Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

December 11, 2017. Beethoven. Whatever deity was distributing musical birthdays throughout the year did a very poor job. There are meager weeks, and then there are periods like this one, in the middle of December: we’ve already missed the anniversaries of Jean Sibelius, Cesar Franck and Olivier Messiaen, all born during the last several days (and these are the foremost composers, there are more), while this week three more big ones are coming: that of Hector Berlioz, who was born on December 11th of 1803, Elliott Carter, the American modernist, born on the same day in 1908, and the talented Hungarian composer ZóltanKodaly, whose birthday is December 16th of 1882. We’ll skip all of them until a later date. All of it because December 16th is the birthday of Ludwig van Beethoven and that we cannot miss. Some years ago, we started a survey of Beethoven’s life through his music, pretty much arbitrarily picking his piano sonatas and symphonies, even though we may have as well followed the development of his genius though his quartets or piano trios – and we still might. For the time being, though, we’ll return to his piano sonatas. The last one we disucssed was the Sonata no. 7, op. 10, no. 3, written in 1798, when Beethoven was 27 years old. The next sonata, the famous no. 8, op. 13, known as Pathétique, was written the same year (the title Pathétique was given by the publisher, not the composer himself, but Beethoven liked it and that’s what the sonata was called ever since). Up to then, Beethoven was better known as a pianist rather than a composer (Václav Tomášek, a Czech composer and music teacher, who also heard Mozart, the supreme virtuoso of his time, play, considered Beethoven the greatest performer of all time). Beethoven’s predecessors, Haydn and Mozart, each wrote many wonderful piano sonatas, but Beethoven’s no. 8 was clearly different. Even though written in a traditional classical sonata form and clearly inspired by Mozart’s great piano sonata K. 457, Beethoven’s use of the themes and dynamics, the juxtaposition of different sections, his sense of the dramatic were all absolutely original, and recognizably Beethovenian. The sonata was dedicated to Beethoven’s friend and benefactor Prince Karl von Lichnowsky, who some years earlier played the same role for Mozart. It became immediately popular, establishing Beethoven as a leading composer. Here it is, in a 1959 recording made by the great Soviet pianist Sviatoslav Richter.

more), while this week three more big ones are coming: that of Hector Berlioz, who was born on December 11th of 1803, Elliott Carter, the American modernist, born on the same day in 1908, and the talented Hungarian composer ZóltanKodaly, whose birthday is December 16th of 1882. We’ll skip all of them until a later date. All of it because December 16th is the birthday of Ludwig van Beethoven and that we cannot miss. Some years ago, we started a survey of Beethoven’s life through his music, pretty much arbitrarily picking his piano sonatas and symphonies, even though we may have as well followed the development of his genius though his quartets or piano trios – and we still might. For the time being, though, we’ll return to his piano sonatas. The last one we disucssed was the Sonata no. 7, op. 10, no. 3, written in 1798, when Beethoven was 27 years old. The next sonata, the famous no. 8, op. 13, known as Pathétique, was written the same year (the title Pathétique was given by the publisher, not the composer himself, but Beethoven liked it and that’s what the sonata was called ever since). Up to then, Beethoven was better known as a pianist rather than a composer (Václav Tomášek, a Czech composer and music teacher, who also heard Mozart, the supreme virtuoso of his time, play, considered Beethoven the greatest performer of all time). Beethoven’s predecessors, Haydn and Mozart, each wrote many wonderful piano sonatas, but Beethoven’s no. 8 was clearly different. Even though written in a traditional classical sonata form and clearly inspired by Mozart’s great piano sonata K. 457, Beethoven’s use of the themes and dynamics, the juxtaposition of different sections, his sense of the dramatic were all absolutely original, and recognizably Beethovenian. The sonata was dedicated to Beethoven’s friend and benefactor Prince Karl von Lichnowsky, who some years earlier played the same role for Mozart. It became immediately popular, establishing Beethoven as a leading composer. Here it is, in a 1959 recording made by the great Soviet pianist Sviatoslav Richter.

The next sonata, no. 9 op. 14, no. 1, was written in the same 1798. The description often attached to this sonata is “modest.” And indeed, it doesn’t have the dramatic developments of its predecessor, it’s themes are not as expansive. Still, it’s recognizably Beethoven, couldn’t be mistaken for anything else. In 1801 Beethoven arranged the sonata for a quartet. It doesn’t have a number, 34, from the Hess catalogue. We’ll hear the original piano version here: the pianist Richard Goode is performing Beethoven’s Sonata no. 9 in E Major.

The second composition in op. 14, also written in 1798, is Sonata no. 10. Like the previous sonata, it’s dedicated to Baroness Josefa von Braun, at the time one of Beethoven’s patrons (her husband, Baron Peter von Braun, an industrialist, managed the Viennese court theaters). This sonata, like the no. 9, is not very ambitious, it could rather be called lyrical and exquisite – descriptions not often applied to Beethoven’s sonatas. Also, one can hear Haydn, still an influence. Here it is performed by the American pianist Stephen Kovacevich.Permalink

December 4, 2017. Three opera composers. The last couple of weeks we’ve dedicated our entries to single composers, first Penderecki and then Hindemith. In doing so, we missed several notable anniversaries, so we’ll try to catch up with them this week. Jean-Baptiste Lully, a miller’s son, was born on November 28th of 1632 in Florence. He was 14 when chevalier de Guise, who was visiting Italy at the time, noticed him there during Mardi Gras and brought him to France – not for his musical talents, but so that his niece, la Grande Mademoiselle, could talk to somebody in Italian. From these unusual beginnings, Lully developed into one of the greatest French composers of all time and the founder of the French opera. We’ve written about him extensively (for example, here or here), so we’ll just play some of his music. Lully composed Persée on the libretto of his frequent collaborator, Philippe Quinault. in 1682. Lully called Persée “tragédie lyrique” – opera genre he invented about 10 years earlier. We’ll hear the short Ouverture here (Christophe Rousset conducts the ensemble Les Talens Lyriques) and an excerpt from Act II (here). Cyril Auvity is Persée. Marie Lenormand – Andromède in an Opera Atelier production.

to France – not for his musical talents, but so that his niece, la Grande Mademoiselle, could talk to somebody in Italian. From these unusual beginnings, Lully developed into one of the greatest French composers of all time and the founder of the French opera. We’ve written about him extensively (for example, here or here), so we’ll just play some of his music. Lully composed Persée on the libretto of his frequent collaborator, Philippe Quinault. in 1682. Lully called Persée “tragédie lyrique” – opera genre he invented about 10 years earlier. We’ll hear the short Ouverture here (Christophe Rousset conducts the ensemble Les Talens Lyriques) and an excerpt from Act II (here). Cyril Auvity is Persée. Marie Lenormand – Andromède in an Opera Atelier production.

Lully wasn’t the only opera composer born around this time: two more Italians were, and they were “real” Italians, as Lully took French citizenship in 1661. Gaetano Donizetti’s birthday is November 29th of 1797. Donizetti came from the city of Bergamo, its beautiful older section called Upper City, Città Alta, famous for its architecture and musical tradition. Donizetti, together with Rossini and the younger Bellini, was one of the master composers of bel canto. Donizetti, who lived just 50 years (he died insane of syphilis), wrote almost 70 operas, but only few of them belong to the standard repertory these days: his masterpiece, Lucia di Lammermoor, Anna Bolena, L'elisir d'amore, Roberto Devereux, Maria Stuarta, and two comic operas, L'elisir d'amore and Don Pasquale. Here’s the Judgement Scene, the finale of Act I from Anna Bolena. Maria Callas, the tenor Gianni Raimoni and the bass Nicola Rossi-Lemeni in an exceptional live recording made exactly 60 years ago, in 1957 in La Scala. Gianandrea Gavazzeni is conducting the La Scala orchestra.

Another opera composer is Pietro Mascagni, who was born on December 7th of 1863. Mascagni wrote 15 operas, but is famous for just one, his very first, the marvelous Cavalleria Rusticana. If Donizetti was one of the creators of the Bel canto style, Mascagni, together with another one-opera marvel, Ruggero Leoncavallo, created the style called verismo, an Italian term that could be translated as realism, or maybe naturalism: the subjects of the verismo operas are down to earth, unheroic, like seamstresses and poets in Puccini’s La Boheme. Cavalleria Rusticana was premiered in 1890 (it’s interesting that Verdi was still to complete his last opera, Falstaff). There are more recordings of Cavalleria than practically of any other opera. There are even recordings conducted by Mascagni himself (hard to imagine, but Mascagni died on August 2nd of 1945; by then, Schoenberg was evolving his 12-tone system; Stravinsky was past his neo-classical period, and Olivier Messiaen had just written Vingt regards sur l'enfant-Jésus). Cavalleria is full of wonderful music; one of the best-known arias is Mamma, quel vino è generoso. Here it is in the 1957 recording by Franco Corelli. Arturo Basile conducts Orchestra Sinfonica di Torino della RAI.

We’ve written about three composers, but there are several more we’d like to note. Among them: Padre Antonio Soler, Jean Sibelius, Bohuslav Martinu, Joaquin Turina, a very interesting Soviet composer of Polish-Jewish descent, Mieczysław (or Moisey, as he was called in the Soviet Union) Weinberg, and Cesar Franck. We’ll write about them later.Permalink

November 27, 2017. Esther Walker on Paul Hindemith. A couple of weeks ago we missed Hindemith’s birthday: the German composer was born on November 16th of 1895. Most music lovers w can acknowledge his talent but many would also admit that Hindemith is not “their” composer, that he’s too distant, dry, cerebral. That’s what the Swiss pianist Esther Walker thought of Hindemith earlier in her career. As she got involved with several of Hindemith’s piano pieces, her attitude changed. Esther put her thoughts on Hidemith’s piano works into a very personal and thought-provoking essay. In it she discusses the rarely-performed Ludus tonalis (we may point to the recordings made by the two Soviet pianists and good friends, Sviatoslav Richter and Anatoly Vedernikov), the Suite “1922” and other pieces; examines the problem of conservative programming, firmly placing the blame on performers (and organizers), rather than composers or listeners; and gives us an insightful overview of Hindemith’s life. Here is an excerpt from the beginning of the essay; you can read the complete piece on Esther’s site. ♫

composer, that he’s too distant, dry, cerebral. That’s what the Swiss pianist Esther Walker thought of Hindemith earlier in her career. As she got involved with several of Hindemith’s piano pieces, her attitude changed. Esther put her thoughts on Hidemith’s piano works into a very personal and thought-provoking essay. In it she discusses the rarely-performed Ludus tonalis (we may point to the recordings made by the two Soviet pianists and good friends, Sviatoslav Richter and Anatoly Vedernikov), the Suite “1922” and other pieces; examines the problem of conservative programming, firmly placing the blame on performers (and organizers), rather than composers or listeners; and gives us an insightful overview of Hindemith’s life. Here is an excerpt from the beginning of the essay; you can read the complete piece on Esther’s site. ♫

On Piano Music of Paul Hindemith.

Like many others before me, I too, in my youth and student days, grew into an unconsciously assumed, hardened and prejudiced (pre)conception of Hindemith. But the very few encounters which I had with this composer as a young pianist – whether it was through occasionally playing one of the Kammermusiks (op. 11) or hearing an orchestral work – forced me each time to cast doubt on this picture which I had of Hindemith. But some years ago, when it happened that I had to study four of Hindemith’s works (the Suite “1922”, the Kammermusik No. 1, The Four Temperaments and the Double Bass Sonata) in a relatively short period of time, I was forced to engage with this music in a much more intensive way than before and was really able to jettison my sometimes-unconscious prejudices. My active interest in Hindemith was aroused.

Of course, there are true Hindemith specialists who devote themselves to this composer and who consequently have a deep access to his output and a profound and unprejudiced knowledge of his life and work.

Since I don’t exactly move in these specialist circles, I believe I can say that, unfortunately even today – especially in Latin countries – Hindemith’s music has the reputation, surely somewhat exaggerated, of being the product of an austere, nonsensical and emotionally-impoverished intellectuality, schoolmasterly and accordingly of little artistic worth.

Even Alfred Brendel, one of the great musical personalities of our time, who is so open, interested and intelligent, and who is able to exert a lasting influence on the next generation, refers to Hindemith in his two books Reflections on Music and Music Taken at his Word in only three passing comments, in which there is no mistaking a rather negative attitude to the composer. In an interview at the end of one of the books Hindemith is quoted in just one sentence, and to quote him so cursorily is usually dangerous, since a little later he would often contradict his pithy, sometimes provocative utterances, or at least qualify them. [Please continue reading here].Permalink

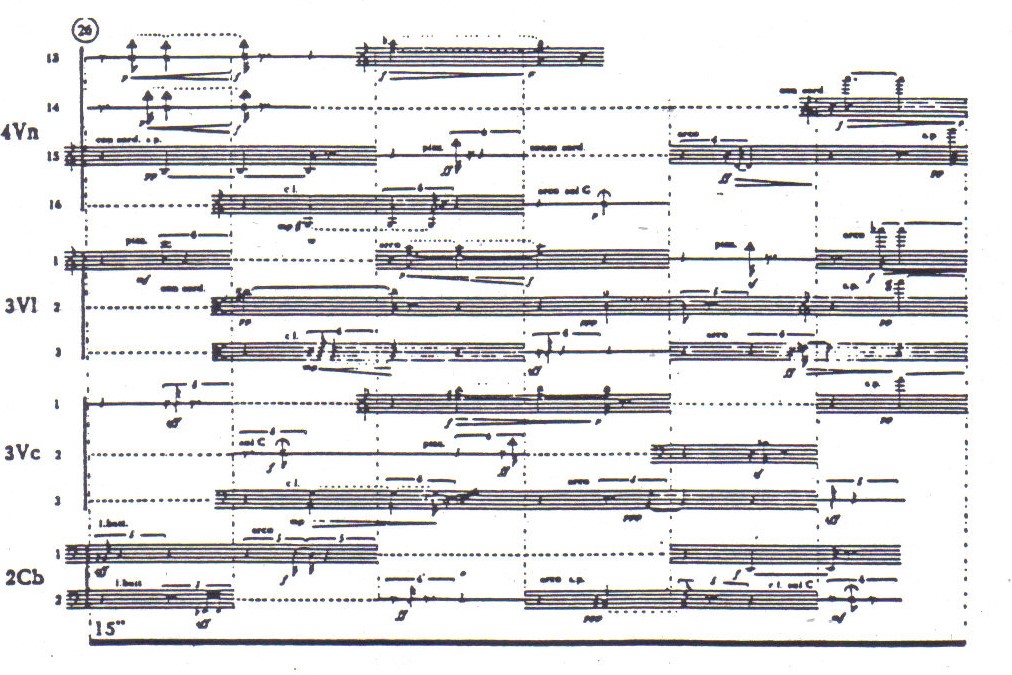

November 20, 2017. Penderecki. Krzysztof Penderecki, one of the best known Polish composers of the 20th century, was born on November 23rd of 1933 in the small town of Dębica in southeastern Poland. The town’s name in Yiddish was Dembitz, and before WWII the majority of the population was Jewish – later, Penderecki would use Jewish music in several compositions. In addition to Polish, Penderecki’s family had Armenian and German roots. The family wasn’t musical, but, as was customary in educated families of the time, Krzysztof took piano lessons. Somebody presented Krzysztof’s father with a violin, and the boy took a liking to the instrument. In 1951 Penderecki moved to Krakow, attending Jagiellonian University first, and then transferring to the Academy of Music. There he studied the violin for one year, but then switched completely to composition. He graduated in 1958 and one year later received three awards for three compositions he submitted to the young composers’ competition, organized by the Polish Composers’ Union. His Strofy (‘Strophes’) received the first prize, and Emanacje (‘Emanations’) and Psalmy Dawida (‘Psalms of David’) shared the second. All compositions were submitted anonymously, and the jury didn’t know that all winning entries were written by the same composer. Since 1956, when Poland opened up after years of Stalinism, cultural life became less controlled. While still a Communist state, culturally Poland was the freest country in the Soviet bloc. New music could be performed, and music of young composers could be heard in the West. One person who became familiar with Penderecki’s work was Heinrich Strobel, principal of the Music Department of the Südwestrundfunk (SWR) Symphony Orchestra of Baden-Baden, one of the leading new Music ensembles. Strobel, a champion of Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen, became a promoter of the works of Krzysztof Penderecki. In 1960, Penderecki’s popularity in the West lead to an interesting episode. He had just completed a piece he initially called 8’37”, for the exact performing duration of the composition, which he later renamed Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima. The piece, scored for 52 string instruments, required unorthodox performing technique, like unusual glissandos, playing on the tailpiece, etc. This, in turn, required unconventional notation, which Penderecki invented

Penderecki’s family had Armenian and German roots. The family wasn’t musical, but, as was customary in educated families of the time, Krzysztof took piano lessons. Somebody presented Krzysztof’s father with a violin, and the boy took a liking to the instrument. In 1951 Penderecki moved to Krakow, attending Jagiellonian University first, and then transferring to the Academy of Music. There he studied the violin for one year, but then switched completely to composition. He graduated in 1958 and one year later received three awards for three compositions he submitted to the young composers’ competition, organized by the Polish Composers’ Union. His Strofy (‘Strophes’) received the first prize, and Emanacje (‘Emanations’) and Psalmy Dawida (‘Psalms of David’) shared the second. All compositions were submitted anonymously, and the jury didn’t know that all winning entries were written by the same composer. Since 1956, when Poland opened up after years of Stalinism, cultural life became less controlled. While still a Communist state, culturally Poland was the freest country in the Soviet bloc. New music could be performed, and music of young composers could be heard in the West. One person who became familiar with Penderecki’s work was Heinrich Strobel, principal of the Music Department of the Südwestrundfunk (SWR) Symphony Orchestra of Baden-Baden, one of the leading new Music ensembles. Strobel, a champion of Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen, became a promoter of the works of Krzysztof Penderecki. In 1960, Penderecki’s popularity in the West lead to an interesting episode. He had just completed a piece he initially called 8’37”, for the exact performing duration of the composition, which he later renamed Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima. The piece, scored for 52 string instruments, required unorthodox performing technique, like unusual glissandos, playing on the tailpiece, etc. This, in turn, required unconventional notation, which Penderecki invented himself. The notation created many problems, as musicians couldn’t figure out what was required of them; Penderecki had to work with the orchestras to explain his intent (you can see a small excerpt on the right). When several European ensembles decided to perform Trenody, Penderecki sent the score to his German publisher. The package never arrived, apparently it got lost in the mail, and Penderecki had to recreate it from memory. Sometime later the score reappeared and was delivered то the addressee. When the two versions were compared, it turned out that they were identical. This provides wonderful proof of the exactness of Penderecki’s intent, the music of necessity of every note despite the seeming chaos of the twelve-tone composition. But the story doesn’t end there. Later, the reason for the score’s long delay was discovered: the custom officials who examined the unusual notation decided that it couldn’t have been music; they suspected that it was a document containing some encoded secret information, probably of military or political significance. Only after a lengthy examination did they discover that this indeed was a music score and sent it to the publisher. Here’s Trenody in the performance by the National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Antoni Wit conducting.

himself. The notation created many problems, as musicians couldn’t figure out what was required of them; Penderecki had to work with the orchestras to explain his intent (you can see a small excerpt on the right). When several European ensembles decided to perform Trenody, Penderecki sent the score to his German publisher. The package never arrived, apparently it got lost in the mail, and Penderecki had to recreate it from memory. Sometime later the score reappeared and was delivered то the addressee. When the two versions were compared, it turned out that they were identical. This provides wonderful proof of the exactness of Penderecki’s intent, the music of necessity of every note despite the seeming chaos of the twelve-tone composition. But the story doesn’t end there. Later, the reason for the score’s long delay was discovered: the custom officials who examined the unusual notation decided that it couldn’t have been music; they suspected that it was a document containing some encoded secret information, probably of military or political significance. Only after a lengthy examination did they discover that this indeed was a music score and sent it to the publisher. Here’s Trenody in the performance by the National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Antoni Wit conducting.

Around 1975 Penderecki’s style, which up to then had been very much modernist, underwent a considerable change and became more melodic, in a neo-romantic way. So different is his music written in the second half of his career that we’ll have to address it separately.Permalink

November 13, 2017. Couperin and Cziffra. During the two weeks that we’ve beenpreoccupied with one photograph, we missed several anniversaries that are clearly worth mentioning. was born on November 10th of 1668 (we’ve written about him a number of times, for example here and here). One of the greatest French composers of the Baroque era, he was especially famous for his harpsichord music. Since the advent of the modern piano, his works are as often performed on this instrument as on the “clavecin,” for which these works were originally written. Here, for example, is Les Barricades Mystérieuses, the title as mysterious as are the barricades in question. It’s the fifth piece in Couperin’s "Ordre 6ème de clavecin." It’s performed by György Cziffra, whose birthday was last week. Cziffra, a piano virtuoso with an unusual biography, was born on November 5th of 1921 into a family of a poor gipsy cabaret performer. His father, a cimbalom player, lived in Paris in the 1910s but was expelled from France as a citizen of an enemy state. György started playing piano at a very early age, imitating his older sister. At the age of five he was already earning money in bars and circuses, playing piano improvisations on melodies suggested by customers. At the age of nine he entered the Franz Liszt Academy of Music in Budapest, becoming their youngest student ever. One of his teachers was the composer Ernst von Dohnányi. At the age of 12 György was performing across Hungary, and at 16 went on a tour of the Netherlands and Scandinavia. In 1942 Cziffra was conscripted, as Hungary was fighting on Nazi Germany’s side in WWII. He was captured by the Soviet partisans and imprisoned till after the war. He returned to Budapest in 1947 and, penniless, had to earn money playing piano in bars and clubs.

was born on November 10th of 1668 (we’ve written about him a number of times, for example here and here). One of the greatest French composers of the Baroque era, he was especially famous for his harpsichord music. Since the advent of the modern piano, his works are as often performed on this instrument as on the “clavecin,” for which these works were originally written. Here, for example, is Les Barricades Mystérieuses, the title as mysterious as are the barricades in question. It’s the fifth piece in Couperin’s "Ordre 6ème de clavecin." It’s performed by György Cziffra, whose birthday was last week. Cziffra, a piano virtuoso with an unusual biography, was born on November 5th of 1921 into a family of a poor gipsy cabaret performer. His father, a cimbalom player, lived in Paris in the 1910s but was expelled from France as a citizen of an enemy state. György started playing piano at a very early age, imitating his older sister. At the age of five he was already earning money in bars and circuses, playing piano improvisations on melodies suggested by customers. At the age of nine he entered the Franz Liszt Academy of Music in Budapest, becoming their youngest student ever. One of his teachers was the composer Ernst von Dohnányi. At the age of 12 György was performing across Hungary, and at 16 went on a tour of the Netherlands and Scandinavia. In 1942 Cziffra was conscripted, as Hungary was fighting on Nazi Germany’s side in WWII. He was captured by the Soviet partisans and imprisoned till after the war. He returned to Budapest in 1947 and, penniless, had to earn money playing piano in bars and clubs.  In 1950 he attempted to escape communist Hungary but was captured and imprisoned again. His guards, knowing that he was a pianist, beat his hands and wrists. He was released in 1953. The physical recovery was slow (for the rest of his life he performed with a leather band on his wrist to support ligaments damaged in prison), but two years later he was in good enough form to win the 1955 Franz List competition in Budapest. In 1956, during the Hungarian Uprising, Cziffra escaped to Vienna, where he gave a well-received recital later that year, and then moved to Paris. Cziffra played across Europe and in the US. In 1977 he set up a Cziffra Foundation in Senlis, France, in support of young musicians. Cziffra, with his tremendous technical skills, was acknowledged as a great interpreter of the works of Liszt. Here’s another piece by Couperin, L'Anguille (The eel). And here is Liszt’s Tarantella, from Venezia e Napoli section of Années de pèlerinage. Cziffra, who by the end of his life was suffering of lung cancer, died of a heart attack in Longpont-sur-Orge, outside of Paris, on January 15th of 1994.

In 1950 he attempted to escape communist Hungary but was captured and imprisoned again. His guards, knowing that he was a pianist, beat his hands and wrists. He was released in 1953. The physical recovery was slow (for the rest of his life he performed with a leather band on his wrist to support ligaments damaged in prison), but two years later he was in good enough form to win the 1955 Franz List competition in Budapest. In 1956, during the Hungarian Uprising, Cziffra escaped to Vienna, where he gave a well-received recital later that year, and then moved to Paris. Cziffra played across Europe and in the US. In 1977 he set up a Cziffra Foundation in Senlis, France, in support of young musicians. Cziffra, with his tremendous technical skills, was acknowledged as a great interpreter of the works of Liszt. Here’s another piece by Couperin, L'Anguille (The eel). And here is Liszt’s Tarantella, from Venezia e Napoli section of Années de pèlerinage. Cziffra, who by the end of his life was suffering of lung cancer, died of a heart attack in Longpont-sur-Orge, outside of Paris, on January 15th of 1994.

A note: another wonderful pianist, the French-born German, Walter Gieseking, was also born on November 5th but 26 years earlier, in 1895.Permalink

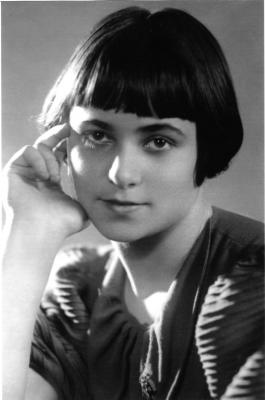

November 6, 2017. Old picture, part II. Last week we identified three people in the picture, below, wrote about two of them, Busya Goldshtein and Yakov Flier, and just touched upon Rosa Tamarkina, who stands next to Flier, slightly behind. Tamarkina, who had just turned 20 when the picture was made, was already a laureate of several competitions. She was born in Kiev in 1920, started her studies there but moved to Moscow when she was 11, after being accepted into a special group for talented kids organized by Alexander Goldenweiser. At the age of 15 she won the first prize at the All-Union Performers’ competition. One year later she conquered the hearts of both the jury and the public while playing at the Chopin Competition in Warsaw. She was awarded the second prize, behind only Yakov Zak, who was seven years her senior. Heinrich Neuhaus, a jury member, talked about her as a mature, fully developed musician. After the Chopin, still a student, she was engaged to play concerts across the country; practically all of them were sold out.

Tamarkina, who stands next to Flier, slightly behind. Tamarkina, who had just turned 20 when the picture was made, was already a laureate of several competitions. She was born in Kiev in 1920, started her studies there but moved to Moscow when she was 11, after being accepted into a special group for talented kids organized by Alexander Goldenweiser. At the age of 15 she won the first prize at the All-Union Performers’ competition. One year later she conquered the hearts of both the jury and the public while playing at the Chopin Competition in Warsaw. She was awarded the second prize, behind only Yakov Zak, who was seven years her senior. Heinrich Neuhaus, a jury member, talked about her as a mature, fully developed musician. After the Chopin, still a student, she was engaged to play concerts across the country; practically all of them were sold out.  She was even awarded the order of the Barge of Honor and, at the age of 19, “elected” (“appointed” would be a better description) into the Moscow Soviet. Rosa married Emil Gilels in 1940 but it was not a happy union and in 1943 they divorced. In 1946 she fell ill; the diagnosis was terrible: Hodgkin's lymphoma. She continued performing, often with a high fever; the public didn’t know about her condition. Rosa Tamarkina died on August 5th of 1950 at the age of 30.

She was even awarded the order of the Barge of Honor and, at the age of 19, “elected” (“appointed” would be a better description) into the Moscow Soviet. Rosa married Emil Gilels in 1940 but it was not a happy union and in 1943 they divorced. In 1946 she fell ill; the diagnosis was terrible: Hodgkin's lymphoma. She continued performing, often with a high fever; the public didn’t know about her condition. Rosa Tamarkina died on August 5th of 1950 at the age of 30.

Next to Tamarkina stands Elizabeth Gilels, Emil’s younger sister. The family already had a pianist, so Elizabeth picked the violin as her instrument. Like Busya Goldshtein, she was a student of Peter Stolyarky, who also taught David Oistrakh, Nathan Milstein and many other talented violinists. When they were young, Elisabeth and Emil often played together. In 1935, just 16 years old, she took the Second prize, behind Oistrakh, at the 2nd All-Union Performers’ competition. In 1937, at the 1st Ysaÿe competition (it was later renamed as the Queen Elisabeth Competition) she took the 3rd prize. Again, Oistrakh was first and the Soviet violinists took all but one prizes from the first to the sixth. Four of the six were Stolyarsky’s students and the only non-Soviet violinist, Ricardo Odnoposoff, who took the 2nd prize, was from an Argentinian Russian-Jewish family. In 1949 Elizabeth married Leonid Kogan. Superb soloists, they created a duo and together recorded Bach, Vivaldi, and other composers. Elisabeth Gilels and Leonid Kogan had two children, Pavel and Nina. Pavel, also a brilliant violinist, eventually turned to conducting. Nina was a successful pianist and often played with her father. Pavel’s son Dmitry, also a violinist, died unexpectedly two months ago at the age of 38.

Yakov Zak, the second from the right, was 26 when this picture was made. He was born in Odessa, as was Goldshtein and the Gilelses. He graduated from the Odessa in 1932 and went to Moscow for post-graduate studies with Heinrich Neuhaus. In 1935 he took the third prize at the Second All-Union Performers’ Competition. Then, in 1937, he triumphed in Warsaw, winning the first prize at the Chopin Piano competition. Zak had a distinguished performing career; he was considered to be an intellectual pianist compared to, for example, the more “romantic” Flier. After the war he successfully performed in many countries across Europe and in the US. He was also one of the most respected professors at the Moscow Conservatory; among his students were Nikolai Petrov, Eliso Virsaladze, and Evgeny Mogilevsky. Zak died in Moscow in 1976.

And the serious young man on the right is, of course, Emil Gilels. We wrote about him not long ago.Permalink