Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

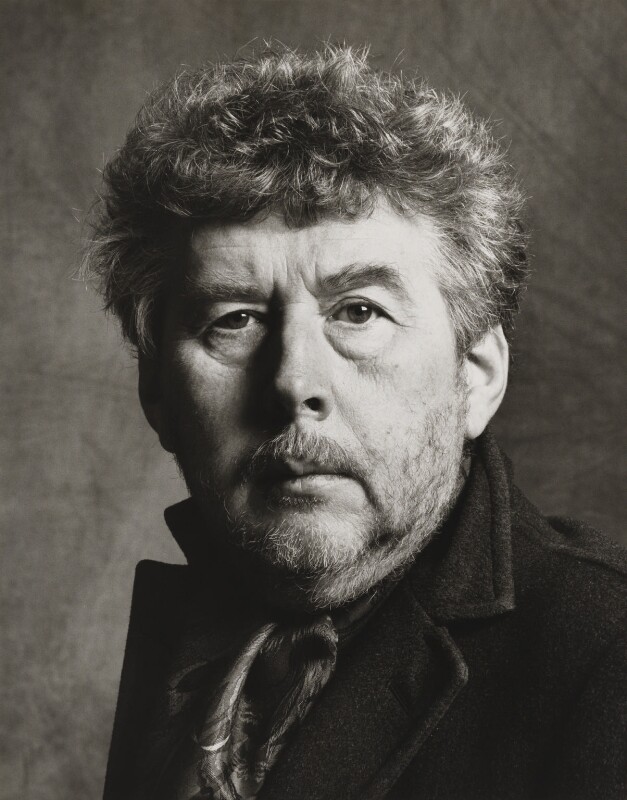

This Week in Classical Music: July 11, 2022. Birtwistle and Bergonzi. One of the best-known British modern classical composers, Harrison Birtwistle, was born on July 15th of 1934 not far from Manchester (Birtwistle died less than three months ago at the age of 87). His music was thoroughly modern, sometimes evocative of Stravinsky and Messiaen, other times more formal, following Boulez and Stockhausen. In any event, it was very different from the music of the preceding generations of British composers, from Frederick Delius and Ralph Vaughan Williams to Benjamin Britten, although, like Britten, Birtwistle had written a number of operas (seven, to be exact).

from Manchester (Birtwistle died less than three months ago at the age of 87). His music was thoroughly modern, sometimes evocative of Stravinsky and Messiaen, other times more formal, following Boulez and Stockhausen. In any event, it was very different from the music of the preceding generations of British composers, from Frederick Delius and Ralph Vaughan Williams to Benjamin Britten, although, like Britten, Birtwistle had written a number of operas (seven, to be exact).

The Triumph of Time is one of Harrison Birtwistle’s better known orchestral compositions. It was written in 1971-72. The title came from a complex (and quite macabre) 1574 woodcut by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, which Birtwistle stumbled upon while working on the composition. You can see it here in good resolution. In the woodcut the Time, a muscular middle-aged man, is in a carriage drawn by horses representing Sun and Moon. He’s followed by Death. Part of Bruegel’s inscription at the bottom of the carving says: “All that Time cannot grasp is left for Death,” but Time itself is devouring a child. Birtwistle’s work is far from being literal or macabre, but it is funerial in its overall tone. Birtwistle said of the piece that it’s "a processional in which nothing changes.” Whether it changes or not (and it does), the piece is fascinating and anything but dull, one reason being Birtwistle’s virtuosic use of multiple percussion. You can listen to The Triumph of Time here; it’s performed live by the BBC Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Peter Eötvös.

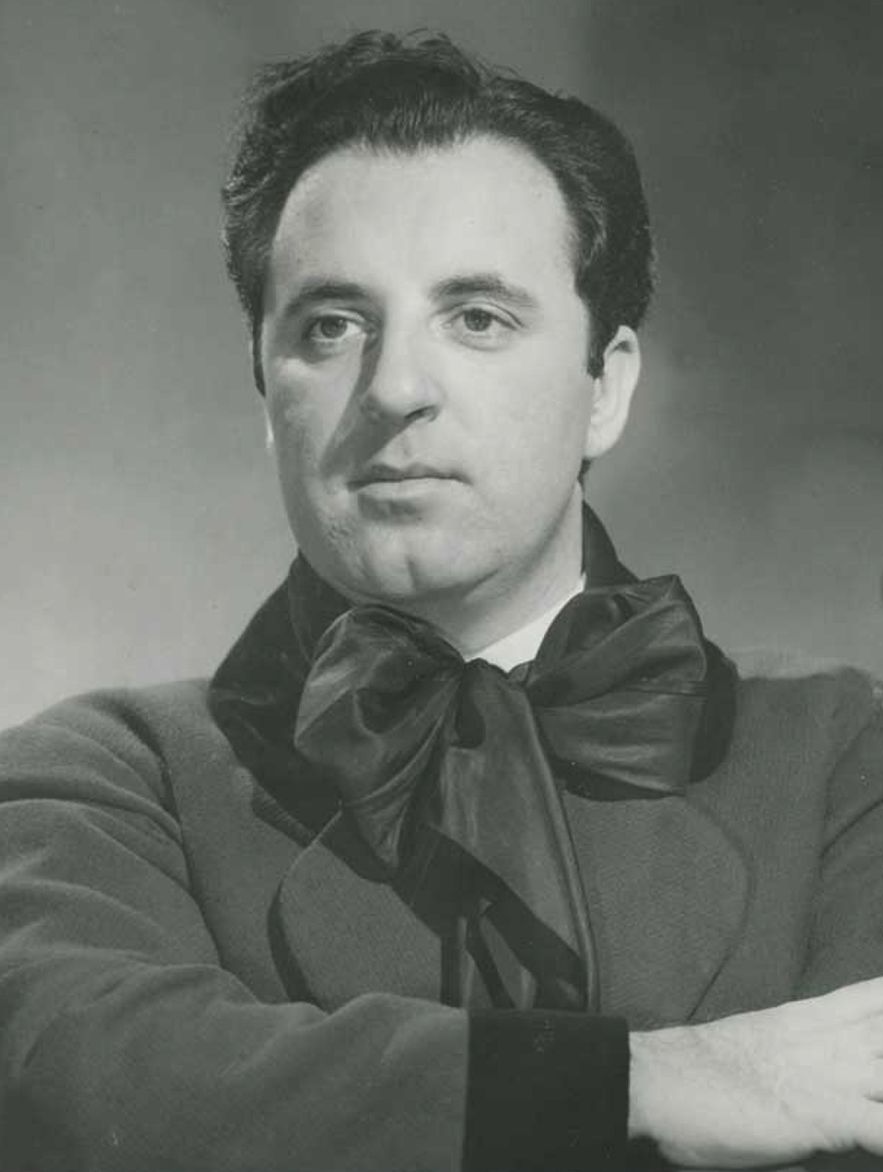

Carlo Bergonzi, born on July 13th of 1924, was one of the greatest tenors of the mid-20th century and would’ve been even more famous had he not been a contemporary of Franco Corelli, Giuseppe di Stefano and Mario Del Monaco. What a time it was, when all of them were at the top of their careers in the 1960s! Add to the four Italians - a Spaniard, Alfredo Kraus, and compare these magnificent singers with the tenors of today…

Giuseppe di Stefano and Mario Del Monaco. What a time it was, when all of them were at the top of their careers in the 1960s! Add to the four Italians - a Spaniard, Alfredo Kraus, and compare these magnificent singers with the tenors of today…

Bergonzi started as a baritone (as, by the way, did Placido Domingo) and made his debut in a baritone role as Rossini’s Figaro in 1948. For the following three years he sung many challenging baritone roles, including Silvio in Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci, Lescaut in Puccini’s Manon Lescaut, and Rigoletto. Then in 1951 he realized that his voice is naturally better suited for tenor roles and, after retraining and studying the tenor repertory he made a second debut, this time as a tenor in the title role of Andrea Chénier. He made his La Scala debut in 1953 and went on to sing at the famed opera theater for the next 20 years. He first sang in the US in 1955, in Chicago, and a year later debuted at the Met, where he regularly appeared for the next 30 years, till 1988.

Bergonzi sang in more than 40 roles, Verdi’s operas constituting the core of his repertory. Here is the famous Celeste Aida from Act I of Verdi’s Aida in Bergonzi’s superb rendition. Nello Santi conducts the New Philharmonia Orchestra.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: July 4, 2022. Mahler. Gustav Mahler was born this week, on July 7th of 1860. We freely admit that for us Mahler remains one of the most important and beloved composers and that he has been so for a long time. This is rather unusual, as other composers of genius (and there were many in the last several hundred years) drift in and out, becoming more important and then receding somewhat as tastes change and other music periods come to the fore (take, for example, the overwhelmingly Romantic piano repertoire of the mid-20th century, now being performed sparingly). To think of it, this is unusual for a composer who wrote just nine full symphonies, part of a tenth, a symphony/song cycle (Das Lied von der Erde), and several other song cycles – that’s practically it. All of Mahler’s music could be played in less than 20 hours. Compare it with Beethoven’s output (nine symphonies, five piano concertos, plus 32 piano sonatas, a violin concerto, nine violin sonatas, a full-length opera, 17 string quartets and much more) or Bach’s, with more than 200 cantatas alone, plus Passions, oratorios, concertos, and numerous other pieces for individual instruments and ensembles. During the last century, Mahler also played a significant extra-musical role, serving as a litmus test in the ongoing culture wars, starting with the Nazis and all the way to our time (we’ll come back to this issue later).

beloved composers and that he has been so for a long time. This is rather unusual, as other composers of genius (and there were many in the last several hundred years) drift in and out, becoming more important and then receding somewhat as tastes change and other music periods come to the fore (take, for example, the overwhelmingly Romantic piano repertoire of the mid-20th century, now being performed sparingly). To think of it, this is unusual for a composer who wrote just nine full symphonies, part of a tenth, a symphony/song cycle (Das Lied von der Erde), and several other song cycles – that’s practically it. All of Mahler’s music could be played in less than 20 hours. Compare it with Beethoven’s output (nine symphonies, five piano concertos, plus 32 piano sonatas, a violin concerto, nine violin sonatas, a full-length opera, 17 string quartets and much more) or Bach’s, with more than 200 cantatas alone, plus Passions, oratorios, concertos, and numerous other pieces for individual instruments and ensembles. During the last century, Mahler also played a significant extra-musical role, serving as a litmus test in the ongoing culture wars, starting with the Nazis and all the way to our time (we’ll come back to this issue later).

For several years we’ve been traversing Mahler’s life using his symphonies as guideposts. A couple of years ago we finished our entry about the Seventh symphony writing, “The years 1904 – 1905 were good to Mahler. He was acknowledged as a great opera conductor, and his symphonic programs with the Philharmonic were popular. Some of his compositions even had critical and popular success (Symphony no. 7 would not go on to be one of them). He lived very comfortably, was happily married, and his second daughter, Anna, was born in 1904. He had many friends and admirers among musicians and developed a special relationship with the Concertgebouw Orchestra and its conductor Willem Mengelberg. Just three years later Mahler would have to leave Hofoper, hounded by antisemitic music critics; in 1907 his first daughter, Maria, would die of scarlet fever and his marriage to Alma would be on the rocks.”

Mahler composed most of his Eighth symphony in the summer of 1906, at the end of his “happy period,” not, of course, that he was aware of it and of what was to come. His Sixth symphony was premiered in May of that year in Essen, with Mahler conducting, and in June he took his family to Maiernigg in Carinthia, where he had a villa overlooking the Wörthersee (lake Wörth). He had been going to Maiernigg since 1900 and in 1901 had a “composing hut” built there, to which he would retreat, alone, to write and contemplate. That’s where he composed all of his symphonies from the Forth to the Eighth. The latter was written very quickly, in just two months, though some changes were made later. The Eighth was called “Symphony of a Thousand” by its original promoter, Emil Gutmann, as it required a huge orchestra, vocal soloists, two regular choirs and one children’s choir (the real number of performers was smaller than one thousand and Mahler disapproved of the moniker). The symphony consists of two parts rather than the usual several movements - a relatively short Part One, based on the traditional Latin text of the hymn Veni Creator Spiritus, and Part Two, which runs about an hour or more, depending on the conductor, and is based on the closing scene of Goethe's Faust.

The Eighth was premiered in Munich on September 12th of 1910. It was the last time that Mahler would conduct a premier of his symphony. Emil Gutmann promoted it heavily and the public’s anticipation was enormous. Here are just some of the cultural figures in attendance: composers Richard Strauss, Camille Saint-Saëns and Anton Webern; the leading writers of Germany, Thomas Mann, and Austria, Arthur Schnitzler; and Leopold Stokowski, who would conduct the American premier of the symphony several years later. The performance was an unqualified success, which is rather surprising, considering that a more accessible Sixth symphony was received coolly. Thomas Mann sent Mahler an effusive congratulatory letter and later gave the writer Gustav von Aschenbach, the protagonist of his novella Death in Venice the “Mask of Mahler.” Some year later the great Italian director Luchino Visconti took it a step further and made Aschenbach into a composer and used the Adagietto from Mahler’s Fifth symphony as the movie’s main theme, popularizing it for years to come.

We’ll hear the famous 1972 recording of the symphony made by Sir Georg Solti conducting the Vienna Boys Choir, the Choir of the Vienna Musikverein, the Choir of the Vienna State Opera, the Chicago Symphony, and several vocalists, among them the soprano Lucia Popp, the tenor René Kollo and the bass Martti Talvela. Part 1 is here, part 2 – here.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: July 4, 2022. Mahler. Gustav Mahler was born this week, on July 7th of 1860. We freely admit that for us Mahler remains one of the most important and beloved composers and that he has been so for a long time. This is rather unusual, as other composers of genius (and there were many in the last several hundred years) drift in and out, becoming more important and then receding somewhat as tastes change and other music periods come to the fore (take, for example, the overwhelmingly Romantic piano repertoire of the mid-20th century, now being performed sparingly). To think of it, this is unusual for a composer who wrote just nine full symphonies, part of a tenth, a symphony/song cycle (Das Lied von der Erde), and several other song cycles – that’s practically it. All of Mahler’s music could be played in less than 20 hours. Compare it with Beethoven’s output (nine symphonies, five piano concertos, plus 32 piano sonatas, a violin concerto, nine violin sonatas, a full-length opera, 17 string quartets and much more) or Bach’s, with more than 200 cantatas alone, plus Passions, oratorios, concertos, and numerous other pieces for individual instruments and ensembles. During the last century, Mahler also played a significant extra-musical role, serving as a litmus test in the ongoing culture wars, starting with the Nazis and all the way to our time (we’ll come back to this issue later).

beloved composers and that he has been so for a long time. This is rather unusual, as other composers of genius (and there were many in the last several hundred years) drift in and out, becoming more important and then receding somewhat as tastes change and other music periods come to the fore (take, for example, the overwhelmingly Romantic piano repertoire of the mid-20th century, now being performed sparingly). To think of it, this is unusual for a composer who wrote just nine full symphonies, part of a tenth, a symphony/song cycle (Das Lied von der Erde), and several other song cycles – that’s practically it. All of Mahler’s music could be played in less than 20 hours. Compare it with Beethoven’s output (nine symphonies, five piano concertos, plus 32 piano sonatas, a violin concerto, nine violin sonatas, a full-length opera, 17 string quartets and much more) or Bach’s, with more than 200 cantatas alone, plus Passions, oratorios, concertos, and numerous other pieces for individual instruments and ensembles. During the last century, Mahler also played a significant extra-musical role, serving as a litmus test in the ongoing culture wars, starting with the Nazis and all the way to our time (we’ll come back to this issue later).

For several years we’ve been traversing Mahler’s life using his symphonies as guideposts. A couple of years ago we finished our entry about the Seventh symphony writing, “The years 1904 – 1905 were good to Mahler. He was acknowledged as a great opera conductor, and his symphonic programs with the Philharmonic were popular. Some of his compositions even had critical and popular success (Symphony no. 7 would not go on to be one of them). He lived very comfortably, was happily married, and his second daughter, Anna, was born in 1904. He had many friends and admirers among musicians and developed a special relationship with the Concertgebouw Orchestra and its conductor Willem Mengelberg. Just three years later Mahler would have to leave Hofoper, hounded by antisemitic music critics; in 1907 his first daughter, Maria, would die of scarlet fever and his marriage to Alma would be on the rocks.”

Mahler composed most of his Eighth symphony in the summer of 1906, at the end of his “happy period,” not, of course, that he was aware of it and of what was to come. His Sixth symphony was premiered in May of that year in Essen, with Mahler conducting, and in June he took his family to Maiernigg in Carinthia, where he had a villa overlooking the Wörthersee (lake Wörth). He had been going to Maiernigg since 1900 and in 1901 had a “composing hut” built there, to which he would retreat, alone, to write and contemplate. That’s where he composed all of his symphonies from the Forth to the Eighth. The latter was written very quickly, in just two months, though some changes were made later. The Eighth was called “Symphony of a Thousand” by its original promoter, Emil Gutmann, as it required a huge orchestra, vocal soloists, two regular choirs and one children’s choir (the real number of performers was smaller than one thousand and Mahler disapproved of the moniker). The symphony consists of two parts rather than the usual several movements - a relatively short Part One, based on the traditional Latin text of the hymn Veni Creator Spiritus, and Part Two, which runs about an hour or more, depending on the conductor, and is based on the closing scene of Goethe's Faust.

The Eighth was premiered in Munich on September 12th of 1910. It was the last time that Mahler would conduct a premier of his symphony. Emil Gutmann promoted it heavily and the public’s anticipation was enormous. Here are just some of the cultural figures in attendance: composers Richard Strauss, Camille Saint-Saëns and Anton Webern; the leading writers of Germany, Thomas Mann, and Austria, Arthur Schnitzler; and Leopold Stokowski, who would conduct the American premier of the symphony several years later. The performance was an unqualified success, which is rather surprising, considering that a more accessible Sixth symphony was received coolly. Thomas Mann sent Mahler an effusive congratulatory letter and later gave the writer Gustav von Aschenbach, the protagonist of his novella Death in Venice the “Mask of Mahler.” Some year later the great Italian director Luchino Visconti took it a step further and made Aschenbach into a composer and used the Adagietto from Mahler’s Fifth symphony as the movie’s main theme, popularizing it for years to come.

We’ll hear the famous 1972 recording of the symphony made by Sir Georg Solti conducting the Vienna Boys Choir, the Choir of the Vienna Musikverein, the Choir of the Vienna State Opera, the Chicago Symphony, and several vocalists, among them the soprano Lucia Popp, the tenor René Kollo and the bass Martti Talvela. Part 1 is here, part 2 – here.Permalink

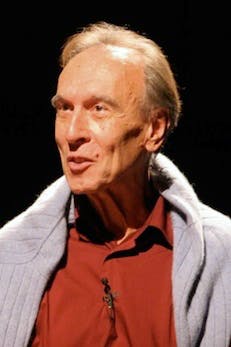

This Week in Classical Music: June 27, 2022. Three Conductors. We’re not going to ignore the three composers that were born this week, Christoph Willibald Gluck (on July 2nd of 1714), Leoš Janáček (on July 3rd of 1854) and Hans Werner Henze (July 1st of 1926), but would rather refer to the entry of two years ago where we wrote about all three. Instead, we’ll write about another three conductors whose birthdays are also celebrated this week: Claudio Abbado, born June 26th of 1933 in Milan; the Czech conductor Rafael Kubelík, who born on June 29th, 1914, one day after Archduke Ferdinand's assassination, as a result of which his country, Bohemia, then part of Austria-Hungary, became Czechoslovakia; and Carlos Kleiber, born July 3rd of 1930. We must confess that of these three we especially love Abbado, even though all three are considered among the best in the last century, and many think that Carlos Kleiber was the greatest.

one day after Archduke Ferdinand's assassination, as a result of which his country, Bohemia, then part of Austria-Hungary, became Czechoslovakia; and Carlos Kleiber, born July 3rd of 1930. We must confess that of these three we especially love Abbado, even though all three are considered among the best in the last century, and many think that Carlos Kleiber was the greatest.

During his life Abbado led, as Music director, several major orchestras, starting with the orchestra of the La Scala, then Vienna Philharmonic, London Symphony Orchestra, the Chicago Symphony (as the Principal guest conductor), and finally, the Berlin Philharmonic, which he headed from 1990 to 2002. His tenure there was interrupted by a diagnosis of stomach cancer, but he returned to Berlin several times from 2006 to 2014. He also founded two orchestras, the European Union Youth Orchestra and the Gustav Mahler Jugendorchester. While Abbado was a major champion of the music of 20th century composers (for example, he recorded many of Henze’s works for Deutsche Grammophon), he was also a great interpreter of the traditional classical repertoire, from Mozart and Beethoven to Mahler (of whose music we think he was one of the greatest interpreters). Abbado was also a major opera conductor, having worked at La Scala, the Vienna Staatsoper, Metropolitan Opera, and London’s Covent Garden.

The Wikipedia entry for Carlos Kleiber states directly that “[he] was an Austrian conductor who is widely regarded as among the greatest conductors of all time,” and refers to the 2015 poll conducted by BBC Music Magazine among 100 top conductors working today (in the same poll, Abbado was placed third, after Leonard Bernstein). Kleiber, baptized Karl, was born in Berlin, the son of a renowned conductor, Erich Kleiber. In 1935 the family emigrated to Argentina, and Karl was renamed Carlos. He studied music as a kid in Argentina and Chile, then chemistry in Zurich. He worked his way starting as a repetiteur in Munich, eventually making his conducting debut in 1954. He then worked at the opera theaters of Düsseldorf, Zurich and Stuttgart. In the 1970s he became acknowledged as one of the finest young conductors, working in the Vienna Staatsoper, at Bayreuth, in Covent Garden and La Scala. He led the best orchestras, including the Chicago Symphony, London Symphony, and the Berlin Philharmonic. He was the first choice of the Berlin Phil to succeed Karajan, but declined the offer after which the position went to Claudio Abbado.

is widely regarded as among the greatest conductors of all time,” and refers to the 2015 poll conducted by BBC Music Magazine among 100 top conductors working today (in the same poll, Abbado was placed third, after Leonard Bernstein). Kleiber, baptized Karl, was born in Berlin, the son of a renowned conductor, Erich Kleiber. In 1935 the family emigrated to Argentina, and Karl was renamed Carlos. He studied music as a kid in Argentina and Chile, then chemistry in Zurich. He worked his way starting as a repetiteur in Munich, eventually making his conducting debut in 1954. He then worked at the opera theaters of Düsseldorf, Zurich and Stuttgart. In the 1970s he became acknowledged as one of the finest young conductors, working in the Vienna Staatsoper, at Bayreuth, in Covent Garden and La Scala. He led the best orchestras, including the Chicago Symphony, London Symphony, and the Berlin Philharmonic. He was the first choice of the Berlin Phil to succeed Karajan, but declined the offer after which the position went to Claudio Abbado.

Kleiber was famous for rehearsing extensively, almost obsessively (it’s said that he had 34 rehearsals of his first performance of Berg’s Wozzeck) and also for canceling many performances: in his almost 50-year career he conducted just 90 orchestral concerts and 620 opera performances. Kleiber knew six languages (English, Spanish, German, French, Italian and Slovenian) but never gave a single formal interview (he never had a professional music agent either). His formal discography is small: it consists of several symphonies by Beethoven, Brahms and Schubert and several operas, though after his death a number of pirated live recordings have been published.

We thought it would be interesting to present the same symphony conducted by Abbado and Kleiber, both with excellent orchestras. One piece we could find that both had recorded was Brahms’s Symphony no. 4. Here’s Abbado and Berlin Philharmonic in the 1991 recording. And here’s Carlos Kleiber conducting the Vienna Philharmonic. This recording was made in March of 1980. And we promise to write about Rafael Kubelík another time.Permalink

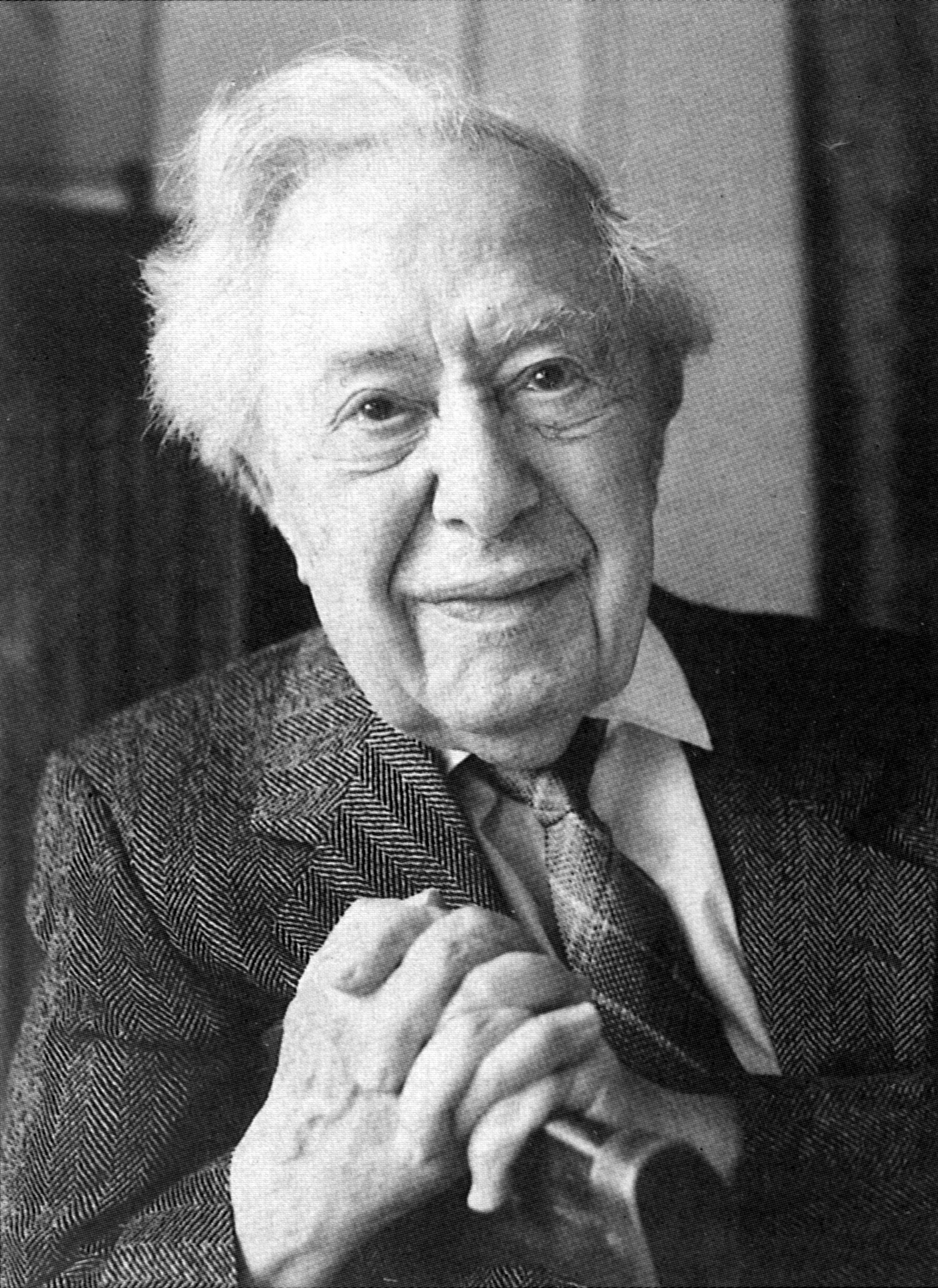

This Week in Classical Music: June 20, 2022. A Horszowski encounter. Langhe is an exceptionally beautiful part of Italy, a stretch of hilly land south of Turin famous for its Barolo and Barbaresco wines and white truffles. It’s dotted with hilltop villages and castles and reminds one of much more popular (and crowded) Tuscany. The area around the village of Barolo is particularly pretty, with 12th-century castles facing each other across the vineyard-covered valleys. Monforte d'Alba is about two and a half miles from Barolo as the crow flies and twice as much to drive (which is a pleasure to do, so delightful are the ever-changing vistas), it has the requisite castle and a church at the top of the hill. It also has an unusual Roman-style open theater next to it, pictured here. What is completely unexpected, though, is to see the name of the pianist Mieczysław Horszowski: it’s right there on a plaque which says: “Auditorium Miecio Horszowski “Nostro piccolo gran consolatore”(our little great comforter),” and dated 1986. “Miecio” is probably the best Italians could do with the name Mieczysław, “Piccolo” clearly refers to Horszowski’s stature – he was about five feet tall, but Gran (short for Grande) indicates his status as a musician and cultural figure.

and Barbaresco wines and white truffles. It’s dotted with hilltop villages and castles and reminds one of much more popular (and crowded) Tuscany. The area around the village of Barolo is particularly pretty, with 12th-century castles facing each other across the vineyard-covered valleys. Monforte d'Alba is about two and a half miles from Barolo as the crow flies and twice as much to drive (which is a pleasure to do, so delightful are the ever-changing vistas), it has the requisite castle and a church at the top of the hill. It also has an unusual Roman-style open theater next to it, pictured here. What is completely unexpected, though, is to see the name of the pianist Mieczysław Horszowski: it’s right there on a plaque which says: “Auditorium Miecio Horszowski “Nostro piccolo gran consolatore”(our little great comforter),” and dated 1986. “Miecio” is probably the best Italians could do with the name Mieczysław, “Piccolo” clearly refers to Horszowski’s stature – he was about five feet tall, but Gran (short for Grande) indicates his status as a musician and cultural figure.

Mieczysław Horszowski, a wonderful Polish-Russian-Jewish-American pianist is famous for his art and his longevity, both artistic and physical: he played his last concert at the age of 99 and died one month short of his 101st birthday. We don’t know the details of his association with the auditorium, but Horszowski did live in Milan for 25 years, which is less than a two-hour drive away. Also, when Horszowski was 89, he married the Italian pianist Bice Costa, thirty plus his younger. It’s our guess that this may’ve been the connection, but what we do know for sure is that Horszowski played at the inaugural concert and the venue was later named after him, Auditorium Horszowski. A jazz festival takes place there every year.

Mieczysław Horszowski was born in Lemberg, Austria-Hungary (now Lviv, Ukraine) on June 23rd of 1892. He became Theodor Leschetizky’s student at the age of seven and played Beethoven’s Piano concerto no. 1 in Warsaw at the age of eight. In 1906 he made his American debut, playing at the Carnegie Hall. Since 1914 till the outbreak of WWII he lived in Milan and then moved to the United States where he joined the staff of the Curtis Institute (among his students were Murray Perahia, and Richard Goode). Despite his small hands, Horszowski had a fabulous technique, and his favorite repertoire – works by Bach, Beethoven and Chopin – didn’t require huge hands. As many of Leschetizky’s pupils (we can think of Artur Schnabel, Benno Moiseiwitsch, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Ignaz Friedman), Horszowski had a beautiful singing sound. For 50 years he partnered with his friend Pablo Casals, who preferred Horszowski to any other pianist.

23rd of 1892. He became Theodor Leschetizky’s student at the age of seven and played Beethoven’s Piano concerto no. 1 in Warsaw at the age of eight. In 1906 he made his American debut, playing at the Carnegie Hall. Since 1914 till the outbreak of WWII he lived in Milan and then moved to the United States where he joined the staff of the Curtis Institute (among his students were Murray Perahia, and Richard Goode). Despite his small hands, Horszowski had a fabulous technique, and his favorite repertoire – works by Bach, Beethoven and Chopin – didn’t require huge hands. As many of Leschetizky’s pupils (we can think of Artur Schnabel, Benno Moiseiwitsch, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Ignaz Friedman), Horszowski had a beautiful singing sound. For 50 years he partnered with his friend Pablo Casals, who preferred Horszowski to any other pianist.

Here's Bach’s Partita No. 2 in C minor, recorded live in 1983. This live recording was made in Italy, but not in Monforte d'Alba but in a church of a Tuscan village of Castagno d'Andrea.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: June 13, 2022. Stravinsky. On June 17th we’ll celebrate Igor Stravinsky’s 140th anniversary: he was born on that day in 1882 in Oranienbaum, a small town outside of Russia’s capital, Saint Petersburg. After 1910 Stravinsky spent much of his time in France and Switzerland, and in 1918, soon after the Russian Revolution, he left the country for good. We just visited Montreux, Switzerland; in 1910 Stravinsky lived in Clarens, which is one of Montreux’s neighborhoods, and that’s where his second son, Soulima, was born. (This area is rich in Russian cultural connections: in 1878 Tchaikovsky stayed in Clarens as he was recovering from depression after his disastrous marriage to Antonina Miliukova; he wrote his Violin Concerto there. Vladimir Nabokov lived the last 16 years of his life in Montreux and is buried in Clarens). Stravinsky returned to Clarens in 1914 and a year later moved to Morges, another town on the shores of Lake Geneva. Montreux remembers Stravinsky: there’s a statue of the composer in the city, and one of the major auditoriums is named after him.

outside of Russia’s capital, Saint Petersburg. After 1910 Stravinsky spent much of his time in France and Switzerland, and in 1918, soon after the Russian Revolution, he left the country for good. We just visited Montreux, Switzerland; in 1910 Stravinsky lived in Clarens, which is one of Montreux’s neighborhoods, and that’s where his second son, Soulima, was born. (This area is rich in Russian cultural connections: in 1878 Tchaikovsky stayed in Clarens as he was recovering from depression after his disastrous marriage to Antonina Miliukova; he wrote his Violin Concerto there. Vladimir Nabokov lived the last 16 years of his life in Montreux and is buried in Clarens). Stravinsky returned to Clarens in 1914 and a year later moved to Morges, another town on the shores of Lake Geneva. Montreux remembers Stravinsky: there’s a statue of the composer in the city, and one of the major auditoriums is named after him.

This period was tremendously productive for Stravinsky: he wrote ballets Petruska and The Rite of Spring for Diagilev’s famous dance company, the Ballets Russes, and The Nightingale, an opera-ballet, also premiered by Diagilev’s Ballets Russes at the Palais Garnier in Paris in 1914. For this production, the Russian painter Alexandre Benois designed the sets and costumes (one of Diagilev geniuses was his ability to bring together the best composers and painters to work on his productions). In 1917, Stravinsky wrote The Song of the Nightingale, a symphonic poem based on the opera. Here it is, performed by the Seattle Symphony Orchestra, Gerard Schwarz conducting.Permalink