Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

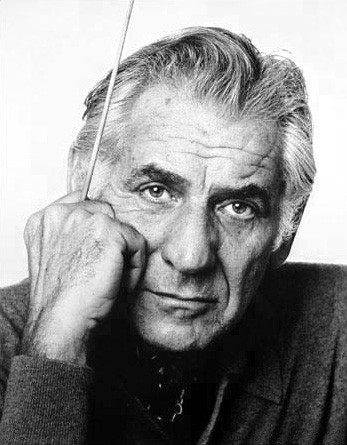

August 20, 2018. Bernstein 100. August 25th will mark the 100th birthday of Leonard Bernstein, American composer, conductor, pianist and music educator. Musical America has been celebrating this event for the past 12 months, and for good reason: Bernstein’s influence on American culture cannot be overestimated. He was one of the most important American composers of the 20th century; his tenure as the music director of New York Philharmonic was probably the most significant in the orchestra’s history. He wrote wonderful musicals, such as Candide and West Side Story, the latter being made world famous when he adapted it to the film (everybody remembers the tunes but it’s worth listening to it again – for all its simplicity it’s amazingly sophisticated music). And of course, his long series of Young People’s Concerts remain one of the great examples of music education: he didn’t condescend to kids, didn’t try to dumb-down the approach (in his very first concert in 1958 he played a piece by Anton Webern) but shared with them his love and understanding of music in his own, communicative and contagiously enthusiastic way. Bernstein was a Renaissance figure, and much was written about him, especially in preparation to the centenary. We’ll address one small aspect of his creative work: the (re)introduction of the music of Mahler into the American culture. Mahler is so ubiquitous these days that it’s hard to imagine that up to the late 1950s his music was rarely heard in concerts.

composers of the 20th century; his tenure as the music director of New York Philharmonic was probably the most significant in the orchestra’s history. He wrote wonderful musicals, such as Candide and West Side Story, the latter being made world famous when he adapted it to the film (everybody remembers the tunes but it’s worth listening to it again – for all its simplicity it’s amazingly sophisticated music). And of course, his long series of Young People’s Concerts remain one of the great examples of music education: he didn’t condescend to kids, didn’t try to dumb-down the approach (in his very first concert in 1958 he played a piece by Anton Webern) but shared with them his love and understanding of music in his own, communicative and contagiously enthusiastic way. Bernstein was a Renaissance figure, and much was written about him, especially in preparation to the centenary. We’ll address one small aspect of his creative work: the (re)introduction of the music of Mahler into the American culture. Mahler is so ubiquitous these days that it’s hard to imagine that up to the late 1950s his music was rarely heard in concerts.

It’s not quite true that Mahler wasn’t performed at all. Bruno Walter, Mahler’s assistant and friend, programmed his music into some concerts and made several recordings, including Das Lied von der Erde with Kathleen Ferrier and Julius Patzak. Willem Mengelberg, the Dutch conductor who met Mahler in 1902 and championed his music for the following forty years, did much to promote Mahler’s music in Europe (unfortunately, he was also a Nazi supporter, which didn’t help his legacy). Some years later, John Barbirolli started playing Mahler regularly in Britain. But of the two leading conductors of the 20th century, Arturo Toscanini and Wilhelm Furtwängler, the former never programmed Mahler’s music at all and the latter made just one recording, that of Songs of a Wayfarer with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. Mahler’s art was at the periphery of the “musical consciousness” and it was Bernstein who moved it firmly into the center, where it has remained ever since. Mahler’s centenary in 1960 was a pivotal moment: celebrating his music Bernstein initiating a yearlong festival. Soon after, in the early 1960s, he recorded all nine symphonies and the Adagio from the unfinished 10th with the New York Philharmonic. Shortly before his death in 1990 he recorded the whole cycle again. In the 1970s, all symphonies were recorded on video; eight symphonies were performed with the Vienna Philharmonic, the Second Symphony was recorded with the London Symphony and Das Lied von der Erde – with the Israel Philharmonic.

In 1960 Bernstein dedicated one of the Young People’s Concerts to Mahler; he called it “Who is Gustav Mahler?” Addressing his audience of children, many as young as eight, he talked about the special affinity he felt toward Mahler: he and Mahler were both composers and conductors, both didn’t have enough time to compose. He talked about the child’s perception of the world that, according to him constitutes the core of Mahler’s music; how his music combined the devastating pessimism with the eternal optimism. Hard to imagine that in our day somebody would talk to kids in these grownup terms. And he played Mahler’s music: from the Second symphony, and from the Fourth, and excerpts from Das Lied von der Erde. He finished that incredible concert with the performance of the last movement of the Symphony no. 4. Here it is, recorded with the same musicians who played for the kids, the New York Philharmonic, and also recorded in 1960.Permalink

August 13, 2018. Two Italians. Nicola Porpora, a prolific opera composer, was born in Naples on August 17th of 1686. He was 10 when he enrolled in the Conservatorio dei Poveri di Gesù Cristo. In 1708 he received his first opera commission but had to wait several years to get another, as the Neapolitan opera scene was dominated by Alessandro Scarlatti who had returned to Naples from Rome that year. In the meantime, Porpora was earning money at the Conservatorio di S Onofrio and giving private lessons. In 1719 Scarlatti went back to Rome and that opened the stage for Porpora. One of the operas composed during that period was Angelica, on the libretto by the young Pietro Metastasio. The role of Orlando was sung by Porpora’s star pupil, the 15-year old castrato Farinelli, who would become one of the most celebrated singers in the history of opera. Among Porpora’s pupils was also Gaetano Majorano, known as Caffarelli, also a castrato, second only to Farinelli; he became one of Handel’s favorite singers.

Cristo. In 1708 he received his first opera commission but had to wait several years to get another, as the Neapolitan opera scene was dominated by Alessandro Scarlatti who had returned to Naples from Rome that year. In the meantime, Porpora was earning money at the Conservatorio di S Onofrio and giving private lessons. In 1719 Scarlatti went back to Rome and that opened the stage for Porpora. One of the operas composed during that period was Angelica, on the libretto by the young Pietro Metastasio. The role of Orlando was sung by Porpora’s star pupil, the 15-year old castrato Farinelli, who would become one of the most celebrated singers in the history of opera. Among Porpora’s pupils was also Gaetano Majorano, known as Caffarelli, also a castrato, second only to Farinelli; he became one of Handel’s favorite singers.

In 1723-24 Porpora traveled to Vienna and Munich but received no appointments. He returned to Italy and settled in Venice. An intense rivalry developed between him and Leonardo Vinci, Porpora’s classmate in Naples. In 1730 Porpora and Vinci both produced operas which ran simultaneously in two leading Roman opera houses, one in Teatro della Dame, another – in Teatro Capranica. In 1730 Vinci died at age 40, and for a while Poprora’s competitive impulse focused on another successful opera composer, Johann Adolph Hasse.

In 1733 Porpora received an invitation from a group of Londoners who were setting up an opera company, Opera of the Nobility, to rival Handel’s Royal Academy of Music. During his three years in London Porpora composed five operas. The first, Arianna in Naxo, turned out to be the most successful one (Farinelli made his London debut in the subsequent Polifemo). Porpora left London in 1736, and less than a year later both the Opera of the Nobility and Handel’s opera house went bankrupt. Here‘s Philippe Jaroussky singing the aria Alto Giove, from Polifemo. Porpora returned to Italy, splitting his time between Venice and Naples. The opera commissions were drying up, and Porpora traveled to Dresden, where he received an appointment as Kapellmeister at the court of Saxony, which lasted for five years. In 1752 he retired and moved to Vienna. There he renewed his friendship with Metastasio; and it was probably Metastasio who introduced the 20-year old Joseph Haydn to Porpora. Haydn, who was trying to make a living as a freelancing pianist and composer, became Porpora’s valet, keyboard accompanist, and student. It seems Porpora treated Haydn badly, but nonetheless, Haydn later claimed that he learned "the true fundamentals of composition from the celebrated Herr Porpora.” In 1759 Porpora moved back to Naples. He was made maestro di cappella in the Conservatorio di S Maria di Loreto. His final opera was a failure, he had to resign from the conservatory and spent the last years of his life in poverty. Porpora died in Naples on March 3rd of 1768. At that time, our second composer, Antonio Salieri, was 17. As different as their music was, there are things that link them together: first off, Vienna, where Porpora was rather unhappy and where Salieri prospered, and also Metastasio, their mutual friend, who played important role in the lives of both.

Antonio Salieri was born on August 18th of 1750 in Legnago, Veneto. His brother, a student of Giuseppe Tartini, was Antonio’s first music teacher. Their parents died when Salieri was 14 and he ended up in Venice, the ward of a local nobleman. He was soon noticed by Florian Leopold Gassmann, a chamber composer to the Austrian Emperor Joseph II. In 1766, Gassmann brought Salieri to Vienna. Gassmann gave the youngster composition lessons and, more importantly, took him to the court to attend the evening chamber concerts. The Emperor noticed the young man; that started a relationship, which lasted till the Emperor’s death in 1790. Salieri made several other important acquaintances: one with Metastasio, another with the great composer, Christoph Willibald Gluck. Armida, Salieri’s 6th opera, was composed in 1771 when Salieri was just 21. His first big success, it was strongly influenced by Gluck. The libretto was based on a story from Torquato Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberate; it followed several illustrious operas on the same subject, such as Armide by Jean-Baptiste Lully (1686), George Frideric Handel’s Rinaldo (1711) and Armida al campo d'Egitto by Antonio Vivaldi (1718). Upon completion of Armida, Salieri wrote an even more popular La fiera di Venezia (The Fair of Venice). In 1774 the Emperor Joseph II made him the chamber composer. As the Emperor grew more interested in the spoken theater, Salieri found receptive audiences in Italy, writing operas for La Scala in Milan and theaters in Rome and Venice. In 1782, with Gluck’s help and a letter of recommendation from Joseph II, Salieri went to Paris where he picked up a commission that the very ill Gluck couldn’t fulfill. He wrote several operas while in Paris, Tarare, on a libretto by Beaumarchais, being the most successful. When Salieri returned to Vienna in 1784, he found a lot of competition, from established composers like Giovanni Paisiello to the 28-year-old Mozart. Despite his success, Salieri was entering a more challenging phase of his life.Permalink

August 6, 2018. Three French composers. Cécile Chaminade, one of the few French women composers, was born on August 8th of 1857 in Paris. Her first music lessons came from her mother, a pianist and a singer. Later she studied composition with Benjamin Godard. She started composing very young (when she was eight, she played some of her music for Georges Biset) and gained prominence with the publication of Piano Trio in 1880. An excellent pianist, she toured England many times, playing mostly her own music and became very popular there. In 1908 she went to the US, the country of “Chaminade fan clubs” and played in 12 cities, from Boston to St Louis. Between 1880 and 1890 Chaminade composed several large orchestral compositions and music for piano and orchestra. In the following period she scaled down, limiting herself to piano character pieces, of which she wrote more than 200. Many of them are charming though they became dated even during her time (Chaminade lived till 1944). Here ’s her short piano character piece, Scarf Dance. It’s performed by Lincoln Mayorga.

composing very young (when she was eight, she played some of her music for Georges Biset) and gained prominence with the publication of Piano Trio in 1880. An excellent pianist, she toured England many times, playing mostly her own music and became very popular there. In 1908 she went to the US, the country of “Chaminade fan clubs” and played in 12 cities, from Boston to St Louis. Between 1880 and 1890 Chaminade composed several large orchestral compositions and music for piano and orchestra. In the following period she scaled down, limiting herself to piano character pieces, of which she wrote more than 200. Many of them are charming though they became dated even during her time (Chaminade lived till 1944). Here ’s her short piano character piece, Scarf Dance. It’s performed by Lincoln Mayorga.

André Jolivet was also born in Paris and also on August 8th but in 1905. In his childhood he studied the cello but never went to the conservatory (he did study composition with Paul Le Fem, a composer and critic). In his youth Jolivet was influenced by Debussy and Ravel, but it all changed when he became familiar with atonal music: in December of 1927 he attended a concert at the Salle Pleyel during which several Schoenberg pieces were performed and that changed his life. Soon after he became a pupil of Edgard Varèse, an influential French-American avant-garde composer. He also befriended Olivier Messiaen, who was better known at the time and helped Jolivet by promoting his music. After the war Jolivet served as the musical director of the Comédie Française and composed a number 14 scores for plays performed at the theater. During that time, he moved away from atonality, but his music retained dissonance and rhythmic drive. He continued composing till his death in Paris, December 20th of 1974: at that time, he was working on the opera Le soldat inconnu, commissioned by the Paris Opera. Here’s his piece for flute and piano, Chant de Linos, composed in 1944. It’s performed by Emmanuel Pahud, the Principal Flute of the Berlin Philharmonic, and the pianist Eric Le Sage.

Reynaldo Hahn wasn’t French by birth but he took on French nationality later in his life, in 1909. He was born in Caracas, Venezuela, on August 9th of 1874. His father was a German-Jewish engineer, his mother came from a Spanish family. When Reynaldo, the youngest of 12 children, was four, the family moved to Paris. In 1885 Hahn entered the Paris Conservatory, where one of his teachers was Jules Massenet. At the Conservatory Hahn befriended Ravel and Cortot, and through them, many other writers and musicians. A closeted homosexual, Hahn met a young writer, Marcel Proust in 1894; they became intimate friends and lovers. Hahn is best known for his wonderful songs, here is one of them, L'enamourée. It’s sung by the soprano Anna Netrebko; the Prague Philharmonic is conducted by Emmanuel Villaume.Permalink

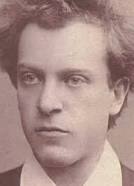

July 20, 2018. Pre-Mahlerite: the tragic story of Hans Rott. Hans Rott’s name is practically unknown these days. Usually when a composer, especially one born in modern times, is rarely performed, there’s a reason for it: it’s probably because his (and it’s almost invariably “his,” not “her”) music is not very interesting (the numerous minor Italian late-Baroque composers come to mind). We think Rott is an exception, even if we don’t expect his music to join the classical cannon any time soon. Rott’s life was both short and tragic. He was born on August 1st of 1858 in a suburb of Vienna. His father’s original name was Roth, which means that Hans was most likely Jewish, although we don’t know whether he, like Mahler some time later, had later converted to Catholicism. Rott attended the Vienna Conservatory, where his organ teacher was Anton Bruckner. His composition teacher was Franz Krenn, who also taught Mahler. Mahler, two years younger, and Rott even shared a room for a while. But it was Bruckner, and also Wagner, who influenced Rott the most. In 1878 (he was 20) Rott decided to participate in a composers’ competition, submitting the first movement of his Symphony in E Major. Everybody on the jury, except for Bruckner, was highly negative. Two years later, Rott presented the complete symphony to Brahms. He should’ve known better! Brahms intensely disliked both composers whose influence he could discern in Rott’s music: Wagner and Bruckner. Brahms’s criticism was vicious: he told Rott that he had no talent and should look for a different vocation while he was still young. We can assume that at that time Rott was already mentally ill, because just several months later while traveling to Mülhausen by train (he had reluctantly applied for and received a position of the director of the Alsatian choir association) he pointed a revolver at a fellow passenger who was trying to light a cigar. The previous encounter with Brahms was probably on his mind, as in his madness he claimed that Brahms had planted dynamite on the train and he, Rott, was just trying to save his fellow travelers from being blown up. Rott was brought back to Vienna and institutionalized. He spent the rest of his short life in a lunatic asylum. Rott died of tuberculosis on June 25th of 1884, at age 25. Here’s what Mahler said in a conversation with a friend, the violist Natalie Bauer-Lechner: “What music has lost in him is immeasurable. His first symphony, written when he was a young man of twenty, already soars to such heights of genius that it makes him – with exaggeration – the Founder of the New Symphony as I understand it. It is true that he has not yet fully realized his aims here. It is like someone taking a run for the longest possible throw and not quite hitting the mark. But I know what he is driving at. His innermost nature is so akin to mine that he and I are like two fruits from the same tree, produced by the same soil, nourished by the same air. We would have had an infinite amount in common. Perhaps we two might have gone some way together towards exhausting the possibilities of this new age that was then dawning in music.” This acknowledgement from Mahler, who started composing his own First Symphony five years after Rott completed his, is very important. Rott’s music is very Mahlerian in its sound, style, even in somewhat chaotic development. Rott stopped composing at the age of 22, consumed by insanity. In addition to his symphony, he wrote several songs, smaller orchestral pieces, a string quartet and a string quintet. We can only guess how his talents would’ve developed, but as one listens to his Symphony in E, it becomes clear that his potential was immense. Here ’s the first movement, Alla Breve; here – the second, Adagio - Sehr Langsam; here – the third, Frisch und lebhaft; and, finally, here – the fourth, Sehr langsam – Belebt. It’s performed by the Mainz State Theater Philharmonic Orchestra, Catherine Rückwardt conducting.Permalink

“her”) music is not very interesting (the numerous minor Italian late-Baroque composers come to mind). We think Rott is an exception, even if we don’t expect his music to join the classical cannon any time soon. Rott’s life was both short and tragic. He was born on August 1st of 1858 in a suburb of Vienna. His father’s original name was Roth, which means that Hans was most likely Jewish, although we don’t know whether he, like Mahler some time later, had later converted to Catholicism. Rott attended the Vienna Conservatory, where his organ teacher was Anton Bruckner. His composition teacher was Franz Krenn, who also taught Mahler. Mahler, two years younger, and Rott even shared a room for a while. But it was Bruckner, and also Wagner, who influenced Rott the most. In 1878 (he was 20) Rott decided to participate in a composers’ competition, submitting the first movement of his Symphony in E Major. Everybody on the jury, except for Bruckner, was highly negative. Two years later, Rott presented the complete symphony to Brahms. He should’ve known better! Brahms intensely disliked both composers whose influence he could discern in Rott’s music: Wagner and Bruckner. Brahms’s criticism was vicious: he told Rott that he had no talent and should look for a different vocation while he was still young. We can assume that at that time Rott was already mentally ill, because just several months later while traveling to Mülhausen by train (he had reluctantly applied for and received a position of the director of the Alsatian choir association) he pointed a revolver at a fellow passenger who was trying to light a cigar. The previous encounter with Brahms was probably on his mind, as in his madness he claimed that Brahms had planted dynamite on the train and he, Rott, was just trying to save his fellow travelers from being blown up. Rott was brought back to Vienna and institutionalized. He spent the rest of his short life in a lunatic asylum. Rott died of tuberculosis on June 25th of 1884, at age 25. Here’s what Mahler said in a conversation with a friend, the violist Natalie Bauer-Lechner: “What music has lost in him is immeasurable. His first symphony, written when he was a young man of twenty, already soars to such heights of genius that it makes him – with exaggeration – the Founder of the New Symphony as I understand it. It is true that he has not yet fully realized his aims here. It is like someone taking a run for the longest possible throw and not quite hitting the mark. But I know what he is driving at. His innermost nature is so akin to mine that he and I are like two fruits from the same tree, produced by the same soil, nourished by the same air. We would have had an infinite amount in common. Perhaps we two might have gone some way together towards exhausting the possibilities of this new age that was then dawning in music.” This acknowledgement from Mahler, who started composing his own First Symphony five years after Rott completed his, is very important. Rott’s music is very Mahlerian in its sound, style, even in somewhat chaotic development. Rott stopped composing at the age of 22, consumed by insanity. In addition to his symphony, he wrote several songs, smaller orchestral pieces, a string quartet and a string quintet. We can only guess how his talents would’ve developed, but as one listens to his Symphony in E, it becomes clear that his potential was immense. Here ’s the first movement, Alla Breve; here – the second, Adagio - Sehr Langsam; here – the third, Frisch und lebhaft; and, finally, here – the fourth, Sehr langsam – Belebt. It’s performed by the Mainz State Theater Philharmonic Orchestra, Catherine Rückwardt conducting.Permalink

July 23, 2018. Cilea, Granados, Dohnanyi, Fleisher. This week is full of anniversaries: composers, conductors, pianists and a singer. We’d like to mention (for the first time) Francesco Cilea, the Italian opera composer who was born on this day in 1866. He’s remembered for his opera Adriana Lecouvreur, written in 1902. Even back then it probably sounded rather dated, and clearly sounds so these days, but the young Enrico Caruso sung at the premier to great acclaim, and some of the arias are very beautiful. All great sopranos of the last half century have sung Adriana: Montserrat Caballé, Joan Sutherland, Maria Callas. Here’s the incomparable Renata Tebaldi in the aria Io son l'umile ancella with the Orchestra of the Accademia de Santa Cecilia under the direction of Alberto Erede (Mario del Monaco and Giulietta Simionato are also in this fabulous 1962 recording).

Cilea, the Italian opera composer who was born on this day in 1866. He’s remembered for his opera Adriana Lecouvreur, written in 1902. Even back then it probably sounded rather dated, and clearly sounds so these days, but the young Enrico Caruso sung at the premier to great acclaim, and some of the arias are very beautiful. All great sopranos of the last half century have sung Adriana: Montserrat Caballé, Joan Sutherland, Maria Callas. Here’s the incomparable Renata Tebaldi in the aria Io son l'umile ancella with the Orchestra of the Accademia de Santa Cecilia under the direction of Alberto Erede (Mario del Monaco and Giulietta Simionato are also in this fabulous 1962 recording).

We celebrate the Spanish composer Enrique Granados, who was born on July 27th of 1876, practically every year (here, for example is the entry from a year ago). So today we’ll just play his Los Requiebros, the first piece from Granados’s piano suite Goyescas. It’s performed by Jie Chen, a young Chinese-American pianist.

Ernst von Dohnányi was not as popular these pages as Granados. One reason is that as a composer he was not as interesting as some of his contemporaries. Dohnányi was, though, and under very difficult historical circumstances, a highly moral and principled person. Dohnányi, famous first as a pianist and conductor, was born on July 27th of 1877 in Bratislava, then called Pressburg in German and Pozsony in Hungarian. (His last name probably sounds familiar to many readers: he was the grandfather of the distinguished German conductor Christoph von Dohnányi). In the late 1890s he played piano concerts across Europe and the US. In the 1920s, he was appointed the head of the Budapest Academy of Music, and in that position he promoted Hungarian composers, Béla Bartók or Zoltán Kodály among them. A staunch liberal, he opposed the fascist tendencies of the Horthy aurocratic government. During WWII, he did much to save Jewish musicians, for which he was later called a “forgotten hero of the Holocaust resistance.” Dohnányi was also a noted teacher; among his pupils were the conductor Georg Solti and the pianists Annie Fischer and Georges Cziffra. Here’s a live recording of Dohnányi’s Rhapsody in C Op.11 No.3. Annie Fischer is at the piano.

Several great performers were born this week, and all we can do today is just mention them by name. The pianist Leon Fleisher was born 90 years ago today in San Francisco. His mother wanted him to become a pianist and Leon started studying the instrument at the ago of four. At the ago of 16 he played with the New York Philharmonic under Pierre Monteux, who called him “a find of the century.” Fleisher later studied with Artur Schnabel. In 1952 Fleisher won the Queen Elisabeth International Music Competition; by the late1950s he was widely recording (his recording of all five Piano Concertos by Beethoven, with the Cleveland Orchestra conducted by George Szell, was highly praised) and he was generally considered the brightest start among the new generation of American pianists. Then, in 1964, disaster struck: Fleisher lost the use of his right hand due to focal dystonia. He switched to left-hand repertory, playing, for example, left-hand concertos by Ravel and Prokofiev. After a surgery and other treatments, around 1997 Fleisher returned to two-hand repertory even thought his technique, spectacular prior to the disease, did not completely recover. Here’s Leon Fleisher playing Mozart’s Piano Sonata in C major, K.330 (1960 recording).

Riccardo Muti and Giuseppe Di Stefano were also born this week. We’ll write about them soon.Permalink

July 16, 2018. Flagstad and Stern. We missed two anniversaries last week. One was the birthday of Carl Orff, a somewhat controversial German composer, who was born on July 10th of 1895. He deserves a full entry, and that’s what we’ll do next year. Also last week was the birthday of Kirsten Flagstad: she was just two days younger than Orff, born on July 12th of 1895. The Norwegian soprano was regarded as one of the greatest, if not the greatest, Wagner singers of all time. She had a voice of phenomenal beauty, clarity and power. For the first 10 years or so of her operatic career Flagstad sang mostly lyric roles in the opera houses of Sweden and Norway. She then took on the heavier roles in Verdi’s Aida and Tosca, and, in 1932, sang the role of Isolde in Tristan und Isolde. She successfully auditioned for Winifred Wagner, Richard Wagner’s pro-Nazi daughter-in-law who ran the Bayreuth Festival, and in 1934 sang Sieglinde in Die Walküre and Gutrune in Götterdämmerung at the Bayreuth. The next year she appeared at the Metropolitan Opera, first as Sieglinde, then in the role of Isolde. Her Brünnhilde, later that same year, was a phenomenal success. An invitation from the Covent Garden followed, and there she was also received with great enthusiasm. By the end of 1936 she was world-famous. In 1941 she returned to the Nazi-occupied Norway; that chagrined some of her American listeners (her husband was accused of collaborating with the Nazis but died before his trial ended). The British were more forgiving, and Flagstad resumed her after-war career in London. She sang the difficult Wagner roles, plus Strauss and more till about 1952. By that time her tone became darker and it was harder for her to reach the top notes. She retired from the opera in 1952; fr a while she continued giving concerts, but her health began deteriorating. Flagstad died on December 7th of 1962, she was only 67 years old. Here is Kirsten Flagstad in Liebestod from Tristan und Isolde. Wilhelm Furtwangler conducts the Philharmonia Orchestra. Even though in 1952, when this recording was made, Flagstad was beyond her prime, this is a superlative live performance, both by her and by the conductor. We cannot have enough of her Isolde, so here is another live performance of Liebestod, from 1936. The recording is technically far from perfect, but Flagstad is absolutely glorious. Fritz Reiner leads the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

birthday of Kirsten Flagstad: she was just two days younger than Orff, born on July 12th of 1895. The Norwegian soprano was regarded as one of the greatest, if not the greatest, Wagner singers of all time. She had a voice of phenomenal beauty, clarity and power. For the first 10 years or so of her operatic career Flagstad sang mostly lyric roles in the opera houses of Sweden and Norway. She then took on the heavier roles in Verdi’s Aida and Tosca, and, in 1932, sang the role of Isolde in Tristan und Isolde. She successfully auditioned for Winifred Wagner, Richard Wagner’s pro-Nazi daughter-in-law who ran the Bayreuth Festival, and in 1934 sang Sieglinde in Die Walküre and Gutrune in Götterdämmerung at the Bayreuth. The next year she appeared at the Metropolitan Opera, first as Sieglinde, then in the role of Isolde. Her Brünnhilde, later that same year, was a phenomenal success. An invitation from the Covent Garden followed, and there she was also received with great enthusiasm. By the end of 1936 she was world-famous. In 1941 she returned to the Nazi-occupied Norway; that chagrined some of her American listeners (her husband was accused of collaborating with the Nazis but died before his trial ended). The British were more forgiving, and Flagstad resumed her after-war career in London. She sang the difficult Wagner roles, plus Strauss and more till about 1952. By that time her tone became darker and it was harder for her to reach the top notes. She retired from the opera in 1952; fr a while she continued giving concerts, but her health began deteriorating. Flagstad died on December 7th of 1962, she was only 67 years old. Here is Kirsten Flagstad in Liebestod from Tristan und Isolde. Wilhelm Furtwangler conducts the Philharmonia Orchestra. Even though in 1952, when this recording was made, Flagstad was beyond her prime, this is a superlative live performance, both by her and by the conductor. We cannot have enough of her Isolde, so here is another live performance of Liebestod, from 1936. The recording is technically far from perfect, but Flagstad is absolutely glorious. Fritz Reiner leads the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

The great America violinist Isaac Stern was born in Kremenetz, Ukraine, on 21 July 21st of 1920. He was 14 months old when his family emigrated to the United States. One of the greatest violinist of the 20th century and one of the most important cultural figures of his time, he deserves a full entry, and we’ll do it on an occasion. For now, here Isaac Stern and Eugene Istomin are playing Beethoven’s Sonata for Piano and Violin no. 7 Op. 30, no. 2.Permalink