Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

September 9, 2019. Rome, by all means, Rome. Again, we’ll miss a week of great anniversaries. Henry Purcell was born 360 years ago; also this week his compatriot, William Boyce, was born. It’s also Arnold Schoenberg’s 145th birthday. The great Italian composer Girolamo Frescobaldi, originally from Ferrara but very successful in Rome (he was appointed the organist of the St. Peter’s basilica) was also born this week. And so were Arvo Pärt and the pianist great Maria Yudina.

September 2, 2019. Ferrara. While in this musical city, once second only to Rome, we’ll miss the anniversaries of a whole group of composers, from Anton Bruckner and Johann Christian Bach to Antonin Dvořák and Darius Milhaud. We’ll have a chance to commemorate them another time.

August 26, 2019. Pachelbel and Böhm. Johann Pachelbel was born on September 1st of 1653 in Nuremberg. These days he’s known mostly for his Cannon in D, which is unfair and unfortunate, as Pachelbel was an interesting composer working in many different genres. In one of our previous posts we referred to one of his most important clavier pieces, Hexachordum Apollinis ("Six Strings of Apollo"). “… a set of six arias followed by variations, which, according to Pachelbel himself, could be performed either on the organ or the harpsichord. Variations were a somewhat new musical form in the 17th century, and Hexachordum was by far the most interesting set of variations written to date.” Hexachordum was published in 1699 while Pachelbel was again living in Nuremberg where he moved from Erfurt (in Erfurt he became good friends with Ambrosius Bach, Johann Sebastian’s father; Ambrosius even asked Pachelbel to be the godfather to his daughter Johanna Juditha. Pachelbel also taught music to his son Johann Christoph, who in turn became a music teacher of his younger brother, Johann Sebastian). In Nuremberg Pachelbel was the organist at St. Sebaldus Church, the most important church in the city. He held this position till his death in March of 1706. Pachelbel is noted mostly for his organ works, but he was a wonderful composer of vocal church music as well. Here, for example, is one of his two settings of Magnificat (this one is in D Major). It’s performed by the ensemble Cantus Cölln under the direction of Konrad Junghänel. And speaking of the Magnificat, Pachelbel wrote 60 so called Magnificat Fugues – we’ll talk about them another time.

previous posts we referred to one of his most important clavier pieces, Hexachordum Apollinis ("Six Strings of Apollo"). “… a set of six arias followed by variations, which, according to Pachelbel himself, could be performed either on the organ or the harpsichord. Variations were a somewhat new musical form in the 17th century, and Hexachordum was by far the most interesting set of variations written to date.” Hexachordum was published in 1699 while Pachelbel was again living in Nuremberg where he moved from Erfurt (in Erfurt he became good friends with Ambrosius Bach, Johann Sebastian’s father; Ambrosius even asked Pachelbel to be the godfather to his daughter Johanna Juditha. Pachelbel also taught music to his son Johann Christoph, who in turn became a music teacher of his younger brother, Johann Sebastian). In Nuremberg Pachelbel was the organist at St. Sebaldus Church, the most important church in the city. He held this position till his death in March of 1706. Pachelbel is noted mostly for his organ works, but he was a wonderful composer of vocal church music as well. Here, for example, is one of his two settings of Magnificat (this one is in D Major). It’s performed by the ensemble Cantus Cölln under the direction of Konrad Junghänel. And speaking of the Magnificat, Pachelbel wrote 60 so called Magnificat Fugues – we’ll talk about them another time.

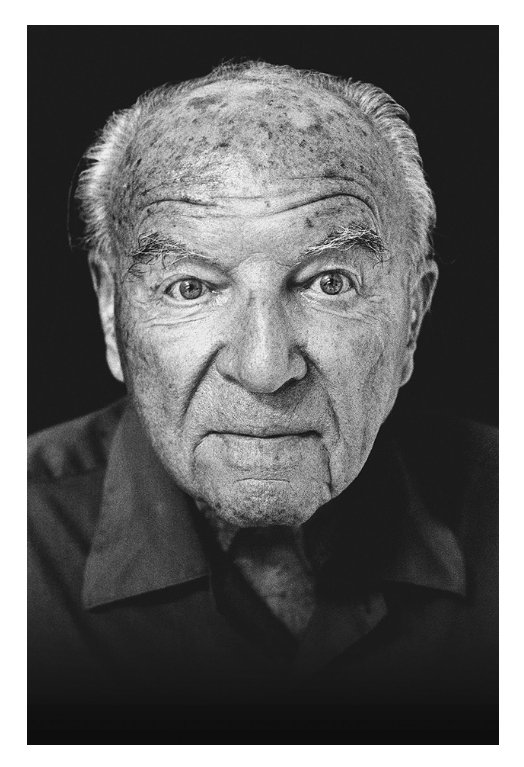

Karl Böhm, one of Austria’s most interesting but controversial conductors, was born on August 28th of 1894 in Graz. He made his conducting debut in 1917 in his hometown; in 1921 Bruno Walter invited him to the Staatsoper in Munich. He stayed there for six years; in 1927 he was invited to lead the opera in Darmstadt. There he performed several modern operas, including Berg’s Wozzeck. After serving in Hamburg he was invited to the Vienna Philharmonic. His 1933 staging of Tristan und Isolde was a huge success. While continuing his engagement in Vienna, one year later Böhm was made the music director of the Dresden Staatsoper. There he replaced Fritz Busch, who was forced to resign by the Nazis. Böhm’s career flourished under the Nazis, even though he never formally joined the Nazi party. He was the director of the Vienna Staatsoper during the last two years of WWII and then led it after the war, when the house was rebuilt. He also had a very successful international career, performing in all major houses of Europe and the US. Böhm made his debut at the Metropolitan Opera in 1957 with Don Giovanni and went on to conduct 262 performances. In 1966, Harold C. Schonberg, The New York Times’s chief music critic, wrote: ''Among the present group of Metropolitan Opera conductors, he towers like a colossus.” Böhm died in Salzburg on August 14th of 1981. He was 87.

Böhm was an enthusiastic and early supporter of the Nazi regime. According to Norman Lebrecht, in 1938 Böhm told the Vienna Philharmonic musicians that anyone who did not vote for Hitler’s Anschluss could not be considered a proper German. He advanced his career as Jewish and German musicians with Jewish ties were forced to leave. In 2015 the Salzburg Festival, itself accused of past anti-Semitism, affixed a plaque in its Karl-Böhm-Saal which states "Böhm was a beneficiary of the Third Reich and used its system to advance his career. His ascent was facilitated by the expulsion of Jewish and politically out-of-favor colleagues.”Permalink

August 19, 2019. Going for the unpopular. Claude Debussy was born this week, on August 22nd of 1782. We love Debussy and he remains one of the most popular composers, both among listeners and performers (in our library we have more than 230 recordings of his works, some pieces are played over and over again). While our listeners have many ways to celebrate Debussy, we will turn to the interesting, but not very popular, composers of the 20th century. Ernst Krenek (pronounced Krzhenek; like Dvorak, pronounced Dvorzhak), Krenek was Czech by birth, and his name originally was spelled Křenek. (The second letter, pronounced Rzh, was replaced with “R” when Krenek moved to the United States). Krenek was born in Vienna, son of a Czech soldier. He studied with the then-famous composer Franz Schreker. During the Great War he was drafted into the Austrian army but spent most of the time in Vienna, continuing his studies. In 1920 he followed Schreker to Berlin where he was introduced to many musicians; there he met Alma Mahler and her daughter Anna (by the time they met, Alma had already divorced her second husband, the architect Walter Gropius and was living with the poet Franz Werfel; Krenek fell in love with Anna and married her in 1924, though their marriage fell apart a few months later). The time in Berlin was very productive: Krenek wrote 18 large-scale pieces between 1921 and 1924. He also worked on parts of Gustav Mahler’s unfinished 10th Symphony but dropped the project as he felt that most of it was too under-developed. In 1925 Krenek traveled to Paris where he met the composers of Les Six; under their influence he decided that his music should be more accessible and wrote a “jazz-opera” Jonny spielt auf(Jonny Plays), which became very popular. Krenek followed with three more one-act operas, one of them, Der Diktator, based on the life of Mussolini. In 1928 Krenek returned to Vienna and became friends with Berg and Webern. He got interested in the 12-tone technique, a form of serialism which attempts to give each of the 12 notes of the scale equal weight. In 1933 he wrote an opera. Karl V, using this technique. It’s premier in Vienna was cancelled (the politics of art, following politics in general at the time, were turning toward things simple and nationalistic) but it was staged in Prague in 1938. Needless to say, it never gained the popularity of Jonny spielt auf. The Nazis labeled Krenek’s music “radical,” things were getting difficult in Austria as well, and soon after the Anschluss Krenek emigrated to the US. He taught in several conservatories and universities and eventually settled in Los Angeles (he moved to Chicago in 1949 to teach at the Chicago Musical College but returned to the West Coast because of the cold winters – and who would blame him). He taught at Darmstadt in early 1950 (Boulez and Stockhausen were among the attendees), continued composing using the serial technique and experimented with electronic music. His last piece was written when Krenek was 88. He died in Palm Springs on December 22nd of 1991. Here’s Krenek’s Piano Sonata no. 2 op. 59 written in 1928. It’s performed by the Russian pianist Maria Yudina. This 1972 recording is unique, as back then “modernist” music wasn’t approved in the Soviet Union. Yudina plays not only Krenek but also Alban Berg’s First piano sonata, the rarely performed “Things in themselves” by Sergei Prokofiev and four pieces by André Jolivet.

listeners and performers (in our library we have more than 230 recordings of his works, some pieces are played over and over again). While our listeners have many ways to celebrate Debussy, we will turn to the interesting, but not very popular, composers of the 20th century. Ernst Krenek (pronounced Krzhenek; like Dvorak, pronounced Dvorzhak), Krenek was Czech by birth, and his name originally was spelled Křenek. (The second letter, pronounced Rzh, was replaced with “R” when Krenek moved to the United States). Krenek was born in Vienna, son of a Czech soldier. He studied with the then-famous composer Franz Schreker. During the Great War he was drafted into the Austrian army but spent most of the time in Vienna, continuing his studies. In 1920 he followed Schreker to Berlin where he was introduced to many musicians; there he met Alma Mahler and her daughter Anna (by the time they met, Alma had already divorced her second husband, the architect Walter Gropius and was living with the poet Franz Werfel; Krenek fell in love with Anna and married her in 1924, though their marriage fell apart a few months later). The time in Berlin was very productive: Krenek wrote 18 large-scale pieces between 1921 and 1924. He also worked on parts of Gustav Mahler’s unfinished 10th Symphony but dropped the project as he felt that most of it was too under-developed. In 1925 Krenek traveled to Paris where he met the composers of Les Six; under their influence he decided that his music should be more accessible and wrote a “jazz-opera” Jonny spielt auf(Jonny Plays), which became very popular. Krenek followed with three more one-act operas, one of them, Der Diktator, based on the life of Mussolini. In 1928 Krenek returned to Vienna and became friends with Berg and Webern. He got interested in the 12-tone technique, a form of serialism which attempts to give each of the 12 notes of the scale equal weight. In 1933 he wrote an opera. Karl V, using this technique. It’s premier in Vienna was cancelled (the politics of art, following politics in general at the time, were turning toward things simple and nationalistic) but it was staged in Prague in 1938. Needless to say, it never gained the popularity of Jonny spielt auf. The Nazis labeled Krenek’s music “radical,” things were getting difficult in Austria as well, and soon after the Anschluss Krenek emigrated to the US. He taught in several conservatories and universities and eventually settled in Los Angeles (he moved to Chicago in 1949 to teach at the Chicago Musical College but returned to the West Coast because of the cold winters – and who would blame him). He taught at Darmstadt in early 1950 (Boulez and Stockhausen were among the attendees), continued composing using the serial technique and experimented with electronic music. His last piece was written when Krenek was 88. He died in Palm Springs on December 22nd of 1991. Here’s Krenek’s Piano Sonata no. 2 op. 59 written in 1928. It’s performed by the Russian pianist Maria Yudina. This 1972 recording is unique, as back then “modernist” music wasn’t approved in the Soviet Union. Yudina plays not only Krenek but also Alban Berg’s First piano sonata, the rarely performed “Things in themselves” by Sergei Prokofiev and four pieces by André Jolivet.

In our library, we have three recordings of Karlheinz Stockhausen. Two of them are rated one note, the lowest rating that could be given. Considering that one piece is played by the pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard, we can safely assume that it’s not the performance that our listeners disliked but the pieces themselves. Stockhausen was born on August 22nd of 1928 and is considered one of the seminal composers of the second half of the 20th century. While we acknowledge the disapproval of some listeners, we think that his music is worth the effort, even if in small doses, and will continue bringing him up on occasion.Permalink

August 12, 2019. From the 17th century to the 20th. This week we’ll commemorate three 17th century composers, Biber, Porpora and Greene, but will skip the ones born in the 18th (Salieri), 19th (Godard and Pierne) and the 20th (Ibert and Foss) centuries. Heinrich Ignaz Biber is the oldest of the three, he was born on August 12th of 1644, 375 years ago. On the musical timeline this places Biber between Dietrich Buxtehude and Johann Pachelbel (or, going outside of Germany, between Jean-Baptiste Lully and Arcangelo Corelli). Germany wasn’t as musically developed as, for example, Italy, so the period during which Biber was active (he died on May 3rd of 1704) may be considered Early to Middle Baroque. Biber was a violin virtuoso (you can read more about Biber here), and his main opus was The Rosary Sonatas, a set of 15 sonatas for violin and continuo, which are usually played on a harpsichord or an organ; (sometimes the violin is accompanied by a small string ensemble). The final piece of the cycle, Passacaglia, is for the violin solo. The sonata cycle is also known as Mystery Sonatas – we don’t know the real name of it, as the title page of the only manuscript copy, kept in the Bavarian State Library, has been lost. The Rosary Sonatas were completed somewhere around 1676 but were first published only in 1905. The sonatas are organized into three cycles, following the standard Catholic “15 Mysteries of the Rosary”: five Joyful Mysteries, five Sorrowful Mysteries and five Glorious Mysteries. In the manuscript, each sonata is preceded by the appropriate engraving. The first cycle (The Joyful Mysteries) starts with the Annunciation (Sonata 1), following by the Visitation, the Nativity, the Presentation of the Infant Jesus in the Temple and ends with The Finding in the Temple (“After three days they found him in the temple”). Here’s Sonata 2, The Visitation, performed by the ensemble Musica Antiqua Koln under the direction of Renhard Goebel.

19th (Godard and Pierne) and the 20th (Ibert and Foss) centuries. Heinrich Ignaz Biber is the oldest of the three, he was born on August 12th of 1644, 375 years ago. On the musical timeline this places Biber between Dietrich Buxtehude and Johann Pachelbel (or, going outside of Germany, between Jean-Baptiste Lully and Arcangelo Corelli). Germany wasn’t as musically developed as, for example, Italy, so the period during which Biber was active (he died on May 3rd of 1704) may be considered Early to Middle Baroque. Biber was a violin virtuoso (you can read more about Biber here), and his main opus was The Rosary Sonatas, a set of 15 sonatas for violin and continuo, which are usually played on a harpsichord or an organ; (sometimes the violin is accompanied by a small string ensemble). The final piece of the cycle, Passacaglia, is for the violin solo. The sonata cycle is also known as Mystery Sonatas – we don’t know the real name of it, as the title page of the only manuscript copy, kept in the Bavarian State Library, has been lost. The Rosary Sonatas were completed somewhere around 1676 but were first published only in 1905. The sonatas are organized into three cycles, following the standard Catholic “15 Mysteries of the Rosary”: five Joyful Mysteries, five Sorrowful Mysteries and five Glorious Mysteries. In the manuscript, each sonata is preceded by the appropriate engraving. The first cycle (The Joyful Mysteries) starts with the Annunciation (Sonata 1), following by the Visitation, the Nativity, the Presentation of the Infant Jesus in the Temple and ends with The Finding in the Temple (“After three days they found him in the temple”). Here’s Sonata 2, The Visitation, performed by the ensemble Musica Antiqua Koln under the direction of Renhard Goebel.

Nicola Porpora was 42 years younger than Biber (he was born on August 16th of 1686, one year after Bach and Handel) and lived in a very different world than the provincial Biber: born in Naples, he traveled around Europe, was accepted at the courts of the greatest monarchs and competed with non other than George Frideric Handel. In 1729 Porpora was invited to London by a group of nobles who wanted to set up an opera company to compete with Handel’s Royal Academy of Music. Porpora was appointed the music director of “The Opera of the Nobility”; he hired Senesino, the great contralto castrato, formerly Handel’s favorite who had fallen out with the composer and quit the Academy. Later Porpora hired the even more famous Farinelli. Unfortunately, none of this could save the company: it declared bankruptcy after the 1733-34 season; Porpora stayed in London for three more years working for other opera houses and then returned to Italy. Porpora is famous as an opera composer and also as a music teacher: among his students were Farinelli and Franz Joseph Haydn. Here’s an aria Alto Giove from Porpora’s opera Polifemo. It was premiered in London on February 1st of 1735 in King's Theatre, Haymarket. The countertenor Philippe Jaroussky is accompanied by the Australian Brandenburg Orchestra under the direction of Paul Dyer.

The English composer and organist Maurice Greene was born on August 12th of 1696. Here’s his famous setting of Psalm 39, Lord, let me know mine end. It’s performed by the Choir of Christ Church Cathedral with Stephen Farr on the organ.Permalink

August 5, 2019. More on the Music in Ferrara. Today we’ll continue exploring the music at the court of the dukes of Ferrara at the end of the 16th century and its famous ensemble, Concerto delle donne. Last week we mentioned the name of Laura Peverara, the lead singer, and said that it doesn’t tell us much. Turns out that with very little effort one can find a lot about this fascinating musician. Laura Peverara (her last name is sometimes spelled “Peperara”) was born in Mantua in the summer of 1563. Her mother, Margherita Costanzi, was a lady-in-waiting to Margherita Paleologa, the wife of Federico II, Duke of Mantua. Her father, Vincenzo Peveraro, was a scholar at the service of the Gonzaga family. Laura received a good education in Latin and music, probably studying with the children of Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga, a big patron of arts and composer himself. Giaches de Wert was then the maestro di cappella in Mantua, so it’s likely that he heard the young Laura singing and maybe even taught her. Laura was also known as an exceptional harp player. It’s clear that by 1580 Peverara was already famous: the poet Muzio Manfredi dedicated a sonnet to her. Later that year a remarkable collection of sonnets and madrigals was dedicated to her; among the composers who wrote the music for this collection were such luminaries as Orlando di Lasso, Luca Marenzio, Claudio Merulo and Giovanni Gabrieli (in one of the sonnets Laura is praised as “the second, after Virgil, most famous citizen of Mantua”). Alfonoso II, Duke of Ferrara, visited Mantua in 1580 and, taken by Laura’s beauty and singing, asked his wife (!), Margherita Gonzaga to write to her father, Guglielmo Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua, asking for his permission to hire Laura Peverara. The permission was given, and Laura, accompanied by her father, moved to Ferrara, to the consternation of the ladies of the court. In Ferrara, she found success immediately: Giovanni Battista Guarini, a poet and father of Anna Guarini, who would later join Peverara in Concerto delle donne, wrote a sonnet in which he praised her singing. Duke Alfonso had wanted to have an ensemble of female singers since he heard Tarquinia Molza, the famous singer and composer, in Modena in 1568. He already had two fine amateur singers,noblewomen Lucrezia Bendidio (the lover of the poet Torquato Tasso and then, later, of Cardinal Luigi d'Este) and her sister Isabella; with the addition of Laura Peverara and Anna Guarini, who was trained by Luzzasco Luzzaschi, the duke had a talented vocal group. Alfonso also hired Giulio Cesare Brancaccio, a soldier, adventurer and a fine bass. More singers joined the Concerto later. Luzzaschi usually accompanied the singers on the clavicembalo, a light, 16th century Italian version of the harpsichord. Laura played the harp while Brancaccio – the lute.

delle donne. Last week we mentioned the name of Laura Peverara, the lead singer, and said that it doesn’t tell us much. Turns out that with very little effort one can find a lot about this fascinating musician. Laura Peverara (her last name is sometimes spelled “Peperara”) was born in Mantua in the summer of 1563. Her mother, Margherita Costanzi, was a lady-in-waiting to Margherita Paleologa, the wife of Federico II, Duke of Mantua. Her father, Vincenzo Peveraro, was a scholar at the service of the Gonzaga family. Laura received a good education in Latin and music, probably studying with the children of Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga, a big patron of arts and composer himself. Giaches de Wert was then the maestro di cappella in Mantua, so it’s likely that he heard the young Laura singing and maybe even taught her. Laura was also known as an exceptional harp player. It’s clear that by 1580 Peverara was already famous: the poet Muzio Manfredi dedicated a sonnet to her. Later that year a remarkable collection of sonnets and madrigals was dedicated to her; among the composers who wrote the music for this collection were such luminaries as Orlando di Lasso, Luca Marenzio, Claudio Merulo and Giovanni Gabrieli (in one of the sonnets Laura is praised as “the second, after Virgil, most famous citizen of Mantua”). Alfonoso II, Duke of Ferrara, visited Mantua in 1580 and, taken by Laura’s beauty and singing, asked his wife (!), Margherita Gonzaga to write to her father, Guglielmo Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua, asking for his permission to hire Laura Peverara. The permission was given, and Laura, accompanied by her father, moved to Ferrara, to the consternation of the ladies of the court. In Ferrara, she found success immediately: Giovanni Battista Guarini, a poet and father of Anna Guarini, who would later join Peverara in Concerto delle donne, wrote a sonnet in which he praised her singing. Duke Alfonso had wanted to have an ensemble of female singers since he heard Tarquinia Molza, the famous singer and composer, in Modena in 1568. He already had two fine amateur singers,noblewomen Lucrezia Bendidio (the lover of the poet Torquato Tasso and then, later, of Cardinal Luigi d'Este) and her sister Isabella; with the addition of Laura Peverara and Anna Guarini, who was trained by Luzzasco Luzzaschi, the duke had a talented vocal group. Alfonso also hired Giulio Cesare Brancaccio, a soldier, adventurer and a fine bass. More singers joined the Concerto later. Luzzaschi usually accompanied the singers on the clavicembalo, a light, 16th century Italian version of the harpsichord. Laura played the harp while Brancaccio – the lute.

As we mentioned last week, Concerto delle donne was disbanded in 1597, after the death of Duke Alfonso II. Laura Peverara didn’t outlive the ensemble by long: she died in 1600 at the age of 37. Here’s a madrigal Misera, Che Faro by Giaches De Wert, one of the composers that thrived in Ferrara. It’s performed by the Consort of Musicke. We can think of Dame Emma Kirkby, the lead singer of the Concort, as performing the part Laura Peverara would’ve sung almost 450 years ago.Permalink