Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

April 16, 2018. . Nikolai Myaskovsky, a Russian composer, was born this week, on April 20th of 1881. Prolific (he wrote 27 symphonies), he was widely performed during his lifetime in the Soviet Union and, to a lesser extent, in Europe and the US. He was often criticized by the Soviet music establishment and almost as often awarded state prizes; these days he’s mostly forgotten. Myaskovsky deserves to be written about, but today we’ll focus on Tomás Luis de Victoria, one of the great composers of the Renaissance, for whom we never have a fixed date as we don’t know when hewas born.

In 1583 Victoria dedicated the second volume of masses (Missarum libri duo) to King Philip II and expressed the desire to return to Spain and lead the life of a priest. His wish was granted: Victoria was named the chaplain to the Dowager Empress María. Empress Maria lived in the Monasterio de las Descalzas Reales. Masses at the convent were served daily, with Victoria acting as the choir master and organist. After dowager’s death in 1603 he remained at the convent in a position endowed by Maria. Victoria was held in very high esteem, was paid very well, and was free to travel. In 1594, he happened to be in Rome when Palestrina died; the funeral mass was celebrated at Saint Peter’s Basilica, with Victoria in attendance. By the end of his own life, Victoria’s music was played all over Europe and even in the New World: his masses were very popular in Mexico and Bogotá. He died on August 20th of 1611 and was buried at the Monasterio de las Descalzas.

Victoria’s masterpiece is Officium Defunctorum, a prayer cycle for the deceased, which includes settings of seven movements of the Funeral Mass and another three pieces. Officium Defunctorum was written on the death of Dowager Empress María in 1603. You can hear all 10 movement of Officium Defunctorum by searching our library. It is performed, with extraordinary clarity and style, by the Spanish ensemble Musica Ficta. Another great interpreter of the music of Victoria is the ensemble The Sixteen, directed by Harry Christophers. Here, in their performance, in Victoria’s Magnificat Sexti Toni, one of the several settings of Magnificat composed by the great Spaniard.Permalink

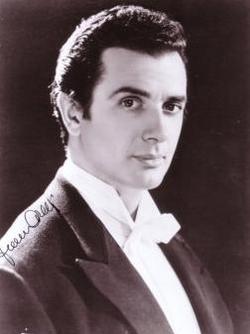

April 9, 2018. Two singers. Franco Corelli’s birthday was yesterday: he was born on April 8th of 1921. One of the greatest tenors of the mid-20th century, he, together with Giuseppe Di Stefano and Mario Del Monaco, brought the level of tenor singing to heights which seem unreachable today. Add to it two supreme sopranos, Maria Callas and Renata Tebaldi, the great baritone Tito Gobbi, the mezzo Giulietta Simionato, the base Cesare Siepi – all of them at the top of their form in the mid-1950s. What a glorious era! Corelli may not have had the most beautiful voice, but the power, clarity, phenomenal breath control and sheer excitement he generated were incomparable. Listen, for example, to this 1955 recording of Cavaradossi’s aria E lucevan le stele from Puccini’s Tosca. One may quibble with the interpretations, with the notes he holds a bit too long – just because he can! – but it’s singing at the very highest level. Or a small sample from the legendary performance of the same opera in the Teatro Regio di Parma on January 21, 1967. Tosca is Virginia Gordoni, Scarpia – Attilio d'Orazi, but it’s Corelli’s 12 seconds of A-sharp in Vittoria, Vittoria at the very end of this two-minute excerpt that brought the theater down. We cut out the ensuing pandemonium (the word “ovation” isn’t strong enough) because it just wouldn’t stop; one couldn’t hear anything anyway, even though the orchestra continued to play (here). Corelli was born in a provincial city of Ancona, his family wasn’t musical, and Franco entered the Pesaro conservatory almost by chance. Even there, he mostly taught himself, following the technique of Mario del Monaco and listening to the old recordings of Caruso, Gigli and Lauri-Volpi. Corelli started singing professionally in 1951; in 1953, in the Rome Opera, he sung Pollione in Bellini's Norma with Maria Callas in the title role. Callas was taken by Corelli’s voice, and in the following years the two sung together on many occasions, especially at La Scala. Corelli also sung with Renata Tebaldi in the famous production of La forza del destino at the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples (YouTube has a large excerpt from it: Mario del Monaco, mentioned in the title, didn’t sing in this particular production). Corelli sung his debut performance at the Metropolitan Opera in 1961 as Manrico in Il Trovatore with Leontine Price. He performed at the Met till 1975, even though in the early 1970s his voice lost some of its luster. In 1976, at the age of 55, Corelli quit. Even though he personally disliked voice teachers, he became one himself, and a very successful one. Franco Corelli died in Milan on October 29th of 2003.

unreachable today. Add to it two supreme sopranos, Maria Callas and Renata Tebaldi, the great baritone Tito Gobbi, the mezzo Giulietta Simionato, the base Cesare Siepi – all of them at the top of their form in the mid-1950s. What a glorious era! Corelli may not have had the most beautiful voice, but the power, clarity, phenomenal breath control and sheer excitement he generated were incomparable. Listen, for example, to this 1955 recording of Cavaradossi’s aria E lucevan le stele from Puccini’s Tosca. One may quibble with the interpretations, with the notes he holds a bit too long – just because he can! – but it’s singing at the very highest level. Or a small sample from the legendary performance of the same opera in the Teatro Regio di Parma on January 21, 1967. Tosca is Virginia Gordoni, Scarpia – Attilio d'Orazi, but it’s Corelli’s 12 seconds of A-sharp in Vittoria, Vittoria at the very end of this two-minute excerpt that brought the theater down. We cut out the ensuing pandemonium (the word “ovation” isn’t strong enough) because it just wouldn’t stop; one couldn’t hear anything anyway, even though the orchestra continued to play (here). Corelli was born in a provincial city of Ancona, his family wasn’t musical, and Franco entered the Pesaro conservatory almost by chance. Even there, he mostly taught himself, following the technique of Mario del Monaco and listening to the old recordings of Caruso, Gigli and Lauri-Volpi. Corelli started singing professionally in 1951; in 1953, in the Rome Opera, he sung Pollione in Bellini's Norma with Maria Callas in the title role. Callas was taken by Corelli’s voice, and in the following years the two sung together on many occasions, especially at La Scala. Corelli also sung with Renata Tebaldi in the famous production of La forza del destino at the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples (YouTube has a large excerpt from it: Mario del Monaco, mentioned in the title, didn’t sing in this particular production). Corelli sung his debut performance at the Metropolitan Opera in 1961 as Manrico in Il Trovatore with Leontine Price. He performed at the Met till 1975, even though in the early 1970s his voice lost some of its luster. In 1976, at the age of 55, Corelli quit. Even though he personally disliked voice teachers, he became one himself, and a very successful one. Franco Corelli died in Milan on October 29th of 2003.

Montserrat Caballé, one of the greatest sopranos of the second half of the 20th century, will turn 85 in three days. Caballé was born on April 12th of 1933 in Barcelona. A real bel canto soprano (unlike most of the sopranos on stage today), she was one of the best Normas ever. She also excelled in Donizetti, especially as Mary Queen of Scots in Maria Stuarda and Elizabeth I in Roberto Devereaux. She also sung in many Verdi operas. Caballé had her debut at the Metropolitan Opera in 1965 in a not very typical role of Marguerite in Gounod’s Faust. Since then she has performed at the Met dozens of times, singing in several Verdi operas, Puccini's Turandot and operas by Donizetti. Her official debut in La Scala happened only in 1970, when she was already world-famous. She often partnered with the much younger José Carreras (while at the same time Joan Sutherland took under her wing a younger Luciano Pavarotti). There are hundreds of great recording of Caballé’s art; here is an excerpt from Roberto Devereu. The live recording was made in Venice in 1972. Bruno Bartoletti conducts the orchestra of the Teatro la Fenice.Permalink

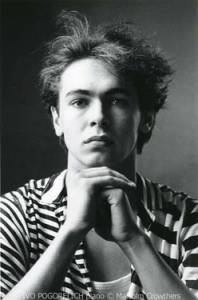

April 3, 2018. Haydn, Pogorelich. We’d like to come back to Joseph Haydn, whom we mentioned, rather perfunctorily, last week. As we were looking for a sample of Richter’s recording of a Haydn sonata (Richter made several and played Haydn often) we came across one made by Ivo Pogorelich in 1991. It was a recording of a wonderful Piano Sonata no. 30 in D major, Hoboken XVI:19, composed in 1767. Pogorelich, born in Belgrade, is one of the most unusual pianists of his generation. His career began with a scandal: in 1980 the jury of the Chopin International Competition eliminated him after the second round. Martha Argerich resigned in protest (she was not the only one to object, so did Nikita Magaloff and Paul Badura-Skoda, although they didn’t quit). The publicity generated by the Warsaw scandal helped Pogorelich’s career. While some of his interpretations were eccentric, they were not outlandish, on top of which he had a flawless technique. In 1981 Pogorelich was invited to the Carnegie Hall (he played there many times; his 1992 performance of Balakirev’s Islamey became legendary). That same year, 1981, he debuted in London, and a year later he was signed by Deutsche Grammophon. Pogorelich had studied in the Soviet Union since 1976; the year of the Chopin Competition he married his teacher, Alisa Kezheradze, 21 years his senior. Little is known about Kezheradze. When she met Pogorelich, she was married to a Soviet functionary, living in a large apartment in the center of Moscow. She taught piano at the Music department of the Pedagogic Institute (Vladimir Genis, a Russian-German composer and pianist who studied there, remembers Kezheradze as “the only bright spot in that theater of the absurd, … striking, slim, of indeterminate age, with a face of a Georgian princess.” She also worked with several Conservatory students. One of them was the young Mikhail Pletnev, whom Kezheradze prepared for the 1978 Tchaikovsky Competition after the death of Pletnev’s professor, Yakov Flier, six months earlier. Pletnev went on to win the competition. By then Kezheradze had already divorced her first husband. Her and Ivos’ marriage application was first rejected, but later the authorities relented, allowing them to marry and emigrate. Kezheradze and Pogorelich moved to Europe where they lived together till her death of liver cancer in 1996. Pogorelich, devastated by the loss, practically abandoned the concert stage. When, some years later, he resumed his public career, the eccentricities of his earlier years developed into interpretations that were often incomprehensible. He took the tempos so slow that the whole musical structure fell apart (for example, his recording of Chopin’s Nocturne op. 48, no. 1 takes an insane but mesmerizing nine minutes and ten seconds. Arthur Rubinstein plays it, stately, in a 5:47). He’d play either pianissimo or fortissimo, with strange accents. Anthony Tommasini of the New York Time finished his 2006 review of a Carnegie Hall concert thusly: "Here is an immense talent gone tragically astray. What went wrong?" It’s impossible to answer this question, but there are many of Pogorelich’s recordings that could be enjoyed today. The Hob. XVI:19 is one of them. Every one of Haydn’s musical ideas is brilliantly enunciated, every line is clear, the sound is beautiful, everything is balanced – a great performance overall. Listen to it here.Permalink

Pogorelich in 1991. It was a recording of a wonderful Piano Sonata no. 30 in D major, Hoboken XVI:19, composed in 1767. Pogorelich, born in Belgrade, is one of the most unusual pianists of his generation. His career began with a scandal: in 1980 the jury of the Chopin International Competition eliminated him after the second round. Martha Argerich resigned in protest (she was not the only one to object, so did Nikita Magaloff and Paul Badura-Skoda, although they didn’t quit). The publicity generated by the Warsaw scandal helped Pogorelich’s career. While some of his interpretations were eccentric, they were not outlandish, on top of which he had a flawless technique. In 1981 Pogorelich was invited to the Carnegie Hall (he played there many times; his 1992 performance of Balakirev’s Islamey became legendary). That same year, 1981, he debuted in London, and a year later he was signed by Deutsche Grammophon. Pogorelich had studied in the Soviet Union since 1976; the year of the Chopin Competition he married his teacher, Alisa Kezheradze, 21 years his senior. Little is known about Kezheradze. When she met Pogorelich, she was married to a Soviet functionary, living in a large apartment in the center of Moscow. She taught piano at the Music department of the Pedagogic Institute (Vladimir Genis, a Russian-German composer and pianist who studied there, remembers Kezheradze as “the only bright spot in that theater of the absurd, … striking, slim, of indeterminate age, with a face of a Georgian princess.” She also worked with several Conservatory students. One of them was the young Mikhail Pletnev, whom Kezheradze prepared for the 1978 Tchaikovsky Competition after the death of Pletnev’s professor, Yakov Flier, six months earlier. Pletnev went on to win the competition. By then Kezheradze had already divorced her first husband. Her and Ivos’ marriage application was first rejected, but later the authorities relented, allowing them to marry and emigrate. Kezheradze and Pogorelich moved to Europe where they lived together till her death of liver cancer in 1996. Pogorelich, devastated by the loss, practically abandoned the concert stage. When, some years later, he resumed his public career, the eccentricities of his earlier years developed into interpretations that were often incomprehensible. He took the tempos so slow that the whole musical structure fell apart (for example, his recording of Chopin’s Nocturne op. 48, no. 1 takes an insane but mesmerizing nine minutes and ten seconds. Arthur Rubinstein plays it, stately, in a 5:47). He’d play either pianissimo or fortissimo, with strange accents. Anthony Tommasini of the New York Time finished his 2006 review of a Carnegie Hall concert thusly: "Here is an immense talent gone tragically astray. What went wrong?" It’s impossible to answer this question, but there are many of Pogorelich’s recordings that could be enjoyed today. The Hob. XVI:19 is one of them. Every one of Haydn’s musical ideas is brilliantly enunciated, every line is clear, the sound is beautiful, everything is balanced – a great performance overall. Listen to it here.Permalink

March 26, 2018. Richter and Haydn. Last week we started writing about the pianist Sviatoslav Richter, and made it all the way to 1941, when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. Richter, 26 years old, joined many other musicians who continued to perform during the war, often on the front line. In January 1943 he premiered Prokofiev’s Piano Sonata no. 7, one of the three so-called “War Sonatas” (sonatas sixth through eighth). Richter already new Prokofiev: they met over Prokofiev’s Sonata no. 6..jpg) Premiered by the composer, the sonata became part of Richter’s repertoire; he played it on his first “official” Moscow concert in 1940. And even though he didn’t premier Prokofiev’s Eighth (Emil Gilels did), he played it at the Third All-Union competition in 1945, which Richter won (Victor Merzhanov shared the first prize with him). Here’s a live recording of Prokofiev’s Piano Sonata no. 7 from 1958.

Premiered by the composer, the sonata became part of Richter’s repertoire; he played it on his first “official” Moscow concert in 1940. And even though he didn’t premier Prokofiev’s Eighth (Emil Gilels did), he played it at the Third All-Union competition in 1945, which Richter won (Victor Merzhanov shared the first prize with him). Here’s a live recording of Prokofiev’s Piano Sonata no. 7 from 1958.

In 1943 Richter met Nina Dorliak, a fine opera and chamber singer. Nina was born into a prominent family: her father was a deputy to the Czar’s finance minister; her mother in her youth was a lady-in-waiting to dowager Empress Maria, later she became a well-known singer herself. Considering such legacy, it’s a miracle that Nina was not arrested during the Great Purge. Dorliak and Richter became good friends and played many concerts together. In 1945 Richter, most likely a closeted homosexual (he never talked about it), proposed to Nina. They married in 1945 and stayed together to the end of his life.

After the war, Richter, by then one of the most popular young pianists, extensively toured the Soviet Union and the countries of the Eastern bloc, but not in the West. Part of the “problem” was his parents (his German father was executed at the beginning of the war, his mother moved to Germany), partly because of his connections to the artists out of favor with the State, such as Prokofiev, who, from 1948 on was repeatedly criticized as “formalist,” as well as the poet Boris Pasternak. All of this changed with Khrushchev’s “thaw,” when Richter was allowed to go on a tour of the US. He played his first American concert on October 15th of 1960 in Chicago (Brahms’s Second Piano Concerto with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Erich Leinsdorf). On October 19th he played a massive concert in Carnegie Hall: five Beethoven sonatas, including the Appassionata (no. 23); two Etudes from Chopin’s op. 10, a Schubert’s Impromptu (D 899, no. 4) and Robert Schumann’s Fantasiestücke, opus 12, no. 2. He played another concert several days later, this one consisting of Prokofiev’s piece: piano sonatas nos. 6 and 8, and smaller pieces. Two more concerts followed: Haydn's Sonata No. 50 in C Major, Schumann and Debussy in one, and Schumann, Chopin, Ravel and Scriabin in another. He continued the tour through the end of the year, visiting Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago again, and the West coast. In December he played Carnegie Hall two more times. Altogether, he played more than 60 different pieces, including five different piano concertos: Tchaikovsky’s First, Brahms’s Second, Beethoven’s First, Liszt’s Second, and Dvořák’s. It’s difficult to think of another pianist with such a breadth of repertoire.

Franz Joseph Haydn was born on March 31st of 1732. Richter played many of his pianos sonatas (and also the piano concerto). Here’s Haydn’s Piano Sonata in C major, Hob.XVI:35. It was recorded in 1967.Permalink

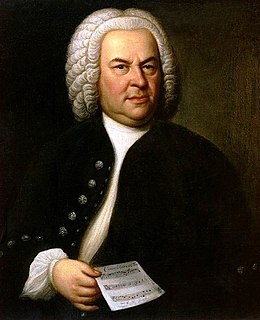

March 19, 2018. Bach and Richter. In two days we’ll celebrate Johann Sebastian Bach’s 333rd birthday. We’ve written about Bach’s early years in Leipzig (here and here), the years that were dedicated to his work as the Kantor at Tomasschule, the school of the St. Thomas church, wherehe also served as the choir director. All along Bach was the music director of two other important churches in the city, St. Nicholas church (Nikolaikirche) and Paulinerkirche, the University church. His duties included writing music for Sunday services, and in the early Leipzig years he produced an astonishing number of cantatas, more than 300 altogether, of which 200 plus are extant. He also wrote several Passions, of which the St. John’s and St. Matthew survive. By the year 1729 the accumulated volume of compositions was such that he could allow himself to either perform the old music, or reuse pre-existing material, creating what is called “parody” cantatas. (The old and rather unusual musical term “parody,” or imitation, has nothing to do with humor. “Parody mass,” for example, was one of the major types of Renaissance mass where the composer used – and acknowledged – the borrowed material. The intellectual property rules were very vague in those days). By the year 1729, Bach’s creative forces shifted away from church music to secular music. One impetus was Collegium Musicum, of which Bach was appointed the director in 1729. Collegium Musicum was created by Telemann in 1702 as an association of professional musicians and students for the purpose of producing regular public concerts. During the winter the concerts were given at Café Zimmermann, one of the largest coffee houses in Leipzig (the building was constructed in 1715; it was destroyed during the Allied air raid in 1943). Bach’s Coffee Cantata, BWV 211, was probably premiered at Zimmermann’s. Several of Bach’s keyboard and violin concertos were written for Collegium Musicum. It’s quite likely that Wilhelm Friedemann and Carl Philipp Emanuel, two of Bach’s sons, performed with the Collegium. Bach also continued writing keyboard pieces. Those were published in four books called Clavier-Übung, or keyboard exercise. The first volume, published in 1731, contained six partitas for harpsichord, the second, in 1735 – two pieces, the Italian Concerto BWV 971 and Overture in the French style, BWV 831. You can hear the Italian Concerto here, and the Overture – here. Both are performed by Sviatoslav Richter; the recordings were made in 1991, when Richter was 76.

important churches in the city, St. Nicholas church (Nikolaikirche) and Paulinerkirche, the University church. His duties included writing music for Sunday services, and in the early Leipzig years he produced an astonishing number of cantatas, more than 300 altogether, of which 200 plus are extant. He also wrote several Passions, of which the St. John’s and St. Matthew survive. By the year 1729 the accumulated volume of compositions was such that he could allow himself to either perform the old music, or reuse pre-existing material, creating what is called “parody” cantatas. (The old and rather unusual musical term “parody,” or imitation, has nothing to do with humor. “Parody mass,” for example, was one of the major types of Renaissance mass where the composer used – and acknowledged – the borrowed material. The intellectual property rules were very vague in those days). By the year 1729, Bach’s creative forces shifted away from church music to secular music. One impetus was Collegium Musicum, of which Bach was appointed the director in 1729. Collegium Musicum was created by Telemann in 1702 as an association of professional musicians and students for the purpose of producing regular public concerts. During the winter the concerts were given at Café Zimmermann, one of the largest coffee houses in Leipzig (the building was constructed in 1715; it was destroyed during the Allied air raid in 1943). Bach’s Coffee Cantata, BWV 211, was probably premiered at Zimmermann’s. Several of Bach’s keyboard and violin concertos were written for Collegium Musicum. It’s quite likely that Wilhelm Friedemann and Carl Philipp Emanuel, two of Bach’s sons, performed with the Collegium. Bach also continued writing keyboard pieces. Those were published in four books called Clavier-Übung, or keyboard exercise. The first volume, published in 1731, contained six partitas for harpsichord, the second, in 1735 – two pieces, the Italian Concerto BWV 971 and Overture in the French style, BWV 831. You can hear the Italian Concerto here, and the Overture – here. Both are performed by Sviatoslav Richter; the recordings were made in 1991, when Richter was 76.

One of the greatest pianists of the 20th century, Sviatoslav Richter was born on March 20th of 1915 in Zhitomir, Ukraine. His father, Teofil Richter, was a pianist and a German expat, his mother was Russian. The family moved to Odessa in 1921. Even though Teofil taught at the Conservatory, little Sviatoslav studied music mostly on his own. At the age of 15 he started working at the local opera as a rehearsal pianist. Without any further formal education, he auditioned for Heinrich Neuhaus at the Moscow Conservatory in 1937. Neuhaus, who had the strongest class in all of the Conservatory (Emil Gilels and Radu Lupu were his students), accepted him immediately. Richter’s studies didn’t last long, though: he wouldn’t attend the non-music classes, was kicked out after several months and returned to Odessa. Neuhaus, who considered his pupil a genius, insisted that he return. Richter was re-admitted but got his official diploma only in 1947. That didn’t stop him from playing concerts: in 1940 he premiered Prokofiev’s Sixth Piano sonata, then played his first Moscow concert with the orchestra. As Germany attacked Russia in 1941, Sviatoslav’s life, as that of every other Soviet citizen, changed forever. His father, as so many Russian Germans, was arrested and later executed. His mother disappeared and was presumed dead; only many years later would Sviatoslav find out that she eventually made it to Germany. To be continued next week. Permalink

March 12, 2018. Malipiero and more. Hugo Wolf, a tremendously talented Austrian composer who died tragically young in a syphilis-induced delirium, was born on March 13th of 1860. Last your we dedicated an entry to him, so here are two of his songs. First, Schlafendes Jesuskind (Sleeping Baby Jesus) from the cycle Mörike-Lieder is sung by the French baritone Gérard Souzay with Dalton Baldwin at the piano. Then, Nachtzaube (Night magic), from Eichendorff Lieder. It’s performed by Elisabeth Schwarzkopf and Gerald Moore.

Georg Philipp Telemann, born on March 14th of 1681 was, in many ways, Wolf’s direct opposite. He lived a long life (86 years), wrote an immense number of pieces (1700 cantatas, numerous oratorios, more than 50 operas and a large number of instrumental suites, concertos and sonatas). He was in good health for most of his life, had many children, and clearly didn’t suffer from depression, as Wolf did all his life. The challenge with Telemann is to find the great works (and he wrote some wonderful music) among his immense, and sometimes mediocre, output. La Changeante, Telemann’s Overture for Strings in G minor (TWV 55:g2) seems to fit the bill well. Here it’s performed by Collegium Instrumentale Brugense, Patrick Peire conducting.

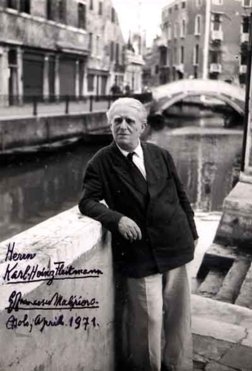

We’ve never written about the 20th century Italian composer, Gian Francesco Malipiero. Malipiero was born on March 18th of 1882 in Venice. His grandfather was an opera composer, his father – a pianist and conductor. Malipiero’s childhood was troubled. His parents divorced, and he spent several years with his father, traveling to Trieste, Berlin and Vienna, where he attended the conservatory. At the age of 17 he left his father and returned to Venice, to his mother’s home. He immersed himself in the newly discovered music of Frescobaldi and Monteverdi; he later considered it an important part of his musical education. In 1913 he went to Paris, where, in addition to all the requisite Frenchmen, he met Alfredo Casella, who became his friend for life. It was Casella who recommended Malipiero attend the premiere of The Rite of Spring; Stravinsky’s music made a big impression on Malipiero. He moved to Rome in 1917, when in the course of WWI, Austrian forces threatened Venice. There he continued his collaboration with Casella, first at the Società Italiana di Musica Moderna, then, in 1923, when they founded the Corporazione delle Nuove Musiche. Reorganization of Italian music was one of Mussilini’s favorite projects, and for a while Malipiero won his favor: he had at least three personal audiences with the dictator. This all ended in 1934, when Malipiero’s opera La favola del figlio cambiato was condemned by the official press. Malipiero tried to get back on Mussolini’s good side and dedicated his next opera, Giulio Cesare, to him, but that didn’t help: Malipiero’s request for an audience was rejected. In 1922 Malipiero bought a house in Asolo, a pretty hilltop town not far from Venice, and lived there for the rest of his life. In 1940 he became a professor at the Venice Liceo Musicale (Conservatory). One of his students there was Luigi Nono. It was through Malipiero that Nono met Bruno Maderna. In addition to teaching, Malipiero edited the complete works of Claudio Monteverdi. He died on August 1st of 1973.

and he spent several years with his father, traveling to Trieste, Berlin and Vienna, where he attended the conservatory. At the age of 17 he left his father and returned to Venice, to his mother’s home. He immersed himself in the newly discovered music of Frescobaldi and Monteverdi; he later considered it an important part of his musical education. In 1913 he went to Paris, where, in addition to all the requisite Frenchmen, he met Alfredo Casella, who became his friend for life. It was Casella who recommended Malipiero attend the premiere of The Rite of Spring; Stravinsky’s music made a big impression on Malipiero. He moved to Rome in 1917, when in the course of WWI, Austrian forces threatened Venice. There he continued his collaboration with Casella, first at the Società Italiana di Musica Moderna, then, in 1923, when they founded the Corporazione delle Nuove Musiche. Reorganization of Italian music was one of Mussilini’s favorite projects, and for a while Malipiero won his favor: he had at least three personal audiences with the dictator. This all ended in 1934, when Malipiero’s opera La favola del figlio cambiato was condemned by the official press. Malipiero tried to get back on Mussolini’s good side and dedicated his next opera, Giulio Cesare, to him, but that didn’t help: Malipiero’s request for an audience was rejected. In 1922 Malipiero bought a house in Asolo, a pretty hilltop town not far from Venice, and lived there for the rest of his life. In 1940 he became a professor at the Venice Liceo Musicale (Conservatory). One of his students there was Luigi Nono. It was through Malipiero that Nono met Bruno Maderna. In addition to teaching, Malipiero edited the complete works of Claudio Monteverdi. He died on August 1st of 1973.

Here’s Malipiero’s Quartet no.1 Rispetti e strambotti, from 1920. It’s performed by the Orpheus String Quartet.Permalink