Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: September 26, 2022. Schoenberg, Part III, from WWI to Nazism. We ended our previous entry on the life of Arnold Schoenbergas the world was inexorably descending into the madness of war. Schoenberg was 40 and not very healthy, as he had been suffering from asthma for years. As the war started in August of 1914, his teaching income evaporated. A patron (one Frau Lieser) offered him free board in Vienna (as it turned out, for a rather short period), where he moved later in 1914. Much of the European intelligentsia went mad with national and military fervor, denouncing the enemy and expecting their side’s win in a matter of months if not weeks. Schoenberg, unfortunately, wasn’t an exception: he supported the war against France and in a letter to Alma Mahler, Gustav’s widow, wrote: “Now we will throw these mediocre kitschmongers” (referring to the music of Stravinsky, who then lived in France, Ravel and, for some reason Bizet) “into slavery, and teach them to venerate the German spirit and to worship the German God.”

inexorably descending into the madness of war. Schoenberg was 40 and not very healthy, as he had been suffering from asthma for years. As the war started in August of 1914, his teaching income evaporated. A patron (one Frau Lieser) offered him free board in Vienna (as it turned out, for a rather short period), where he moved later in 1914. Much of the European intelligentsia went mad with national and military fervor, denouncing the enemy and expecting their side’s win in a matter of months if not weeks. Schoenberg, unfortunately, wasn’t an exception: he supported the war against France and in a letter to Alma Mahler, Gustav’s widow, wrote: “Now we will throw these mediocre kitschmongers” (referring to the music of Stravinsky, who then lived in France, Ravel and, for some reason Bizet) “into slavery, and teach them to venerate the German spirit and to worship the German God.”

During the war, Schoenberg was conscripted several times, usually being released soon after because of his ill asthma. He was composing very little; one piece he was working on for years (and never finished) was the oratorio Die Jakobsleiter (Jacob’s Ladder), the libretto for which he completed in 1915. Here’s Grand Symphonic Interlude from Die Jakobsleiter, performed by the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Kent Nagano conducting,

In Berlin, the Schoenbergs were struggling financially, and, once Frau Lieser’s generosity was over, the family had to move to cheap boarding rooms. Still, Schoenberg managed to establish a music seminar, which gained some prominence, and in time, after the war was over, the seminar grew into the Society for Private Musical Performances. The Society existed till the end of 1921, when the post-war hyperinflation wiped out much of the donor’s money. It was an amazing undertaking, which could’ve never existed today. The music, selected by Schoenberg himself, but usually not his own, was from the period “from Mahler to the present” and included, among other, works by Bartók, Busoni, Debussy, Korngold, Mahler, Ravel, Reger, Satie, Richard Strauss, Stravinsky, and Schoenberg’s students, Berg and Webern. Each work was rehearsed and often repeated in different performances; difficult pieces were sometimes repeated during the same concert. Only paying members of the Society were admitted to the concerts, but the payment was voluntary, as much as one could afford. The Society gave 117 concerts, playing 154 different works in 353 performances (so the music was repeated twice on average).

With peace in Europe, Schoenberg’s fame (and notoriety) grew. He was made president of the International Mahler League in Amsterdam and conducted many concerts across Europe. Also, in 1923 his wife Mathilde died. Even though the marriage never recovered after her 1908 romance with Richard Gerstl, Schoenberg was deeply pained. Soon after, though, he married Gertrud Kolisch, the sister of his pupil, the violinist Rudolf Kolisch (Kolisch performed at the Society’s concerts, and later, once the Society was dissolved, he founded a quartet which often played the music of Schoenberg and his students).

In 1926 Schoenberg was offered a position at the Academy of Arts in Berlin, previously occupied by the recently deceased Busoni, and he moved to Berlin for the third time. This was also a time of active artistic development, as Schoenberg transitioned from atonal music to the newly invented 12-tone system, sometimes called “serialism” (we’ll write about this another time). Here’s one of the pieces from that period, the first large-scale serial work, Variations for Orchestra, op. 31. Daniel Barenboim conducts the Chicago Symphony.

Even though the third Berlin period was mostly comfortable financially, the rising antisemitism was affecting the lives of all German Jews, Schoenberg’s included. In 1933 he resigned from the Academy of Arts, left Berlin, moved to France and soon after to the United States.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: September 19, 2022. Schoenberg, Part II, 1905 to WWI. We ended our first entry about Arnold Schoenberg around 1905. It a the time of great flourishing of the Austro-Jewish culture – think of Gustav Mahler, Zemlinsky and Erich Korngold, the writers Arthur Schnitzler, Stefan Zweig and Franz Kafka, the founder of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud and numerous other scientists, artists and intellectuals – but parallel to that, also a time of rising antisemitism: Karl Luger, for example, was the mayor of Vienna, a famous antisemite and the founder of the Christian Social Party, often viewed as a proto-Nazi organization. Schoenberg would not be able to avoid it.

the Austro-Jewish culture – think of Gustav Mahler, Zemlinsky and Erich Korngold, the writers Arthur Schnitzler, Stefan Zweig and Franz Kafka, the founder of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud and numerous other scientists, artists and intellectuals – but parallel to that, also a time of rising antisemitism: Karl Luger, for example, was the mayor of Vienna, a famous antisemite and the founder of the Christian Social Party, often viewed as a proto-Nazi organization. Schoenberg would not be able to avoid it.

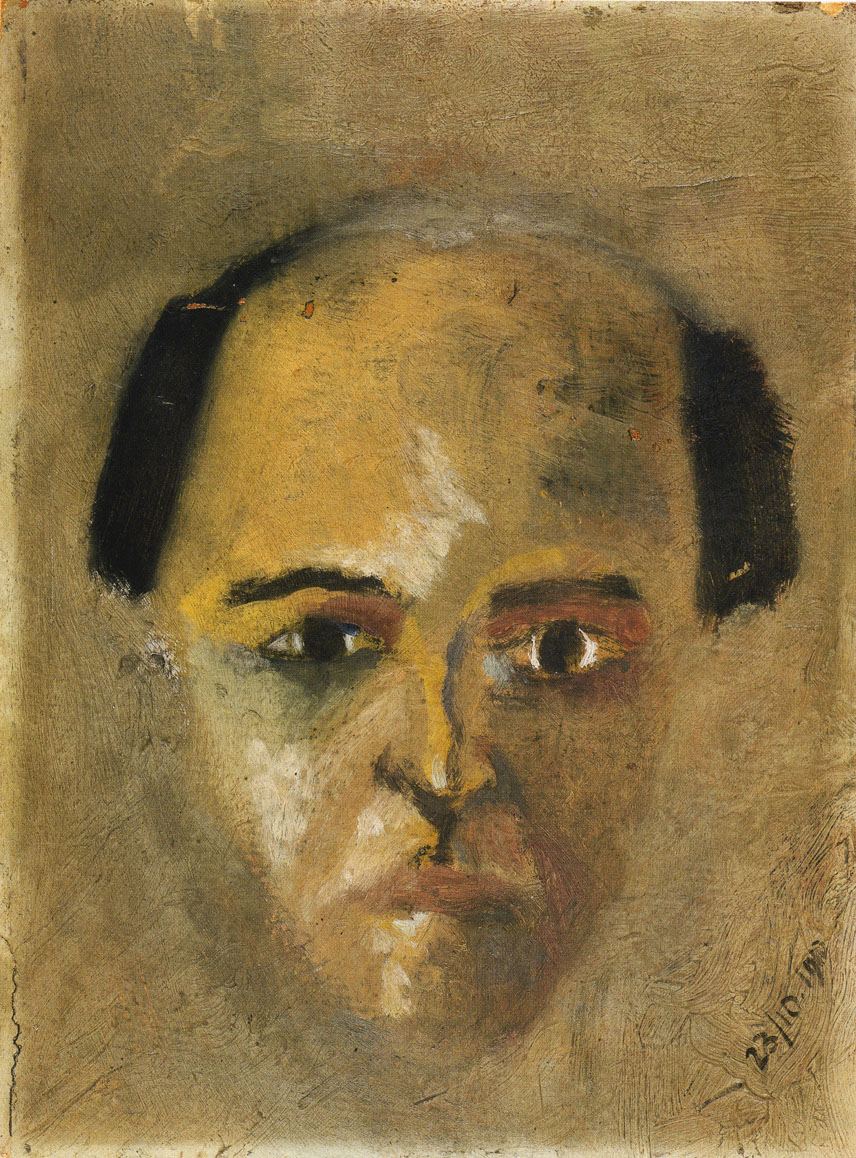

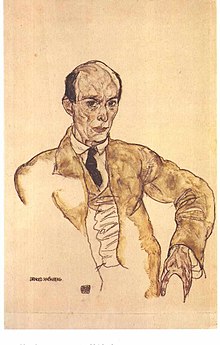

Schoenberg was struggling financially, as his teaching classes were bringing in very little money. Mahler, a staunch supporter, lent him some money, and his student, Alban Berg, collected funds on Schoenberg’s behalf. All along, his music was developing in more dissonant ways, away from tonality, and, not surprisingly, with every premiere ending in a scandal. Mahler, by the way, who believed in his talent, confessed that he didn’t understand much of Schoenberg’s music. In 1907 Mahler lost his position as the music director of the Hofoper (Vienna Imperial Opera) and that indirectly affected Schoenberg, as the influence of his supporter had waned. Here’s one of the important pieces written by Schoenberg during that period, his String Quartet no. 2 (1908). It’s performed by the young musicians of the Steans Institute. The quartet was dedicated to his wife, Mathilde, who at that time was having an affair with their friend and neighbor, artist Richard Gerstl (later that year Gerstl committed suicide; you can read more about this sordid story here). During that time Schoenberg became very interested in painting and Gerstl gave him several lessons; Schoenberg also befriended Oscar Kokoschka and Wassily Kandinsky. Schoenberg’s paintings were even displayed at exhibitions held by Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), a group founded by Kandinsky. Schoenberg’s infatuation with painting didn’t last long, even though he painted, occasionally, in his later years.

One of the largest compositions that Schoenberg wrote during that period was the one-act opera Erwartung (Expectation), Op. 17. Even though it was completed in 1909, it wasn’t premiered till 1924. In 1910 Schonberg was hired as a lecturer at the Akademie für Musik, Vienna’s largest conservatory. He hoped for a professorship, but instead was hounded out by the end of the first year by antisemitic colleagues and politicians (the Akademie was then an imperial institution and important positions were discussed in the parliament). Disappointed, Schoenberg decided to move to Berlin, which he did in the autumn of 1911.

In Berlin he returned to teaching at the Stern Conservatory, a place where he had worked eight years earlier during his first sojourn to Berlin. Many conservative music critics disapproved of his latest pieces, but, rather surprisingly, Schoenberg proved to be interesting for the public, probably due to his international notoriety; also, his earlier, Romantic music was accessible, and his new music was curious. In 1912 he composed and later that year presented Pierrot lunaire, a setting of 21 poems scored for the voice (usually soprano), flute, clarinet, violin, cello, and piano (you can listen to it here, it's performed by Lucy Shelton and Da Capo Chamber Players). Even though it was atonal, Pierrot was unexpectedly successful, and performed in eleven cities in Austria and Germany. His music even enjoyed some, rather limited, success in Vienna. In the meantime, Schoenberg came up with a new way to earn some money: even though he was never trained as a conductor, he took several lessons from Zemlinsky and went on a European tour with his own music. That was in 1914 and WWI was just days away.

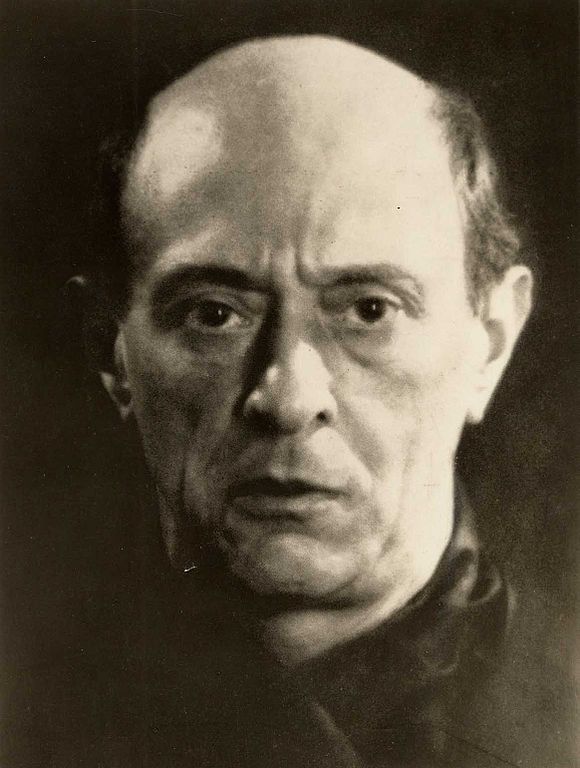

PermalinkThis Week in Classical Music: September 12, 2022. Schoenberg, Part I, the Early Years. Arnold Schoenberg, one of the most consequential composers of the 20th century, was born on September 13th in 1874. It has been some time since we last attempted to write about him, and clearly, it’s impossible to describe the life and music of such a complex figure in one entry. We’ll try to sketch part of it here and will continue at a later date.

September 13th in 1874. It has been some time since we last attempted to write about him, and clearly, it’s impossible to describe the life and music of such a complex figure in one entry. We’ll try to sketch part of it here and will continue at a later date.

Schoenberg was born in Leopoldstadt, a heavily Jewish district of Vienna. His family was lower middle class, the father a shoe-shopkeeper, the mother a piano teacher. Musically, Schoenberg was mostly self-taught: he learned to play the cello himself, and the only lessons he took were from Alexander von Zemlinsky, a friend in whose amateur orchestra Schoenberg played, while working full time as a bank clerk. Even though Zemlinksy was by then an established composer, writing in a late-Romantic style, it’s not clear how much help he provided to his student: Zemlinksy said that they mostly exchanged scores and commented on each other’s work. In 1897 Schoenberg’s quartet, edited according to Zemlinksy’s suggestions, was performed in Vienna and was well received. The following piece, the string sextet Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night), submitted by Schoenberg in 1899, was rejected by the Vienna Music Society and premiered only three years later. The piece was tonal but heavily chromatic and wondering away from the home key (you can listen to it here, played by the young students of the Steans Institute). The performance created a scandal, which would become a constant in practically all premieres of Schoenberg’s work from that point on. In the meantime, he was earning a living conducting choral societies and orchestrating operettas, a popular entertainment in Germany and Austria-Hungary. He was also composing and in 1901 completed a large cantata, Gurre-Lieder. That same year he married Zemlinsky’s sister Mathilde; later that year the couple moved to Berlin. For a while Schoenberg worked as the music director of Überbrettl, a fashionable cabaret frequented by the literati and musicians. That job ended a year later but in a lucky break, Schoenberg met Richard Strauss and showed him two pieces, Gurre-Lieder and the new symphonic poem Pelleas und Melisande. Strauss was impressed and helped Schoenberg to obtain a stipend at the Stern Conservatory, a prestigious private school which is now part of Berlin University of the Arts. He returned to Vienna in 1903.

In Vienna Schoenberg joined Zemlinky in teaching several private music classes. Some of the attendees were students of one Guido Adler. Adler is now half-forgotten, but his role in the Austro-German music world is interesting. Adler, Jewish, like Schoenberg and Zemlinksy (and Mahler), was Mahler’s friend and Bruckner’s pupil at the Vienna Conservatory. Adler practically created musicology as the scientific field we know today. He taught at the University of Vienna and the German University of Prague. One of his students was Anton Webern, who joined Schoenberg’s class. Another young composer, Alban Berg soon also joined the group. The relationship between Schoenberg and his two students, Webern and Berg, is legendary, and became central in Schoenberg’s life, as of course it was for the younger composers.

Private teaching and composing weren’t bringing much money, so, to get some funding, Schoenberg, together with Zemlinsky, managed to create a music society. Moreover, they succeeded in appointing Mahler their honorary president (Mahler had heard Verklärte Nacht a year earlier and was very impressed). The society survived for one year only but managed to present, among other piece of new music, Schoenberg’s Pelleas und Melisande. Here it is, in the performance by the Staatskapelle Berlin, Daniel Barenboim conducting.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: September 5, 2022. An overly-abundant week. Here are some of the composers born this week: one of the greatest English composers Henry Purcell; his compatriot William Boyce; Johann Christian Bach, or “the London Bach,” Johann Sebastian’s youngest son; Giacomo Meyerbeer, a Jewish-German composer who spent much of his time in France and, according to the musicologist Matthias Brzoska was “the most frequently performed opera composer during the 19th century, linking Mozart and Wagner”; Isabella Leonarda, an Italian nun and a prolific composer, a contemporary of Lully, Buxtehude, Corelli and Purcell (Purcell’s life was very short, just 36 years, whereas Leonarda lived for 84 years; she was born 39 years before Purcell and outlived him by almost nine years). Then, as we jump ahead more than a century, we meet the Czech composers Antonin Dvořák (probably the most famous of a rather small number of Czech classical composers) and soon after – the very popular Amy Beach, known as the first successful female composer of large-scale music, even though we think it’s her small-form pieces that are more interesting and inventive. Ms. Beach died in 1944, which brings us into the 20th century (Dvořák also died in the last century, 40 years earlier) and here we have one of the most unusual of avant-garde American composers, John Cage; and also Arvo Pärt, a very popular Estonian who will be 87 on September 11th.

youngest son; Giacomo Meyerbeer, a Jewish-German composer who spent much of his time in France and, according to the musicologist Matthias Brzoska was “the most frequently performed opera composer during the 19th century, linking Mozart and Wagner”; Isabella Leonarda, an Italian nun and a prolific composer, a contemporary of Lully, Buxtehude, Corelli and Purcell (Purcell’s life was very short, just 36 years, whereas Leonarda lived for 84 years; she was born 39 years before Purcell and outlived him by almost nine years). Then, as we jump ahead more than a century, we meet the Czech composers Antonin Dvořák (probably the most famous of a rather small number of Czech classical composers) and soon after – the very popular Amy Beach, known as the first successful female composer of large-scale music, even though we think it’s her small-form pieces that are more interesting and inventive. Ms. Beach died in 1944, which brings us into the 20th century (Dvořák also died in the last century, 40 years earlier) and here we have one of the most unusual of avant-garde American composers, John Cage; and also Arvo Pärt, a very popular Estonian who will be 87 on September 11th.

There are more, most not as famous as the ones listed above, and we’ll mention only two of them, Hernando de Cabezón, the son of more notable Antonio de Cabezón, a composer, music publisher and the organist to the Spanish King Philip II (Philip was also the most important patron of the great Italian painter Titian – the Prado museum in Madrid contains the greatest collection of Titians’ paintings). Also, the Danish composer Friedrich Kuhlau, familiar to many who had studied the piano and played his sonatinas.

We’d like to give you a couple of samples of the music of our composers taken from very different eras. First, Isabella Leonarda’s Magnificat, composed in 1696. It’s performed by the Italian ensemble Musica Laudantes (here). And here, from 1950, is John Cage’s String Quartet in Four Parts, recorded by the Adritti Quartet.

Two Russian pianists were also born this week, Maria Yudina and Lev Oborin, and so was the famous Hungarian violinist, Joseph Szigeti. And the mercurial soprano Angela Gheorghiu will turn 57 this week. Here is the great (and heartbreaking) final scene of Tosca with Gheorghiu and her then husband Roberto Alagna. Antonio Pappano leads the orchestra of the Covent Garden Opera in this recording from year 2000.Permalink

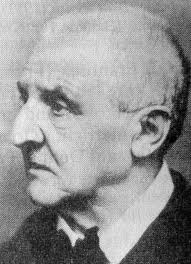

This Week in Classical Music: August 29, 2022. Bruckner and three conductors. Sometimes we write about a composer and a musician born the same week and can illustrate the music of the former as interpreted by the latter. This week we have three famous conductors, all born on the same day, but it turns out that only one of them ever recorded a symphony by our composer of the week, Anton Bruckner. It’s not very surprising that one of our conductors never played the music of Bruckner: Tullio Serafin, who was born on September 1st of 1878, was one of the greatest opera conductors of the 20th century and had a limited symphonic career. On top of that, the music of Bruckner wasn’t popular in Italy till much later in the 20th century. Serafin, born not far from Venice, studied at the Milan Conservatory and made his conducting debut in Ferrara in 1898. He became the Principal Conductor at the La Scala in 1914. His main repertoire there came from the 19th century, but he also premiered operas by Richard Strauss, Rimsky-Korsakov, Dukas and several other contemporaries. From 1924 to 1934 he worked at the Metropolitan Opera where

former as interpreted by the latter. This week we have three famous conductors, all born on the same day, but it turns out that only one of them ever recorded a symphony by our composer of the week, Anton Bruckner. It’s not very surprising that one of our conductors never played the music of Bruckner: Tullio Serafin, who was born on September 1st of 1878, was one of the greatest opera conductors of the 20th century and had a limited symphonic career. On top of that, the music of Bruckner wasn’t popular in Italy till much later in the 20th century. Serafin, born not far from Venice, studied at the Milan Conservatory and made his conducting debut in Ferrara in 1898. He became the Principal Conductor at the La Scala in 1914. His main repertoire there came from the 19th century, but he also premiered operas by Richard Strauss, Rimsky-Korsakov, Dukas and several other contemporaries. From 1924 to 1934 he worked at the Metropolitan Opera where he staged several first American productions of what’s now considered the staples of the operatic repertoire, for example, Simon Boccanegra and Turandot. In 1934 he returned to Italy and was appointed the artistic director of Teatro Reale in Rome. He remained there for nine years. After WWII he conducted the first season of the reopened La Scala.

he staged several first American productions of what’s now considered the staples of the operatic repertoire, for example, Simon Boccanegra and Turandot. In 1934 he returned to Italy and was appointed the artistic director of Teatro Reale in Rome. He remained there for nine years. After WWII he conducted the first season of the reopened La Scala.

Serafin was famous for coaching several generations of singers, from Rosa Ponselle at the Met to Magda Olivero, whom he encouraged to sing in the bel canto repertoire, at La Scala. He also worked with the three greatest sopranos of the century - Joan Sutherland, while she was at the Covent Garden, Renata Tebaldi, and Maria Callas. With Callas he made several legendary recordings, such as the 1953 Tosca (which also featured Giuseppe Di Stefano and Tito Gobbi), the 1954 Norma, Lucia di Lammermoor, recorded in 1959, and other. Serafin continued conducting into his 80s. In 1962, when he was 84, he was appointed the Artistic adviser of the Rome opera. Serafin died in Rome on February 2nd of 1968 in his 90th year.

It is much more surprising that our second conductor has never recorded a Bruckner symphony: Leonard Slatkin, who was born in 1944, also on September 1st, lead many American and European orchestras in a broad selection of works. On the other hand, he has never recorded a single Beethoven’s symphony either (we’re talking about recordings, Slatkin often conducted Beethoven in concerts, he even led a series of Beethoven festivals with the San Francisco Symphony during the late 1970s and 80s). Slatkin was born in Los Angeles, studied at the Juilliard and other schools, and started conducting in 1966. In the 1980s he made the Saint Louis Symphony into a world class orchestra. For eight years he was the music director of the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington and led the BBC Symphony orchestra for four years. From 2008 to 2018 Slatkin was the Music director of the Detroit Symphony and did much to rebuild the orchestra in the aftermath of the disastrous strike. These days Slatkin continues an active guest-conducting career although at a slower pace.

Finally (and very briefly) the conductor who did record a Bruckner: Seiji Ozawa, born on September 1st of 1935. One of the most important conductors of the last 50 years, Ozawa was sometimes criticized, especially at the end of his tenure at the Boston Symphony Orchestra. We have a special feeling for Ozawa, as we heard him conduct the Boston Symphony in the most remarkable Mahler 3rd in 1998 in Vienna’s Musikverein. Here’s the first movement of Bruckner’s Symphony no. 7. Seiji Ozawa conducts the Saito Kinen Orchestra.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: August 22, 2022. Likas Foss and Ivry Gitlis. Last week we inadvertently missed an important anniversary: the 100th birthday of the German-American composer, pianist and conductor Lukas Foss, who was born in Berlin on August 15th of 1922 (he moved to Paris in 1933 and to the US in 1937). We wrote an entry about him two years ago, so today we’ll just play some of his music. Here’s a charming Lulu’s song, from Foss’s 1953 comic opera The Jumping Frog Of Calveras County. Judith Kellock is the soprano, the composer is on the piano. And here, from 1959-60, is the first part, We’re Late, of Foss’s Time Cycle for soprano and orchestra. Adele Addison is the soprano, Leonard Bernstein leads the Columbia Symphony Orchestra. (A note about Adele Addison: she was born in New York in 1925 and is still with us, at the age of 97. Addison was educated at Princeton and later continued her studies at the Juilliard. She sang several opera roles but was better known as a recitalist and concert singer, especially in the contemporary repertoire and Baroque music. She was at her peak in 1950s and 60s, when she often sung with the New York Philharmonic under the direction of Leonard Bernstein. She later taught at the Manhattan School of Music – Dawn Upshaw was one of her students. Though not especially relevant, but Adele Addison, like Leontyne Price, Shirley Verrett, Grace Bumbry, Jessye Norman, and Maria Ewing, is black.)

composer, pianist and conductor Lukas Foss, who was born in Berlin on August 15th of 1922 (he moved to Paris in 1933 and to the US in 1937). We wrote an entry about him two years ago, so today we’ll just play some of his music. Here’s a charming Lulu’s song, from Foss’s 1953 comic opera The Jumping Frog Of Calveras County. Judith Kellock is the soprano, the composer is on the piano. And here, from 1959-60, is the first part, We’re Late, of Foss’s Time Cycle for soprano and orchestra. Adele Addison is the soprano, Leonard Bernstein leads the Columbia Symphony Orchestra. (A note about Adele Addison: she was born in New York in 1925 and is still with us, at the age of 97. Addison was educated at Princeton and later continued her studies at the Juilliard. She sang several opera roles but was better known as a recitalist and concert singer, especially in the contemporary repertoire and Baroque music. She was at her peak in 1950s and 60s, when she often sung with the New York Philharmonic under the direction of Leonard Bernstein. She later taught at the Manhattan School of Music – Dawn Upshaw was one of her students. Though not especially relevant, but Adele Addison, like Leontyne Price, Shirley Verrett, Grace Bumbry, Jessye Norman, and Maria Ewing, is black.)

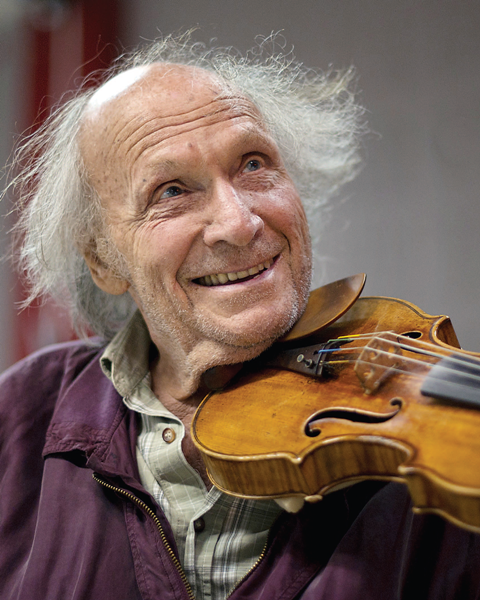

We also have another centenary: the Israeli violinist Ivry Gitlis was born on August 22nd of 1922 in Haifa. His parents had emigrated from Kamianets-Podilskyi in western Ukraine the previous year. Ivry took up the violin at the age of five, and at the age of eight played to Bronisław Huberman, the famous Polish violinist who was visiting Palestine (several years later, in 1936, Huberman founded Israel’s first symphony orchestra, the Palestine Symphony Orchestra, now called Israel Philharmonic). Huberman was impressed and organized a fundraiser to send Ivry to France for further studies. In Paris Gitlis went to the Conservatoire where his teachers were George Enescu and Jacques Thibaud. During WWII Gitlis moved to the UK (which probably saved his life) and performed many concerts for the troops. In the 1950s he traveled to the US, where he met Jascha Heifetz and, under the management of Sol Hurok, established himself as one of the premier violinists. Later in the 1950s he returned to France.

in Haifa. His parents had emigrated from Kamianets-Podilskyi in western Ukraine the previous year. Ivry took up the violin at the age of five, and at the age of eight played to Bronisław Huberman, the famous Polish violinist who was visiting Palestine (several years later, in 1936, Huberman founded Israel’s first symphony orchestra, the Palestine Symphony Orchestra, now called Israel Philharmonic). Huberman was impressed and organized a fundraiser to send Ivry to France for further studies. In Paris Gitlis went to the Conservatoire where his teachers were George Enescu and Jacques Thibaud. During WWII Gitlis moved to the UK (which probably saved his life) and performed many concerts for the troops. In the 1950s he traveled to the US, where he met Jascha Heifetz and, under the management of Sol Hurok, established himself as one of the premier violinists. Later in the 1950s he returned to France.

Even though Gitlis played a wide contemporary repertoire (and had many pieces written for him), he was rather old-fashioned when playing the Romantics. You can hear it in this interpretation of César Franck’s Violin sonata which he played in 1998 with none other than Martha Argerich (this is a live recording). Gitlis was then 78. He died in Paris on December 24th of 2020 at the age of 98.

Several composers were born this week, Ernst Krenek, Leonard Bernstein and Karlheinz Stockhausen among them. Claude Debussy, who was born on this day in 1862, 160 years ago has a special place in our heart. Check out our library, it has about 250 recordings of Debussy’s works, so if you wish to celebrate him today, browse it and find something to your liking. It’s very much worth it.Permalink