Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: February 14, 2022. Kurtág and more. This week brings a bevy of musical talents from several centuries, from Michael Praetoriuswho was born in 1571, probably on February 15th (although some musicologist think he might have been born on September 28th of that year) toFrancesco Cavalli, who was born on this day in 1602, to Arcangelo Corelli, born half a century later, on February 17th of 1653, and then, skipping several well-known names, to the Hungarian composer . It was Kurtág’s name that caught our eye: in five days he will turn 96! But of course it’s not the longevity that makes him special (after all, Elliott Carter lived much longer, to the age of 103): Kurtág is one of the most interesting composers of the 20th century. Here’s an interesting question to ponder: in 100 years, assuming that classical music survives that long as a genre, who would be more popular, Corelli or Kurtág? We think that Kurtág is a much more original composer, but will music lovers internalize and accept the complexities of his music (obviously this is not the case yet). As long as we ventured into the shaky grounds of comparisons, we might as well say that we think that Cavalli was more interesting than Corelli, except for the genre of the early Baroque opera in which he had worked and which is rarely presented these days.

probably on February 15th (although some musicologist think he might have been born on September 28th of that year) toFrancesco Cavalli, who was born on this day in 1602, to Arcangelo Corelli, born half a century later, on February 17th of 1653, and then, skipping several well-known names, to the Hungarian composer . It was Kurtág’s name that caught our eye: in five days he will turn 96! But of course it’s not the longevity that makes him special (after all, Elliott Carter lived much longer, to the age of 103): Kurtág is one of the most interesting composers of the 20th century. Here’s an interesting question to ponder: in 100 years, assuming that classical music survives that long as a genre, who would be more popular, Corelli or Kurtág? We think that Kurtág is a much more original composer, but will music lovers internalize and accept the complexities of his music (obviously this is not the case yet). As long as we ventured into the shaky grounds of comparisons, we might as well say that we think that Cavalli was more interesting than Corelli, except for the genre of the early Baroque opera in which he had worked and which is rarely presented these days.

György Kurtág (his first name is pronounced closer to Dyerd rather than George) was born on February 19th of 1926 in Lugoj, Banat. These days most of the historical Banat lies in Romania, but prior to 1918 Banat was part of the Austro-Hungarian empire; many inhabitants were Hungarian speakers. It also had a large Jewish population; Kurtág is half-Jewish. He spoke Hungarian at home and Romanian at school. As a child, he studied the piano on and off, first with his mother, then with professional teachers. After WWII, in 1946, the 20-year old Kurtág moved to Budapest and continued taking piano lessons, eventually entering the Franz Liszt Music Academy. There he met György Ligeti and they became friends for life. After the Hungarian revolution of 1956, Kurtág moved to Paris. There he studied with Olivier Messiaen and Darius Milhaud. He returned to Hungary in 1959 and stayed there for the duration of the Communist regime – the only Hungarian composer of international renown to do so (Ligeti, for example, fled to Vienna right after the failed revolution and stayed in the West for the rest of his life). At that time Kurtág became influential as a teacher. Surprisingly, he didn’t teach composition but rather interpretation: the pianists Zoltán Kocsis and András Schiff, and the first Takács String Quartet were among his pupils. Kurtág resumed traveling only after the fall of communism in 1989, moving first to Berlin (he was the composer in residence for the Berlin Philharmonic in the mid-90s), then Vienna, the Netherlands and Paris, where he worked with Boulez’s Ensemble Intercontemporain. In 2002, the Kurtágs settled in Bordeaux but in 2015 he and his wife live returned to Budapest (Kurtág’s wife Márta, a pianist, died in 2019).

In addition to Kurtág’s music already in our library, we have two more pieces to illustrate Kurtág’s art. First, a very simple and short piano piece titled ... feuilles mortes ... It’s performed by the Armenian pianist Hayk Melikyan (here). And here is a much more complex …concertante… for violin, viola and orchestra, written in 2003. It’s performed by Hiromi Kikuchi, violin, Ken Hakii, viola and the BBC Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Jukka-Pekka Saraste.Permalink

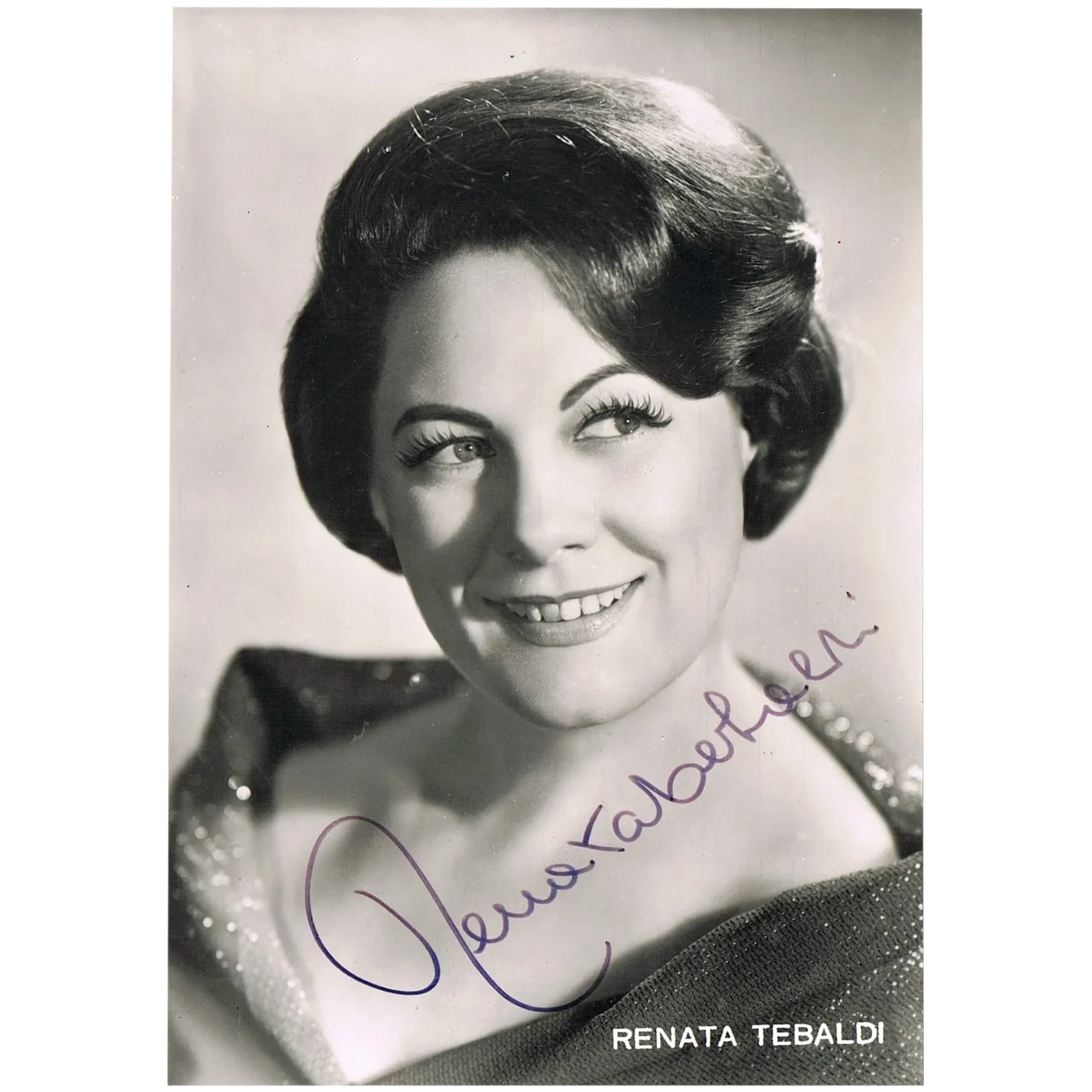

This Week in Classical Music: February 7, 2022. Renata Tebaldi. Last week we missed a very important anniversary: Renata Tebaldi was born 100 years ago! Tebaldi had one of the most beautiful voices of the century, which Toscanini called “the voice of an angel.” She was a rival of Maria Callas, who was a year younger than Tebaldi – it’s hard to imagine that two sopranos of such talent were singing contemporaneously, although Callas’s career was much shorter. It’s difficult to argue that Tebaldi’s voice was more “classical” and in many ways better, although Callas’s had an amazing emotional quality which Tebadli’s interpretations sometimes lacked. Their voices also had somewhat different timbre and range: Callas was a dramatic soprano capable of singing coloratura parties, she was especially good in the bel canto repertoire, while Tebaldi was a lyric soprano at her best in the verismo operas. They shared some roles, Tosca being one of them. Opera lovers will be forever divided between those two divas while adoring them both.

beautiful voices of the century, which Toscanini called “the voice of an angel.” She was a rival of Maria Callas, who was a year younger than Tebaldi – it’s hard to imagine that two sopranos of such talent were singing contemporaneously, although Callas’s career was much shorter. It’s difficult to argue that Tebaldi’s voice was more “classical” and in many ways better, although Callas’s had an amazing emotional quality which Tebadli’s interpretations sometimes lacked. Their voices also had somewhat different timbre and range: Callas was a dramatic soprano capable of singing coloratura parties, she was especially good in the bel canto repertoire, while Tebaldi was a lyric soprano at her best in the verismo operas. They shared some roles, Tosca being one of them. Opera lovers will be forever divided between those two divas while adoring them both.

Tebaldi was born in Pesaro on February 1st of 1922. In 1946 she took part in the opening concert at the war damaged La Scala. The conductor that evening was Arturo Toscanini, and both he and the public loved Tebaldi’s voice. She became a regular at La Scala in the post-war era. In 1950 she sang for the first time at the Covent Garden; the same year she made her debut at the San Francisco opera and then in Chicago. In 1955 she came to New York; she would appear at the Met for the following 20 years. Tebaldi performed till 1976.

As so often is the case with great artists, it’s difficult to select a recording to illustrate their art. Mimi in La Bohème was one of Tebadli’s great roles. Here she is in Si. Mi chiamano Mimi, from the 1959 recording. The Orchestra of Santa Cecilia is conducted by Tullio Serafin. And here is a scene from another opera in which Tebaldi excelled: Pace, pace mio Dio, from Verdi’s La Forza del Destino. This recording was made in 1958 in concert; Leonard Bernstein conducts The New York Philharmonic.

This week and the previous one were rich on singers’ anniversaries: last week we could’ve also celebrated Jussi Björling’s birthday, who was born on February 5th of 1911; this week there are two greats: the soprano Hildegard Behrens who excelled in the German repertoire, from Mozart to Wagner and Berg, and the incomparable Leontyne Price. Behrens was born on February 9th of 1937 and Price – on February 10th of 1927, so she will be celebrating her 95th birthday. Price deserves a full entry, which will be forthcoming. In the meantime, you may be interested to compare Pace, mio dio sung by Tebaldi, above, with Price’s 1984 recording, here.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: January 31, 2022. Schubert and more. Franz Schubert, one of the greatest composers of the 19th century, was born on this day in 1797. We love Schubert and have written about him and his work on many occasions, and here’s a bit more. Schubert’s last three piano sonatas are some of his greatest works. They were composed in 1828, practically in the last half a year of Schubert’s life, as he was dying of syphilis. Inevitably they are compared to Beethoven’s last five: pianos sonatas number 28, op. 101 through 32, op. 111. There clearly are parallels: the scope, the depth, the variety of musical material and just pure beauty. We should remember that Beethoven’s sonatas, as coherent as they are in their dramatic effect, were written during a period of five years, not in a feverish six months, as Schubert’s. Schubert’s last sonatas, although profound, are somewhat loosely structured. That was one of the reasons they were considered somewhat inferior after they were published in1838, ten years after Schubert’s death. This lack of internal structure (and, in some cases, excessive length) make these sonatas difficult to play. There are some pianists who excel in them, Alfred Brendel, Sviatoslav Richter, Claudio Arrau, Maurizio Pollini being one of the best (of course there were many more who’ve played them wonderfully). This is also the reason why some famous pianists don’t do as well: we remember Lang Lang’s performance in Chicago in 2008, which we thought was quite disastrous: our impression was that Lang Lang doesn’t quite understand what he was playing. Of course back then Lang Lang was a media darling and many classical music critics went along with it, so the reviews of the concert were mostly positive. Things have changed since then… Here is Sviatoslav Richter playing Pianos Sonata D. 958 in C minor; the recording was made in 1972. And Here is’ Alfred Brendel in the Sonata D. 959 in A major, from a 1988 recording.

have written about him and his work on many occasions, and here’s a bit more. Schubert’s last three piano sonatas are some of his greatest works. They were composed in 1828, practically in the last half a year of Schubert’s life, as he was dying of syphilis. Inevitably they are compared to Beethoven’s last five: pianos sonatas number 28, op. 101 through 32, op. 111. There clearly are parallels: the scope, the depth, the variety of musical material and just pure beauty. We should remember that Beethoven’s sonatas, as coherent as they are in their dramatic effect, were written during a period of five years, not in a feverish six months, as Schubert’s. Schubert’s last sonatas, although profound, are somewhat loosely structured. That was one of the reasons they were considered somewhat inferior after they were published in1838, ten years after Schubert’s death. This lack of internal structure (and, in some cases, excessive length) make these sonatas difficult to play. There are some pianists who excel in them, Alfred Brendel, Sviatoslav Richter, Claudio Arrau, Maurizio Pollini being one of the best (of course there were many more who’ve played them wonderfully). This is also the reason why some famous pianists don’t do as well: we remember Lang Lang’s performance in Chicago in 2008, which we thought was quite disastrous: our impression was that Lang Lang doesn’t quite understand what he was playing. Of course back then Lang Lang was a media darling and many classical music critics went along with it, so the reviews of the concert were mostly positive. Things have changed since then… Here is Sviatoslav Richter playing Pianos Sonata D. 958 in C minor; the recording was made in 1972. And Here is’ Alfred Brendel in the Sonata D. 959 in A major, from a 1988 recording.

Felix Mendelssohn was also born this week, on February 3rd of 1809. By the time of Schubert’s death, when Mendelssohn was 19, he has already written several dozen compositions, including quartets, a symphony, and the famous Midsummer Night's Dream Overture. And two great violinists, Fritz Kreisler and Jascha Heifetz were born on the same day this week, February 2nd, Kreisler in 1875 and Heifetz in 1901.

Also, the conductor Erich Leinsdorf, who was born Erich Landauer into a Jewish family in Vienna on February 4th of 1912, 110 years ago. He became Bruno Walter’s assistant at Salzburg in 1934 at the age of 22. Leinsdorf left Austria several weeks before the Anschluss, Nazi Germany’s capture of Austria, to assume the position of assistant conductor at the Metropolitan opera and stayed in the US for the rest of his life, becoming a naturalized citizen in 1942. He became the Music director of the famed Cleveland Orchestra at the age of 31 but served briefly as he was conscripted to the Army. Leinsdorf had a distinguished career: he was named the Music director of the Boston Symphony orchestra in 1962, conducted many operas and the Met and guest-conducted many major orchestras. He also made a number of highly acclaimed recordings, both symphonic and operatic. Of the latter, Un ballo in maschera, Tristan und Isolde, Die Walküre and Turandot are considered most interesting.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: January 24, 2022. Mozart and more. January 27th is Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s birthday (he was born in 1756) and a strange question comes to mind: how did Mozart escape the wrath of the woke cultural commissars? Obviously, this question would never arise under normal circumstances, but these days nothing is normal. Beethoven, the titan of European music, has been in crosshairs of the woke musicologists for at least the last two years, becoming a symbol for the “overrated dead white men.” But if you think of it, it could as easily have been Mozart: Beethoven, after all, had rather dark skin (there was even silly talk that he could’ve been of African descent), whereas Mozart’s skin, judging by several authentic portraits, was milky-white. And Beethoven had a handicap – he was practically deaf half of his life, which in the era of intersectionality and disability studies could’ve earned him some points with the woke crowd. Mozart, on the other hand, even though often poor, was happily married (Beethoven never was), loved women and partying and was prone to making silly scatological jokes. One would think that of the two, the woke would go after Mozart, but no – since their insane minds work in mysterious ways. The only thing we can say is that we’re happy for Wolfgang. That said, here, to celebrate, is Mozart’s Symphony no. 38, "Prague," performed live in 2017 by the Chamber Orchestra of Europe under the direction of Bernard Haitink.

Mozart escape the wrath of the woke cultural commissars? Obviously, this question would never arise under normal circumstances, but these days nothing is normal. Beethoven, the titan of European music, has been in crosshairs of the woke musicologists for at least the last two years, becoming a symbol for the “overrated dead white men.” But if you think of it, it could as easily have been Mozart: Beethoven, after all, had rather dark skin (there was even silly talk that he could’ve been of African descent), whereas Mozart’s skin, judging by several authentic portraits, was milky-white. And Beethoven had a handicap – he was practically deaf half of his life, which in the era of intersectionality and disability studies could’ve earned him some points with the woke crowd. Mozart, on the other hand, even though often poor, was happily married (Beethoven never was), loved women and partying and was prone to making silly scatological jokes. One would think that of the two, the woke would go after Mozart, but no – since their insane minds work in mysterious ways. The only thing we can say is that we’re happy for Wolfgang. That said, here, to celebrate, is Mozart’s Symphony no. 38, "Prague," performed live in 2017 by the Chamber Orchestra of Europe under the direction of Bernard Haitink.

Several very interesting composers were also born this week: Witold Lutoslawski, one of the greatest Polish composers of the 20th century, on January 25th of 1913. Luigi Nono, the Italian, was born 11 years later, on January 29th of 1924; Nono was one of the most influential modernist composers of the century. 20 years after Nono the British religious minimalist John Tavener was born on January 28th of 1944. Here’s Lutoslawski’s Symphony no. 3, performed by the Berlin Philharmonic under the direction of the composer.

Lutoslawski, even though he regularly conducted his own music, was much better known as a composer. Wilhelm Fürtwangler, on the other hand, even though he composed several symphonies, chamber music and several choral works, is famous as a conductor, one of the greatest ever, and practically unknown as composer. Fürtwangler was born on January 25th of 1886 in Schöneberg, Berlin. A great musician, he was politically controversial, as were many German musicians who lived during the Nazi era. We wrote about the first half of his life here (will try to complete his story sooner rather than later). Here is a live recording of Bruckner’s Symphony no. 9, made live in Beethovensaal, Berlin, on October 7th of 1944 (Beethovensaal was one of the Philharmonic’s temporary homes after the original one, Alte Philharmonie, was completed destroyed after the Allied bombing raid on January 30th of 1944).Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: January 17, 2022. Hofmann and Elman. A whole bunch of composers were born this week, but none of them are of the very first rank. Johann Hermann Schein, our recent “discovery,” who was born on January 20th of 1586, but he was outshone by his good friend Heinrich Schütz. Ernest Chausson, born on January 20th of 1855 and mostly known for his Poème for violin and orchestra, may have developed into a more interesting composer had he not died at the age of 44 after hitting a brick wall while riding a bicycle. Muzio Clementi probably isn’t much liked by anybody who has studied piano as a kid for his rather unimaginative, simple Sonatinas that were part of the obligatory school repertory. Clementi, the Italian who spend much of his life in England, had a very interesting life (and also wrote some pretty good music). We wrote an entry about him several years ago (here); Clementi was born on January 23rd of 1752. Also this week, two Frenchmen, two Henris: Duparc on January 21st of 1848 and Dutilleux, on January 22nd of 1916; the Russian composer Alexander Tcherepnin, on January 20th of 1899; and the American Walter Piston, on January 20th of 1894.

1848 and Dutilleux, on January 22nd of 1916; the Russian composer Alexander Tcherepnin, on January 20th of 1899; and the American Walter Piston, on January 20th of 1894.

On the other hand, two of the most interesting instrumentalists of the 20th century, the pianist Josef Hofmann and the violinist Mischa Elman were also born this week, both in the former Russian Empyre: Hofmann in Krakow, now Poland, on January 20th of 1876 and Elman in Talnoye, a small town south of Kiev in the modern-day Ukraine, on the same day 15 years later, in 1891. Hofmann, a prodigy, toured Europe at the age of seven. At the age of eleven he played at the Metropolitan Opera in New York and created a furor. In 1892 he went to Berlin to study and eventually became the only private student of Anton Rubinstein, the great Russian pianist and composer. In 1894 Hoffman renewed his performing career, playing around the world to enormous success (that was also the year Anton Rubinstein died). Hofmann was considered the supreme virtuoso of his time. Rachmaninov dedicated his Third Piano Concerto, probably the most difficult of the four, to Hofmann (as it happens, Hofmann never played it). Hofmann moved to the US during the First World War and became an American citizen in 1926. In 1924 he became director of the recently founded Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. In the late 1930s Hofmann became an alcoholic, and his musicianship deteriorated rapidly. He was forced to leave the Curtis in 1938, and played, disastrously, his last public concert at the Carnegie Hall in 1946. Hofmann, who was very good at math as a kid, was an inventor and had 70 patents to his name.

Here, from 1937 Golden Jubilee concert at the old Metropolitan Opera house is Josef Hofmann playing Chopin’s Ballade no. 1 in G minor, Op. 23, here – Chopin’s Waltz op. 42, no. 5 in A flat major from the same concert.

We’ll have to write about Mischa Elman another time, but here is one of the pieces he liked to play as an encore: Schubert’s Ave Maria. And here is Humoresque by Dvorak. Joseph Seiger is on the piano.Permalink

We’ll use this quiet week to “discover” Antoine Brumel, a French composer who was born sometime around 1460 probably in Brunelles, not far from Chartres. His is one of a few French composers who were part of the Franco-Flemish (Burgundian) school, the rest of them being mostly Flemish, like Guillaume Dufay, Gilles Binchois or Johannes Ockeghem. As usual for composers of the 15th century, we don’t know much about his life. Here’s what we do know: he sang at the famous Chartres Cathedral, then moved to Geneva where he stayed for several years, became a canon and served in Laon, and then became the choirmaster at the Notre Dame de Paris. In 1506 he moved to Italy to the court of Alfonso I d'Este in Ferrara where he assumed the duties of the maestro di cappella, replacing Jacob Obrecht who had died of the plague there the previous year. He stayed in Ferrara till 1510, when the chapel was disbanded. He lived in Italy for another two years and died, probably in Mantua, sometime around 1512.

We’ll use this quiet week to “discover” Antoine Brumel, a French composer who was born sometime around 1460 probably in Brunelles, not far from Chartres. His is one of a few French composers who were part of the Franco-Flemish (Burgundian) school, the rest of them being mostly Flemish, like Guillaume Dufay, Gilles Binchois or Johannes Ockeghem. As usual for composers of the 15th century, we don’t know much about his life. Here’s what we do know: he sang at the famous Chartres Cathedral, then moved to Geneva where he stayed for several years, became a canon and served in Laon, and then became the choirmaster at the Notre Dame de Paris. In 1506 he moved to Italy to the court of Alfonso I d'Este in Ferrara where he assumed the duties of the maestro di cappella, replacing Jacob Obrecht who had died of the plague there the previous year. He stayed in Ferrara till 1510, when the chapel was disbanded. He lived in Italy for another two years and died, probably in Mantua, sometime around 1512.

This Week in Classical Music: January 10, 2022. Antoine Brumel. This is a surprisingly uneventful week, with the exception of Morton Feldman’s anniversary (he was born on January 12th of 1926). We don’t think that we should assault our listeners with his music: we find some of it interesting but exceedingly long (his String quartet no. 2 runs for about six hours; For Philip Guston – a piece for flute, percussion and piano – takes about five hours to perform, while Triadic Memories for the piano could be dispatched in a mere 90 minutes). On second thought, here is a four-minute piece called Madame Press Died Last Week At Ninety, dedicated to Feldman’s childhood piano teacher. It’s whimsical, somewhat unusual for Feldman and quite innocuous. John Adams conducts the Orchestra of St. Lukes.

Brumel wrote mostly sacred music: a number of masses and motets. Here, for example, is the section Gloria from his Mass Et ecce terrae motus for 12 voices, and here – Agnus Dei from the same mass. The Tallis Scholars are conducted by Peter Philips. And here is Brumel’s beautiful antiphon (short chant) Sicut lilium. It’s performed by the ensemble I buoni antichi under the direction of Coen Vermeeren.Permalink