Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: April 24, 2023. Benedetto Pamphili. Occasionally we write about historical figures that, while not directly involved in composing or making music, greatly affected musical culture, for example, through their patronage, as librettists, or as music producers. Queen Christina is probably the most famous example of a patron. In a very different way, Pietro Metastasio, who wrote libretti to operas by Vinci, Caldara, Hasse, and many other opera seria composers, was also very influential. And then there was Lorenzo da Ponte: we know him as the librettist to Mozart’s Don Giovanni, Così fan tutte, and The Marriage of Figaro, but he also wrote libretti for 25 other operas by 11 composers, Antonio Salieri among them. The famous impresario Sol Hurok is an example of a powerful producer who shaped several musical careers.

affected musical culture, for example, through their patronage, as librettists, or as music producers. Queen Christina is probably the most famous example of a patron. In a very different way, Pietro Metastasio, who wrote libretti to operas by Vinci, Caldara, Hasse, and many other opera seria composers, was also very influential. And then there was Lorenzo da Ponte: we know him as the librettist to Mozart’s Don Giovanni, Così fan tutte, and The Marriage of Figaro, but he also wrote libretti for 25 other operas by 11 composers, Antonio Salieri among them. The famous impresario Sol Hurok is an example of a powerful producer who shaped several musical careers.

Cardinal Benedetto Pamphili, whom we are celebrating today, was prominent in all three areas: he was an important benefactor, he wrote several libretti, and he staged many productions, some of which were premiers. Benedetto Pamphili was born in Rome on April 25th of 1653 into a prominent family whose name in Italian is often spelled Pamphilj, the ending “j” indicating a long “e” sound. Benedetto’s great-grandfather was Pope Innocent X, whose portrait you can see below. (The portrait, one of the greatest ever created, was painted by Diego Velázquez. It now hangs in a separate room in Galleria Doria Pamphilj; it alone is worth the price of the ticket. Read more about it here). Benedetto’s parents were Cardinal Camillo Pamphilj and Olimpia Aldobrandini, from a no less powerful Aldobrandini family. In order to marry Olimpia, Camillo had to renounce his cardinalship. The Palazzo Doria Pamphilj, which houses the gallery, was part of Olimpia’s dowry; prior to her marriage, it was called Palazzo Aldobrandini (the original Palazzo Pamphilj is on Piazza Navona and is now owned by the Brazilian embassy).

portrait, one of the greatest ever created, was painted by Diego Velázquez. It now hangs in a separate room in Galleria Doria Pamphilj; it alone is worth the price of the ticket. Read more about it here). Benedetto’s parents were Cardinal Camillo Pamphilj and Olimpia Aldobrandini, from a no less powerful Aldobrandini family. In order to marry Olimpia, Camillo had to renounce his cardinalship. The Palazzo Doria Pamphilj, which houses the gallery, was part of Olimpia’s dowry; prior to her marriage, it was called Palazzo Aldobrandini (the original Palazzo Pamphilj is on Piazza Navona and is now owned by the Brazilian embassy).

Benedetto, who inherited a fortune, also had a considerable income from numerous ecclesiastical positions he was granted by Pope Innocent XI. He spent much of it on art and patronage. Benedetto was a gifted writer and was admitted into two prestigious Academies: Accademia degli Umoristi, a literary society whose members were some of the best writers of the time (despite its name the Academy wasn’t necessarily dedicated to humoristic arts), and Accademia dell'Arcadia, about which we wrote an entry some time ago. As music was Benedetto’s favorite art, he applied his literary talents to writing libretti. Operas were prohibited in Rome by Pope Clement XI in 1703, so most of these libretti were for oratorios and cantatas, which temporarily replaced operas as accepted genres (texts for 88 cantatas are extant). A few of Benedetto’s operas were staged before the prohibition went into effect, for example, Alessandro Scarlatti’s La santa Dimna, presented in Palazzo Doria Pamphilj in 1687.

Benedetto employed several maestro di musica, among them Lulier and Cesarini. Arcangelo Corelli played in his orchestra and was handsomely rewarded for it. Bernardo Pasquini, a composer of operas and oratorios, was also supported by Benedetto, as was Giovanni Bononcini. His most famous charge was Handel during the young composer’s stay in Rome. They became friends and Handel dedicated several cantatas and oratorios to his patron.

Benedetto held weekly musical events in his palace, as did some other powererful cardinals, like Pietro Ottoboni and Carlo Colonna; he also sponsored productions in other theaters. What is interesting about these productions is the size of the orchestras they employed. We are used to the staging of Baroque operas supported by scaled-down groups, often consisting of just several players: a couple of violins, a viola da gamba, a theorbo, and a harpsichord. According to Lowell Lindgren, Benedetto employed 32 musicians in Scarlatti's Il trionfo della gratia and 60 for Lulier's S Maria Maddalena de' pazzi. Maybe the musical accompaniment of Baroque operas doesn’t have to sound so thin after all.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: April 17, 2023. Schillings and the problem of evil. In his “little tragedy” Mozart and Salieri, the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin made a profound, if not necessarily true statement: “Genius and villainy are two things incompatible.” We’d like to believe it to be true, and in some higher sense it should be true, but we know that history is full of villainous geniuses. As far as music is concerned, Richard Wagner’s name is the first to come to mind. He was a vile antisemite and made statements that today are difficult to comprehend. One thing we’d like to make clear about Wagner is that in no way was he responsible for the atrocities committed by the Nazis, though much of them were accompanied by his music. Wagner’s music was favored by Hitler, but the Führer also loved Bruckner and Beethoven. Wagner’s place in the Nazi culture was unique, partly because of the Bayreuth Festival, run by the antisemitic Winifred Wagner, the wife of Richard’s son Siegfried and Hitler’s dear friend, but in no way does this make Wagner, as terrible a person as he was, an accomplice. Then there was Carlo Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa and Count of Conza, who murdered his wife and Fabrizio Carafa, Duke of Andria, after finding them in flagrante. Alessandro Stradella, a wonderful composer, embezzled money from the Catholic church, seduced and abandoned many women, and was killed by three assassins hired by a nobleman who found out that Stradella had become a lover of his mistress (or, in another version of the story, the nobleman’s sister). One person we find especially fascinating is the painter of genius, Caravaggio, who murdered several people, maimed many more, belonged to a gang, was arrested on many occasions, and had fled from justice for half of his life. We tend not to remember these things when we look at his pictures, some of the most profound ever created.

necessarily true statement: “Genius and villainy are two things incompatible.” We’d like to believe it to be true, and in some higher sense it should be true, but we know that history is full of villainous geniuses. As far as music is concerned, Richard Wagner’s name is the first to come to mind. He was a vile antisemite and made statements that today are difficult to comprehend. One thing we’d like to make clear about Wagner is that in no way was he responsible for the atrocities committed by the Nazis, though much of them were accompanied by his music. Wagner’s music was favored by Hitler, but the Führer also loved Bruckner and Beethoven. Wagner’s place in the Nazi culture was unique, partly because of the Bayreuth Festival, run by the antisemitic Winifred Wagner, the wife of Richard’s son Siegfried and Hitler’s dear friend, but in no way does this make Wagner, as terrible a person as he was, an accomplice. Then there was Carlo Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa and Count of Conza, who murdered his wife and Fabrizio Carafa, Duke of Andria, after finding them in flagrante. Alessandro Stradella, a wonderful composer, embezzled money from the Catholic church, seduced and abandoned many women, and was killed by three assassins hired by a nobleman who found out that Stradella had become a lover of his mistress (or, in another version of the story, the nobleman’s sister). One person we find especially fascinating is the painter of genius, Caravaggio, who murdered several people, maimed many more, belonged to a gang, was arrested on many occasions, and had fled from justice for half of his life. We tend not to remember these things when we look at his pictures, some of the most profound ever created.

The musician whom we decided to write about this week never had the talent of the artists just mentioned, but neither were his sins as deep; nonetheless, his story, which is much closer to our time, seems to be more relevant. His name was Max Schillings, he was born on April 19th of 1868 in Düren, the Kingdom of Prussia. He studied the piano and the violin in Bonn and later entered the University of Munich, where he took courses in law, philosophy, and literature. While in Munich, he met Richard Strauss who became his friend for life. In 1892 Schillings was appointed assistant stage conductor at Bayreuth; in 1903 he was made professor in Munich (Wilhelm Furtwängler was one of his students). In 1908 he became the assistant to the Director of the Royal Theater in Stuttgart, the city’s main opera house, where he staged several premieres, including Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos; later he also conducted Strauss’s Salome and Elektra. By then he had composed several operas, most of them unsuccessful imitations of Wagner. Then, in 1915, he had a breakthrough with his opera Mona Lisa, which became the most often staged opera of the time. In 1918 Schillings succeeded Richard Strauss as the Intendant of the State Opera in Berlin (we know it as Staatsoper Unter den Linden; Barenboim lead it for years). He then spent several years outside of Germany, conducting and staging operas in Europe and the US. Upon his return in 1932, he was appointed President of the Prussian Academy of the Arts.

Schillings was a rabid antisemite, a nationalist and an opponent of the Weimar Republic. As soon as he became the President of the Academy, he fired some of the most talented members, among them Heinrich and Thomas Mann; Alfred Döblin, the author of Berlin Alexanderplatz; the composer Franz Werfel. He terminated Arnold Schoenberg’s contract and sent Franz Schreker into retirement. God only knows what else he would have done had he lived through the Nazi period, but he died on July 24th of 1933, four months after the Enabling Act gave Hitler dictatorial powers. We don’t want to keep Schillings’s music in our library, but you can find Mona Lisa on YouTube.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: April 10, 2023. Pletnev and Caballé. Mikhail Pletnev is a wonderful pianist and an interesting conductor. He was born on April 14th of 1957 in the northern Russian city of Arkhangelsk. In 1978, when he was 21, Pletnev won the first prize at the sixth Tchaikovsky competition. That brought him international recognition and his career took off. He debuted in the US the following year and since then has performed in all major venues and played concerts with the best conductors, Claudio Abbado, Bernard Haitink, Lorin Mazel, and Zubin Mehta among them. As a pianist, Pletnev has a special affinity with Rachmaninov and is acknowledged as one of the best performers of his music. In 1990, Pletnev founded the Russian National Orchestra (RNO), the first non-governmental orchestra in the country since 1917, and developed it into one of the best orchestras in Russia. The NRO recordings of Tchaikovsky’s symphonies are especially good. Everything changed in 2022 with the Russian aggression against Ukraine. Pletnev’s reaction was both negative and direct. In an interview, he said: “Who starts the wars? Only stupid politicians. Not a single normal person likes the war. But the politicians use propaganda and manipulation, and they use them for their own benefit, not ours.” Of course, in a country with only one politician, Mr. Putin, this couldn’t be tolerated. First, the Russian government fired RNO’s executive director, a Pletnev supporter, and then practically banned Pletnev from conducting his own orchestra. Since then, Pletnev has created another ensemble he calls the Rachmaninoff International Orchestra. Among its members are musicians from Eastern and Western Europe, and 18 former members of the RNO.

northern Russian city of Arkhangelsk. In 1978, when he was 21, Pletnev won the first prize at the sixth Tchaikovsky competition. That brought him international recognition and his career took off. He debuted in the US the following year and since then has performed in all major venues and played concerts with the best conductors, Claudio Abbado, Bernard Haitink, Lorin Mazel, and Zubin Mehta among them. As a pianist, Pletnev has a special affinity with Rachmaninov and is acknowledged as one of the best performers of his music. In 1990, Pletnev founded the Russian National Orchestra (RNO), the first non-governmental orchestra in the country since 1917, and developed it into one of the best orchestras in Russia. The NRO recordings of Tchaikovsky’s symphonies are especially good. Everything changed in 2022 with the Russian aggression against Ukraine. Pletnev’s reaction was both negative and direct. In an interview, he said: “Who starts the wars? Only stupid politicians. Not a single normal person likes the war. But the politicians use propaganda and manipulation, and they use them for their own benefit, not ours.” Of course, in a country with only one politician, Mr. Putin, this couldn’t be tolerated. First, the Russian government fired RNO’s executive director, a Pletnev supporter, and then practically banned Pletnev from conducting his own orchestra. Since then, Pletnev has created another ensemble he calls the Rachmaninoff International Orchestra. Among its members are musicians from Eastern and Western Europe, and 18 former members of the RNO.

Here are several piano recordings by Mikhail Pletnev. First, Rachmaninov’s Corelli Variations, recorded live in Moscow in 2001 (here). Then, another live recording, made in Luxemburg in 2015: a rather idiosyncratic interpretation of Chopin’s Nocturne in C-sharp minor op. posth. (here). And lastly, from Carnegie Hall, also live, the year 2000 recording of Chopin’s Scherzo no. 1 (here).

The great Spanish soprano Montserrat Caballé, “La Superba,” was born on April 12th of 1933 in Barcelona. Here she sings the aria Donde Lieta Usci from Puccini’s La Bohème. Charles Mackerras conducts the London Symphony Orchestra.

PermalinkThis Week in Classical Music: April 3, 2023. Two Italian Tenors. Only one of these singers has an anniversary this week, and that’s Franco Corelli, who was born on April 9th of 1921 in.jpg) Ancona. Another tenor is Beniamino Gigli, whose name we mentioned several weeks ago when we were celebrating the birthday of the great Enrico Caruso. We promised then to write about Gigli, probably second only to Caruso among tenors of the first half of the 20th century. Gigli was born on March 20th of 1890, but with Bach and Rachmaninov’s 150th anniversaries intervening, this is the earliest we could get to Gigli.

Ancona. Another tenor is Beniamino Gigli, whose name we mentioned several weeks ago when we were celebrating the birthday of the great Enrico Caruso. We promised then to write about Gigli, probably second only to Caruso among tenors of the first half of the 20th century. Gigli was born on March 20th of 1890, but with Bach and Rachmaninov’s 150th anniversaries intervening, this is the earliest we could get to Gigli.

Forty years separate Gigli from Corelli; that gap affected their legacies in many ways, but two of them are very important: one is technology, the other – politics. Gigli made a large number of records, but the recording technology of his time was rather poor, and the sound quality of his shellac records cannot compare with the ones made by Corelli. Subsequently, we rarely can hear the tone quality for which Gigli was famous. And politics is the second important factor: Gigli lived during the fascist years of Mussolini’s reign, and as was the case with many German, Soviet, and Italian musicians of the time, he compromised himself politically and ethically.

Beniamino Gigli was born in Recanati, a small town not far from Ancona on the Adriatic side of Italy. In 1914 he won a competition in Parma, and later that year made a successful début in Ponchielli’s La Gioconda. His career took off almost immediately, and he was invited to sing in all major opera theaters of Italy, from San Carlo in Naples to La Scala in Milan. In 1917 he sang in Spain and in 1920 made a highly successful debut in New York at the Met. He stayed in the US for the next 12 years, becoming, after Caruso’s death in 1921, the Met’s most popular tenor, even though the opera’s roster also included such singers as Giacomo Lauri-Volpi and Giovanni Martinelli. Even though the public called Gigli “Caruso Secondo,” the comparison is not fair: Caruso’s voice was bigger and darker than Gigli’s, whereas Gigli’s was “sweeter” and probably naturally more beautiful. In 1932, after refusing a pay cut, Gigli left the Met and returned to Italy. He became Mussolini’s favorite singer, which in itself, of course, is not a sin. Unfortunately, Gigli went much further: in 1937 he recorded the official hymn of the Italian fascist party, Giovinezza; in 1942 he wrote a book, Confidenze, in which he praised fascism. He valued his “friendship with Hitler, Goering and Goebbels. In 1944, he collaborated with the Germans after they occupied Rome. Were he in Germany at the end of the war, he would probably had been banned for years as a collaborator, but in Italy, he was forgiven almost immediately. Not everybody forgot his past, though: he wasn’t let into the US till 1955. That didn’t prevent Gigli from singing in Italy, Europe and South America.

Gigli’s recordings don’t do justice to his honeyed tone but we have two samples that seem to better reflect his voice. Here, from 1943, is his Vesti la giubba, from Leoncavallo’s I Pagliacci (it’s a live recording and we had to cut down part of the prolonged ovation). And here, from 1949, is Nessun dorma, from Puccin’s Turandot.

Gigli was one of Franco Corelli’s favorite singers; mostly self-taught, he learned to sing by listening to the recordings of Caruso, Lauri-Volpi and Gigli. Here’s Corelli’s rendition of Nessun dorma. Two years ago we celebrated Corelli’s 100th anniversary, you can read more about this great singer here.

PermalinkThis Week in Classical Music: March 27, 2023. Rachmaninov 150. One day of this week is very special: April 1st marks the 150th anniversary of the great Russian composer, pianist, and conductor, Sergei Rachmaninov (some outlets were celebrating his birthday on the 20th of March, as that was his birthdate according to the old Russian Julian calendar, but this is like observing the Russian Revolution on October 25th, rather than the conventional November 7th). We’re not going to trace Rachmaninov’s life; suffice it to say that it was divided into two irreconcilable parts, one, from his birth till the Russian Revolution, and then, from 1918, emigration and life in the United States. In terms of his creative output, these two parts are incomparable. The vast majority of his compositions were created while Rachmaninov lived in Russia: his piano pieces, such as the Études-Tableaux and the Preludes, the first three Piano concertos, two symphonies and Isle of the Dead, the Second piano sonata (the first one was a juvenile piece), the early operas, most of his songs, the choral works, such as The Bells and the All-Night Vigil – all of these were written in Russia. In America Rachmaninov had to earn his living by playing piano and conducting, with very little time left for composing. All he wrote while in America were (not counting several miscellaneous pieces) a not-very-successful Piano Concerto no. 4, Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Symphony no. 3, Variations on a Theme of Corelli, and Symphonic Dances. We’ve always wondered if one could explain such a tremendous disparity just by Rachmaninov’s need to earn money by performing. We suspect there was more to it, but this is not the place to address this issue.

conductor, Sergei Rachmaninov (some outlets were celebrating his birthday on the 20th of March, as that was his birthdate according to the old Russian Julian calendar, but this is like observing the Russian Revolution on October 25th, rather than the conventional November 7th). We’re not going to trace Rachmaninov’s life; suffice it to say that it was divided into two irreconcilable parts, one, from his birth till the Russian Revolution, and then, from 1918, emigration and life in the United States. In terms of his creative output, these two parts are incomparable. The vast majority of his compositions were created while Rachmaninov lived in Russia: his piano pieces, such as the Études-Tableaux and the Preludes, the first three Piano concertos, two symphonies and Isle of the Dead, the Second piano sonata (the first one was a juvenile piece), the early operas, most of his songs, the choral works, such as The Bells and the All-Night Vigil – all of these were written in Russia. In America Rachmaninov had to earn his living by playing piano and conducting, with very little time left for composing. All he wrote while in America were (not counting several miscellaneous pieces) a not-very-successful Piano Concerto no. 4, Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Symphony no. 3, Variations on a Theme of Corelli, and Symphonic Dances. We’ve always wondered if one could explain such a tremendous disparity just by Rachmaninov’s need to earn money by performing. We suspect there was more to it, but this is not the place to address this issue.

That Rachmaninov was one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century is accepted by practically everybody. But what about his compositions? He’s one of the most popular composers ever, if one judges by the number of his pieces being performed and broadcasted, the Piano concertos nos. 2 and 3 and Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini in particular. But was he a great composer? Here opinions differ. Clearly, he wasn’t an innovator, but not all great composers were: we recently talked about Bach, whose music was considered outdated by many of his contemporaries. Eric Blom, a famous music critic and the editor of the 5th edition of Grove's Dictionary of Music, was one of the skeptics. He wrote that the composer “did not have the individuality of Taneyev or Medtner. Technically he was highly gifted, but also severely limited. His music is ... monotonous in texture ... The enormous popular success some few of Rakhmaninov's works had in his lifetime is not likely to last, and musicians never regarded it with much favour.” This seems to be both wrong and unfair, and Harold Schonberg, the chief music critic of the New York Times, responded (in his book on great composers) in kind: “It is one of the most outrageously snobbish and even stupid statements ever to be found in a work that is supposed to be an objective reference.” We have to confess that sometimes, listening to somewhat shallow, formulaic passages that appear quite often in many of Rachmaninov’s pieces, we have our doubts. But that’s not the way to judge any creative artist: it should be done by what he did best, and Rachmaninov did write brilliant music. That’s what will keep him in the pantheon of composers of the first half of the 20th century.

Let’s listen to some music. First, Sviatoslav Richter plays two of Rachmaninov’s Etudes-Tableaux op.33: no. 5 and no. 6, but from 1911. And here Richter again, in Prelude no. 10, from op. 32, composed a year earlier, in 1910. And finally, a sample of Rachmaninov’s late symphonic work: from 1940, his Symphonic Dances. Vladimir Ashkenazy leads the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra.Permalink

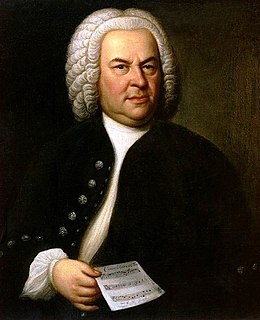

This Week in Classical Music: March 20, 2023. Bach and Four Pianists. Johann Sebastian Bach was born on March 21st of 1685 in Eisenach. Four pianists were also born this week; we’ll present them briefly and then have them play several of Bach’s works. A word on dating Bach’s compositions: even though we know a lot about his life, the dating of his output is very approximate, so sometimes it’s not clear where Bach was when he wrote some of the pieces. Different sources often provide different dates and estimate ranges.

present them briefly and then have them play several of Bach’s works. A word on dating Bach’s compositions: even though we know a lot about his life, the dating of his output is very approximate, so sometimes it’s not clear where Bach was when he wrote some of the pieces. Different sources often provide different dates and estimate ranges.

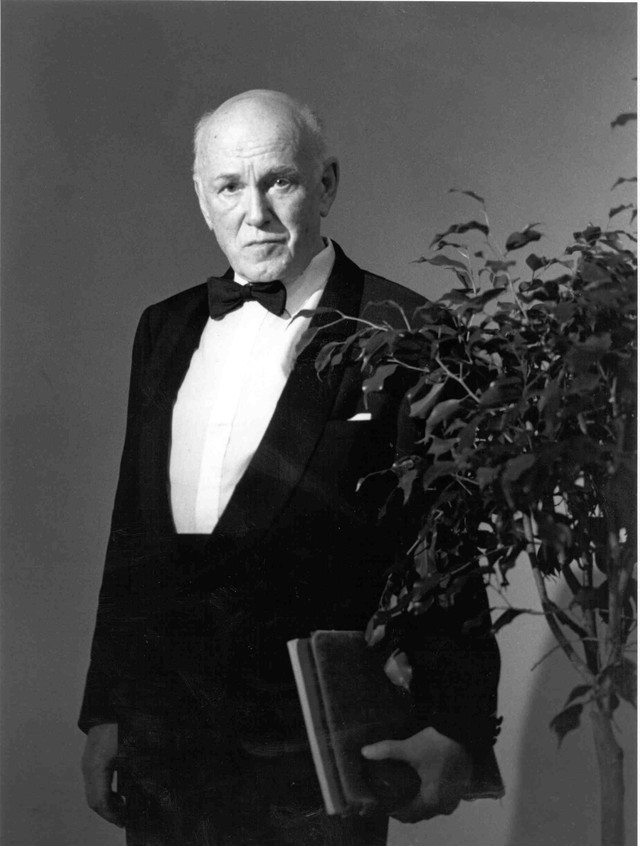

Our pianists are: Sviatoslav Richter, born on March 20th of 1915 in Zhytomyr, then in the Russian Empire, now a city in independent Ukraine. Richter is acknowledged by many as one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century. His repertoire was enormous, he said that he could play eighty different programs, not counting chamber pieces. He continued adding to it even in his 70s.

pieces. He continued adding to it even in his 70s.

Egon Petri, a German pianist of Dutch descent, was born on March 23rd of 1881 in Hanover. He was the favorite pupil and associate of Ferruccio Busoni. Petri had an illustrious international career and in 1923 became the first foreign pianist to perform in the Soviet Union. Like his teacher, much of Petri’s repertoire was concentrated on Bach, and like him, he became a famous pedagogue.

The American pianist Byron Janis will turn 95 on March 24th. He was born in McKeesport, PA into a Jewish family (the original family name was Yankelevitch). As a child, he studied with Josef and Rosina Lhévinne in New York. Vladimir Horowitz was in the audience when Janis, age 16, played Rachmaninov’s 2nd Piano Concerto and immediately took him as his first pupil. In 1960 Janis had a tremendously successful tour of the Soviet Union, just two years after Van Cliburn’s win of the First Tchaikovsky competition. Janis’s career was cut short in 1973 when he developed arthritis in both hands.

Wilhelm Backhaus, one of the most interesting German pianists of the 20th century, was born on March 26th of 1884 in Leipzig. An early protégé of Arthur Nikisch, he studied for a year with Eugene d’Albert but was mostly self-taught. In 1900, Backhaus toured England, and four years later he became a professor of music in Manchester. In 1912-1913 he toured the US, the first of his many highly successful tours of the country. In 1931 he became a Swiss citizen. His technique was legendary, and he maintained it well into his 80s. Backhaus was compromised by his association with the Nazis after their takeover in 1933. We’ll address this chapter of his life later.

So now to some Bach, as performed by our pianists. Here is an early (1948-1952) Sviatoslav Richter recording of Fantasia and Fugue in A minor, BWV 944. Bach wrote it sometime between 1707-1713/1714 when he was most likely in Weimar, where he was an organist and Konzertmeister at the ducal court.

And here is a much later work, Prelude, Fugue and Allegro in E-Flat Major, BWV 998, from 1740-1745, when Back was Thomaskantor in Leipzig. It’s performed by Egon Petri.

Here, 19-year-old Byron Janis plays Prelude and Fugue in A minor, BWV 543 as arranged by Liszt. The dating of this piece is all over the place: Grove Music says “after 1715,” Wikipedia – after 1730.

And finally, Wilhelm Backhaus plays the English Suite No. 6 in D minor, BWV 811 (here), composed sometime between 1720 and 1725. This is a bit problematic because in 1720 Bach was living in Köthen, serving as the Kapellmeister to the Prince of Anhalt-Köthen, while in 1725 he was already in Leipzig. Permalink