 of them altogether. The Fourth was composed in 1872, the first revision followed one year later while the last one – in 1892, twenty years after the original composition was put to paper. But sometimes, things turned out much worse. Between January and September of 1869, Bruckner composed a symphony. It followed Symphony no. 1, which Bruckner completed in 1866 (as usual, many versions would follow, all the way to 1891), so he called it Symphony no. 2 (in D minor). Then, Otto Dessoff, a minor composer but a noted conductor who then led the Vienna Philharmonic, made a comment, and we’ll quote Georg Tintner, an Austrian conductor, on the consequences. "How an off-hand remark, when directed at a person lacking any self-confidence, can have such catastrophic consequences! Bruckner, who all his life thought that able musicians (especially those in authority) knew better than he did, was devastated when Otto Dessoff (then the conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic) asked him about the first movement: "But where is the main theme?" In the aftermath, Bruckner failed to submit the Symphony for a performance, and some years later, while reviewing his output, wrote "annullirt" ("nullified") on the front page and replaced the number (no. 2) with a symbol "∅" which was later interpreted as zero (0). Since then, the symphony acquired the designation of “Symphony no. 0.” The first performance was made in 1924, 55 years after it was completed, and the first recording – some nine years later, in 1933. There are many wonderful recordings of the symphony, one of them made by Bernard Haitink in 1966 with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. You can listen to it here.

Bruckner had many detractors, Johannes Brahms being the foremost. Antonin Dvořák, Brahms’s follower and beneficiary, was also one of them. Dvořák was born on September 8th of 1841 in Nelahozeves, a village near Prague, then part of the Austrian Empire. His Symphony No.9, "From the New World," ranks highly on many lists of “most popular symphonies.” Clearly, Dvořák was a talented composer, but compared to Bruckner’s they sound somewhat trite, whereas Bruckner’s are fresh and, even now, innovative.

This was a rather special week: Darius Milhaud, Johann Christian Bach, Giacomo Meyerbeer, John Cage, Amy Beach, Isabella Leonarda, and Hernando De Cabezon were all born within these seven days. We’ll come back to some of them at a later date.Permalink

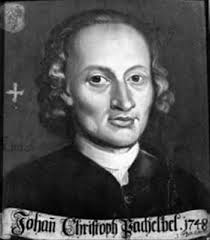

This Week in Classical Music: August 26, 2024. Performers and Conductors. Few composers were born this week; we’ll name two: Rebecca Clarke, a British composer and violist, born on August 27th of 1886, in Harrow, and Johan Pachelbel, the German composer, famous for his Cannon in D, but in reality, a prolific composer, whose Hexachordum Apollinis, a collection of keyboard music, deserves to be known better. He was born on September 1st of 1653 in Nuremberg.

August 27th of 1886, in Harrow, and Johan Pachelbel, the German composer, famous for his Cannon in D, but in reality, a prolific composer, whose Hexachordum Apollinis, a collection of keyboard music, deserves to be known better. He was born on September 1st of 1653 in Nuremberg.

If we turn to the performers and interpreters – instrumentalists, singers, and conductors – those are aplenty. Itzhak Perlman was born on August 31st of 1945 in Tel Aviv. Perlman is deservedly famous: from about the mid-1960s to the mid-1990s he was one of the greatest violinists to perform actively; he then narrowed his classical repertoire and branched out into klezmer and jazz, while also teaching and conducting. Some criticize his playing as too romantic, but we think that’s unfair: Perlman made hundreds of recordings, many excellent, some phenomenal. His Beethoven’s piano and violin sonatas and Brahm’s violin sonatas with Vladimir Ashkenazy are of the highest order. Here, for example, is the recording of Brahm’s Violin Sonata no. 1 made by Perlman and Ashkenazy in 1983.

famous: from about the mid-1960s to the mid-1990s he was one of the greatest violinists to perform actively; he then narrowed his classical repertoire and branched out into klezmer and jazz, while also teaching and conducting. Some criticize his playing as too romantic, but we think that’s unfair: Perlman made hundreds of recordings, many excellent, some phenomenal. His Beethoven’s piano and violin sonatas and Brahm’s violin sonatas with Vladimir Ashkenazy are of the highest order. Here, for example, is the recording of Brahm’s Violin Sonata no. 1 made by Perlman and Ashkenazy in 1983.

Three conductors were born this week, two Germans and one Hungarian who worked mostly in Germany. The native Germans are Wolfgang Sawallisch and Karl Böhm; the Hungarian is István Kertész. We’ve written about Böhm, one of the most important conductors of the 20th century but a deeply flawed personality, more than once, for example, here. Both Sawallisch and Kertész were born in the 1920s: Sawallisch in 1923, in Munich on August 26th, Kertész in 1929, in Budapest, on August 28th. Sawallisch took piano lessons as a child and continued his musical education at the Musikhochschule in Munich. As a young man, he fought in the German army during WWII and was captured by the British in Italy at the tail-end of it. At the age of 30 he conducted the Berlin Philharmonic, and at 34 became the youngest conductor to appear at Bayreuth, where he led the performance of Tristan und Isolde. In 1960, he became the principal conductor of the Vienna Symphony (not to be confused with the much more famous Vienna Philharmonic). For 20 years he was the music director of the Bavarian State Opera where he conducted 32 complete cycles of Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen. From 1993 to 2003 he was the music director of the Philadelphia Orchestra. He died in 2013, months shy of his 90th birthday.

István Kertész’s life was much shorter, he was only 43 when he drowned while swimming in the Mediterranean in Herzliya, a town next to Tel Aviv, in 1973. Kertész was Jewish, as were so many other Hungarian conductors: Fritz Reiner, Antal Doráti, Eugene Ormandy (born Jenő Blau), George Szell, Ferenc Fricsay (only his mother was Jewish but that was enough to be prosecuted in anti-Semitic Hungary), and Georg Solti. In 1944 most of Kertész’s relatives were deported to Auschwitz and killed there. Kertész survived, went to study at the Ferenc Liszt Academy when the war was over, and had some conducting assignments after graduation. He and his family left Hungary after the 1956 Uprising and settled in Germany. From 1958 to 1963 he was the music director of the Augsburg Opera, where he conducted a wide repertoire. At the same time, he guest-conducted many major European and American orchestras. In 1964, he assumed the same position with the Cologne Opera and also became the principal conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra. István Kertész had an unusually broad repertoire, both in opera and orchestral music. He conducted many major orchestras and was the first choice of the Cleveland musicians to replace the departing Geroge Szell (instead, Lorin Maazel was hired by the board).

Richard Tucker, a wonderful American tenor (also Jewish – we seem to have a Jewish theme today) was born on August 28th of 1913 in Brooklyn, NY. We’ll get back to him another time.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: August 19, 2024. Peri, Bernstein. Jacopo Peri, an Italian composer of the transitional period between the Renaissance and Baroque and author of the very first opera, Dafne, was born on August 20th of 1561. Last year we got involved with Peri, his contemporary Emilio de’ Cavalieri, and the process of transitioning from one, deeply established musical style to a very different one, a style that may be considered a “lesser” one, at least in its initial phase. We still find this process and the personalities involved very interesting. You may want to read about Peri and the period here, here, and here.

first opera, Dafne, was born on August 20th of 1561. Last year we got involved with Peri, his contemporary Emilio de’ Cavalieri, and the process of transitioning from one, deeply established musical style to a very different one, a style that may be considered a “lesser” one, at least in its initial phase. We still find this process and the personalities involved very interesting. You may want to read about Peri and the period here, here, and here.

Claude Debussy, one of the most influential composers of his time, was born in St. Germain-en-Laye on August 22nd of 1862. And when we say, “of his time,” we’re talking about one of the most fecund periods of classical music, the period from 1894, when Debussy composed Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune, till his death in 1918 at the age of 55. Just for reference, let’s take a look at who else was active during the period. Here’s what we see: Gustav Mahler, who, by the way, conducted the Prélude in New York in 1910, his whole output falls within this period; Sergei Rachmaninov, whose piano concertos no. 2 and no. 2?? were written in the first decade of the 20th century; much of Alexander Scriabin’s late works; Richard Strauss’s most important tone poems and operas such as Salome and Der Rosenkavalier, all fall within the period. Composers as different as Arnold Schoenberg, Ottorino Respighi, Manuel de Falla, and of course, Debussy’s younger contemporary and friend Maurice Ravel were all extremely productive during the same period. And still, Debussy’s star shines brightly. While his piano and orchestral works are probably among his most popular, he worked in many genres. Pelléas et Mélisande, premiered in 1902, is one of the most important operas of the 20th century. His chamber music is brilliant; he also wrote wonderful songs. We have quite a bit of Debussy’s music in our library, you may take a look here. A note on labeling: Debussy created a musical style, at some point called “Impressionism,” the label stuck; he hated the term, and so did Ravel, another “impressionist.”

Gustav Mahler, who, by the way, conducted the Prélude in New York in 1910, his whole output falls within this period; Sergei Rachmaninov, whose piano concertos no. 2 and no. 2?? were written in the first decade of the 20th century; much of Alexander Scriabin’s late works; Richard Strauss’s most important tone poems and operas such as Salome and Der Rosenkavalier, all fall within the period. Composers as different as Arnold Schoenberg, Ottorino Respighi, Manuel de Falla, and of course, Debussy’s younger contemporary and friend Maurice Ravel were all extremely productive during the same period. And still, Debussy’s star shines brightly. While his piano and orchestral works are probably among his most popular, he worked in many genres. Pelléas et Mélisande, premiered in 1902, is one of the most important operas of the 20th century. His chamber music is brilliant; he also wrote wonderful songs. We have quite a bit of Debussy’s music in our library, you may take a look here. A note on labeling: Debussy created a musical style, at some point called “Impressionism,” the label stuck; he hated the term, and so did Ravel, another “impressionist.”

It's said that Debussy influenced all composers of the 20th century except for Schoenberg. That is an exaggeration, but Debussy did influence many composers, from Stravinsky to Les Six and on. One composer also born this week who clearly wasn’t is Karlheinz Stockhausen. Some years ago we wrote: “In our library, we have three recordings of Karlheinz Stockhausen. Two of them are rated “one note,” the lowest rating that could be given. Considering that one piece is played by the pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard, we can safely assume that it’s not the performance that our listeners disliked but the pieces themselves. Stockhausen […] is considered one of the seminal composers of the second half of the 20th century. While we acknowledge the disapproval of some listeners, we think that his music is worth the effort, even if in small doses, and will continue bringing him up on occasion.” Since then, we added just one piece by Stockhausen, a composition called Kreuzspiel. It didn’t get rated, maybe nobody wanted to listen to it. The one-note ratings on older recordings still stand.

The great Leonard Bernstein was born on August 25th of 1918. Also, Lili Boulanger, whose life was tragically short, was born on August 21st of 1893; the Romanian composer and violinist George Enescu, born on August 19th of 1881; and a very interesting Austrian (and later American) composer Ernst Krenek, he was born on August 23rd of 1900. Permalink