Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

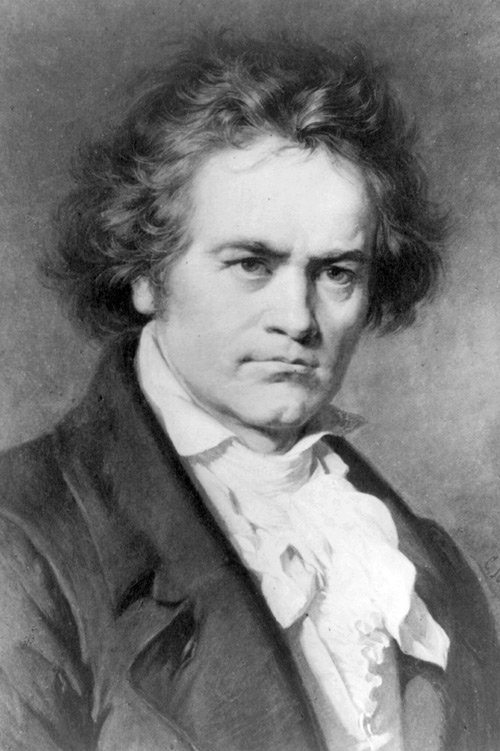

This Week in Classical Music: December 16, 2024. Beethoven and more. Today is the birthday of Ludwig van Beethoven, and it’s a relief to celebrate it this year: gone, or mostly gone is the insanity of 2020 when the gender and the color of a composer became the determinant of his (and especially her) value. In 2020 Beethoven became one of the white, male and mostly dead bunch, and for that, wasn’t considered to be worth much. We still remember the infamous “musicology” article titled “Beethoven was an above-average composer: let’s leave it that.” Fortunately, in 2020 Beethoven is back to being one of the greatest, occupying an enormous space in the musical culture of Europe and the world. One of his most profound compositions was the piano sonata no. 29, op. 106 nicknamed “Hammerklavier,” one of the greatest piano sonatas ever written. It was composed from the fall of 1817 through the first half of 1818, after a period when Beethoven’s output was unusually slim. Hammerklavier is unusually long, running about 40 to 45 minutes (the slow third movement alone takes from 15 to 25 minutes, depending on the performer – about 20 minutes in the version we’re about to hear), and was by far the longest piano piece written up to that time. Despite its length, it is intense from the beginning to the end, full of amazing musical ideas, and is never dull. As this sonata is one of the most important pieces in the piano repertoire, practically all great (and many not-so-great) pianists tackled it during their careers. Thus, we are left with many remarkable performances of which it’s impossible to select the “best” one (or even ten). Here is the great Soviet pianist Emil Gilels, in a 1983 recording (his contemporary and competitor Sviatoslav Richter’s interpretation is also excellent). And let’s make one thing clear: Florence Price, for all her obvious gifts, didn’t come even remotely close to creating something as profound and significant, all accolades from the woke musicologists and media aside.

is the insanity of 2020 when the gender and the color of a composer became the determinant of his (and especially her) value. In 2020 Beethoven became one of the white, male and mostly dead bunch, and for that, wasn’t considered to be worth much. We still remember the infamous “musicology” article titled “Beethoven was an above-average composer: let’s leave it that.” Fortunately, in 2020 Beethoven is back to being one of the greatest, occupying an enormous space in the musical culture of Europe and the world. One of his most profound compositions was the piano sonata no. 29, op. 106 nicknamed “Hammerklavier,” one of the greatest piano sonatas ever written. It was composed from the fall of 1817 through the first half of 1818, after a period when Beethoven’s output was unusually slim. Hammerklavier is unusually long, running about 40 to 45 minutes (the slow third movement alone takes from 15 to 25 minutes, depending on the performer – about 20 minutes in the version we’re about to hear), and was by far the longest piano piece written up to that time. Despite its length, it is intense from the beginning to the end, full of amazing musical ideas, and is never dull. As this sonata is one of the most important pieces in the piano repertoire, practically all great (and many not-so-great) pianists tackled it during their careers. Thus, we are left with many remarkable performances of which it’s impossible to select the “best” one (or even ten). Here is the great Soviet pianist Emil Gilels, in a 1983 recording (his contemporary and competitor Sviatoslav Richter’s interpretation is also excellent). And let’s make one thing clear: Florence Price, for all her obvious gifts, didn’t come even remotely close to creating something as profound and significant, all accolades from the woke musicologists and media aside.

We’ve been recently reminded by one of the listeners that we’ve never written about Rodion Shchedrin. What can we say? We admit to being prejudiced, and that’s the reason why we’ve never posted an entry about Shchedrin. His rendition of Bizet’s Carmen, which he created for his wife, the ballerina assoluta Maya Plisetskaya, is very good, though we still think that his main life achievement was to be married to her for 57 years (Plisetskaya was seven years his older). Shchedrin was born on this day 91 years ago in Moscow. He studied the piano and composition at the Moscow Conservatory. In 1973 he succeeded Shostakovich as the chairman of the Composers’ Union of the Russian Federation. He composed in many genres, from the opera (he wrote seven of them) to ballet music, symphonies, concertos for orchestra and individual instruments, vocal music and piano works. Much of it has been recorded and you can hear it on YouTube and streaming services.

Rosalyn Tureck, a great interpreter of the music of Back, was born 110 years ago, on December 14th of 1914 in Chicago. Ida Haendel, the wonderful violinist, was born on December 15th of 1928 in Chelm, Poland. She won the Warsaw Conservatory gold medal and the first Huberman Prize for playing Beethoven’s Violin Concerto at the age of five (yes, it’s not a typo; at nine she played the same concerto in London on her tour of the country). And Fritz Reiner, one of the greatest conductors of the 20th century, was born in Budapest on December 19th of 1888. He, and later another Hungarian Jewish conductor, Georg Solti, made the Chicago Symphony into one of the best orchestras in the world, something the orchestra board seems intent on dismantling.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: December 9, 2024. Three Francophone composers. One Belgian, Cesar Franck, and two French composers, Hector Berlioz, and Olivier Messiaen, were born this week. Berlioz, by far the greatest French composer of the mid-19th century, was born on December 11th of 1803 in the small town of La Côte-Saint-André in southeastern France. It seems strange, but France, artistically splendid, was not well represented in classical music in the first half of the 19th century; not, for example, as were the German-speaking countries. The 18th century was the time of Lully, Charpentier, Couperin and Rameau, the second half of the 19th century was also brimming with talent: from Gounod, Saint-Saëns and Bizet to Massenet and Fauré and then to Debussy and Ravel, well into the 20th century. Between those two groups, though, Berlioz was practically alone. He was unique, idiosyncratic, didn’t follow anybody, and didn’t leave a musical school after himself. All the same, he was a composer of genius. His Symphonie fantastique, composed in 1830, stands out in the originality of structure and musical ideas; the enormous opera, Les Troyens, is rarely performed but is exceptional in its richness. Harold en Italie, formally a symphony with the viola obbligato, is one of the best viola concertos ever composed. And of course, there are more: symphonic pieces, operas, choral works, like the Damnation of Faust, and songs. The Damnation of Faust runs for more than two hours, but here is a snippet: the first scene in which Faust contemplates nature. Kenneth Riegel is the tenor, Sir Georg Solti conducts the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in this 1982 recording.

born this week. Berlioz, by far the greatest French composer of the mid-19th century, was born on December 11th of 1803 in the small town of La Côte-Saint-André in southeastern France. It seems strange, but France, artistically splendid, was not well represented in classical music in the first half of the 19th century; not, for example, as were the German-speaking countries. The 18th century was the time of Lully, Charpentier, Couperin and Rameau, the second half of the 19th century was also brimming with talent: from Gounod, Saint-Saëns and Bizet to Massenet and Fauré and then to Debussy and Ravel, well into the 20th century. Between those two groups, though, Berlioz was practically alone. He was unique, idiosyncratic, didn’t follow anybody, and didn’t leave a musical school after himself. All the same, he was a composer of genius. His Symphonie fantastique, composed in 1830, stands out in the originality of structure and musical ideas; the enormous opera, Les Troyens, is rarely performed but is exceptional in its richness. Harold en Italie, formally a symphony with the viola obbligato, is one of the best viola concertos ever composed. And of course, there are more: symphonic pieces, operas, choral works, like the Damnation of Faust, and songs. The Damnation of Faust runs for more than two hours, but here is a snippet: the first scene in which Faust contemplates nature. Kenneth Riegel is the tenor, Sir Georg Solti conducts the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in this 1982 recording.

As much as Berlioz was the greatest French composer of the middle of the 19th century, Olivier Messiaen was, in our opinion, the greatest French composer of the middle of the 20th. Messiaen was born in Avignon on December 10th of 1908. He was admitted to the Paris Conservatory at eleven; among his teachers were Pail Dukas and Charles-Marie Widor, composer and organist. Messiaen loved this instrument. In 1931 he was appointed the organist of Église de la Sainte-Trinité, a church not far from Gare Saint-Lazare, and held this position for the rest of his life. In 1940, at the outbreak of World War II, Messiaen was drafted into the French army as a medical auxiliary (he had poor eyesight). He was captured by the Germans soon after, at Verdun, the site of the terrible battles of the previous world war, and sent to a camp. There he met a violinist, a cellist and a clarinetist. He wrote a trio for them, and eventually incorporated it into the Quartet for the End of Time, creating a part for himself on the piano. It was first performed in January 1941 in the camp for an audience of prisoners and prison guards. We’ll hear two movements from the Quartet: Movement I, Liturgie de cristal (here), and Movement II, Vocalise, pour l'Ange qui annonce la fin du temps (here). It’s performed by a quartet anchored by Daniel Barenboim on the piano.

As for Franck, we love his violin sonata. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: December 2, 2024. Barbirolli and more. We’ll start with a notable anniversary: the British conductor, Sir John Barbirolli was born on December 2nd of 1899, 125 years ago. Born in London, Barbirolli was of Italian-French descent. He started as a cellist, playing in small orchestras. During the Great War, he served for two years. Barbirolli started conducting, mostly in opera, in 1927. He also conducted several provincial orchestras, including the Hallé, later his favorite, which he built into a world-class ensemble. In 1936 he was invited to guest-conduct the New York Philharmonic; after one successful season, he was appointed the permanent conductor, in succession to Toscanini. His contract was renewed till 1942. That year, in the middle of WWII, he crossed the Atlantic several times to conduct several London orchestras as a gesture of support for Britain; these were dangerous undertakings considering the number of ships sunk by the German U-boats. In 1943 he returned to England to take charge of the Hallé orchestra in Manchester and stayed at the helm till 1967.

1899, 125 years ago. Born in London, Barbirolli was of Italian-French descent. He started as a cellist, playing in small orchestras. During the Great War, he served for two years. Barbirolli started conducting, mostly in opera, in 1927. He also conducted several provincial orchestras, including the Hallé, later his favorite, which he built into a world-class ensemble. In 1936 he was invited to guest-conduct the New York Philharmonic; after one successful season, he was appointed the permanent conductor, in succession to Toscanini. His contract was renewed till 1942. That year, in the middle of WWII, he crossed the Atlantic several times to conduct several London orchestras as a gesture of support for Britain; these were dangerous undertakings considering the number of ships sunk by the German U-boats. In 1943 he returned to England to take charge of the Hallé orchestra in Manchester and stayed at the helm till 1967.

Barbirolli was fond of English music, especially Elgar, Delius and Vaughan Williams (one of his most famous recordings is that of Elgar’s Cello Concerto with Jacqueline du Pré). Later he started conducting Mahler and Bruckner and was quite successful. Here’s the first movement of Bruckner’s Symphony no. 9. Sir John Barbirolli conducts the combined forces of the Hallé Orchestra and the BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra in a live recording from December 14, 1961. And for more enjoyment, here are the second and third movements.

December 2nd is also Maria Callas’s anniversary: she was born on that day in New York in 1923. Last year we celebrated La Divina’s 100th birthday, here.

Several composers have their anniversaries this week. Probably the most famous of them is Jean Sibelius, born on January 8th of 1865. Finland’s national hero, Sibelius was a highly original composer working within traditional musical idiom. He wrote seven symphonies, some more interesting than others, a violin concerto, one of the best ever, and many other pieces. We admit that Sibelius is not one of our favorites, which is probably the reason we never dedicated a full entry to him. Maybe next year.

Several more well-known names: Padre Antonio Soler, a Spanish (Catalan) composer, born on December 3rd of 1729, known for his short, one-movement clavier sonatas; Francesco Geminiani, an Italian composer and violinist, famous in his time and much less so in ours, born in Lucca on December 5th of 1687; Pietro Mascagni, another Italian, who wrote one masterpiece, the opera Cavalleria rusticana but not much else of real value, he was born in Livorno on December 7th of 1863; and Henryk Gorecki whose “sacred minimalist” pieces remain very popular with audiences worldwide. He was born on December 6th of 1933.

Finally, we’d like to mention Ernst Toch, one of the many Jewish composers from Germany and Austria, whose lives and careers were shattered by the Nazis. Toch was born in Leopoldstadt, a Jewish district of Vienna, on December 7th of 1887. You can read about him here and here. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: November 25, 2024. A Busy Week. This week is full of interesting anniversaries, but unfortunately, we’re distracted by other things to give the composers and musicians born this week the attention they deserve. Therefore, we’ll limit ourselves to a simple list. Jean-Baptiste Lully, an Italian who became the most important composer of the early French Baroque, was born in Florence on November 28th of 1632. He was a favorite of Louis XIV, the Sun King, and Molière’s friend.

and musicians born this week the attention they deserve. Therefore, we’ll limit ourselves to a simple list. Jean-Baptiste Lully, an Italian who became the most important composer of the early French Baroque, was born in Florence on November 28th of 1632. He was a favorite of Louis XIV, the Sun King, and Molière’s friend.

Anton Stamitz, a son of Johann Stamitz and a brother of Carl Stamitz, all prominent composers, was born in Německý Brod, Bohemia, on November 27th of 1750. The family lived in Mannheim, where the father was instrumental in making the court orchestra into one of the best ensembles in Europe. Anton played in this orchestra (he was a virtuoso violinist). Here is his Concerto for Two Flutes & Orchestra in G major; Shigenori Kudo and Jean-Pierre Rampal are the flutes; Josef Schneider conducts the Salzburg Mozarteum Orchestra.

The great Italian master of the bel canto opera, Gaetano Donizetti was born in Bergamo on November 29th of 1797. He wrote about 70 operas; among his best are Anna Bolena, L'elisir d'amore, Maria Stuarda and Lucia di Lammermoor. Maria Callas brought Anna and Lucia to life like very few have done, before or after.

Ferdinand Ries was a minor composer, Beethoven’s pupil, friend, secretary and copyist, and, importantly, the person who commissioned Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Like his teacher, Ries was born in Bonn, on November 28th of 1784.

Three Russian composers were also born this week, all in November: Anton Rubinstein, on the 28th, in 1829, Sergei Taneyev, on the 25th, in 1856, and Sergey Lyapunov, on the 30th, in 1859. Rubinstein was not just a composer but also a brilliant pianist, second only to Liszt, and conductor. In 1862 he founded the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, the first one in Russia (his brother, Nikolai Rubinstein, also a pianist, composer and conductor, founded the Moscow Conservatory in 1866). Taneyev was Nikolai Rubinstein’s pupil at the Moscow Conservatory and Tchaikovsky’s close friend (Tchaikovsky dedicated the symphonic poem Francesca da Rimini to Taneyev). Lyapunov wrote, among other things, Twelve Transcendental Etudes (études d'exécution transcendente). Here’s the second of these etudes, "The Ghosts' Dance," played by Florian Noack.

And speaking of etudes of transcendental difficulty, Charles-Valentin Alkan, a French virtuoso pianist and composer, wrote many of them (Alkan was born in Paris on November 30th of 1813). Marc-André Hamelin, one of the most technically capable pianists of our time, is one of the few who can give Alkan’s music its due. Alkan, a French Jew, had an unusual and interesting life and we’ll dedicate a separate entry to him. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: November 18, 2024. A Day Worth a Week. Here’s what happened on this day in classical music: In 1786, Carl Maria von Weber was born in Eutin, a small town not far from Lübeck. He’s famous as one of the first German Romantic composers, especially for his opera Der Freischütz. At his time, he was also known as a virtuoso pianist, conductor, and an important music critic, like E.T.A. Hoffmann around the same time and Robert Schumann a generation later. Here’s the Overture to Der Freischütz (The Freeshooter or The Marksman in English). Carlos Kleiber conducts the Staatskapelle Dresden.

small town not far from Lübeck. He’s famous as one of the first German Romantic composers, especially for his opera Der Freischütz. At his time, he was also known as a virtuoso pianist, conductor, and an important music critic, like E.T.A. Hoffmann around the same time and Robert Schumann a generation later. Here’s the Overture to Der Freischütz (The Freeshooter or The Marksman in English). Carlos Kleiber conducts the Staatskapelle Dresden.

Though not a musician himself, our next celebrated birthday is that of an essential part of the famous duo responsible for the best comic operas in English: the librettist and playwright William Schwenck (W.S.) Gilbert, in partnership with the composer Arthur Sullivan, created such comic masterpieces as H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance and The Mikado. Gilbert was born on this day in London in 1836. His partnership with Sullivan lasted 20 years and together they wrote 14 operas.

Ignacy Jan Paderewski¸ the Polish pianist, composer and statesman, was born on this day in a village of Kurilovka, then part of the Russian Empire, in 1860. Padarewski was one of the most famous pianists of his time, but during the Great War, he became a politician, joining the Polish National Committee in Paris: Poland, divided between Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Germany, didn’t exist as a state, and the National Committee pressed for the recognition of Poland once the war was over. Paderewski spoke to President Wilson, the Congress, and the leaders of France and the UK. More persuasive than any other Polish leader, he was instrumental in birthing Poland as a state. In January of 1919, he was appointed Prime Minister and the Minister of Foreign Affairs of this new state. In this capacity, he signed for Poland the Treaty of Versailles. He proved to be a poor administrator and resigned his premiership in December of 1919. He continued as the foreign minister till 1922 and then left politics for good, resuming his musical career. He returned to public life in 1939, after Germany (and then the Soviet Union) invaded Poland. He was made President of the Sejm (parliament) in exile in London. Paderewski died in New York in 1941.

Heinrich Schiff, a wonderful Austrian cellist, was also born on this day, in 1951. His performances of Bach’s unaccompanied cello pieces were peerless. All standard cello concertos were part of his repertoire; he also premiered several concertos of his contemporaries, like Henze and Richard Rodney Bennett. Schiff’s career was not very long: in 2010, when he was 60, he quit performing because of a consistent pain in his right shoulder. Schiff died in December of 2016.

And one more, and important, anniversary: the great conductor Eugene Ormandy was born on this day 125 years ago as Jenő Blau into a Jewish family in Budapest, then in Austria-Hungary. He started studying the violin at the age of three and entered the Royal National Hungarian Academy of Music when he was five, the youngest student ever. He emigrated to the US in 1921, and for the first several years played violin in small orchestras. He started conducting, sporadically, in 1927 and in 1931, almost by chance, led a Philadelphia Orchestra concert, substituting for Toscanini who fell ill. Following this successful performance, he was appointment the music director of the Minnesota Symphony. In 1936 he returned to Philadelphia to share the leadership of the orchestra with Stokowski, and two years later became their single music director, the position he held for the following 42 years, the longest tenure in any major US orchestra.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: November 11, 2024. Leonid Kogan. The Soviet Union was obsessed with rankings, which were applied (or assumed) in many areas. Within the power structures, there was of course, the one and only Secretary General of the Communist party; in city planning, Moscow was number one and treated differently than any other city. The same applied to the arts. There had to be a best ballerina (Ulanova first, then Plisetskaya), and even in music, the same rankings applied. After Stalin’s death, Shostakovich was officially considered the greatest living composer. There had to be pianist number one (Sviatoslav Richter), but also pianist number two (Emil Gilels), same for the violin or cello (Rostropovich as cellist number one, Daniil Shafran number two). The ranking among the violinists was this: David Oistrakh – number one, Leonid Kogan – number two. Oistrakh was, undisputable, a great violinist, but so was Kogan, and looking from the outside, these rankings look silly, but such was the nature of Sovietsociety, where fuzzy diversity – whether of ideas or tastes – was not welcome.

structures, there was of course, the one and only Secretary General of the Communist party; in city planning, Moscow was number one and treated differently than any other city. The same applied to the arts. There had to be a best ballerina (Ulanova first, then Plisetskaya), and even in music, the same rankings applied. After Stalin’s death, Shostakovich was officially considered the greatest living composer. There had to be pianist number one (Sviatoslav Richter), but also pianist number two (Emil Gilels), same for the violin or cello (Rostropovich as cellist number one, Daniil Shafran number two). The ranking among the violinists was this: David Oistrakh – number one, Leonid Kogan – number two. Oistrakh was, undisputable, a great violinist, but so was Kogan, and looking from the outside, these rankings look silly, but such was the nature of Sovietsociety, where fuzzy diversity – whether of ideas or tastes – was not welcome.

November 14th marks Leonid Kogan’s 100th anniversary. He was born into a Jewish family in Ekaterinoslav, now Dnepr, in Ukraine. He studied in Moscow, first in the Central Music school, then in the Conservatory, in both places with Abram Yampolsky, the great Russian violin teacher (Yampolsky was so taken by his talented pupil that, for a while, he housed him in his small apartment). Kogan’s virtuosity became obvious very early, but, unlike many young musicians, he also demonstrated deep insights into the music he played. At the age of 16 he played Brahm’s violin concerto, and at 20, while still a student at the conservatory, he was given the official position of a soloist at the Moscow Philharmonic Organization, the body responsible for managing the careers of professional musicians and organizing concerts not only in the capital but in many other cities of the country. With that, Kogan embarked on several tours of the Soviet Union. In 1947 he shared the first prize at the Prague youth competition, and in 1949 he played all of Paganini’s 24 Caprices in one evening. In 1951 he won the prestigious Queen Elisabeth competition in Brussels and in 1955 he was allowed to play concerts in Paris (at that time, only very few Soviet musicians were allowed to travel to Western Europe or the US, Sviatoslav Richter’s first tour, to the US, happened only in 1960). The Paris concerts were very successful, and Kogan, not well known in the West at the time since most of his recordings were made by the Soviet firm “Melodia” and unavailable outside the Iron Curtain, became famous. Other Western tours followed: South America in 1956, and then, in 1957-59, the tour of North America. As Howard Taubman wrote of his concert at Carnegie Hall, “He left no doubt of the exceptional subtlety and refinement of his art. If the men in the Kremlin will forgive the expression, Mr. Kogan played like an aristocrat.”

Kogan, who loved large-form pieces, also played chamber music. The Gilels-Kogan-Rostropovich trio performed for about 10 years and made numerous recordings. Kogan was married to Elizaveta Gilels, sister of pianist Emil Gilels and also a student of Abram Yampolsky. Kogan died of a heart attack on December 17th of 1982, age 58, just outside of Moscow while traveling by train to give a concert in a provincial city.

Brahm’s Violin concerto was one of Kogan’s favorites. He performed it often, with different orchestras, and many recordings are available, for example, two from 1967, one with the Moscow Philharmonic and another with the Philharmonia Orchestra of London, both conducted by Kirill Kondrashin. We like the one he made in 1959, even if its recording quality is not great. Again, Leonid Kogan plays with the Philharmonia Orchestra and again Kirill Kondrashin is conducting (here). Permalink